For most established grocers, private-label products are a big component of revenue—but not as big as they could be. And because these products are offered in addition to a huge range of branded goods, they create complexity at each step of the supply chain.

We believe established grocers need to rethink their strategy for private-label products. By developing true retailer brands that can compete with—and often beat—established CPG offerings, grocers can differentiate themselves from their peers, better engage with their customers, and drive down operating costs across the entire value chain, from production to in-store operations. (A “retailer brand” is a product and label that are developed internally by a grocer, with far better execution than a traditional private-label offering.)

Traditional grocers that don’t differentiate themselves with strong retailer brands risk being left behind.

While this has long been recognized as an opportunity for established grocers, several developments are making it a strategic necessity. One impetus is the rise of value-based grocers, which have grown in part because of strong house brands and extremely efficient value chains, with a much smaller set of SKUs that still meet a majority of most shoppers’ needs. Another is the threat of online commerce. Already, many CPG companies are establishing their own connections to consumers, capturing data and insights and, in some cases, selling directly to them. In this environment, grocers that do not differentiate themselves with a strong set of unique retailer brands risk being outexecuted by value grocers and commoditized by online players.

Growing Threats

Established grocers can see precursors of the threat from value-based competition in other industries, like fashion, and the stories do not end well. Multibrand retailers such as department stores are struggling, and sales growth has shifted to highly efficient branded retailers like Zara, H&M, and Primark. These players have reengineered their supply chains to get their own branded products—and no others—onto store shelves in lead times measured in weeks, thanks to highly efficient distribution networks and stores. Some of them deliver the kind of in-store experience that was previously limited to luxury retailers but at much lower prices. As a result, these lower-cost players have won over customers. They have taken significant share from multibrand retailers, and future growth is on their side.

In the grocery industry, value retailers such as Aldi, Lidl, Mercadona, BIM, and Trader Joe’s are now creating the same challenges for established players. These chains have expanded rapidly in the past decade, in part through robust internal brands. They develop their own products by capitalizing on strong customer insights and efficient, end-to-end value chains.

Value retailers capitalize on strong customer insights and efficient, end-to-end value chains.

Because their products are so popular with consumers, value retailers can carry far fewer SKUs overall—but still meet the needs of most shoppers—leading to simpler supply chains and operating models that give them a huge advantage over other grocers. Store shelves are less cluttered, prices are lower, and the products are as good as—or better than—national CPG brands. For categories such as pasta, chocolate, coffee, orange juice, dish detergent, and toothpaste, value retailers win in head-to-head comparisons with major brands, at prices that are 50% to 75% lower. Further compounding their advantage, some value retailers, such as Aldi, have recently begun selling top national CPG brands, helping them attract brand-conscious customers while still retaining the advantages of a simpler supply chain and operating model.

These grocers have the mindset of a CPG company. They think like a brand and develop products like a brand, yet—similar to fashion players such as Zara and H&M—they control the route to market through their own stores, giving them a huge cost advantage over CPG suppliers. (For some categories, value grocers control the production facility as well. Lidl, for example, manufactures its own ice cream and chocolate.)

By contrast, mainstream grocers have historically developed private-label products for different reasons—to gain marketing power over the CPG brands they carry or to give consumers lower-cost options. Those early offerings from grocers may not have been very high quality, but they were good enough, and because they didn’t require any marketing (essentially riding on the brand of the store itself), they delivered solid margins.

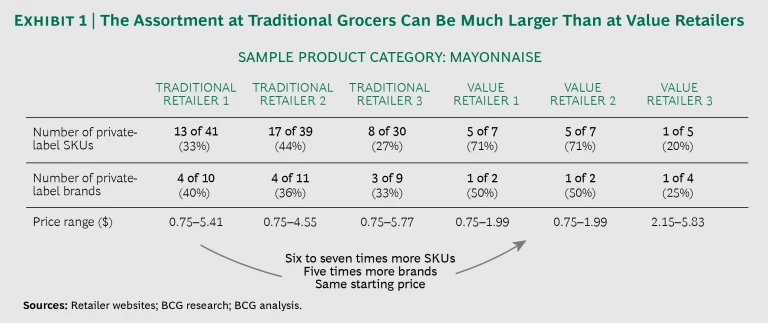

Yet as value retailers have become more sophisticated—with low-priced, high-quality products—traditional grocers have tried to keep up by launching different tiers and lines of their own private-label products: entry-price offerings, along with goods in segments such as kids, organic, and premium. This has led to higher overall sales but also massive assortment sizes and far greater complexity. (See Exhibit 1.) These products lack scale and thus don’t have the margins to justify that complexity. They are the worst of both worlds—they don’t have the brand equity of CPG offerings, and they can’t beat the internal brands sold by value grocers on either price or quality.

The Value in Retailer Brands

The stakes have never been higher, and the potential advantage of retailer brands has never been more apparent. Grocers that get this right can differentiate themselves from their peers by offering products that customers truly want—rather than products they’ll settle for—and that are available only in the grocers’ own stores or on their websites.

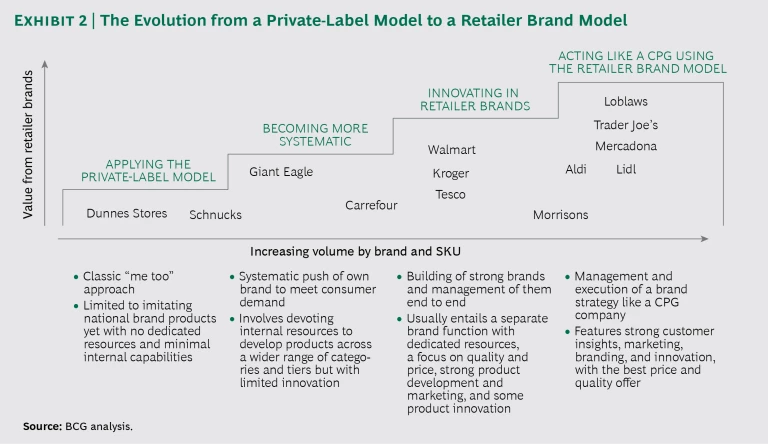

In addition, retailer brands can help grocers become more customer centric and innovative. Many traditional grocers have strong relationships with CPG companies, but they don’t have a deep understanding of their customers. Developing retailer brands requires direct engagement with customers to understand—and meet—their needs. This evolution can lead to increased sales volume, at both a brand and a SKU level, and greater overall value contributed to the bottom line. (See Exhibit 2.) Most important, developing retailer brands can improve customer engagement and loyalty.

How to Get There

For most established grocers, developing a retailer brand strategy will require significant effort and investment focused on several priorities.

Define a clear vision and strategy. The leadership team needs to establish the aspiration for how the private-label business will fit into the organization and—more important—into the overall brand architecture. Grocers can choose from three models:

- The first model (and the historical norm) is to create a single master brand across all product categories with a direct tie to the grocery brand itself. But given how much power brands can have in influencing purchases, this traditional approach is not enough to truly differentiate a grocer from its peers.

- The second model is to develop a set of consumer brands for each category, with a master brand endorsement indicating that the product has been selected by the retailer. E.Leclerc in France is a good example of this model. The chain offers a brand of yogurt that competes with national versions such as Danone but at a much lower price. The only signal to consumers is a small seal of retailer approval on the package.

- The third—and preferred—model is to create a set of brands for individual product categories that function like consumer brands, with no visible tie to the grocer. These products are developed on the basis of direct customer insights that the retailer captures and analyzes, and they feature the right combination of quality and value within their category to make them a credible alternative to existing CPG offerings.

Understand customer needs and build a strong R&D and innovation function. Grocers also need to map and prioritize customer demands so that they can more effectively meet those needs. Innovation is a critical aspect of this process and one where most grocers will need to make dramatic improvements. More broadly, innovation is a means to create excitement among consumers and employees alike, leading to a more dynamic and vibrant store experience. (See the sidebar.)

Four Lessons from Mercadona

Mercadona is the leading grocer in Spain, with a 23% market share and more than 1,500 stores of about 1,600 square meters and 8,000 SKUs each. Over the past 15 years, Mercadona has created a competitive advantage through its private brands. The company’s success offers four clear lessons for other grocers that want to develop strong internal brands.

1. Start with customer needs. Mercadona was one of the first supermarkets to reverse its model from supply driven to demand driven. The company and its employees are obsessed with the needs of the “Boss” (in other words, the customer). The product development process starts with understanding the needs of the Boss, and then the company works with a set of preferred suppliers to optimize all specifications required to develop a winning product. In total, the company introduces 300 new products each week, so store assortments are constantly changing.

2. Develop individual brands for specific categories. Mercadona develops individual brands for product categories such as Deliplus (cosmetics and beauty products), Hacendado (packaged foods), Compy (pet foods), and Bosque Verde (environmentally friendly cleaning supplies). For example, Deliplus overtook L’Oréal in value share after 2011. Deliplus is supported by a dedicated magazine (called La Perfumería), and each store features specialist perfume consultants who advise shoppers and offer value-added services such as gift wrapping.

3. Focus on quality and innovation. To develop innovative and high-quality new products, Mercadona built 13 innovation centers. More than 8,000 customers spend time at Mercadona’s centers each year; they have an opportunity to try products in development under real-world conditions so that the company can understand customer pain points and unmet needs. For example, the center in Valencia focuses on health and beauty products, with a large bathroom and hair salon; another center develops household cleaning supplies. Observers at that center noticed that some homemakers asked for vinegar to clean tile floors. (Vinegar is a traditional cleaning product in Spain.) After gaining this insight, the company developed a winning vinegar-based product for its Bosque Verde line.

4. Create efficiencies at each step of the process. Mercadona brands offer better quality at lower prices because the company manages the product end to end and eliminates any costs that do not add value for the Boss. For example, it avoids unnecessary and non-user-friendly packaging to reduce prices and improve the customer experience. In addition, high sales volume for each product leads to efficient production and competitive purchasing from suppliers and enables the use of a fully automated warehouse, pushing supply chain (and thus overall) costs down substantially.

Establish a clear value proposition for each quality tier or brand. As value grocers have improved their quality standards, the traditional three-tiered structure used by many mainstream chains—one lower-price SKU, one standard, and one premium—is less relevant. Instead, companies need to rethink the value proposition for each of their own brands.

It’s time for mainstream chains to rethink the value proposition for their brands.

The value proposition could vary at a category level—the grocer may keep two tiers for some types of products and consolidate down to a single offering for others. Similarly, grocers may opt to develop category-specific brands—for example, one for fresh food, another for health and beauty, a third for healthy packaged foods. In some cases, a grocer may even opt to buy an existing category brand rather than building it from scratch.

Analyze the organizational changes required. There are various ways to position the retailer brand unit within the organization, depending on the grocer’s maturity level. Companies at the earliest stages of the journey will likely still benefit from having a single, centralized department that is part of the overall buying team but also handles the retailer’s own brands. Retailers that are further along will likely need to set up a dedicated unit within the organization. This structure ensures that the retailer brand team has sufficient power and accountability, can directly access customer insights, and works closely with functions such as marketing, quality, and category management.

Notably, management will need to review and align KPIs and incentives to ensure that the entire organization can move together while still preserving relationships with its CPG suppliers. For example, Migros, a grocery chain in Switzerland that sells primarily its own retailer brands, has a structured incentive system in place that focuses on the value from specific products.

Consolidate and build scale at the level of individual products and brands. To generate and capitalize on their scale, grocers should consolidate sourcing, testing, quality control, packaging and design, and other functions that apply across categories. At each step of the value chain, the grocer can design these product attributes to be as efficient as possible and thus keep prices low. More important, aspects such as packaging can create an emotional connection with consumers and persuade them to pick a product up off the shelf, particularly for new and unfamiliar brands, while generating significant cost savings at all stages of the value chain.

Capitalize on the existing ecosystem. Grocers have several significant advantages over CPG companies. For example, they can give their own branded products prominent shelf and display space. And they can capitalize on their workforce as a de facto marketing team. Most grocery chains have hundreds of thousands of store employees, who serve as the face of the company to customers. By tapping these employees to advocate for retailer brands—and capture consumer insights—grocers can ensure that these products get into the hands and shopping carts of customers. This will be a particularly useful strategy as grocers begin to reduce store complexity, thus freeing up some employees’ time.

Engage with consumers across all media. Most grocers have a traditional means of interacting with consumers, through methods such as weekly coupon inserts. Instead, they need to think like a CPG company and engage with consumers in new ways, across all channels—such as social media. The goal is to get customers excited and create an emotional connection with the retailer’s brands.

Explore partnerships and alliances. Finally, local retailers should explore alliances with other players—through either joint ventures or M&As—in areas such as sourcing and product development. For example, Costco partners with Starbucks for its Kirkland Signature brand. Similarly, for some smaller grocers, it may make sense to collaborate with players in other geographic markets, forming a single organization that can benefit from scale advantages without creating direct competition.

To win in the current environment, traditional grocers need to think and operate more like a CPG company. They can—and, we argue, must—move away from the typical wide range of private-label offerings and consolidate down to fewer SKUs with higher sales volume for the winning retailer brands that remain. Success won’t come easily, but grocers don’t have much choice. They can continue clinging to their established business models and keep losing business to value grocers and online competitors, or they can rethink their approach to brands and set themselves up to win their customers back for good.