For a pharmaceutical company, a major technology breakthrough or fast-track approval of a new drug should be cause for celebration. But happy times can quickly turn sour if the company lacks the necessary experience with commercial-scale production using a new technology or does not have the capacity to ramp up manufacturing.

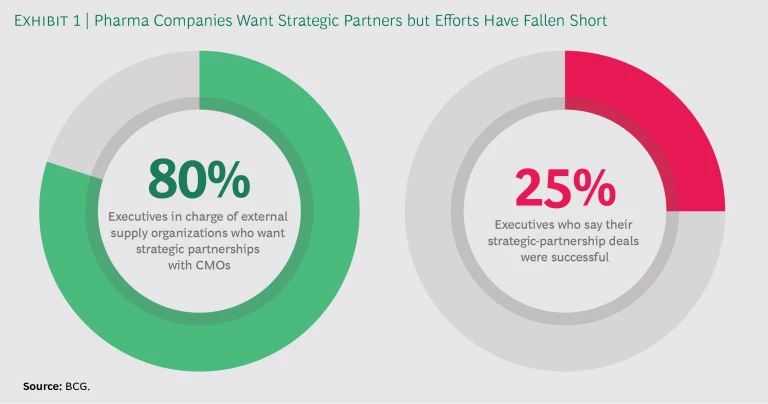

Increasingly sophisticated technology and other trends are converging to change pharma manufacturing, and companies are responding by shifting more production to contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs) that can work as trusted strategic partners. These partnerships not only help pharma companies gain access to new technology and add manufacturing capacity, they can also help mitigate risk and provide an avenue for entering emerging markets. Four out of five executives in charge of pharma companies’ external supply organizations—the departments responsible for working with outside providers of manufacturing and supply services—would like to establish strategic partnerships with CMOs. But creating and maintaining them is not easy. In fact, only a quarter of the executives who have entered into such partnerships say the deals they struck were successful. (See Exhibit 1.)

To improve the odds of a fruitful collaboration, pharma companies must determine which of several partnership options is best for a particular situation. Being clear on what they want, creating a playbook that can work as a template to structure a deal, conducting a rigorous financial evaluation of partnership proposals, and identifying contingencies to address unforeseen circumstances can help a pharma company and its CMO partner create a sustainable relationship that serves both parties.

When it works, a robust partnership can last decades. When GlaxoSmithKline expanded its respiratory franchise in the 1990s to sell more-sophisticated delivery devices, it partnered with Bespak to develop Diskus, a dry-powder inhaler used to treat asthma that represented a significant improvement over existing devices. By 2010, the companies had made 500 million of the devices, and as of 2018 the partnership was still in place.

A Convergence of Trends Makes Partnerships Increasingly Attractive

Pharma companies’ approach to managing the plant network has shifted. A decade ago, external supply functions were virtually nonexistent, and using CMOs on a decentralized, transactional basis was the norm. Since then, pharma companies have created global external supply organizations in order to centralize, standardize, and professionalize the management of CMOs and other manufacturing materials and services suppliers. As these organizations have matured, the executives who run them have come to appreciate the value of making the relationship with CMOs more effective.

This operational shift has coincided with the change in pharma portfolios from high-volume small molecules to biologics and specialized, often low-volume small molecules, which many companies don’t have the capacity to manufacture internally. But no company can afford to wait the five or more years it takes to build and qualify a new drug substance facility or a sterile drug-filling facility—or to build such a facility before a drug has been approved and, if it isn’t, risk being left with significant idle capacity. Instead, companies have turned to CMOs that can provide the necessary capacity and expertise. Outsourcing has grown to account for 22% of pharmaceutical manufacturing, creating a global CMO market worth $40 billion to $55 billion, according to industry estimates.

Despite the advantages of strategic partnerships, many factors conspire to derail them.

The health care industry has also shifted toward personalized medicine, with more pharma companies producing small volumes of medications that target very small patient populations, such as people with specific genetic traits. But building a whole new manufacturing plant to be used for only a few low-volume products is difficult to justify financially. In such cases, it is more efficient for a third-party partner to build the new technology platform and use it to make similar products for multiple pharma company partners.

At the same time, emerging economies are becoming more assertive in making local manufacturing a prerequisite to granting formulary access or reimbursement. That has led pharma companies to seek out local partnerships as a more practical, less expensive alternative to building a facility.

But despite the advantages of strategic partnerships, many factors conspire to derail them. They can be thrown off by changes in the pharma company’s priorities or network strategy—if it diverts to its internal network volumes that were originally promised to the CMO, for example. Problems can likewise arise when expectations differ about how the deal should work, with one party valuing the partnership more than the other, or when the team in charge lacks the required capabilities or tools.

Although such issues are common in many industries, they are amplified by the economics of the pharma industry. For a pharma company, ensuring a reliable product supply is essential to capturing the full margin from the sales price. In contrast, the CMO earns only a cost plus margin on its manufacturing costs. As a result, there are marked differences in the two parties’ ability to invest and in the relative weight placed on quality and supply reliability versus cost. This mismatch can lead them to mistrust each other, to operate with a win-lose mindset, or to be less than transparent about their respective goals.

Why Use a Contract Manufacturer?

Pharma companies that navigate these challenges can use partnerships to gain a number of operational and financial advantages.

Access to Manufacturing Technology. By partnering with a CMO, a pharma company can gain access to new manufacturing technology in a way that is less expensive, easier, and faster than building it in-house—and less risky than building it in-house before a product has been approved. Products in the pipeline can be crucial to a company’s future, so teaming up with a strategic partner rather than with a traditional supplier is often the smarter choice.

For example, a strategic partnership may be advantageous for a company that is shifting its portfolio from small molecules to large molecules or that is using new or relatively rare technologies, including high containment, hot-melt extrusion, soft-gel capsules, and antibody−drug conjugates (ADCs). When Seattle Genetics received accelerated approval of the ADC brentuximab vedotin, the company extended its partnership with Abbott Laboratories to manufacture the antibody and went into a separate partnership with Piramal to manufacture the cytotoxic drug. A CMO can likewise give companies access to advanced delivery devices such as dermal patches, inhalers, and continuous-release mechanisms. Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, for instance, struck a deal with Antares Pharma to make autoinjectors, including the migraine medication sumatriptan.

A strategic partnership can also help a pharma company that is shifting its portfolio away from a product that represents a large portion of revenue but is decreasing in value. With the CMO manufacturing the older product, the company can concentrate internal capacity on newer, higher-value products. When esomeprazole, Pfizer’s prescription heartburn treatment, became an over-the-counter medication, the company lacked the technology required to manufacture the delayed-release, enteric-coated tablets marketed as Nexium. Instead of building capacity internally for an older product, Pfizer entered into an agreement with Catalent, which had the necessary manufacturing experience.

A strategic partnership can help a company that is shifting its portfolio away from a product that represents a large portion of revenue but is decreasing in value.

Increased Capacity Without Investing in New Equipment. By teaming up with a manufacturing partner, a pharma company can extend or add a product line without making a major capital investment (as Pfizer did in the example above). With comparatively few capital assets relative to its operations, a company has more flexibility to respond to market trends and, as a result, can generate greater returns on assets. (See When “Asset Light” Is Right , BCG Focus, September 2014.) A CMO can also help a company deal with unpredictability in the demand for products that have yet to launch or be approved by regulators. For example, as Bristol-Myers Squibb’s biologics portfolio matured, uncertainty about how future demand would affect commercial volumes led the company to both expand internal biologics capacity and partner with Samsung BioLogics to secure additional flexible manufacturing capacity.

Reduced Risk. The absence of a backup plan in the event of a natural disaster, an unexpected surge in demand, or some other emergency can create major supply disruptions. But for a pharma company, building redundant manufacturing capacity internally for every major product is prohibitively expensive. Partnering with a CMO can be the next best thing.

A pharma company’s capital costs are typically lower than those of a CMO, making it easier to undertake major capital investments. But it’s hard for a pharma company to commercialize extra capacity if the expected volume does not materialize. In contrast, a CMO that co-invests with a pharma company can reduce its exposure by marketing excess capacity to other customers. This was among the reasons why Sanofi, the French pharma company, and Lonza, a Switzerland-based biologics CMO, announced a joint venture in 2017 to build a biologics production facility. (See “How a Pharma Company Used a Joint Venture to Expand.”)

How a Pharma Company Used a Joint Venture to Expand

How a Pharma Company Used a Joint Venture to Expand

The strategic partnership between Sanofi and Lonza is an example of the benefits to be gained when a pharma company’s external supply organization teams up with a CMO, including increased capacity and flexibility and decreased risk. When Sanofi’s portfolio shifted to biologics, it needed to build out capacity and capability for new products before it knew how well they would sell. At the same time, Lonza was looking for capital to expand its manufacturing capacity and capabilities. The companies met their individual needs by launching a joint venture to build a large-scale biologics production facility in Visp, Switzerland. Lonza constructed and operates the facility, and the partners share capacity commensurate with their equity in the venture.

The arrangement gives Sanofi access to extra biomanufacturing capacity should it be needed to support increasing demand for the company’s biologic therapeutic products. It also helps Sanofi react quickly to fluctuations in demand, reinforcing the company’s ability to launch high-quality, next-generation biologics and ensuring that patients have consistent access to medications.

For its part, Lonza is free to market any share of capacity dedicated to Sanofi that the company doesn’t need, as well as any other unused capacity. In addition, the joint venture gives Lonza needed capacity to respond to growing demand from potential customers for large-scale cultivation of mammalian cells used in the production of therapeutic proteins.

Access to Local Markets. Even before the current wave of protectionism, emerging markets had begun imposing localization requirements on foreign pharma companies, often with the goal of building up their own industry and expertise. One way to meet such requirements is through strategic partnerships with either privately owned CMOs or CMOs owned or operated by public agencies or local governments. Pharma companies that strike localization deals benefit by getting fast-track marketing authorization in the country, and they are likely to be better positioned in formularies and to be approved for public-payer reimbursement.

Localization requirements vary by country. In their simplest form, they may be limited to redressing or repackaging in a local warehouse. Other countries may require manufacturing the drug locally. Pharma companies can construct local plants, but that is expensive and the result is often a subscale facility that is costly to operate. A more effective way to fulfill manufacturing requirements is to partner with a local CMO that can itself partner with multiple pharma companies.

Bristol-Myers Squibb expanded its business in Brazil by signing a technology transfer agreement with Farmanguinhos, a pharmaceutical laboratory run by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The company agreed to transfer manufacturing and distribution of the antiretroviral medication atazanavir, marketed as Reyataz, to Farmanguinhos and to train its staff in exchange for approval to sell the drug in Brazil. In Russia, Sanofi Pasteur launched a technology transfer partnership with Nanolek in 2015 to produce the combination vaccine Pentaxim there. Also in Russia, Bayer HealthCare is working with multiple partners focused on full-cycle manufacturing, including a partnership with Russian manufacturer Medsintez, struck in 2012, to make pharmaceuticals used in the treatment of infections and neural disorders.

Varieties of CMO Partnerships

A pharma company may maintain basic, transactional outsourcing agreements with some suppliers and strategic relationships with others, with its overall plant network strategy dictating the best conditions for each. Technologies to which the company has a long-term commitment are especially well suited to strategic partnerships, since large-scale commercial production is difficult to transfer once it begins at a specific location.

Strategic alliances typically share some common characteristics. The parties benefit more from partnering with each other than with a different business. The partnership represents a significant, often critical portion of each organization’s business and is built on a high degree of transparency and trust. In addition to financial benefits, the arrangement leads to improved training, innovation, and flexibility.

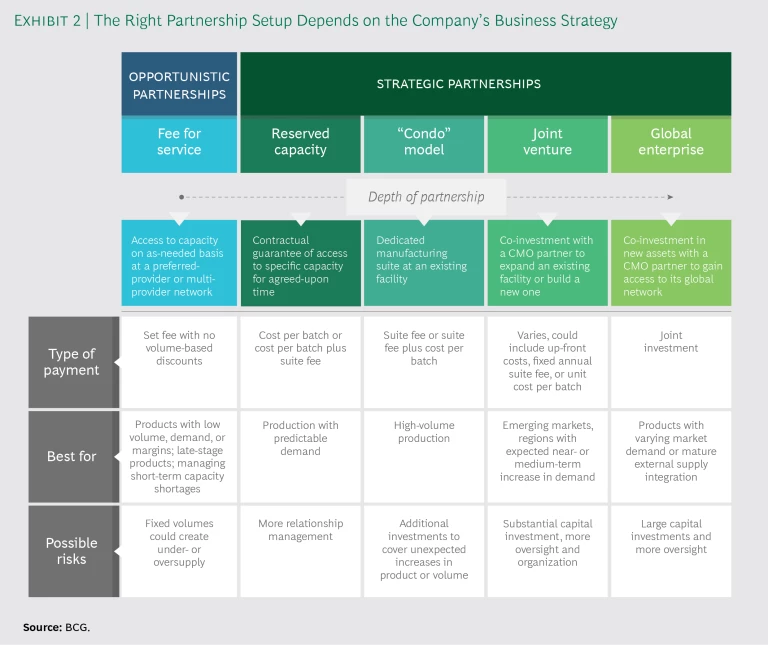

Partnerships range from very basic supply agreements to complex investments in production facilities that the partners jointly build and run. The appropriate form depends on the pharma company’s portfolio and business strategy. (See Exhibit 2.)

Fee for Service. Traditional fee-for-service arrangements remain the most common partnerships between pharma companies and CMOs, and companies often use them as a baseline against which to evaluate the incremental costs and benefits of closer relationships. In fee for service, the pharma company purchases capacity on an as-needed basis from a single preferred partner or network of providers.

Deals typically are arms-length agreements that cover products for which there is low or inconsistent demand. They can also be used to meet a one-off need for specific capabilities or to manage a short-term shortage of in-house capacity. Companies can use fee-for-service arrangements to outsource lower-margin or late-stage products or products that have lost exclusivity and are seeing volumes decline as a result.

The CMO in a fee-for-service deal is paid on a cost-per-batch basis with little or no discount for volume. The agreements generally involve fixed volumes for specific products, giving the pharma company limited flexibility to add products or to scale production up or down as needed. That can lead to undersupply, in which case the company might need to find another manufacturing source to keep up with demand. Or it can lead to oversupply if demand does not materialize, which can result in significant write-offs of expired products. On the upside, fee-for-service agreements require no capital outlays and only limited management of the relationship.

Reserved Capacity (“Take or Pay”). This is the most basic form of strategic partnership, with the pharma company buying a set amount of capacity for an agreed-upon time. The company is penalized if it doesn’t use the agreed-upon volume (hence, take or pay), so these arrangements are best suited to situations in which the company can reasonably predict a base level of demand.

Take-or-pay arrangements offer more flexibility than traditional fee-for-service arrangements because they allow the pharma company to substitute products or change production schedules, which helps mitigate the risk of under- and oversupply. They also help the company avoid large capital outlays but require more relationship management, especially in instances where volumes are unlikely to be met, products need to be switched, or production timelines have shifted.

In take-or-pay partnerships, payment is by the batch with an agreed-upon minimum, or by the batch plus a suite fee that includes a minimum volume with a lower per-batch cost. The fee structure makes this model most attractive to pharma companies producing at large volumes.

Dedicated Suite (“Condo”). In this arrangement, the pharma company co-builds or moves into a dedicated suite within an existing facility owned by a CMO (and in compliance with current good manufacturing practices, or GMP). The company may staff and operate the suite itself or pay to use the CMO’s personnel. Sometimes the CMO will manage a “condo community” of multiple pharma company partners, each occupying its own dedicated suite.

Not all CMOs prefer this model because of the complexities inherent in having employees of third parties running parts of their site. Pharma companies like it, though, because they have more control over products, production volumes, and timing. If the company’s product line or volumes increase, however, it might outgrow the suite and need to invest in additional capacity.

Companies that staff their own suite in a condo-style partnership pay a suite fee; if they use CMO personnel, they pay a suite fee plus cost per batch. Like take-or-pay agreements, condo partnerships are financially attractive for pharma companies producing at higher volumes, since they must bear the cost of any underused manufacturing capacity. In some cases, the CMO may offer spare capacity to other parties, allowing the pharma company to recoup some of the cost.

Joint Venture. The most advanced strategic partnership is a joint venture in which a pharma company and a CMO co-invest in a dedicated, GMP-compliant facility, either constructing a new building or expanding an existing one (as in the Sanofi–Lonza partnership described earlier). A joint venture with a local CMO is a common way for a pharma company to enter an emerging market such as China or Russia, but it is rarer in more established economies. Joint ventures are also well suited to places where a healthy near- or medium-term increase in demand for certain products is expected.

Joint ventures offer a pharma company more control and flexibility than other types of partnerships, while helping the CMO decrease its capital outlays. But they require pharma companies to make large capital investments and to provide the oversight and organization needed to build and manage a physical plant.

A joint venture can be fully fixed, with the pharma company making an up-front investment; it can be fixed per year, with the company paying the CMO an annual suite fee; or it can be fully variable, with the company paying a unit cost per batch. Ventures can also be structured so that the pharma company pays the CMO a licensing fee or royalties.

Global Enterprise. In a type of strategic partnership that has become popular outside the pharmaceutical industry, the company and the CMO co-invest in new assets in such a way that the company gains access to the CMO’s entire global network. These partnerships make sense in situations where product demand varies among markets, where near- or medium-term demand is expected to be high, or where the company needs volume and capability across multiple products. Global-enterprise partnerships require large capital investments and company oversight. The tradeoff is a significant amount of flexibility and control, ensuring supply if a product takes off as well as access to a global supply network, more products, and different markets.

Global-enterprise partnerships are common in the consumer electronics and automotive industries, where the integration of external supply chains is mature—Apple’s partnership with Foxconn and Toyota’s with Bosch are examples. Until now, pharma companies have not pursued this type of deal, in part because few CMOs have the end-to-end manufacturing capabilities needed for them to work. However, as both pharma companies’ external supply operations and CMOs become more mature, global-enterprise partnerships may begin to materialize.

Evaluating and Structuring Strategic Partnerships

Even the most well-intentioned partnership between a pharma company and a CMO can develop problems without careful planning. Our client work has revealed several key factors to consider when evaluating and structuring these relationships. Discussions about the reasons for embarking on a partnership, what it should cover, and how it should be structured financially must begin well before a company starts to solicit potential partners.

Discussions about the reasons for embarking on a partnership, what it should cover, and how it should be structured financially must begin well before a company starts to solicit potential partners.

Articulate the partnership’s purpose and value to the organization. A company’s external supply organization may perform a diligent analysis and determine that a strategic partnership with a CMO is the best option for sourcing a particular material or service. But if it fails to share the information internally, senior management may view the partnership as purely a cost savings measure and make decisions that could sour the deal. Likewise, the CMO must be willing to share enough information about its own operations for the external supply team to make an informed decision.

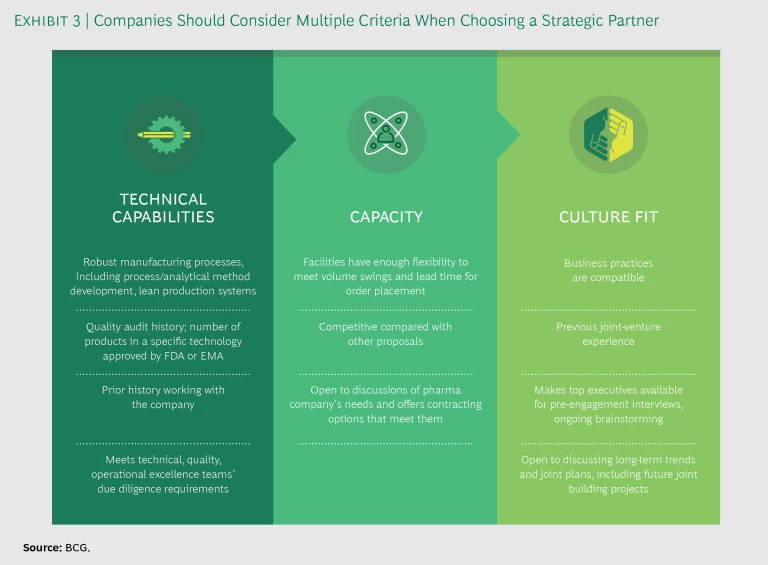

Develop a strategic-partnership playbook. Strategic partnerships are often so complex that the simple contracts used to cover basic manufacturing outsourcing agreements do not suffice. External supply teams need an overarching playbook, including contract terms and specifications covering all aspects of the deal. Another element should be a clear statement of criteria regarding the potential partner’s technical capabilities, capacity, and culture. (See Exhibit 3.)

The playbook should also clarify the amount of flexibility the company needs in order to make any last-minute changes that might arise within its own operations, while also being mindful that the CMO must have enough leeway to meet other customers’ needs. Likewise, it should detail the requirements of regulators and the pharma company’s quality assurance team, while recognizing the CMO’s need to comply with the quality standards of other customers. If the pharma company is contemplating a joint venture or some other sophisticated partnership, the playbook should spell out the exact financial and operational arrangement.

Finally, the playbook should address contingencies. For instance, if an increase in sales necessitates added volume that the CMO is unable to provide, the company might want the option of bringing manufacturing back in-house, finding an additional CMO partner, or investing in the CMO in order to expand capacity.

Conduct a financial analysis of partnership proposals. The use of multiple financial scenarios can help pharma companies evaluate potential partnerships against the costs of keeping manufacturing in-house (assuming that is possible). Companies should conduct three types of financial analysis to determine which strategic partnership would be the most advantageous: future volume, direct cost, and opportunity cost.

To analyze future volume, the company should review its long-range plans, estimated future pipeline volume, product demand, and the likelihood that new products will be approved by regulators—all of which the CMO partner will need to be flexible enough to handle. If the strategic partnership is to focus solely on a new technology for pipeline molecules, the company should also use advanced analytics to run scenario simulations. To assess the costs of each type of partnership, the company can analyze minimum-guaranteed-volume requirements, cost per batch, fixed costs with maximum number of batches, costs for additional services, and volume discounts. To analyze a potential partnership’s opportunity costs and risks, the company can incorporate other value measures, such as the opportunity cost of internal capacity for more valuable products, the risk of single sourcing, or the risk of entering a technological area in which the company does not have manufacturing experience.

Use contract terms to future-proof outcomes. A major obstacle to the long-term success of a strategic partnership is anticipated manufacturing volume that fails to materialize. When volumes fall short, the company and the CMO may quickly forget the reasons they partnered in the first place and revert to negotiating purely on price. These negotiations may then be characterized by mutual mistrust, which can be magnified when neither side has an adequate understanding of what the other has to offer. For the pharma company, that may mean not having enough information on the CMO’s services, total capacity, or competing priorities, while the CMO may not have a realistic estimate of the pharma company’s expected volume.

To avoid this risk, potential partners should be as transparent as possible—without sharing trade secrets or breaching confidentiality agreements—about volumes, capacity, and costs. Once work is underway, they can use KPIs or similar systems to track progress toward stated goals. They can also tie each other’s performance to clearly defined financial outcomes.

Contracts should cover situations that could change the nature or value of the relationship for one or both parties. These might include a new owner, a change in corporate management, or a shift in pipeline or network strategy. Contracts should also cover potential future conflicts of interest, such as the CMO’s manufacture of competing products or generics, one partner entering the other’s business, or significant shifts in volume or CMO capacity.

Pharma companies and their CMO partners can further future-proof their relationship by using financial tools such as options, futures contracts, milestone payments, and earnouts. Where appropriate, a neutral third party can collect data, facilitate negotiations, and help determine the right instrument, strike condition, and payoff.

Pharma companies have been slower than other advanced industries, such as electronics and automotive, to embrace strategic manufacturing partnerships with trusted CMOs. But these companies’ external supply organizations can no longer afford to hesitate. Striking such partnerships with carefully chosen CMOs through well-structured deals can help pharma companies expand capacity and gain access to cutting-edge technologies, which can lead to improved operating efficiencies and increased market share. Likewise, partnering with outside entities run by public agencies or local governments can help them gain access to emerging and lucrative new markets. Companies that do not take these steps risk falling behind. As time goes on, that could be a tough pill to swallow.