This is the first in a series of publications on the changing face of infrastructure investing.

The world of infrastructure investing is undergoing structural shifts that require investors to take a more active role in managing their portfolios. Investors can no longer count on generating double-digit returns from core assets with stable risk profiles. Instead, they need to broaden their definition of infrastructure; develop a transformational plan to grow, improve, and reposition investments; and recruit an investment and management team that can manage companies in an environment of greater uncertainty and complexity. No longer functioning merely as caretakers, they must act similarly to private equity investors, who seek to both rationalize and revitalize their portfolio companies in pursuit of outsized returns.

For traditional infrastructure investors, this shift has massive implications for their analysis of potential projects, their willingness to assume operational risk, the skills necessary to manage their investments, and a host of other issues. In subsequent publications, we will return to those issues in greater depth. Here, we will focus on what has changed and—at a high level—what investors should be doing in response.

The Changing Face of Infrastructure

Until very recently, the fundamental nature and service patterns of infrastructure projects had not materially changed in decades, perhaps centuries. Such projects tended to be large, fixed, government-financed structures designed to enable the provision of an essential service, often through a natural or regulated monopoly. From the outside, bridges, seaports, and water treatment plants don’t look much different today than they looked long ago. But five market forces are shifting the playing field for infrastructure investors in crucial ways.

Flagging Government Commitment. As a result of fiscal constraints, governments—historically the funder of first resort for infrastructure—are investing insufficiently in new projects or the rehabilitation of existing facilities, despite the critical need for them. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that the US alone is looking at an infrastructure funding gap of $2 trillion from 2016 to 2025; and in an analysis of 56 countries and seven infrastructure sectors, the Global Infrastructure Hub, a G20 initiative, identified a funding gap of $15 trillion from 2016 through 2040. Private capital must accept a growing role to ensure the delivery of essential services in light of the paucity of public financing.

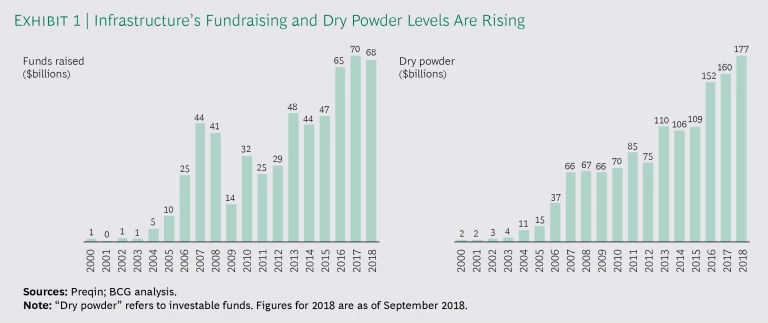

Investor Demand. Over the past decade or so, investors have flocked to infrastructure projects. Both the amount of money raised each year and the amount of dry powder—investable funds—on hand are rising. (See Exhibit 1.)

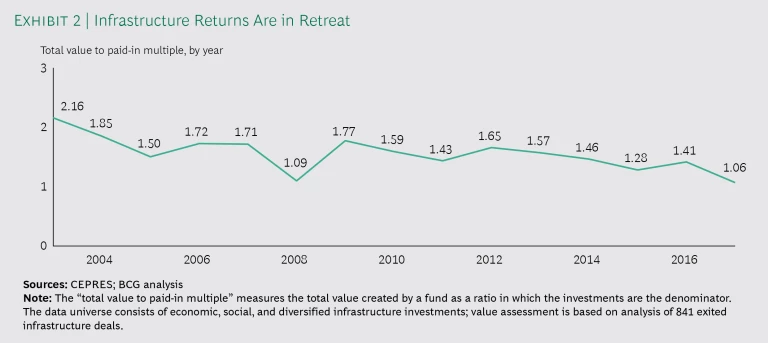

However, investors tend to chase a group of traditional infrastructure assets—including toll roads, airports, and electrical-generation facilities—that provide predictable, long-term cash flows. The resulting influx of money is driving down returns, which have been cut in half. (See Exhibit 2.) To reap rewards comparable to those that investors gained in the past, today’s investors must look beyond the core assets and develop strategies to generate additional service income.

Technological Innovation. Today, digital technology is fundamentally changing infrastructure in ways that create opportunities, disruptions, and competition. The opportunities lie in technology’s ability to open service channels, improve asset management, and widen the universe of investable assets.

Technological advances such as smart metering can enable infrastructure providers to offer new services, while Internet of Things technologies can support predictive maintenance capabilities. On another front, technological developments such as household micro water treatment facilities are shrinking the size of infrastructure so radically that it has begun to resemble equipment, and this category may emerge as a new class of investable assets.

Technology’s disruptive force is also apparent in infrastructure investing. For example, self-driving cars can undercut the value of underlying infrastructure assets such as toll roads and parking garages.

Finally, technology is enabling increased competition. In the market for traffic flow data, for example, device makers such as Apple, online platforms such as Google and its subsidiary Waze, automakers, and manufacturers of smart transportation equipment will be competing and cooperating.

The days of investing passively in infrastructure are over. Investors need to analyze all of these factors when assessing an investment’s risks and returns.

Customer Behavior. Many users and customers of infrastructure projects expect greater customization, responsiveness, and innovation, of the sort they have grown accustomed to in other aspects of their lives. This expectation heightens the degree of difficulty for owners of infrastructure—because they must add a service component to their offering—but it also creates revenue-generating opportunities.

Regulatory Evolution. For private investors to play a larger role, governments must be willing to offer them relief from outmoded regulations that constrain infrastructure owners by supporting traditional monopolies and restricting public-private partnerships. Companies such as Airbnb have achieved their greatest success in markets in which they maintain a productive relationship with regulators.

A New Playbook for Investors

These developments suggest that the infrastructure investment market is both broadening and deepening. It is broadening to include a new class of smaller, distributed, tech-intensive infrastructure assets. It’s deepening in the sense that traditional infrastructure projects, which are not disappearing, now require more active management and the development of alternative revenue streams.

In this new era of infrastructure, investors must play a double game, recalibrating their expectations for and their approach to traditional infrastructure even as they pursue new opportunities. Here are four ways to prepare for the future of infrastructure investing.

Fill the void. As government’s role in infrastructure recedes, sophisticated investors have an opportunity to fill the gap, taking over some of the roles that the public sector has traditionally played in return for greater control over deal structure and financial return. Several governments, including Australia and the US commonwealth of Pennsylvania, now allow private investors to make unsolicited bids on projects. Meanwhile, the Canada Infrastructure Bank is poised to redefine public-private collaboration in infrastructure by providing bridge financing as a way to foster private investment in projects.

Focus on value-added services. As some forms of infrastructure acquire a service layer—thanks to technological innovation and consumer preference—investors will need to broaden their metrics to capture the potential for ancillary income. They will also need to assess their management team’s ability to deliver on a business plan rather than just managing an asset, even with regard to traditional assets. For projects such as seaports and airports, investors should analyze how technology and services can improve investor returns, while also being alert to disruptive forces that could alter demand. For example, 3D printing and advanced robotics could dislocate manufacturing industries, disrupt supply chains, and reduce container-shipping volume.

Create new underwriting standards. As infrastructure becomes less centralized and monolithic, consumers and commercial customers may begin owning and operating their own elements of a broader infrastructure network within a business, school, or home. The shrinking and democratization of infrastructure will alter how investors view both legacy assets and new opportunities, such as household water treatment facilities. Meanwhile, battery storage will help smooth the supply of renewable energy, thereby simultaneously reducing the need for power plants geared toward peak capacity and encouraging a distributed network of assets.

For investors to participate in these new decentralized infrastructure networks, the underwriting model must permit efficient deployment of capital across a greater number of small transactions. This is already starting to happen. Investors are bundling and packaging micro-projects into platforms backed by a management team and committed equity lines.

Acquire new capabilities. Whether investors decide to broaden their approach, deepen their approach, or both, they must become more active and more discerning in identifying the types of people they need to hire. Increasingly, investors must recruit operationally savvy executives who can actively manage businesses or who have specific expertise in such areas as post-merger integrations, capital and operating spending optimization, and commercial excellence. Global Infrastructure Partners, for example, maintains teams of operating executives who work side by side with the management teams of its portfolio companies.

The new normal of infrastructure investing requires managers to think dynamically about how changes in competition and in consumer investments and technology will affect their current portfolios and their future investments. Owning the infrastructure that provides an essential monopoly service will no longer suffice. Investors need to view themselves as the owners of a competitive business that seeks to generate new revenue sources and improve services while scouring the landscape for the next disruption. This imperative is especially critical for current owners who have the opportunity to take advantage of their monopoly position to build new strengths and focus on value creation before the tide turns. It’s time to start thinking and acting like a private equity investor.