The role of specialty chemical distributors has been evolving over the past several years, with major implications across the chemicals value chain. In the past, chemical manufacturers typically viewed specialty distributors as a necessary evil—a means to reach small customers or those that are difficult to serve economically. Today, distributors are becoming a vital component of manufacturers’ channel strategies. The best distributors have deep market insights and the capability to create real value, both for manufacturers and customers. No wonder the market for specialty chemical distribution continues to grow faster than the overall industry.

We recently conducted a comprehensive analysis of the specialty chemical distribution market to identify promising markets and segments and identify trends shaping the industry in the near term. (For similar analyses, see Specialty Chemical Distribution in North America , BCG report, March 2016; and Specialty Chemical Distribution-Market Update , BCG report, April 2014.) The central conclusion of our analysis is that although the market remains extremely attractive, the bar for success among specialty distributors keeps going up.

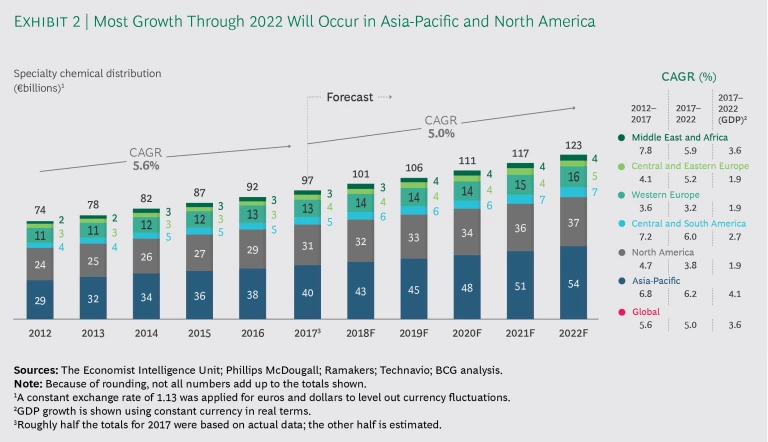

From 2012 through 2017, specialty chemical distribution increased by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.6% each year, to a global market size of about €97 billion. That is faster than growth in the overall GDP (2.7%), the overall chemical industry (2.9%), and specialty chemical consumption (4.9%) during the same time period. To develop a competitive advantage, however, scale alone is not the answer. Instead, specialty distributors need to select specific segments and geographic regions, and then invest in the requisite capabilities that enable them to create value in those segments for both chemical manufacturers and end users.

In addition, digital technology is becoming crucial. It is less disruptive than in other industries because of highly complex technical and logistics requirements, but customers increasingly expect an integrated online-offline experience. Accordingly, specialty chemical distributors must begin to invest in digital solutions, both internally and in customer-facing operations, to amplify their competitive strengths.

Analysis of the Strong Market

The biggest markets as of 2017 were Asia-Pacific (with about €40 billion in specialty distributor sales), North America (€31 billion) and Western Europe (€13 billion). The remaining markets are all less than €5 billion. Asia-Pacific is not only the biggest market for specialty chemical distribution, it is also among the fastest growing, with a CAGR of 6.8% from 2012 through 2017. Only the Middle East grew faster during that period (7.8%). In contrast, most developed markets showed predictably slower growth rates over the past five years: 4.7% in North America and 3.6% in Western Europe.

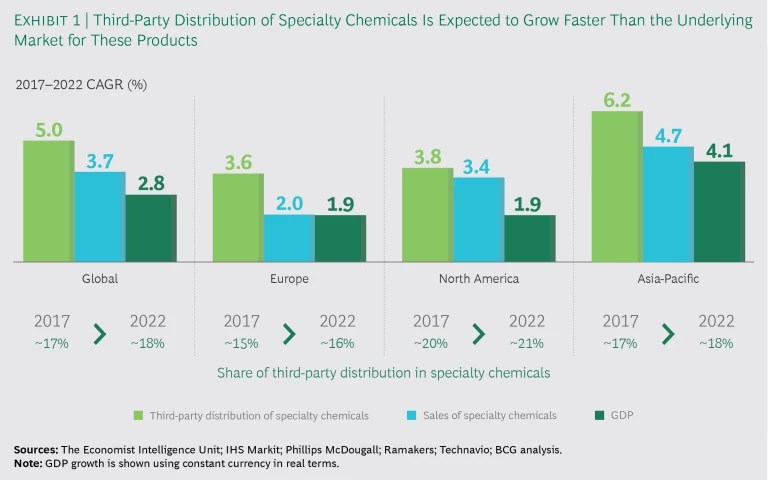

We anticipate that growth in specialty chemical distribution will ease slightly, to 5%, through 2022, due to a slowdown in chemical consumption (for both the overall industry and the subset of specialty chemicals), reduced demand in mature Western markets, and short-term setbacks in China’s economy. However, it will still be faster than GDP growth overall worldwide and sales of specialty chemicals in major markets. (See Exhibit 1.) In absolute terms, most of the growth through 2022 in third-party distribution of specialty chemicals will come from the principal markets of Asia-Pacific and North America. (See Exhibit 2.)

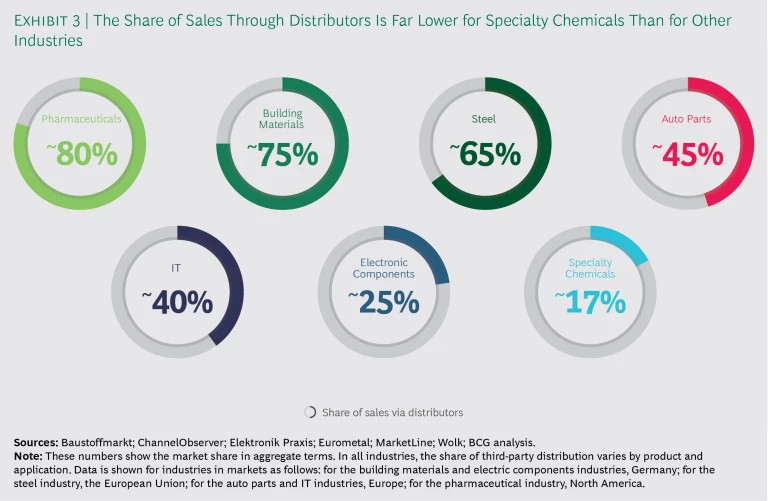

That said, there is clearly room for greater penetration. Distributors still have a relatively low share of the market in absolute terms: only about 17% for specialty chemicals and only 10% to 12% for the overall chemical industry—far lower than in other industries. (See Exhibit 3.)

In the European market, for example, about 40% of IT products and 45% of automotive parts go through external distributors. In the US pharmaceutical industry, more than 80% of finished products go through third-party distributors. In other industries, the characteristics of the products themselves make it more likely that manufacturers will use external distributors, giving them the opportunity for one-stop shopping.

The bottom line of our analysis is that distributors have a significant opportunity to increase their market penetration. There is clear room for growth, thanks in part to shifts in market dynamics in some product segments and geographic markets. (See the sidebar “Seven Trends Underway in the Market.”)

Seven Trends Underway in the Market

Seven Trends Underway in the Market

The chemical distribution industry is undergoing a wave of changes in seven key areas:

- Manufacturers and customers are increasingly seeking to streamline and consolidate their distribution relationships.

- Growing fragmentation among customers—and also in the size and predictability of orders—is generating greater complexity, leading to an increased share of the overall market for third-party distributors.

- Many specialty chemical segments are consolidating on a global level, requiring distributors that serve those segments to expand their reach. The close of a particular M&A deal—and the resulting change of ownership for chemical assets—can be a critical juncture for distributors, as the combined entities also consolidate their distributor base by picking one winner for the new organization.

- Customers are showing a greater demand for value-added services and support, primarily through product development and formulation support.

- Regulatory requirements are growing in the specialty chemical industry.

- Financial transparency is becoming essential. Distributors need to accurately assess the potential of new markets and clearly understand the profitability of individual transactions if they are to improve their gross margins.

- In emerging markets, some industries are maturing, leading to stiffer regulatory requirements and more standardized interactions among manufacturers, distributors, and customers.

But the reasons underlying a manufacturer’s decision to work with a specialty distributor have not changed:

- Manage complexity. Distributors are able to handle sales to small or nonstrategic customers and those that require smaller order sizes. (Some chemical production sites have logistics constraints that prevent them from running small batches or processing small orders.)

- Reach new customers. Distributors can also help manufacturers grow their business by expanding the reach to customers that the manufacturer would not have been able to access on its own.

- Enter new markets. Distributors often have unique insights in a particular region. By working with a distributor, manufacturers can more easily access such a market, particularly if the manufacturer has no current footprint there. The same holds true for product and application segments in which the manufacturer doesn’t yet have an offering but wants to develop one.

- Provide additional services. Distributors provide services that producers can’t or don’t want to provide themselves, enabling tailored go-to-market strategies for different customer segments. These include technical support, formulation services, proprietary compounds, laboratory access, packaging, labeling, regulatory compliance, documentation, and other peripheral services.

Differences by Product Segment and Geographic Region

Even with strong growth prospects, the market for specialty chemical distribution is not a single, homogeneous opportunity. The share of outsourced distribution varies significantly by both segment and region, which presents natural limits to the potential growth of distributors.

Product Segments. Specialty distributors tend to have higher shares in more fragmented chemical categories, where servicing customers entails far more complexity. For example, segments with above-average penetration include coatings and adhesives, construction, and cleaning products (home care and industrial alike). In these segments, there are a lot of relatively small manufacturers selling a huge range of products to a wide variety of relatively small customers, which place relatively small orders. The result is a high degree of complexity, which creates an opportunity for distributors to step in and simplify things for both manufacturers and customers.

At one end of the continuum are segments, such as laboratory chemicals, where customers, such as a university lab, are extremely small and need a wide variety of chemical products delivered regularly. In these segments, specialty distributors can have a market penetration of up to 80%.

At the other end are product categories, such as complex active ingredients for pharmaceuticals, that have a lower share of outsourced distribution. The universe of pharmaceutical manufacturers is fairly small (due to significant barriers to entry), and many players are large, multinational companies that chemical manufacturers can service directly. In addition, some active pharmaceutical ingredients are custom-made by specialty manufacturers for individual customers.

Geographic Regions. The penetration of specialty distributors also varies by region. North America has a higher share (about 20%, compared with 17% worldwide), primarily because of its geographic size. Servicing customers across the North American market requires covering larger distances, which increases the logistics complexity for chemical manufacturers. In Europe, by contrast, distributors have a slightly smaller share (about 15%) due to regional proximity. Manufacturers are able to service customers in a smaller territory, reducing some of the complexity in logistics. Moreover, the universe of distributors is still highly fragmented, reducing the value proposition to manufacturers. In Asia-Pacific, distributor penetration is in line with the global average of about 17%.

Despite being largely similar, each market has some unique characteristics. For example, the distribution market in North America is more mature than in other regions. Distributors have consolidated to a smaller set of highly competent players. Also, manufacturers have professionalized their relationships with distributors. Some have long-term arrangements in place, in which they assign key accounts to specific distributors based on their capabilities, and manufacturers are better able to coordinate relationships with multiple distributors across segments within their product portfolio. These manufacturers have a clear rationale for when they need support from specialty distributors and a strategic approach to interacting with them.

Yet bigger is not always better. Some players—including Brenntag, Univar, and Nexeo Solutions—are the largest in terms of size, but they are not automatically leaders in terms of specialty categories. Super-regionals are beginning to exert more influence, but smaller players still manage to compete. (Notably, IMCD and Azelis are each conducting M&A on both sides of the Atlantic, buying regional distributors in North America and Europe, to establish a panregional presence.) Even with this consolidation, the super-regionals are trying to integrate acquisitions in a way that retains regional expertise and customer relationships.

In Asia-Pacific, the Japanese market also has some unique aspects. There is a strong role for trading houses—large corporations that not only distribute chemicals but also occasionally invest jointly with manufacturers in shared assets and handle arbitrage deals. Trading houses exist in other markets (such as China), but those tend to focus more on commodity chemicals. By contrast, trading houses in Japan—especially Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Itochu—are more focused on specialty chemicals.

The Customer’s Perspective: Expertise and Service Win

Chemical customers have very clear criteria for determining which specialty chemical distributor to partner with. The basics are still relevant: excellent logistics services (speed and precision) along with competitive prices. Yet there are also more segment-specific criteria, such as laboratory- and application-specific support, the capability and market know-how of the distributor’s sales team, the breadth of the products handled by the distributor, and the availability of key flagship products within the portfolio. Slightly less relevant are the ability to supply all of a customer’s production sites at once and flexibility in such things as order size and delivery frequency.

Larger distributors may be better equipped to deliver some of these aspects, but the central determinant is deep expertise in terms of segment-specific products, applications, and customers for a given geographic market. Simply put, expertise and service win among customers, not only at the level of product segments but also in individual subsegments. (See the sidebar “A Complex Recipe for Food Manufacturers.”) As a result, many specialty distributors are no longer scaling up for the sake of size alone; rather, they are now making highly targeted acquisitions to fill in portfolio gaps and key capabilities—and thus improve their profitability.

A Complex Recipe for Food Manufacturers

A Complex Recipe for Food Manufacturers

Often competition among specialty distributors occurs not only at the segment level but among subsegments. The food industry is a good example. It includes specialty chemicals for various subsegments (such as baked goods, sweets, dairy products, animal feed, and beverages), each of which requires a wide range of ingredients (such as preservatives, colorants, emulsifiers, texturants, enzymes, sweeteners, flavors, and nutraceutical ingredients). Each of these subsegments and ingredients has its own underlying market trends, which can also vary by region.

For food manufacturers—including beverage companies, bakeries, dairies, and the customers who buy the specialty chemicals—the result is a complex and dynamic landscape requiring superlative service for each ingredient category, in sync with overarching market trends. That raises the bar for specialty distributors in the food industry, but it also creates an opportunity for those that can excel in their execution, offering real market insights, superior service, and measurable value through the distributor relationship.

For example, some distributors with deep expertise in the value chain for food manufacturers are developing their own compounds and formulations, for example by combining different types of food ingredients into new solutions for their manufacturer customers. Similarly, some developed markets are seeing a shift toward smaller brands. These companies tend to place chemical orders that are smaller than those placed by large consumer-packaged-goods companies, and they can have a lower level of sophistication regarding formulations; both trends play to the strengths of third-party distributors.

Other M&A objectives include supporting a regional expansion and improving the logistics network, but the underlying rationale is the same: to create a comprehensive offering that is demonstrably better than any competitor’s in a key segment and region.

The Manufacturer’s Perspective: The Importance of Coherent Channel Management

In the past, the value of distributors from the manufacturer’s point of view lay primarily in servicing long-tail customers—those with small orders or those needing specific package sizes or ancillary services that the manufacturer couldn’t offer economically. Distributors were an extension of the manufacturer’s own supply chain; they weren’t directly integrated with that supply chain.

Over the past five years, that has changed. Producers now consider distributors to constitute a critical part of their overall go-to-market strategy. In an increasingly competitive market, the specialty distributor channel is a key means of reaching and developing small customers along with those in new markets. In some cases, manufacturers not only sell through distributors but actually buy some products back from them. (See the sidebar “When Sellers Buy.”)

When Sellers Buy

When Sellers Buy

Distributors can offer value to chemical manufacturers by helping them to source long-tail products that the manufacturer needs to buy only infrequently, in small quantities, or both. This essentially entails reversing the supply chain: rather than products flowing from manufacturer to the distributor and then to end users, products will flow from a manufacturer to a distributor and then to another manufacturer. This highlights the fact that the biggest customers for chemical companies are often other chemical companies. Just as distributors can help simplify the procurement process for customers—by providing one-stop shopping for a wide variety of products—they can simplify procurement for manufacturers as well.

As a result, many manufacturers have professionalized their relationships with distributors in several areas:

- Manufacturers define objective criteria and KPIs for when they will rely on third-party distributors, such as in markets below a preset revenue threshold.

- Manufacturers carefully screen distributors and choose them on the basis of such considerations as the distributor’s market or customer reach in a specific segment or geographic market, the size and breadth of its portfolio, or its portfolio of accompanying services.

- Manufacturers actively monitor the performance of distributors and provide both positive and negative incentives as needed. For example, most manufacturers do not initially establish long-term contracts; they prefer to wait until the distributor has proven itself. At that point, contracts of one to three years are standard, with clearly defined performance targets and other metrics.

- Manufacturers sometimes grant exclusive access to a specialty distributor for specific products in each geographic market. (This is in direct contrast to commodity-type segments, where manufacturers typically maintain relationships with multiple distributors to retain negotiating clout.) Exclusive arrangements have the added advantage of allowing manufacturers and distributors to share more detailed—and mutually beneficial—market information. Notably, exclusivity across an entire region, such as North America or Western Europe, is still rather uncommon; it would clearly simplify matters for manufacturers, but a panregional distributor with uniformly strong market coverage is hard to find.

Given this baseline, many manufacturers now have ambitions to establish a distribution management function. This function—typically set up as a corporate or regional center of excellence—can oversee relationships with specialty distributors across business units and bundle critical expertise for the manufacturer in such areas as contract management, performance assessments, compliance with environmental and sustainability factors, and other aspects. For example, the center could develop a coherent contract structure for all distributors in the portfolio, identify and share best practices among the different business units of a chemical manufacturer, and apply similar KPIs to ensure that distributors are being assessed consistently.

The Digital Value Chain

For chemical distributors, as for companies in all industries, digital technology poses both challenges and opportunities. Yet neither will likely disrupt the industry overnight. In the short term, there is little threat of disruption from a radically new business model or market entrant. Unlike products in media and some other industries, specialty chemicals are physical items that cannot be converted to ones and zeros. Moreover, the distribution of those products involves complex handling requirements, technical expertise, and services such as postsale support, safety and regulatory requirements, and documentation. These can’t be designed away with a clever app.

Some manufacturers have launched initiatives to use digital as a means to bring back to direct sales some smaller, long-tail customers rather than have them go through a distributor. These measures are still in the early stages, many involving a significant amount of trial and error, and they usually include websites and portals. However, we are skeptical that these measures will lead to a wave of customers leaving their distributor relationships to source chemicals directly from manufacturers instead. Distributors offer more than just reduced complexity; they bundle segment-specific products from a wide variety of manufacturers, offering something close to one-stop shopping for a given segment. This customer experience can’t be replicated by a digital offering from an individual manufacturer—only by a platform from a distributor that has relationships with multiple manufacturers. In addition, distributors offer logistics services, such as bundling many small-scale orders, that many manufacturers simply can’t match.

Over the long term, however, digital holds clear potential to transform specialty distribution by addressing some of the common pain points in the chemicals purchasing journey for customers (for example, digital product availability or online order tracking). As a result, distributors need to begin laying the digital foundation today. We believe there are clear opportunities for distributors in both the back end and the front end of their operations.

Regarding back-end applications, distributors can take the following measures:

- Optimize fleet or network operations to increase the efficiency and utilization of warehousing and transportation assets (either owned or contracted).

- Monitor such metrics as net working capital, sales levels, pricing, and other KPIs in real time to improve decision making.

- Digitize warehouses to make fulfillment processes more efficient.

- Assess orders across customers to make more accurate demand forecasts.

- Boost the targeting and accuracy of marketing and sales programs by gathering and incorporating richer information on customers and their buying behaviors.

- Most important, create transparency through data so that distributors can gauge their financial performance at the level of individual customers, products, and transactions.

These are not wildly innovative measures; rather, they are fairly standard ways to improve existing operations—a way for distributors to get better at what they are already doing—and they have already proven their merit in other industries. For distributors, however, they can lead to sizable gains in efficiency, customer service, and productivity.

In contrast, front-end digitization allows distributors to do new things through innovative business models that offer new types of services and customer journeys. To that end, distributors can improve sales channels through online portals that capitalize on a distributor’s offering across multiple manufacturers (for example, a marketplace that sells only washing detergents or one focused on bakery specialty chemicals). They can also increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the sales force through, for example, mobile applications for field reps, digital support for phone sales, and knowledge management tools for technical sales and on-the-ground application engineers.

How Distributors Can Win Through Digital

In the long term, digitization poses a real threat. Currently, distributors create value in a classic middleman role. They have information about manufacturers and end users, and they capitalize on that information to reduce complexity and create value for both groups. In other industries, however, digitization has made information far more transparent, upending this kind of information imbalance and eliminating the intermediaries. (Consider travel agents, for example.)

At a minimum, increased transparency through digital could lead to increased competition among distributors and reduced pricing power. It could also invite direct attacks on the distributor model from either startups or established digital players (such as Amazon) that create platform-based business models powered by digital, along with logistics providers that extend into marketing and sales.

Yet distributors have several advantages in fending off the threat of disintermediation by manufacturers and disruption by digital attackers. Specifically, distributors have built vast portfolios in which they bundle products by segment. If you are a food manufacturer or a water-treatment facility or a coatings company, you can source all specialty products through a small number of relationships with distributors (and sometimes with just one distributor). Where distributors can improve on this offering is through digitized information, seamless online transactions, and deep customer experience. They must compile comprehensive, detailed data on the product attributes, formulations, applications, and other information for the tens of thousands of products in their portfolios, and make that information available to customers as a means of boosting distributors’ value proposition. In this way, they can make themselves a one-stop shop for product information, as well as for the products themselves.

Winning solutions are relatively easy to visualize. They will be online marketplaces that are tailored to specific industry segments, with reassuringly comprehensive offerings that meet any conceivable chemical need for a company operating in that segment. They will offer highly detailed, digital product information—all product attributes, formulations, handling requirements, and any other data—for every product in the portfolio and in a customer-accessible format. They will have a clear and intuitive online interface, designed to meet the needs of specific types of customers. (For example, a distributor could set up one entry point to its online site for repeat purchases from recurring customers and another for customers seeking to navigate the selection of new products or offerings for new applications.) And they will complement this digital storefront with excellent application advice, formulation services, and strong logistics via an efficient, digitized supply chain that offers customers visibility into order status. The result will be an end-to-end digital supply chain, from the development of new products and formulations among manufacturers all the way through to the physical delivery to customers.

Distributors are in the best position to capture this opportunity—by combining new digital services with their current strengths in the physical value chain. However, if they wait, the opportunity will be claimed by existing digital players, such as Amazon, that already know how to combine digital and physical solutions.

This may seem like a big step for many distributors. It is in some ways but not in others. Most already have a bundling business model in place, through which they source products from a wide variety of manufacturers and sell a comprehensive portfolio of products. In addition, most have built up detailed product information—it’s just not in digital form yet. Building on these advantages will take work and require changes in the business model. Distributors need to begin digitizing product information and supply chain operations through early proof-of-concept pilots and other initiatives to generate momentum, and then build up digital expertise and scale up winning ideas. The required changes in mindset and core beliefs will be at least as substantial as the content changes.

The Way Forward

Our experience indicates that there are five imperatives for specialty chemical distributors.

Get the basics right. Focus on the key decision criteria of customers. Most want speed and precision in logistics, along with competitive prices. In addition, tailor service offerings to the specific needs of customers. These services include technical support, packaging, storage, and other logistics services, along with precise, transparent data on individual transactions, such as profitability, cross-selling opportunities, and segment coverage.

Focus on specific segments and subsegments. Sheer size alone is not relevant; rather, distributors should seek to excel in a particular segment and subsegment—and for a given geographic market—through comprehensive product offerings and strong customer relationships. They can offer application support to customers and also work with manufacturers in the development of new products and formulations.

Balance panregional coverage (for manufacturers) with a regional focus (for customers). Manufacturers prefer panregional distributors because they offer the widest possible coverage with the smallest number of distributor relationships. But customers are typically small and geographically contained. Distributors need to balance those two opposing forces.

Professionalize interactions with manufacturers. As manufacturers focus on professionalizing their distributor management function, distributors must respond in kind. For example, they should be able to quantifiably establish the value they create for manufacturers through sales growth, new customers, and new markets. They should also be able to apply standard KPIs to demonstrate performance against contractual criteria and share marketing trends, customer insights, and other information with manufacturers.

Begin building a digital supply chain, starting with segment-specific marketplace offerings. Finally, distributors must begin investing in digital tools. For back-end operations, this includes automating warehouses, using artificial intelligence to better predict demand, and applying analytics to understand profitability at the level of individual transactions and products. For front-end operations, distributors can use the current bundling business model to create segment-specific online marketplaces that combine digital product information with best-in-class logistics services.

Specialty chemical distribution continues to be an attractive market, with growth rates that exceed that of global GDP and overall chemical consumption. Yet distributors cannot sit back. Consolidation, stronger distributor management among manufacturers, and potential disruptions from digital are all creating a more dynamic market. Forward-looking management teams will get ahead of these shifts by assessing their impact and taking the necessary steps to position themselves to capitalize. Those that don’t will risk being overtaken by the competition—potentially permanently.