In 1602, commerce evolved into capitalism when the Dutch East India Company formally syndicated its ownership. The first dispute between managers and shareholders came shortly thereafter, in 1622, when a “complaining participant” sued for control rights, citing disagreements on transparency, governance, and capital allocation. Throughout the next four centuries, company owners and managers have wrestled with how best to handle the inherent tensions between long-term shareholder value creation and myriad other management objectives.

BCG has been advising companies on value creation since our founder, Bruce Henderson, opened its doors more than five decades ago. Indeed, many of the firm’s innovations—such as the growth share matrix, experience curves, and cash trap—stem from our early work on the ways that competitive advantage and capital allocation interact to create value for a company’s owners.

In 1998, the firm published the first BCG Value Creators Report, which ranked the top corporations on the basis of the value they’d created over the previous five years and also attempted to draw out lessons from the winners. Since then, we have expanded our databases, refined our methodologies, and—continually developing our thinking—shared our perspectives annually. For our 20th report, we have now diligently reassessed our cumulative experience and distilled our perspectives down to ten lessons—including the source of some of the most common managerial mistakes—that we think really matter. (See “Value Creation Insights Through the Years”)

Value Creation Insights Through the Years

Value Creation Insights Through the Years

- The 2017 Value Creators Report: Disruption and Reinvention in Value Creation

- The 2016 Value Creators Report: Creating Value Through Active Portfolio Management

- The 2015 Value Creators Report: Value Creation for the Rest of Us

- The 2014 Value Creators Report: Turnaround

- The 2013 Value Creators Report: Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation

- The 2012 Value Creators Report: Strategies for Superior Value Creation

- The 2011 Value Creators Report: Risky Business

- The 2010 Value Creators Report: Threading the Needle

- The 2009 Value Creators Report: Lessons from Consistent Value Creators in the Consumer Industry

- The 2008 Value Creators Report: Missing Link

- The 2007 Value Creators Report: Avoiding the Cash Trap

- The 2006 Value Creators Report: Spotlight on Growth

- The 2005 Value Creators Report: Balancing Act

- The 2004 Value Creators Report: The Next Frontier

- The 2003 Value Creators Report: Back to Fundamentals

- The 2002 Value Creators Report: Succeed in Uncertain Times

- The 2001 Value Creators Report: Dealing with Investors’ Expectations

- The 2000 Value Creators Report: New Perspectives on Value Creation

- The Value Creators Report: A Study of the World’s Top Performers

1. Value creation is not the only goal, but it is essential. The concept of shareholder value incites lots of debate. For some, it is the singular company objective. For others, it is a misguided target. There are plenty of points of view in between.

This debate sucks up a lot of air purposelessly, for two reasons. First, companies have shareholders, shareholders have rights, and shareholders are increasingly sophisticated, exercising their rights through activism and other channels. More often than not, a management team that loses the support of its investors also loses control of the company’s agenda, including the ability to pursue other, nonfinancial objectives.

Second, the conflicts among the differing points of view are not as intense as many believe them to be. There is a growing body of evidence that purpose-driven, sustainable strategies are also beneficial to shareholders. Our research on the impact of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics shows that companies that perform well in terms of nonfinancial ESG measures also deliver better financial performance and command measurably higher valuation. (See Total Societal Impact: A New Lens for Strategy, BCG report, October 2017.)

Put another way, building a great company is not at all inconsistent with being a great stock.

2. Metrics alone are not enough to achieve this goal. Here are two points that they don’t teach in business school.

First, the theory that value creation comes solely from the act of making positive net present-value investments is of limited use in most modern public companies. Fundamentally, investors price a company’s shares on the basis of their views of the underlying business and the attractiveness of the available reinvestment opportunities. Because such expectations are priced into the stock today, the real value creation task confronting leaders of public companies is the need to make more and better investments than the ones already anticipated by investors or to increase—beyond expectations—the profits being earned on existing investments. Beating expectations as expectations evolve is what matters. It’s no small task, and it’s nearly impossible to achieve using metrics alone.

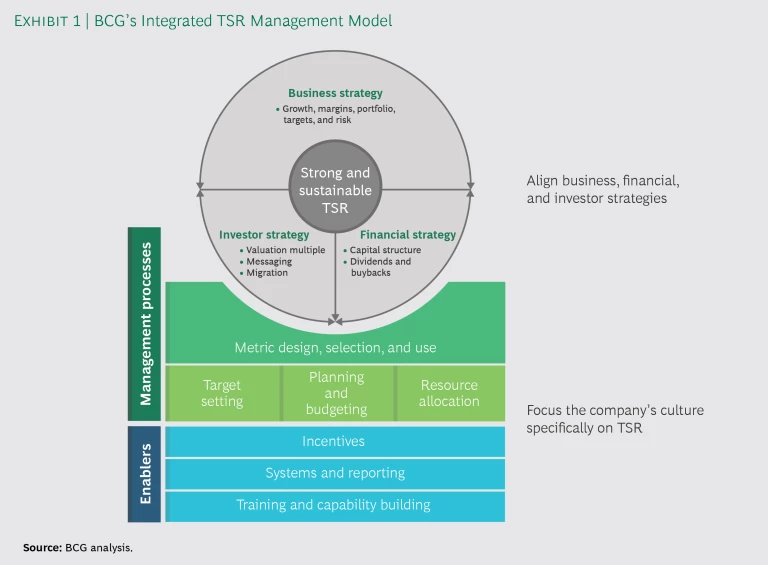

Second, strong and sustainable value creation is delivered in the trenches. Hardwiring value management principles into an organization’s systems and processes—including target setting, planning, capital allocation and risk assessment performance reviews, and incentive compensation—is just as important as getting the metrics right. (See Exhibit 1.) A comprehensive value creation agenda encompasses both the hard (performance) and soft (culture) sides of the challenge. (See “VF Corporation’s TSR-Led Transformation,” BCG article, September 2013.)

3. Medium-term TSR must be the capstone metric. Two truths are critical to understanding many of the common mistakes made in the name of value creation: TSR is the only metric that represents the shareholder’s bottom line, and the only metric that correlates 100% with TSR is TSR. (See “Value Creation and Corporate Reinvention,” BCG article, December 2017.) Medium-term TSR, measured over a three- to five-year time frame, gives strategies the chance to be implemented and investments the opportunity to mature.

Substituting any proxy metric for TSR inevitably leads companies off course. When earnings per share (EPS) is the principle governing metric, for example, managers can end up “buying” increased EPS by cutting important investments such as R&D or making excessive capital expenditures, ill-advised M&A moves, or poorly timed buybacks. In contrast, TSR is balanced, and it takes into account all the critical factors that drive fundamental value: revenue growth (from reinvestment in the business), margin expansion (from cost control and pricing), and cash flows (which can be reinvested in more growth or used for debt reduction, dividends, and buybacks). TSR also takes into account how managerial actions that determine the valuation multiple, such as investing in the future, optimally deploying capital, or reducing risk exposures, affect investor expectations.

The only metric that correlates 100% with TSR is TSR.

Medium-term TSR is the only performance metric that appropriately scores the game. This is why it is the only multiperiod metric mandated by the US Securities and Exchange Commission and why it’s the principle performance metric evaluated by Institutional Shareholder Services. These two bodies exert outsize influence on corporate reporting and governance around the world.

4. Every company can find a path to value creation. Managers often feel trapped, or at least typecast, by industry expectations and macroeconomic factors. They overlook the inevitability that in every industry and for every cycle, there are winners—companies that outperform the pack.

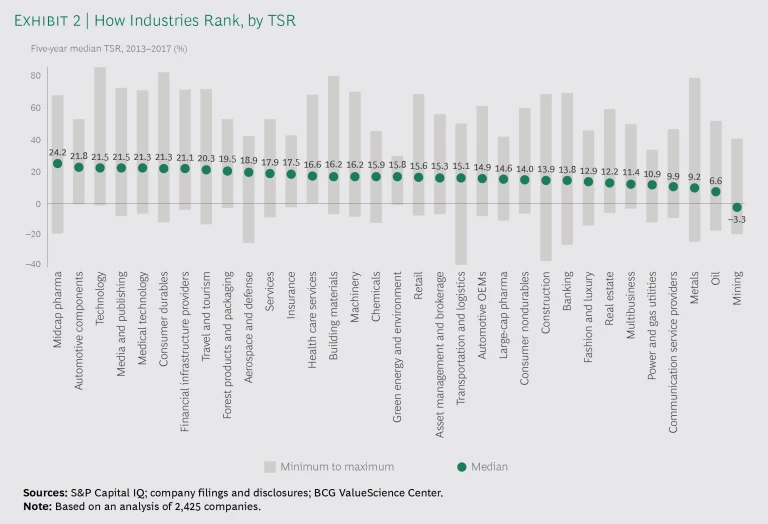

Starting points matter, but for almost every starting point, there is a value-creating road forward. As always, in 2018, the leading companies in our sample of top value creators substantially outpaced their own industry as well as the total market. The median TSR of the top ten companies in each industry was higher than the industry’s median by 9 percentage points (in insurance) and 32 percentage points (in media and publishing as well as metals). (See Exhibit 2.)

The lesson is this: being in a sector whose market performance is below average is no excuse. TSR is a relative—as well as an absolute—metric, so whether an industry is under pressure or accelerating, every company has the opportunity to outperform its peers. No matter how bad an industry’s average performance is relative to other sectors and to the market as a whole, it is still possible for companies in that industry to deliver superior shareholder returns. (See “How Top Value Creators Outpace the Market—for Decades,” BCG article, July 2017.)

5. Growth is the most common path to TSR outperformance, but not the only path. Profitable revenue growth is often the primary driver of TSR outperformance over extended time horizons. For top performers during five- to ten-year periods, revenue growth accounts for an average of 50% to 70% of value creation. For this reason, it’s easy to forgive managers for concluding that growth is all that matters.

Still, this view is misguided for two reasons. First, it overlooks that myopic pursuit of growth is one of the most common paths to value destruction. (See Threading the Needle: Value Creation in a Low-Growth Economy, the 2010 BCG Value Creators Report, September 2010.) Aggressive growth can be a high-risk, high-reward proposition, and “bad” growth is a common cause of long-term TSR underperformance. There are many examples of companies that were able to sustain 10% or more top-line growth only to generate below-average or even negative TSR. In many cases, such disconnect is driven by M&A moves gone bad, prioritizing growth at the expense of margins, betting on a cycle that collapses, or investing in adjacencies in which the competitive advantages of the core business do not apply.

The second reason is that there are many examples of top-quartile value creators generating TSR from some combination of other factors, including margin improvement, cash return, and multiple expansion. Our 2017 list of the top consistent value creators over 20 years contained two tobacco companies, which, despite shrinking markets, adverse regulation, and ample brand disparagement, generated annual TSRs of 17% and 22% from 1997 through 2016.

There are many paths to top-quartile TSR.

6. Cash flow is underappreciated and often misunderstood. While growth is the most common route to top- and bottom-quartile performance, it is cash that accounts for most of the shareholder return that a company generates over time. Indeed, since 1926, about 40% of the TSR of the S&P 500 has come from cash returned through dividends—even more when buybacks are factored in. Furthermore, cash generation is the main driver for growth businesses, as it defines the magnitude of a company’s organic or M&A long-term reinvestment rate.

Beyond the simple truth that cash flow is king lies a less obvious point: investors do not value equally all dollars returned to shareholders. In fact, the method of return—share buybacks, dividends, or debt repayment—can have a powerful secondary effect on valuation. For 15 years, we have been arguing in our publications that dividends are especially important: material increases in payout often lead to a significant expansion of a company’s valuation multiple and therefore, in the right circumstances, can drive far greater TSR than buybacks. (See “Thinking Differently about Dividends,” BCG Perspectives, May 2003.)

7. M&A is a powerful tool—for those that commit to it. M&A has a bad rap, thanks to the commonly cited assertion that most deals destroy value. It is true that more than 50% of deals simply transfer wealth from buyer to seller. But there is an untold other side to that story: many long-term, top-quartile value creators engage in significant numbers of M&A deals. (See The 2015 M&A Report, BCG report, October 2015.) This should not be surprising: M&A is one way (and there are not that many others) to reinvest large amounts of capital. Furthermore, well-sourced and well-executed deals can serve up substantial returns. (See “The Real Deal on M&A, Synergies, and Value,” BCG article, November 2016.)

The factors that make successful acquirers successful are straightforward. These acquirers commit to M&A and approach it as they would any other industrial process: they climb an experience curve, become proficient over time, and scale up their capability. They also invest disproportionately in three key areas. (See “Lessons from Successful Serial Acquirers,” BCG Perspectives, October 2014.) First, they craft a proprietary view of the ways that they create value. This guides their M&A strategy. Second, senior leadership is deeply engaged in the M&A process, and managers at all levels of the organization are expected to source and cultivate relationships with potential targets. Finally, the most successful acquirers articulate a core set of operating principles that define the way that the M&A process will be managed with no additional bureaucracy.

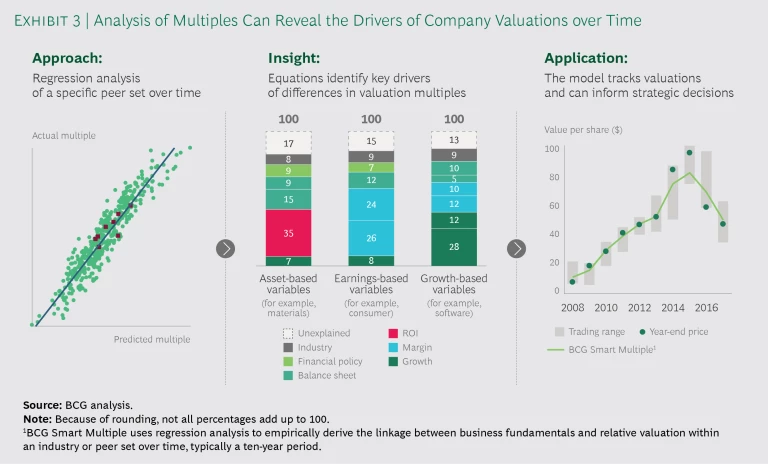

8. Valuation multiples are no longer a black box. In many cases, managers think that a company’s valuation multiple is a random and uncontrollable outcome and that fickle investors don’t truly understand the businesses in which they invest. We respectfully disagree. While multiples move somewhat randomly over short time periods as they incorporate a wide range of information about future profits and risk, they are not random and certainly not uncontrollable. We have invested more than 20 years in building an analytical tool set that helps companies understand how their shares trade in public markets and which financial KPIs investors take as signals of a healthy (or unhealthy) business outlook. Our tools reveal the key drivers of valuation, which, in turn, can reveal strategic information about a business. (See Exhibit 3.)

Our tools reveal the key drivers of valuation, which, in turn, can reveal strategic information about a business.

One can point to countless examples. In many industries, investors look at gross margin as a proxy for a business’s resistance to commoditization (in, for example, technology) or its brand power (apparel). Investors in financial services put a premium on return on tangible equity. Biotech investors value forward-growth expectations—almost without regard to current profitability. In other sectors, investors put a premium on dividends, which they view as signals of a company’s confidence in future earnings and its managers’ willingness to put their money where their mouth is.

The drivers of valuation provide a rich and refined tool for common managerial tradeoffs, such as driving growth at the expense of margins or reinvesting free cash flow instead of paying down debt. Indeed, the success of companies such as Church & Dwight and VF has been achieved, in part, on a strong understanding of the way that business fundamentals and valuation multiples interact to inform strategic decisions. (See Improving the Odds: Strategies for Superior Value Creation, the 2012 BCG Value Creators Report, September 2012.)

9. The shape and asymmetry of investment opportunities are far more important than the precision of the calculations behind them. Too often, senior management wastes time and energy trying to get the data inputs for their models precisely right. The leading example of this phenomenon is the fruitless fretting over a company’s weighted average cost of capital. (Charlie Munger, the vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, once said, “I’ve never heard an intelligent discussion about the cost of capital.” He’s right.) What managers should be evaluating is how a proposed investment compares with the next-best use of capital. If the difference in the cost of capital assumptions (within reasonable bounds) reduces the attractiveness of an investment, it has likely already failed the test.

Even more important, excessive focus on technical precision takes time and effort away from the more meaningful determinants of investment decisions, such as the reliability and asymmetry of the forecast and whether there are any accounting principles at play that decouple reported earnings from cash flow. Management time and attention are much better spent on pressure-testing key assumptions, contrasting different approaches for evaluation (such as cash versus accounting metrics), and considering the different competitive scenarios in which the investment could unfold. (See Risky Business: Value Creation in a Volatile Economy, the 2011 BCG Value Creators Report, September 2011.)

10. Treating your investors like customers pays dividends over time. Relatively few companies put anywhere near the level of time, effort, and intensity into learning why investors own their stock that they put into figuring out why customers buy their products. This is a mistake.

Some customers are more valuable than others, so it makes no sense to try to serve every customer equally. Similarly, there are investors that a company wants and those that it would just as soon not have. Each investor has its own investment process, capital allocation preferences, KPIs, and buy-sell triggers. Investors differ in their willingness to support a company’s mid-to-long-term strategy—especially when results are likely to take time to materialize. The smart play for management teams is to identify the “right” investors and go after them, just as they would pursue high-value customers.

Doing so takes more than the typical approach to investor relations. Value-oriented leadership teams seek to engage in a genuine dialogue with sophisticated investors about the ways value will be created. They use such opportunities to benefit from the experience of portfolio managers and analysts, whose insights can help challenge conventional wisdom within the company.

Company executives also need to appreciate that the support of patient and long-term-oriented investors comes at a price—in the form sometimes of inconvenient transparency. During both good and not-so-good times, investors want a candid assessment of key market forces, the company’s strategies to win, and the upsides for sticking around, as well as the roadmap for getting to the payoff and how they can track progress. And when mistakes are made, investors want to know what lessons have been learned. They increasingly also want reassurance that a solid governance system—one that includes a proven board of directors and executive compensation that emphasizes the right metrics—is in place. (See Winning Moves in the Age of Shareholder Activism, BCG Focus, August 2015.)

All this takes time and sophistication on the part of management, but the effort is worthwhile. Over and over, we see that well-aligned investors are critical to ensuring the success of well-designed strategies.

The shape of the playing field has changed many times since the early 17th century and, indeed, over the 20 years of our Value Creators series, which have seen the dot-com bubble expand and burst, the surges in the middle years of the first and second decades of this century, and the great financial crisis. One of the biggest changes has been to the nature of business itself.

Value management grew up in an economy that was dominated by capital-intensive companies, for which value creation was largely about squeezing out incremental returns on physical capital (accounted for on balance sheets). Recent decades have seen the rapid rise of “discovery” businesses—including IT, pharma, professional services, and medical technology—for which value creation is much more about driving top-line growth and generating returns from investments that flow through the income statement. (See “Value Patterns: The Concept,” BCG Perspectives, May 2012.)

This proliferation of new business models is, in many cases, interpreted as making value management less relevant when, of course, the opposite is true. The 2019 Value Creators report will examine some of the new challenges we expect managers to face as advancing technology causes the economy—and the managerial principles that govern value creation within it—to evolve. But the use of TSR as a North Star that guides value-creating agendas and the application of the hard-won, timeless principles of value creation are more important than ever. The game may be changing once again, but the rules—and the ways of winning—remain the same.