The last two decades have seen principal investors, a group that includes sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), pension funds, and family offices, make significant changes in their portfolio composition. Prompted by declining yields in traditional asset classes and stronger returns in newer ones, funds have adjusted their risk profiles and shifted a growing share of their portfolio allocation into direct private equity investments .

To understand the changing landscape, The Boston Consulting Group interviewed representatives and experts from 20 major funds from around the world, totaling around US $5 trillion. This report examines the shift toward increased private equity and direct investment and looks at how funds need to adapt their governance and organizational models to maximize returns.

How Private Equity Became an Important Part of Fund Portfolios

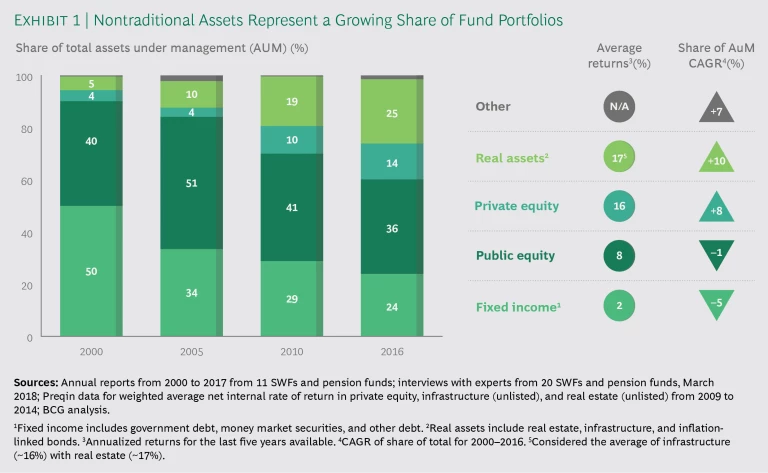

For many years, fixed income and public equity assets served as the backbone of most principal investor funds—comprising approximately 90% of all assets under management (AuM) in 2000. However, that long-standing investment tradition came into question as long-term yields in fixed income investments began to decline and public equity performance became increasingly volatile. Meanwhile, other nontraditional asset classes were thriving, led by private equity and real assets (real estate and infrastructure) that since 2000 have delivered a steady CAGR of 8% and 10%, respectively. (See Exhibit 1.) At one Canadian pension fund, for instance, fixed-income holdings went from 95% of total AuM in 2000 to just 16% by 2016, while private equity holdings grew from 0% to 19% over the same period.

For most principal investors, the shift to private equity and to taking a more active management role was jumpstarted by the financial crisis. During the recession, most traditional investment activity came to a halt. To manage risk and return and provide the financial sector with needed liquidity, a few SWFs chose to step in and back a handful of large direct equity deals. These included the Qatar Investment Authority’s investment in Barclays as well as the joint investment by Temasek and the Kuwait Investment Authority in Merrill Lynch. Those early deals, some of the first examples of direct private equity investment, provided an initial proof of concept.

Later, as volatility in the public equity markets showed no signs of abating, more funds began to embrace direct private equity investment, attracted by annualized returns that hovered around 16%. As the economic recovery gathered momentum, starting around 2013, these and other funds looked for opportunities to reduce the fees charged by private equity funds, prompting many to become more directly engaged. The result: the average private equity portfolio stake has more than tripled, growing from 4% in 2000 to 14% in 2016.

The move to private equity investment has given principal investors an opportunity to boost returns, put excess liquidity to work, achieve greater geographical diversity, and deploy capital beyond their domestic markets. But with those higher returns comes a greater need to preserve value—and that requires changes in the way funds have traditionally been managed.

Four Direct Investment Models

Private equity investment gives principal investors an opportunity to boost returns, put excess liquidity to work, achieve greater geographical diversity, and deploy capital beyond their domestic markets. But there are different ways to go about it. Principal investors can choose to invest directly, co-invest with others, and invest indirectly through funds.

Of these options, going direct has the potential to deliver the greatest long-term value. One principal investor we spoke with noted, “Going direct reduces fees and allows us to align the asset strategy with our longer-term investment horizon, as opposed to the mid-term approach of GPs [general partners] in private equity funds.” As a result, we see more principal investors choosing to pursue direct investment over indirect and co-investment approaches.

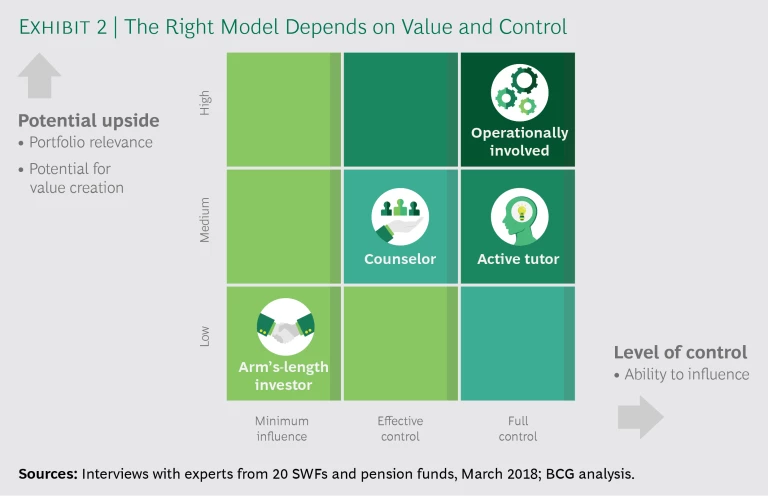

Direct investment, however, comes in different flavors, depending on how involved a firm wants to be, the level of impact it hopes to make, and the amount of control their investment gives them. Broadly speaking, there are four major direct investment models.

- Arm’s-Length Investor. Under this model, principal investors provide high-level strategic guidance to company management through their board representatives but refrain from direct decision making. This model is the least resource-intensive in terms of team involvement and can be a good way for investors new to active private equity deals to get started.

- Counselor. Under this model, principal investors take on the role of trusted advisor, working with the board and senior management to develop value creation plans and provide guidance on a range of governance matters. In some areas, such as board selection, remuneration, and governance, they take on a more active decision-making role while maintaining an advisory role in most other areas.

- Active Tutor. In this model, principal investors serve as a key in-house resource for company management, providing ongoing decision-making guidance on a range of matters including governance, financial management, strategy, and operations, as well as helping management source key staff positions.

- Operationally Involved. This is the most hands-on model. Here principal investors play a significant decision-making role in nearly every facet of the business. That includes helping to define long-term strategy and providing operations insights and support. They also often take the lead on helping the company implement the recommendations provided. This model is the most time- and cost-intensive and requires that the principal investor build a dedicated and experienced team within its own firm to manage the relationship.

When selecting which model to use, consider that, all other things being equal, the more active and involved the principal investor is, the more value will emerge. But that involvement comes at a price. There are certain conditions that must be met in a cost-effective way for investors to protect and grow value. (See Exhibit 2.)

The first is capacity. Principal investors need to assess whether they have sufficient internal expertise to engage actively—and, if so, at what level, since the more involved investors become, the more operational support and industry knowledge will be required.

The second is scale. Principal investors need to determine if they have a large enough asset concentration in relevant sectors to amortize the cost of the experienced (and expensive) talent they will need to adequately manage their direct private equity investments.

Third, principal investors must ensure that they have a sizeable enough investment stake at the individual asset level to secure board representation and have a voice at the table.

Fourth, for their strategy and approach to succeed, investors need to assess whether the total value creation potential can deliver returns in line with or above their investment thesis.

Finally, investors should streamline the logistical factors. One investor we interviewed said, “For international assets, having the senior investment manager flying in all the time for multiple board meetings is inefficient and unsustainable.” Funds need to take into account geographic distance, the type of expertise needed, and the investment fit within the firm’s internal capabilities and legal restrictions.

All of these conditions will demand a substantial shift in strategy and resources, and principal investors ultimately must determine if they can justify that, especially given the long-term nature of SWF, pension fund, and family office investments.

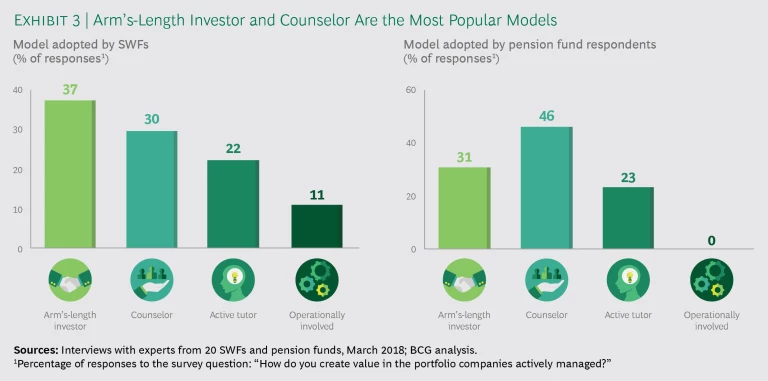

For these reasons and because direct investment remains a relatively new approach for principal investors, most people we surveyed said they opt for modest levels of engagement: 67% of SWFs and 77% of pension funds use the arm’s-length model or counselor model; 22% of SWFs and 23% of pension funds use the active tutor approach. By contrast, only 11% of SWFs and 0% of pension funds take an operationally involved role. (See Exhibit 3.) Limiting direct engagement makes sense initially, given the resource investment and internal changes required.

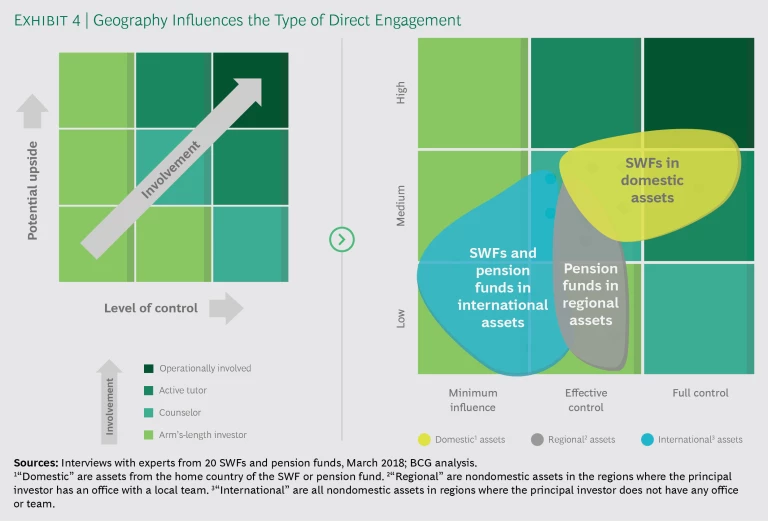

Of the respondents who indicated they use the operationally involved model, all were SWFs and the investments in question were all domestic. Many SWFs have a mandate to maximize national economic impact, so they typically take a majority stake in their domestic investments and stay closely involved in the company. None of the pension funds in our study use the operationally involved model, although pension funds that maintain local offices outside their home countries are more open to taking on a significant majority position and a counselor or active tutor role, since their regional presence enables more hands-on engagement.

SWFs and pension funds with investments in international assets are far more likely to take an arm’s-length approach, given the challenge that geographical distance poses to direct engagement. Funds diversifying abroad, for instance, typically invest in a minority position and generally prefer low exposure to avoid any negative impact on their reputations if something goes awry. (See Exhibit 4.)

Changes in Fund Governance and Organization

Our survey indicates that, apart from selecting the appropriate direct investment model, principal investors need to consider new ways of governing funds and to establish stronger organizational supports.

Determine Proper Governance

How principal investors manage the process of forming an investment thesis, selecting board representatives, and engaging with the board can vary, but it is critical to think through these factors at the outset in order to succeed with direct investing.

Providing investment and portfolio management teams with adequate autonomy, ensuring competitive compensation practices, and clarifying and codifying governance guidelines play a significant role in enabling direct investment in private equity. When principal investors don’t do that, they are often limited in how direct and engaged they can become. For example, many Canadian pension plans and Middle Eastern SWFs give managers adequate autonomy and budget to recruit large direct investment teams. Other organizations, however, notably US pension plans, have not done that, which has hindered their ability to attract suitable talent.

Principal investors should consider the following elements when designing their governance program.

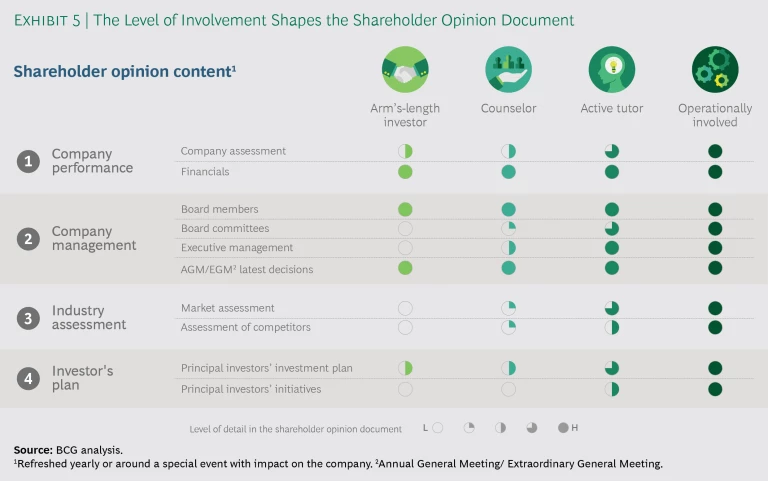

Shareholder Opinion and the Investment Thesis. This includes an assessment of the portfolio company and development of the investor’s view in order to help communicate the investment objectives to all stakeholders. The amount of detail provided in the shareholder opinion document depends on the level of principal investor involvement, with operationally involved investors providing the most extensive information. (See Exhibit 5.)

Board Representative Selection. Most principal investors (87%) surveyed said they prefer to have direct representation on the board to improve communication and oversight. Direct representation also helps by removing the need for other types of structured engagement between the board representative and the principal investor’s internal teams. One principal investor we interviewed said, “Appointing the most senior member of the deal’s investment team to the board is key to ensuring that the investment thesis is reflected in the asset.”

Many of those we spoke with also said that it’s important to complement internal board representatives with independent, external directors, for three main reasons: it allows access to deeper industry experience, especially when the asset needs significant hands-on involvement; it augments internal resources, especially when the principal investor is entitled to multiple board seats; and it improves the perception of independence when becoming active has reputational risks. As one principal investor noted, “For larger stakes, multiple board representatives are required, at least one of whom should be internal to the firm. The remainder should be external directors who have significant experience in the sector.” Another added that the firm should “prioritize the appointment of external board representatives because it is critical to increase the public perception of independence.”

According to survey responses, principal investors that pursue the arm’s-length investor or counselor model tend to have minimal influence and are usually accorded an average of one board seat (zero in some arm’s-length investor cases), which they may choose to fill from within their internal ranks or with an outside director. The amount of industry experience required of directors ranges from 0 to 5 years to more than 15 years, commensurate with the size of the stake and degree of involvement in day-to-day operations and decision making.

Board Engagement. Principal investor portfolio management teams need to engage with the board to support ongoing communication and reflect shareholder priorities. One Southeast Asian SWF has adopted a structured engagement process for its direct investment activity. They select external board representatives to ensure independence. Before each board meeting, the investment team prepares an in-depth analysis of the topics that will be discussed, which it shared with the outside directors. If the board’s relationship with the fund is relatively new, the fund’s investment team prepares a formal document with voting guidelines. Otherwise, where the relationships are well-established, the guidelines are communicated verbally. Also before the board meeting, the investment team and the fund’s board representatives meet face-to-face to review the package, voting guidelines, and any other materials. Then, when the board meets, the fund usually has a board observer in place to report on the meeting outcomes; if no observer is present, a call between the investment team and the board representative is arranged following the meeting.

As the level of involvement increases, our survey found that principal investor board engagement becomes more structured. For active tutor and operationally involved models, principal investors are more likely to institute a formal engagement and consultation process, whereas those that pursue an arm’s-length investor model are more likely to arrange engagement and consultation upon the board representative’s request. Independent directors on the board are likely to be more involved and to participate in a more structured way.

Roles and Accountability. To improve both governance and the potential for value creation, principal investors should define clear roles for the investment team, the portfolio management team, and board representatives. To that end, we recommend several best practices.

- The investment team should be responsible for analyzing the required topics in the formal board package and for working with the portfolio management team to consolidate recommendations. This will ensure an informed view that supports the investment thesis.

- The portfolio management team should be responsible for receiving the board package and analyzing required topics, consolidating recommendations, and then arranging a meeting with board representatives before the board meets to discuss voting guidelines. Where possible, the portfolio management team should attend the board meeting as board observers. After the meeting, the principal investor team should gather to review critical topics discussed and plan relevant action.

- Board representatives should contribute to the board materials and participate in the pre-board meeting to discuss voting guidelines. They are responsible for attending the board meeting and for preparing the report, if one is needed, and they should be consulted in post-meeting discussions on relevant topics.

Establish the Right Organizational Structure

Direct private equity investments require strong organizational supports. For example, we’re finding that as principal investors (especially pension funds) increase their level of direct investment, many are creating portfolio management teams to work with their investment team.

Because portfolio management teams bring deeper sector, functional, and operational expertise, their involvement can be crucial in helping principal investors attend to the significant responsibilities involved with active management. As one principal investor told us, “The portfolio team was critical in helping us look for synergies across the portfolio.” Another said, “The investment team should always work with the portfolio team in managing the assets. That’s the only way the investment team can stay accountable for asset performance.”

Building a strong portfolio management team, however, comes with challenges. In the context of becoming more active, principal investors need a bench of talent with specialist expertise. The level and quality of that in-house knowledge can determine how actively funds invest in private equity. Under the arm’s-length investor model, for instance, funds need substantially less industry and business-specific knowledge to engage with an asset than funds that pursue the active tutor or operationally involved models.

In our survey, 72% of respondents told us that developing internal capabilities was their biggest challenge in engaging in direct private equity. Principal investors not only need experienced talent; they also need to ensure they have enough volume to keep their talent busy. One principal investor told us, “Developing internal capabilities at the right cost is a significant barrier to funds interested in becoming more active.”

To address these issues, 54% of principal investors say they outsource sector expertise and 46% outsource operational expertise. Some are also restructuring roles and responsibilities within their portfolio and investment teams. One Canadian pension fund established a dedicated portfolio management team with a mix of industry and consulting backgrounds to support the firm’s private equity team. From a budgetary standpoint, the firm apportioned roughly 10% of total available resources to the portfolio management team and allocated the remainder to its investment team. The firm gave the portfolio management team responsibility for defining and updating the value creation plan and for assigning ownership of those initiatives. The portfolio management team assigned itself the more complex initiatives, while the investment team or the company itself took care of less complex initiatives. This ensured that the portfolio management team’s time was spent on cases requiring the most expertise and care.

Getting Started

As principal investors work to engage more actively in private equity, the following six steps can serve as a useful guide.

- Decide if direct investment makes sense. The answer requires thinking through whether the principal investor has the investment capabilities to source direct deals in those sectors and if the direct sourcing costs are lower than paying the funds’ fees and carry.

- Clarify the overall objective. Consider whether the principal investor has a mandate to increase the asset value in its direct private equity investments and whether the ultimate purpose of going direct is to save fees or become involved in the asset.

- Select the engagement model (arm’s-length investor, counselor, active tutor, or operationally involved). Determine if the principal investor has the capabilities to engage on its own or if it should go with an operating partner.

- Establish the governance framework. Consider whether the investment team has free capacity to appoint a member as a board representative, and determine whether the principal investor wants to control all board-voting decisions or fully delegate that to the board representatives.

- Develop or update the shareholder opinion based on the investment thesis. Clarify the principal investor’s expectation for the asset based on the investment thesis, and consider if the investment size merits laying out a formal shareholder opinion.

- Reassess the engagement results regularly to refine objectives as needed. Ask whether the chosen engagement model led to the desired improvements in the asset in line with the shareholder opinion and if the principal investor should reduce, maintain, or increase its involvement.

Looking Ahead

Over the next several years, we expect that the shift in principal investing toward direct channels will change the investment landscape significantly. As a result, we envision three potential scenarios for the active management of direct private equity investment.

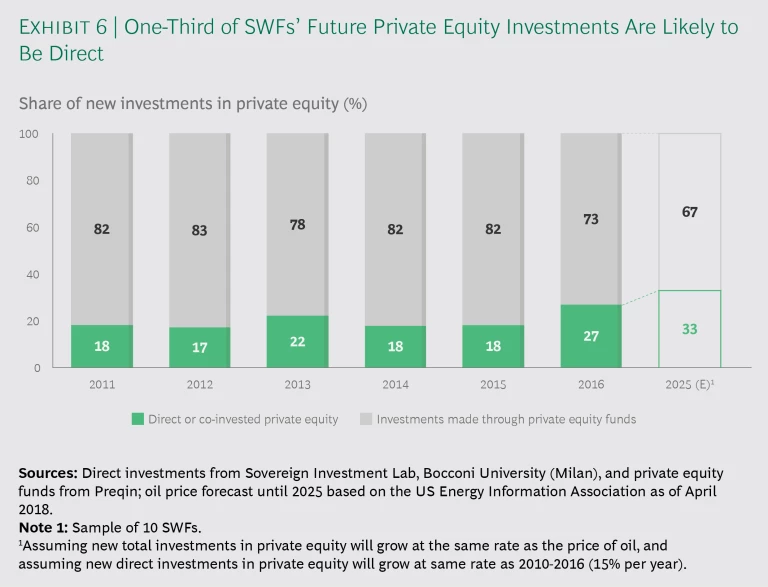

Principal investors will increase direct exposure. We believe that the prospect of lower fees and the ability to deploy significant liquidity as well as increase control over portfolios will continue to attract principal investors to direct private equity. While average private equity returns are expected to fall from 16% to 10% from 2016 to 2020, those yields are still better than other options. Public equities are likely to remain volatile, and fixed income is expected to remain below target. Unlike these two options, private equity investments are generally not marked to market, limiting short-term volatility.

We believe that SWFs’ share of direct private equity will eventually account for about one-third of all new private equity investments. (See Exhibit 6.) As they and pension funds grow their active investments, some may seek other approaches. One Canadian pension fund announced in 2017, for instance, that it was considering funding its own private equity investments and assessing the potential of setting up a separate vehicle for private equity deals. Doing so would allow it to address criticisms over high fund fees and limited disclosures. In addition, by leveraging its existing co-investment program, the fund could access needed private equity expertise to go direct. The fund would also establish “no fly zones” to ensure that target opportunities did not compete with current private equity investments.

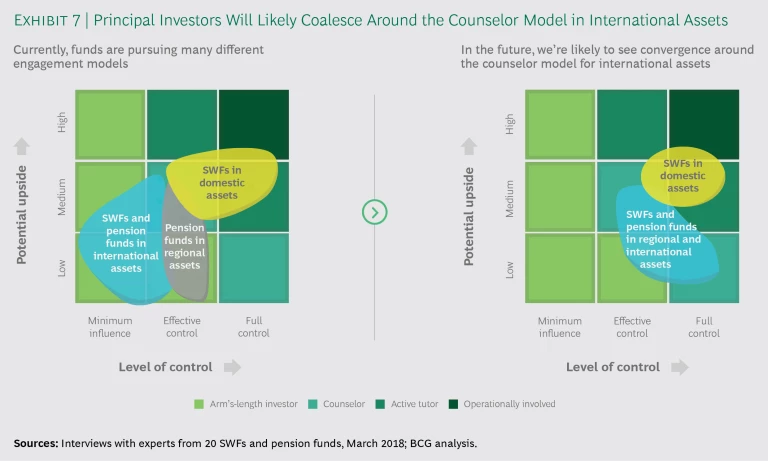

Principal investors will use the counselor model for international assets. The active management approach for most principal investors is likely to plateau in international assets. Skilled resources are hard to find and expensive to hire. To secure additional required capabilities, investors will need significant scale in direct private equity. Therefore, we believe principal investors will likely converge around a counselor model in which they will reassess whether active management can deliver the promised value creation. (See Exhibit 7.) They will also reassess the tradeoff between building an in-house team versus co-investing or investing in funds that demonstrate best-in-class capabilities. Larger funds will likely create more value by building in-house teams, and many have the scale to fund such a change. Principal investors will also need to reassess what it would take to move up to becoming more operationally involved in order to generate additional value.

Private equity firms will reassess their overall business models. We believe that private equity firms will explore new revenue streams and models as principal investors go more direct or seek co-investment opportunities. Increasing competition and price pressure will require changes in fee structure and the service offering as a whole. Principal investors will begin to encroach on the private equity space in search of higher returns and lower or no fees. The immediate availability of funds gives principal investors faster access to deals. As a result, private equity funds will push the boundaries of their service offering and provide principal investors with expanded advistory services. One large investment bank, for instance, recently created a dedicated direct and co-investment group to advise institutional investors in deal origination, structuring, and negotiation and help principal investors enter new industries and sectors directly. Private equity players will also become more open to co-investments with principal investors to strengthen relationships and de-risk capital commitments. Private equity funds will begin to complement their current offering with longer tenure, lower risk, and lower fee options in order to remain an attractive value proposition for principal investors.

A major Canadian pension fund, for instance, announced that it would join a new private equity fund that targeted 15% returns instead of the usual 20% returns. The lower returns would be offset by lower fees, a longer investment period (of up to 12 years), and lower risk, since the targeted assets would reliably generate cash.

Similarly, the private equity fund of a large asset manager announced the formation of a direct and co-investment group with the goal of providing advisory services to principal investors as they move to direct investing. By advising on deal origination, structuring, and negotiation, the group hopes to help principal investors improve returns and give them the insights they need to enter new industries and segments.

With principal investors concentrating a greater share of their portfolios into private equity, how they manage those investments will have a significant bearing on overall fund performance. Not only is there more than one way to go direct, each comes with very different governance, operational, and cost considerations. For principal investors to squeeze the most value from their private equity holdings, they need to up their game and approach direct investment in a more sophisticated fashion.