This report is the second in a series on changes in the parcel and express industry.

Last-minute rerouting, guaranteed deliveries within two-hour windows, drop-offs in places that don’t have street addresses: parcel delivery companies have been talking about all of this for years. That this future has arrived is no surprise. The surprise is who is leading the way.

Startups and giant e-tailers, seizing the opportunity created by digital technologies and the rise of e-commerce, are innovating in ways that are upending the industry. These newcomers are concentrating their services in the areas where profit pools are the deepest and offering alternatives to products for which incumbents still charge a premium.

Incumbent deliverers are in a quandary. As new ways of achieving scale have emerged, the incumbents’ asset-heavy networks are losing relevance. In many cases, those networks and the legacy systems that underlie them are slowing incumbents’ embrace of new realities.

In this report—a follow-up to How a Digital Storm Will Disrupt the Parcel and Express Industry (BCG Focus, December 2016)—we take a detailed look at startups’ assault on existing business models. We also discuss strategies that incumbents can use to fight back, including rededicating themselves to their existing customers’ needs and developing their own digital capabilities. (See the sidebar below.)

Our Three-Part Series about Parcel and Express

This look at the assault by digital startups and e-tailers on the parcel and express industry is the second in a series that BCG is publishing.

Our first report discussed five trends that have reshaped the industry, including the deconstruction of the delivery value chain and the consumer’s increasing control.

Our next report will focus on what incumbents need to do to add the necessary in-house digital muscle. This includes overcoming barriers such as IT complexity, building up digital and data platforms, and conquering organizational inertia.

A Surge of Funding and Digitization in Parcel and Express

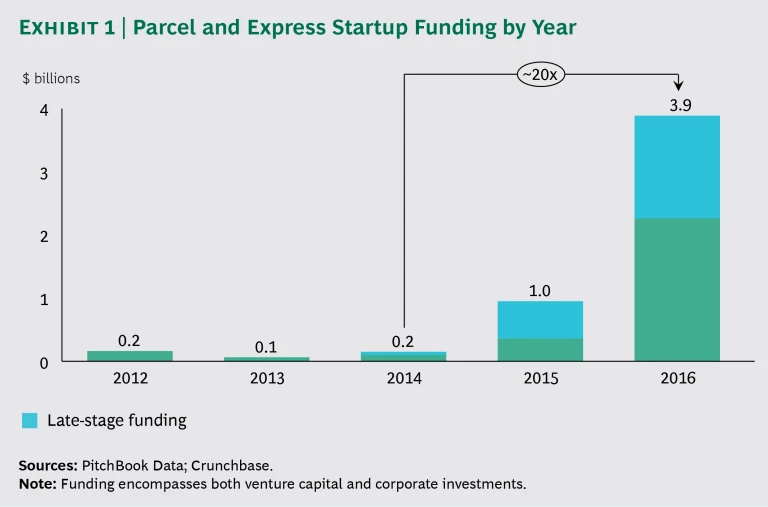

When the e-commerce boom began, little venture capital money was invested in parcel and express, a seemingly stable business with high barriers to entry. That has changed drastically in the last few years.

More than $6 billion has poured into the parcel and express sector since 2012. Investments as a whole increased some 20-fold and late-stage funding increased more than 30-fold from 2014 through 2016. (See Exhibit 1.) Ten startups have received more than $175 million in cumulative funding, and ten others have received more than $50 million.

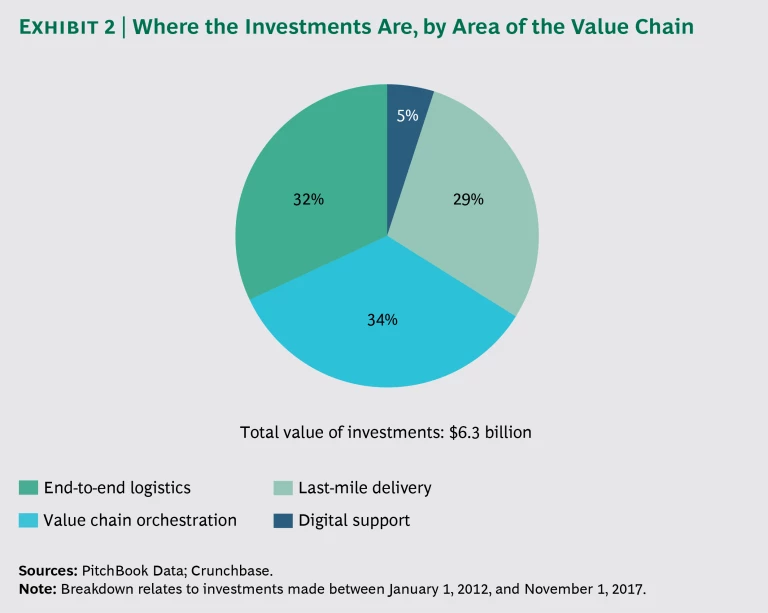

The startups receiving the capital are focused on four main business models (see Exhibit 2):

- First, there is value chain orchestration. The players in this category—light on assets and heavy on digital technology—position themselves as a new go-to option for parcel and express senders. They use senders’ preferences for speed, price, and ancillary services to select the optimal delivery company. Value chain orchestrators’ success depends on their ability to dissociate parcel and express incumbents from the senders that typically pay for deliveries.

- End-to-end logistics is the second business model we’ve identified. These startups likewise set out to become the senders’ new go-to source; they too have the effect (if they are successful) of dissociating senders from their long-standing parcel and express partners. End-to-end logistics companies, however, also offer third-party logistics services. The scope of their activities is thus a little broader than that of value chain orchestrators.

- Last-mile disruption is a third business model, and it has become part of the fabric of commerce in many big cities. The players in this category (whether they arrive on bicycles or in vans or have a booth near the checkout counters in retail stores) offer an array of new delivery options based on digital technology. They are dissociating a different relationship: the one incumbents have with package receivers.

- The fourth business model is what we call digital support. These companies are applying digital technologies—such as real-time route planning and artificial-intelligence-led pricing—to traditional steps in the value chain. Many of their tools—including connected and automated vehicle technology, 3D-vision navigation, and robotic automation—fall into the network operations category. Digital supporters all want to partner with, and get business from, incumbents by making the incumbents’ supply chains more efficient.

In analyzing the flow of funds and the startups’ business models, two conclusions stand out.

First, only a small amount of the funds has gone to companies that actually support traditional deliverers; the overwhelming majority of the funding (about 95%) has gone to companies that disrupt them.

Second, these disruptors have pretty much all set out to drive a wedge either between incumbents and senders or between incumbents and receivers. To the extent that these newcomers succeed, the profit pools will shift in their direction, and incumbents will be left as suppliers of commoditized services.

The Business Models at Work

To look more closely at some of the startups is to understand that the threats are not abstractions—they are proximate and very real.

Take Deliv, which is an example of the third business model: last-mile disruption. In the 35 US markets where it operates, Deliv offers same-day delivery, and it achieves this without owning any heavy assets. Instead, Deliv uses a crowdsourcing model, which allows it to provide substantially the same service as a postal or parcel incumbent with nothing like the same sunk cost. Some 4,000 businesses and 25 of the biggest US retailers have partnered with Deliv, seeing it as a way to counter Amazon’s increasing reach. UPS itself participated in a 2016 funding round in which Silicon Valley–based Deliv raised $28 million.

Another last-mile disruptor, Fetchr, is in Dubai. Fetchr’s workaround for a common challenge with Middle East deliveries (the fact that street addresses often don’t exist) has led to a service that may be valuable elsewhere in the world. Helped by $60 million in funding, Fetchr has built a service in which shippers and receivers select their pickup and delivery locations by leveraging the GPS technology in their smartphones. This enables flexible deliveries because packages can be delivered to wherever the receiver happens to be.

As if the threat from head-on competition wasn’t enough, there are other digital startups that don’t fit strictly into the parcel and express category but can’t be ignored. Who’s to say, for instance, that Uber Eats—the fast-growing offshoot of the ride-hailing giant—won’t eventually deliver regular e-commerce packages in addition to perishable items? If and when Uber Eats does this, its huge fleet and capacity for fast, flexible deliveries could make it a force in parcel delivery overnight.

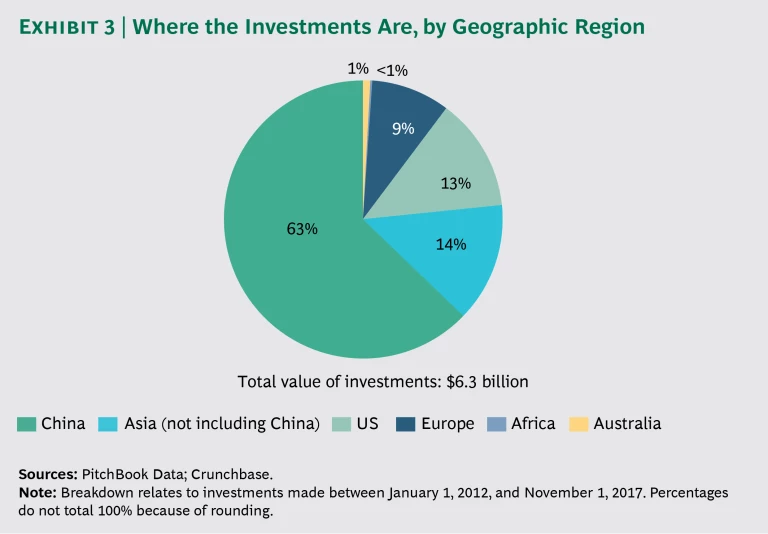

China as the New Hotspot for Investment

Another new development that incumbents need to start tracking is all the logistics company formation that’s happening in Asia. The noteworthy startups aren’t concentrated in Silicon Valley anymore. In fact, the bulk of the investments in the last five years—more than 75% of the total—have been in Asia, with Chinese startups alone getting $4 billion. (See Exhibit 3.) Most of this money has gone into just six companies: Cainiao, Best Logistics, New Dada, Hive Box, Yimidida, and Yunniao Logistics.

China is coming from behind in parcel and express, and a lot of the investment that’s been happening there is in network infrastructure: warehouses, trucks, planes, vans, and depots. For this reason, Western incumbents may be inclined to minimize the likely impact of these startups on their own businesses. They shouldn’t. In many instances, the new Chinese entrants are leapfrogging Western companies, notably in their response to changing customer expectations about speed of delivery. Five years ago, two-day delivery was standard in China for online purchases made from domestic e-tailers. Now, Chinese consumers increasingly expect same-day deliveries. In fact, deliveries in an hour or less are becoming more and more routine in dense areas. While this trend toward same-day delivery exists in several big Western cities including New York and London, it is more common in China.

Western companies may be inclined to minimize the likely impact of Chinese startups on their own businesses. They shouldn’t.

In any event, Western incumbents won’t be able to ignore the existence of Chinese companies for long. In the fall of 2017, Best Logistics—one of several logistics startups funded by Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba—completed an initial public offering in the US to expand its supply chain network. And Cainiao, another Alibaba-funded startup, is expanding in ways that will eventually allow it to compete in virtually every country in the world.

E-Tailers Rise as a Threat

In interviews done for this study, parcel and express companies made it clear that they consider e-tailers to be their biggest existing threat. The biggest e-tailers (such as Amazon in the US and Alibaba and JD.com in China) have amassed a stunning amount of power. And they are using that power: to dictate pricing, to punish recalcitrant shippers and reward compliant ones, and, in many cases, to start their own parcel and express operations, including making last-mile deliveries.

When they build their own parcel delivery capabilities, e-tailers often say that they are doing so because they are concerned that incumbent deliverers won’t be able to meet their customers’ expectations. It’s a plausible explanation. Reliability and speed of delivery, even during peak shipping seasons, have become nonnegotiable matters in the minds of most online shoppers. So has flexibility: most online shoppers want the option of either next- or same-day delivery, have come to expect notification and track-and-trace services, and are starting to look for rerouting options. In cases where traditional deliverers can’t offer these benefits, it makes sense for e-tailers to offer the benefits themselves.

But one might reasonably question whether this is the whole story. E-tailers that get into last-mile deliveries usually go beyond the basics—radically simplifying the returns process, as Amazon has done, or offering assembly and installation of products that require it. These moves suggest that e-tailers see delivery as a valuable way of strengthening the customer relationship—which is of course the core of their focus. To put it another way, large e-tailers view physical delivery as a service they want to control fully, so as to control the full customer journey. In sum, while it’s possible that e-tailers are getting into the last mile partly for the reason they sometimes give—to fill a temporary service gap—it would be dangerous for incumbents to buy that explanation too fully.

If large e-tailers’ move into last-mile delivery is a threat, it is also a flare in the sky illuminating an important opportunity.

Most incumbents are aware of the changes in their long-standing e-tailer relationships. In our interviews with them, we heard considerable concern about the logistics moves of e-tailers—not just in the last mile but in sorting and transportation. Most incumbents, for instance, are quite familiar with Amazon’s logistics activities, from the company’s plans to operate its own airline fleet to its experiments with delivery drones. The recent news that Amazon is starting up a logistics as a service offering called Shipping with Amazon, initially in Los Angeles but with the intent of rolling it out more broadly in the US, was a not a total surprise given Amazon’s continued forays into new sectors and industries.

There is considerably less appreciation, certainly on the part of Western parcel and express companies, of the logistics moves being made by Chinese e-tailers. Yet these moves are massive. For instance, JD.com, which is the world’s third-largest internet company by revenue, has built a sprawling logistics network. In addition to its 31,000 delivery personnel, JD.Com has more than 400 warehouses and thousands of distribution points, including some of the world’s most modern automated sorting centers. And Alibaba has pledged to pour $15 billion into logistics in the next five years. Much of that can be expected to benefit Cainiao, a logistics unit that, while largely unknown in the West, could shape the future of logistics globally. (See the sidebar below.)

China’s New Logistics Juggernaut

From the perspective of getting incumbents’ attention, no Chinese company—and arguably, no startup anywhere—has been as consequential as Cainiao (also known as China Smart Logistic Network). Cainiao (pronounced SIGH-now) was created as a joint venture in 2013 by Alibaba to serve as that e-tailer’s logistics and delivery arm. In 2016, Cainiao received a $1.5 billion capital infusion, which it has used to continue developing its logistics data platform. In keeping with the trend of ever-faster deliveries, Cainiao’s goal is to be able to get a package to any location in China in 24 hours and to any location in the world in 72 hours.

Cainiao doesn’t consider vehicles and other capital-intensive assets its main investments. Instead, it is a digital, data-driven company—one whose purpose is to orchestrate other logistics companies. Cainiao matches merchants with more than a dozen major shippers in real time using its proprietary analytics platform. Merchants prestock products in centralized warehouses on the basis of past sales data, and many products spend less than 60 minutes in a warehouse before being loaded onto delivery trucks. Its mastery of data and its close ties to Alibaba, the dominant e-commerce provider in China, allowed Cainiao to handle about 17 billion packages in 2017, Cainiao’s third year of operation. (See the exhibit below.) That would be roughly 70% of all delivery volume in China.

Cainiao is investing in digital systems and gaining insights into both senders and receivers, as part of a strategy to dominate both ends of the delivery chain and ensure that its own platform is always the preferred one. As it makes these investments, Cainiao is clearly commoditizing the services of traditional logistics companies. There is no better example of the challenges facing incumbent deliverers in a digital era.

E-tailers are also the primary reason why incumbents are starting to worry about their B2B franchises. B2B used to be the biggest revenue source for many parcel and express companies and has remained an incumbent stronghold. But B2B customers are starting to look for more of what they get on B2C sites. The new expectation has been fanned by Amazon with its three-year-old B2B platform, Amazon Business. This has incumbent deliverers concerned that their dominance of B2B deliveries may, like the early dominance they had in B2C deliveries, fade.

If large e-tailers’ move into last-mile deliveries is a threat, it is also a flare in the sky illuminating an important opportunity. Only the very largest e-tailers can afford to operate their own delivery networks. Virtually all other e-tailers and every brick-and-mortar retailer regardless of its size needs a delivery partner. And the partner must be capable of more than just delivering something at a reasonable cost along a preset schedule. Other services are crucial if these shippers are to match the experience that consumers have come to expect in the age of Amazon.

That’s where the incumbents can come in. With their traditional brick-and-mortar assets, including retail outlets and post offices, incumbent deliverers can help smaller e-tailers and traditional retailers create new delivery and return options for parcel receivers. It’s a way for at-risk retailers to stay in the game. And it’s an important opportunity for incumbent parcel and express players.

Incumbents Trail Startups and E-Tailers in Digital Investing

To say that parcel and express incumbent players haven’t responded to the arrival of digital technologies in their industry, or haven’t innovated at all themselves, would be a misstatement. Incumbents have expanded their product offerings with better return solutions and more flexible deliveries. They have made significant investments in their own IT platforms, cutting into the lead that the digital startups have.

But incumbents have not made investments in new business models or been creative about moving into adjacencies. Their caution in embracing these expansion tactics is evident in their M&A activities. From 2012 to 2017, incumbents provided a mere 1% of the funding for logistics startups, leaving the field largely to e-tailers and venture capitalists. Of the more than 250 acquisitions made by parcel and express incumbents between 2012 and mid-2017 that BCG examined, only 31 appear to have been done to create an innovation advantage through technology.

Even more worrisome for incumbents is the insufficient investment that they have made in strengthening their sender and receiver relationships. Most people receiving a parcel or package from an incumbent deliverer today do not perceive much difference from what that experience was like 10 or 15 years ago. It’s the newcomers that are making the strides in receiver intimacy, which is what the industry calls it when rich data about parcel recipients leads to improved last-mile service.

Incumbents have not made investments in new business models or been creative about moving into adjacencies.

Four Critical Themes for Incumbents

How far we have come from five years ago, when the global boom in e-commerce was an unambiguous positive for many incumbent deliverers—a growth accelerant that seemed to exist in endless supply. No one knew how profoundly the parcel and express industry could change (though the postal services, already disrupted by digital forces, may have had an inkling). Certainly no one knew how quickly the funding for startups would accelerate once it began, how formidable some of the startups would become, or that almost all of the startups would go after the incumbent deliverers’ existing profit pools (versus aiming somewhere else and avoiding the risk of a head-on battle).

Nor did anyone know that the big e-tailers, which seemed to have their hands full, would step into the parcel and express delivery game themselves. No one knew, to put it less delicately, that the big e-tailers might in 2018 be positioning themselves to ditch the very delivery companies that helped them to succeed in the first place.

There could be more surprises coming—from distant geographies like China and adjacent players like Uber Eats—if incumbent deliverers do not adapt to the realities of a digital era. To have a chance of being the disruptors instead of the disrupted, here’s what needs to be on the incumbents’ agenda in the next few years.

Obsess Over Senders and Receivers

With all the new delivery options that have emerged, incumbents can’t rely on their reputations to keep senders and receivers from switching to new providers. Incumbents need to sense the wedges starting to separate them from their formerly steadfast customers as startups and e-tailers come forward with new propositions. Next to protecting their sender and receiver relationships, everything else an incumbent might do is secondary.

This means focusing on new customer expectations for speed, reliability, and flexibility and looking for ways to re-create the customer experience. Today’s “wow” factor is tomorrow’s table stakes. The most successful players will continuously rethink what they can do next to meet the needs of the senders who pay them and the receivers to whom they deliver.

Widen the Radar

Incumbents tend to worry about their home markets and about the head-on competitors they see daily. They aren’t as good at recognizing threats or opportunities that are outside their usual spheres of activity.

Incumbents should learn from both startups and e-tailers, which are entering the parcel and express field with new, inventive services. And they should keep an eye on developments across the globe. Particularly important to track are Chinese players, whose rapid emergence increases the likelihood that they will have an impact worldwide—whether as new competitors, partners, or innovation trendsetters. The broadened awareness won’t necessarily lead incumbents to completely reinvent what they do, but it will allow them to adapt more quickly. This is crucial if incumbents are to avoid disintermediation at the hands of fast-moving startups, e-tailers, and traditional competitors.

Go on the Offensive

Incumbents have the opportunity to become preferred partners, both to smaller e-tailers that haven’t built up a full range of logistical capabilities and to traditional brick-and-mortar retailers. As they mount their own high-stakes battle with the Alibabas and Amazons of the world, both smaller e-tailers and brick-and-mortar retailers of all sizes need to be able to offer first-rate delivery capabilities. They can get this through the physical presence and dense networks of incumbent deliverers. This presents a huge opportunity to incumbents over the next five to ten years.

Add Digital Muscle

To remain competitive in a digital age, incumbents must move to a new level of mastery in their use of data. Sophisticated analytics can shed new light on customer needs and spark innovative ideas. But this can happen only if incumbents move beyond what most are doing now in the area of digital—developing pilots and prototypes—and instead implement large-scale digital projects. This will require different organizational setups and different types of profiles in the incumbents’ IT organizations.

It’s certainly possible for incumbents to get some of what they need through partnerships or acquisitions. But you can’t be a smart buyer of technology if you don’t understand what you’re buying, and you can’t structure an effective partnership if you don’t have some impressive capabilities of your own to put into it. For these reasons, incumbents will need to develop core in-house digital skills and keep strengthening them.

Retaking the Initiative

Even among the incumbents that have thrived through the rapid changes of the last five years, there should be concern about what’s next. An increasingly large amount of money is being invested to get parcels to customers anywhere, at any time. New players, with new technology solutions, are entering the logistics space with each month that passes.

The real focus for incumbents should be on staying ahead of the changes in their markets and on avoiding disruption and commoditization. It’s all about being the first to anticipate what customers will need. To the extent that incumbents can do this, they won’t be the ones playing catch up.

Next in the series: the imperative for incumbents to build digital muscle.