This is an excerpt from The 2018 BCG Local Dynamos: Emerging-Market Companies Up Their Game .

Emerging markets are dynamic and hotly contested. Some of the most successful players in these markets are savvy local companies, operators that have built business models and capabilities to capitalize on the powerful forces shaping their home countries. To shed light on some of the biggest success stories, we have compiled a list of 50 companies, a group we dub local dynamos. Emerging-Market Companies Up Their Game . They frequently outperform both local state-owned companies, which have built-in advantages, and large multinationals.

The 2018 BCG Local Dynamos

The 2018 BCG Local Dynamos

- Emerging-Market Companies Up Their Game

- How the Local Dynamos Win at Home

- What’s Powering Local Dynamos: The Infographic

So how, exactly, do local dynamos win there, particularly against large rivals with greater economies of scale and resources?

Dynamos certainly have some institutional advantages, including deep insight regarding the regulatory and political landscapes within their countries and how to navigate them to their advantage. Because nonlocal companies cannot easily replicate those advantages, we examined other factors that distinguish the dynamos—traits that both new entrants and existing players in emerging markets can emulate or adapt.

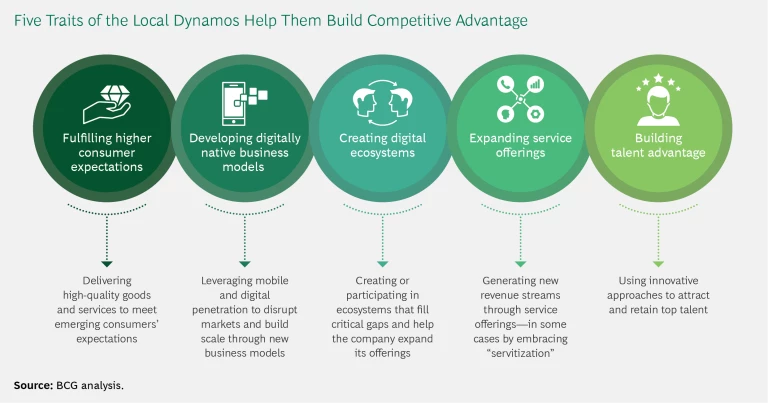

On the basis of our study of the 50 local dynamos on this year’s list, we have identified five traits that set up these companies for success. (See the exhibit.) The traits reflect the ability of local dynamos to assess and adapt to the competitive environment. That means not only capitalizing on the trends within their markets but also responding to changing global dynamics. After all, although these companies are focused on their domestic markets, the shifts that are transforming global competition still have significant implications for them. (See “What the New Globalization Means for Local Dynamos.”)

What the New Globalization Means for Local Dynamos

What the New Globalization Means for Local Dynamos

There are powerful new dynamics in globalization—and each has significant implications for local dynamos.

The first new dynamic is the growing wave of economic nationalism. This surge can be seen most readily in mature markets, such as the UK (with Brexit) and the US (with the recent moves on steel and aluminum tariffs). Meanwhile, governments in a number of emerging markets—including China, India, Indonesia, and Nigeria—have instituted local content requirement rules to foster the development of domestic industries. At the same time, there has been a rise in state capitalism, under which sovereign wealth funds and state sponsorship are used to support local companies. For local companies in emerging markets, such shifts can lead to greater consumer enthusiasm for locally made products as well as new sources of capital. In fact, there are signs that support for local brands is building: from 2007 to 2015, Chinese consumers increasingly preferred local brands over international ones in such categories as home appliances, digital, fashion and apparel, and cosmetics.

The second new dynamic comprises the ways in which digital technologies are remaking global competition. Advanced digital manufacturing systems allow companies to operate smaller, more flexible plants closer to end users. In addition, companies can use digital platforms to offer new, cross-border services in a way that was impossible in the past—think health and wellness monitoring with devices such as Fitbit, entertainment services through Netflix or Spotify, and remote plant equipment maintenance and servicing.

Such digital advances can cut both ways for local dynamos. Digital technologies that facilitate customer access, lower transaction costs, and enable local distribution capabilities, for example, erode the competitive advantage that has typically been built through scale. This helps level the playing field for smaller local companies that compete against MNCs. At the same time, however, digital platforms can allow large multinationals to penetrate emerging markets with limited upfront investment—a potential threat to local dynamos. As a result, local dynamos must think globally when assessing how digital changes impact their business, including understanding where global scale versus local operations create competitive advantage, how they should adjust their offerings to meet rising global quality standards, and where they should build new connections with potential partners.

As a result of these shifting global dynamics, companies are adopting new business models to compete. Through “servitization,” a company can charge for the use of a product rather than for the product itself. Personalization allows companies to curate their offerings to suit customer-specific needs and tastes. And the growth of powerful digital ecosystems helps companies meet multiple customer needs by creating a one-stop shop involving a collaborative network of partners working on a common platform.

Across all these developments, the common theme is the dramatic shift toward focusing on customer needs and the delivery of solutions. Local dynamos come to this new playing field with inherent advantages, including a deep understanding of local customers and dynamics. That position is likely to make them more formidable competitors to larger rivals than ever before.

Fulfilling Higher Consumer Expectations

The rising consumer class within many emerging markets continues to expand. What has changed over the past several years is consumers’ expectations. Thanks to smartphones and online shopping, consumers have access to more information about global trends in areas as diverse as fashion, education, and health. As a result, consumers in emerging markets are increasingly demanding access to the same high-quality products and services available in the developed world. Local dynamos have been quick to understand these demands, and they are able to meet changing consumer preferences while keeping costs low by adopting lean manufacturing and automation.

Vingroup. Think of something that increasingly demanding consumers desire, and chances are that Vietnam’s Vingroup is already offering it: Well-designed apartments—check. Shopping malls with both local and international brands—check. International schools to educate their children and hospitals to deliver quality health care—check, check.

The conglomerate was founded in 1993 by Pham Nhat Vuong—Vietnam’s first billionaire. The vision: to deliver a modern, middle-class lifestyle to Vietnamese consumers. The company has launched projects with a total of 10,000 affordable, high-quality apartment units, with plans to bring a total of 300,000 apartments to the market within the next five years. It has built 46 Western-style shopping malls (another 45 are under construction), six hospitals, two clinics, four primary schools, and 11 preschools. The company also manufactures its own line of high-quality food products—a well-received move in a country where food safety is a major issue—and sells those products through its chain of supermarkets.

In the past two years, the company has expanded its reach within Vietnam, moving beyond the largest urban centers to penetrate some of the country’s smaller, fast-growing cities. Next up: the development of a Vingroup car designed for consumers who are moving away from the country’s traditional reliance on motorbikes.

TAL Education Group. This local tutoring company has positioned itself at the nexus of a powerful trend in China: the rising demand for education services that middle- and upper-class parents see as a way to give their children an edge.

The company has built a growing business by offering small classes and personalized tutoring through its 594 learning centers in 42 cities, including Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai. While the company continues to enjoy the robust growth of student enrollment in its physical learning centers, it is also leveraging digital technologies to enhance its offerings. TAL is using its well-developed dual-teacher model as the company expands into lower-tier cities, for example. The model calls for a teaching assistant to be physically present in the classroom while a more experienced instructor leads the class via live video. In addition, the company invests about 4% to 5% of revenues annually to digitize and standardize the business. This includes a centralized curriculum development process, standardized training for teachers, and adaptive learning, an approach that uses computer-based lessons to assess student performance and tailor the instruction plan accordingly. The company’s model has allowed it to generate revenue growth at a rate of almost 50% per year from 2013 through 2017.

El Puerto de Liverpool. This Mexican department store company, commonly known as Liverpool, has delivered robust growth by making high-quality apparel and goods accessible to consumers in Mexico.

Like many of its competitors, Liverpool has focused on wealthier customers in large metropolitan areas. But the company has also opened stores in smaller Mexican cities. These outlets, under both the Liverpool and Fabricas de Francia brands, give middle-income consumers access to a wide assortment of products—including apparel from big-name companies, such as Gap and Banana Republic, and gourmet foods—at reasonable prices. More recently, the company acquired Suburbia, a clothing retail chain that caters to younger, bargain-conscious shoppers, and has been aggressively opening stores under that brand as well.

At the same time, Liverpool has taken aim at the limited availability of consumer credit in Mexico. In 2011, the company launched a credit card operation focused largely on low- and middle-income consumers. Today, that business boasts 4.4 million cardholders, making it the largest nonbank credit card issuer in the country, accounting for about 45% of Liverpool’s consolidated earnings before interest and taxes.

Developing Digitally Native Business Models

Local dynamos are often disrupters, entering existing markets with new, digitally based business models. And the high levels of mobile-phone penetration in many emerging markets allow them to scale digital businesses quickly.

YY. Chinese player YY has developed its own, wildly successful business model in the live-streaming entertainment market. YY’s roots date back to 2005, when David Xueling Li started a gaming portal called Duowan.com. YY now boasts an average of 117 million Chinese users every month—making it the largest live-streaming company in the world.

The company primarily streams performances by artists who are amateurs, running the gamut from singers and dancers to comics and self-made streaming personalities who riff on life and love in China. But while competitors primarily chase advertising dollars, YY largely monetizes its content in other ways—including through fees earned when viewers buy virtual gifts (essentially a donation) for performers or purchase virtual goods to use in online games. The company’s gambit has paid off: revenues, on average, doubled annually from 2010 through 2015 and have continued to grow in excess of 40% per year since then. And the company has ambitious growth plans for the years ahead, including efforts to increase the number of viewers making virtual gifts and to expand into some markets outside China.

CarPrice. The market for selling a used car in Russia is large—but it has not been overly efficient. More than 5 million used cars worth in excess of $30 billion—compared with sales of just 1.6 million new cars—are sold in Russia each year, according to recent estimates. But owners looking to sell have historically had just two options. The first is to sell the car to buyers directly. This approach generally garners a good price but requires a lot of time and effort, and it comes with significant paperwork and some risk. The other option is to sell to a used-car dealer. This approach is fast and carries a low risk, but the person selling the car typically nets a payment for the vehicle that is lower than market price.

Enter CarPrice. The company built the first online, real-time auction for used cars. Car owners fill out paperwork online and then take the vehicle to one of CarPrice’s 80 branches, where the company inspects the car, rates its condition, and checks that all the paperwork is in order. (This prevents the all-too-common problem of a buyer taking possession of a car only to find that there are liens or some other legal problems related to the vehicle.) Once those boxes have been checked off, CarPrice conducts a 30-minute online auction for the car with about 23,000 participating auto dealerships. If the seller likes the final price, the money is immediately transferred to his or her bank account.

Yandex. Often described as Russia’s tech giant, search engine company Yandex effectively cemented its lead in Russia early and has never looked back.

The company’s search engine was highly localized and easier for Russian speakers to use initially than the search engines offered by most of its rivals. And Yandex exploited that first-mover advantage, keeping pace with such search innovations as the development of personalized new services and a popular e-commerce platform. More recently, the company has moved into the next generation of search, launching an Alexa-like personal assistant dubbed “Alice.”

Yandex has leveraged its dominance in search to expand its offerings, including in transportation. The company’s taxi-hailing and map apps are widely used in Russia. Indeed, Yandex’s foothold in both businesses is so strong that it created a formidable barrier to Uber, which attempted to grab share in the Russian market. As a result, Uber struck a deal with Yandex in 2017 under which the two parties formed a ride-hailing and food-delivery company, with Yandex holding a majority stake in the new operation.

Creating Digital Ecosystems

A number of digitally native local dynamos are building powerful partnership ecosystems to expand and enhance their products and services. These arrangements are a far cry from the traditional partnerships that many companies have formed in the past to strengthen their supply chains or gain access to new technology. These ecosystems typically involve large and diverse sets of partners, outside the company’s industry, that can help the company rapidly develop compelling new offerings.

Indian e-wallet company Paytm has successfully cultivated a powerful digital ecosystem. Founded in 2010, Paytm allows a shopper to scan a merchant’s QR code on his or her mobile phone—and then simply enter the amount needed to pay that merchant.

The company leveraged this model to build relationships with millions of local mom-and-pop retailers in India. At the same time, Paytm created an online shopping mall that allows small brick-and-mortar shops with no internet presence of their own to advertise and sell their goods. The company also struck a deal with NPCI in 2017, under which Paytm offers a digital debit card to its e-wallet customers. Customers cannot use the Paytm e-wallet to make purchases on some sites, such as Amazon and Flipkart, so the new digital debit card fills in that gap.

The company’s links to local retailers in particular positioned it to capitalize on the government’s move in November of 2016 to ban 500-rupee and 1,000-rupee bills. From the autumn of 2016 to the autumn of 2017, the number of offline merchant partners on Paytm’s system skyrocketed from less than 1 million to 8 million, while the number of users nearly doubled, from 147 million to 280 million.

Expanding Service Offerings

Thanks to global connectivity, the expanding abilities of digital and analytics, and the growth of available data, companies can provide compelling services in addition to the products they offer. Many companies develop a portfolio of services around their traditional businesses, adding value to their offerings, while others go a step further and essentially offer access to their core product as a service, often referred to as “servitization.” Local dynamos are increasingly tapping into opportunities in both areas.

Intex. In recent years, Intex has undergone a dramatic transformation. The company was an early entrant in the mobile-phone market in India, but intense competition for mobile handsets from Xiaomi, among others, prompted Intex to rethink its strategy. While the company is still a player in that market, it has built up a healthy new business in televisions and IT accessories, such as speakers.

A key part of Intex’s winning formula is its focus on value-added services, including a network of centers for the service and repair of Intex products. Today, the company owns 50 of its own Master Care centers with another 1,500 owned by independent operators. The company struck a deal in 2016 with Tata Teleservices to launch Intex MyWallet, a mobile-wallet app that is preloaded on Intex phones and available for free on all Android phones, regardless of manufacturer. And the company has expanded the health care apps on its phones with features such as a daily health tracker and live coaching. Intex expects value-added services, which accounted for 10% of revenues in 2016, to grow significantly in the years ahead.

Movida. The success of ridesharing companies reflects the servitization trend in transportation—essentially replacing car ownership with a service. Rental-car company Movida has been riding that wave but has adapted its offerings to the local Brazilian market.

Many Brazilian drivers for services such as Uber cannot afford to buy their own cars and instead use rental cars. Movida saw this trend and moved quickly to carve out a major portion of the ridesharing car rental market. The company expanded its fleet, adding a large number of specific models popular among Uber drivers. Other features—including allowing people to rent for 27 hours instead of 24 (effectively a discount for drivers) and providing WIFI in the cars—appeal not only to Uber drivers but to other client segments as well. Such moves, along with competitive rental prices, exclusive partnerships, and an efficient B2B team, helped the company emerge as one of the fastest-growing companies in Brazil, vaulting from 29 stores and 2,400 cars in 2012 to 246 stores and more than 81,000 cars in June 2018.

Raia Drogasil. Created in 2011 through the merger of two of Brazil’s largest drugstore retailers, Raia Drogasil doubled its store count and boosted its earnings before interest, taxes, appreciation, and amortization fourfold by 2017. That performance was thanks to a number of strengths, including the company’s popular brand, its prime retail locations, a relentless focus on efficiency, and overall excellence in the critical basics of retailing.

Now the company is poised for similarly robust growth in the years ahead. A key driver is Raia’s bet on the growing consumer demand for services and the corresponding impact on customer loyalty, or stickiness—critical in a sector where switching across brands is still the norm. Raia Drogasil is creating a special area within its stores, for example, to help elderly customers—a population that is expected to nearly double in Brazil in the next 15 years—with their medical needs. In addition, the company is building up a pharmacy benefits management operation that confirms eligibility and offers discounts to some 32 million employees at scores of large companies. And Raia Dragosil has a growing specialty retail operation that provides patient monitoring and patient medicine compliance for oncology and hepatitis C patients. Through such services, Raia aims to create a virtuous circle in which customers embrace those offerings, become more loyal to the retailer as a result, and then increase their spending and adoption of services.

Building Talent Advantage

Four years ago, we noted that local dynamos were beginning to compete with bigger rivals for talent. Since then, they have arrived—shedding any sense that they are second-class employers. They are able to attract and retain top-tier talent in their markets, in part due to their willingness to match the compensation and benefits offered by MNCs. In addition, many talented younger workers in emerging markets are looking for excitement and opportunity in their careers—something local dynamos can offer to them in their home countries. Finally, local company employees have the opportunity to rise to the top management ranks—an attractive prospect because the highest positions in MNCs are often held by individuals from the MNC’s home country.

IFLYTEK. The intelligent-speech and -language technology company has emerged as the leader in its field in China, thanks to the company’s deep bench of talent and its partnerships with external research groups and universities. IFLYTEK was founded in 1999 by six students at the University of Science and Technology of China. The company’s commitment to R&D is reflected in iFLYTEK’s workforce: roughly two-thirds of its 2,000-plus employees are researchers, while one in four employees has at least a master’s degree. And the company partnered with the Ministry of Science and Technology of China to build the country’s only national intelligent-speech and -language laboratory.

That investment in research talent has paid off. IFLYTEK is best in class in terms of speech recognition, with a 98% accuracy rate—no small feat considering the complexities and nuances of the Chinese language. More than 500 million people use the company’s iFLYTEK Input speech translation app; courtroom transcription services, hospitals, and business call centers rely on its speech technology. And iFLYTEK is now moving into hardware: the company launched a smart-home assistant called DingDong in 2015, and a smart microphone, a device that can be incorporated into appliances such as air conditioners and refrigerators, in 2017. In April 2018, it launched its updated smart translator for consumers—iFLYTEK Translator 2.0, which supports instant translation of all Chinese dialects into 33 foreign languages.

Equatorial Energia. In the first decade of the 2000s, the Brazilian energy distribution company CEMAR offered notoriously bad service. Given that rates were set in part on the basis of service quality, that issue, along with a bloated workforce and high debt levels, translated into low profitability. A private equity fund stepped in, bought the struggling company, and created Equatorial Energia as a holding company—kicking off what would become an impressive turnaround.

The key to that rebound? A radical overhaul of the workforce. About 25% of the staff was let go immediately. That cleared the ranks of low-performing, and often politically connected, employees. New talent was recruited from outside the company as well as from outside the industry. And new human resources policies were put in place, including performance-based compensation under which a significant portion of all employees’ pay was linked to hitting specific targets. With new leadership, operations dramatically improved, thanks to moves such as an ambitious modernization of the company’s control systems, and profitability rebounded. In 2012, Equatorial bought a second company and employed many of the same turnaround techniques.

Toutiao. China’s Toutiao has brought the power of artificial intelligence to the news aggregation business, developing algorithms that give consumers the news and videos they want. Launched in 2012, the company’s news app, Jinri Toutiao, is used by 120 million people every day, during which the average user spends about 74 minutes on the platform—more time than on Facebook or even WeChat.

To satisfy the company’s ambitions—which include continued rapid growth and international expansion—Toutiao aggressively hunts for the best talent in the industry. The company is known for paying top employees the highest salaries in the market. Total annual compensation for top performers often exceeds $3 million—well above the $1 million to $2 million compensation that AI engineers in China typically receive. And Toutiao isn’t shy about going up against the largest and most successful tech companies in China to poach talent.

Lessons for MNCs

Given the agility and creativeness of local dynamos, how can MNCs compete successfully against these players? We have identified three approaches for winning:

- Emulate the local dynamos. If MNCs want to follow the lead of local dynamos, they will need to deliver high-quality—and, where possible, customized—products. They should make sure they are at the forefront of harnessing new digital tools and look for ways to expand their reach and offerings through digital ecosystems. They must also take a close look at where local dynamos are finding service opportunities connected to their core business—and determine if similar services fit with their own business models. What’s more, they need to study how the local dynamos are attracting and retaining talent—and be sure they are matching those efforts.

- Play to their own strengths and advantages. MNCs need to fully exploit the advantages they have. This includes thoroughly leveraging any edge in scale and resources, investing to maintain and burnish their global brands, and using their global reach—and the opportunities that such a reach affords to employees—as they compete for talent.

- Leverage partnerships and M&A. Partnerships with both local and global companies can help MNCs create powerful ecosystems. These alliances can reduce market entry costs and allow companies to hand off activities that are better performed by companies with lower cost structures or strong local presence. At the same time, MNCs should look for strategic mergers and acquisitions to fill in critical local capability gaps or to establish or enhance the company’s foothold in a new market.

We have seen MNCs using a mix of these approaches in emerging markets. (See “ Why MNCs Are Still Winning Big in Emerging Markets ,” BCG article, March 2018.) In some cases, MNCs have had to fall back, reassess, and adapt their strategies. But the ones that are succeeding are the ones that were able to leverage their own strengths while tailoring their emerging-market strategies to local conditions.