Offshore wind could move from niche status to being a leading source of renewable energy worldwide. Industry players are betting that policymakers will act to promote the accelerated, long-term growth of offshore-wind power in Europe, where it is most advanced. This support would drive the development of a global market that could be worth a cumulative €700 billion by 2030—exceeding most market estimates. But this is not a given. Whether we see accelerated or business-as-usual growth depends on better auctions, investment in electricity grids, supportive public policies, and power market changes. Wind farm developers, installers, and suppliers need to future-proof their business models by making smart decisions about the evolving landscape and gaining a better understanding of the risks and opportunities associated with a variety of scenarios.

The Market Potential of Offshore-Wind Power

European offshore-wind-power developers are beginning to submit zero-subsidy bids at auctions in the expectation that a bigger market will professionalize the industry, allow for manufacturing at scale, and deliver technology-driven cost reductions. All these factors are needed to improve margins and position companies to make handsome profits.

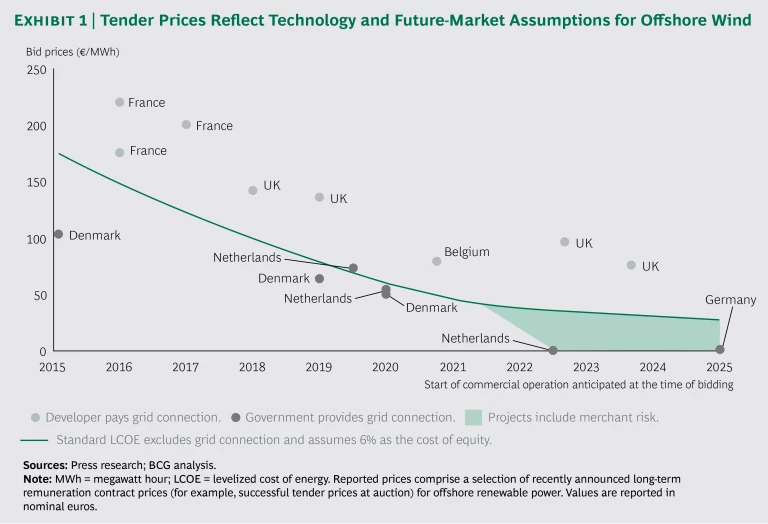

In April 2017, German utility Energie Baden-Württemberg (EnBW) and Denmark’s Ørsted (formerly DONG Energy) won three out of four projects in Germany’s first-ever auction with zero-subsidy bids. Recent auctions have confirmed the downward trend in prices. (See Exhibit 1.)

Factored into these bids are the expectations that generating costs will decline from more than €100 to less than €50 per megawatt hour (MWh) by 2025 and that the wholesale price will recover from current levels. This, in our view, is a realistic scenario.

Until now, offshore wind has played second fiddle to other renewable sources. Even in Europe, it accounts for only some 8% of renewables’ generating capacity. One reason for this is that risks and project costs are higher, and operation and maintenance activities are more complex.

At the same time, generous subsidies and limited capacity have benefited a variety of players and business models. Although European governments, starting with France in 2012, switched to auctions for contract awards, politically motivated requirements, such as local content and location, meant that bidders could count on state support. Consequently, the industry lacks scale, and key elements of offshore-wind power are less mature than those of solar or onshore wind.

But that’s changing. Governments are picking up a share of project costs, developing sites, and building interconnectors to the grid. These changes have forced developers to focus on building and operating wind farms. The universe of players is also evolving. Four large energy companies—Ørsted, Vattenfall, E.ON, and RWE—operate more than 40% of Europe’s capacity. However, Royal Dutch Shell and Statoil have recently strengthened their commitment to the market.

How Europe Will Dictate Global Growth

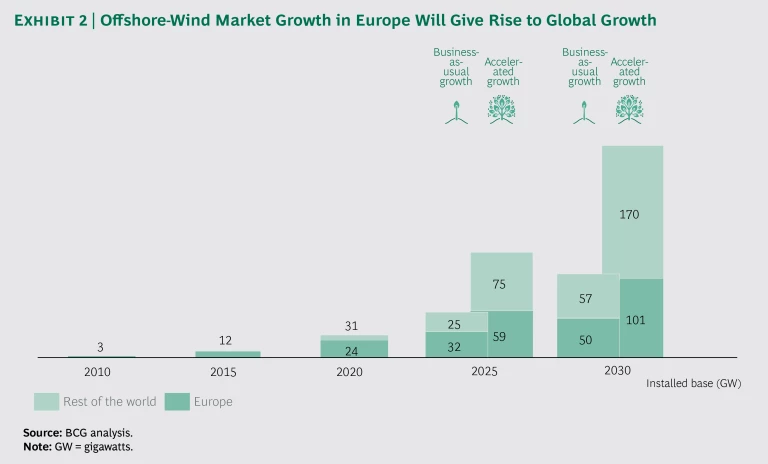

Europe is key to the industry’s success globally. The rate of growth in Europe will determine the level of competition, the pace of technological development and supply chain maturity, and the industry’s future shape. European companies could become market leaders worldwide. We expect that under an accelerated-growth scenario, the share of capacity outside Europe will rise to more than 60% of the global total by 2030. (See Exhibit 2.)

Europe’s offshore-wind capacity, which currently stands at about 12.5 gigawatts (GW), accounts for 90% of the global total. But it supplies just 5% of Europe’s electricity. According to WindEurope, an industry association, generating capacity from Northern Europe’s sea basins could reach 10 to 20 times the current level by 2030, offshore wind producing electricity at €55 or less per MWh. This, however, will depend on the dramatic upgrade and expansion of transmission systems. Realizing offshore wind’s potential in Europe rests on the following:

- To invest, the industry requires a viable project pipeline, so governments will have to raise capacity targets, expand infrastructure, and tackle transmission bottlenecks. Developers need to be locked into building farms. They’ll have to shorten the time between bidding and construction, exclude companies that don’t complete projects, and raise bid bonds.

- Power markets need to account for the intermittency of renewables, increasing intraday trading. We estimate that market efficiency measures could eliminate about €4.8 billion in costs per year, or €1.5 per MWh, from the system.

- Governments will need to stop using offshore wind to further political aims by, for example, supporting domestic companies and regions.

Europe’s power markets are progressing. Several exchanges are enhancing cross-border intraday markets, cutting the time between trading and delivery to considerably less than one hour. New regulations will allow wind power producers to shut down when electricity networks have surplus power. Conversely, once these regulations are in place, wind farms will be able to meet demand surges using new battery technologies. We expect that B2B trading will provide operators with more predictable cash flow. In the US, B2B purchases comprise more than 50% of renewable energy sales.

However, in an era of political uncertainty, it remains to be seen whether governments will invest in the grid infrastructure that is needed to support offshore wind or will provide capacity payments to keep “peaker” plants (which are used only during periods of peak demand) online as backup for intermittent renewable sources. Depending on how these forces play out, two alternative growth scenarios could develop.

The Accelerated-Growth Scenario. If governments invest significantly in grid infrastructure and expand their tender pipelines, European capacity could rise by a CAGR of 16%—or 7 to 8 GW per year—and reach about 100 GW by 2030. Offshore wind would become a significant renewable energy source, enhance the role of renewables in balancing electricity networks, and enable Europe’s governments to honor the commitments they made at the 2015 Paris climate change summit.

Installing 7 to 8 GW of new European capacity annually would support the following developments:

- Two European OEMs together producing 600 to 700 turbines a year

- Two to three installers, with vessels that function in harsher weather than today, reducing installation and commission times from the current five days to one to two days

- Three to five manufacturers building foundations, with considerable offshoring to the Far East

- Interconnection costs, which currently add between €12 and €20 per MWh to offshore wind’s levelized cost of energy, dropping by as much as 66% as a result of deregulation, price competition, and greater use of high-voltage, direct current (HVDC) transmission lines

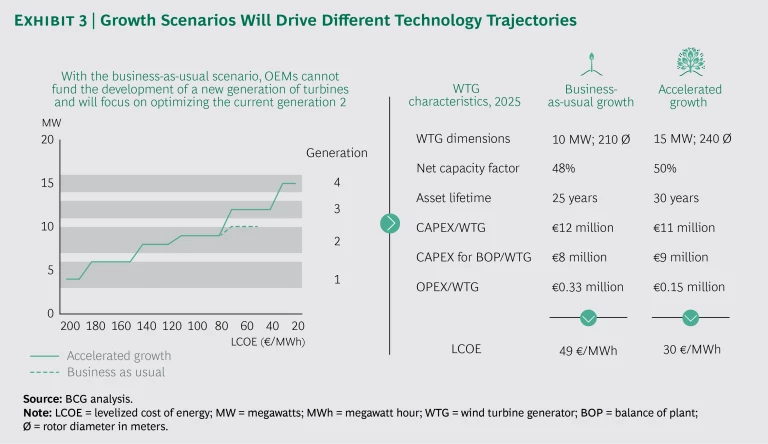

Such capacity growth would foster specialization, competition, and disruptive and innovative technologies. (See Exhibit 3.) Still, it would leave the industry vulnerable to fluctuations in volumes. However, incumbents could expect margins ranging from 9% to 11%.

Progress in Europe would stimulate markets elsewhere to grow by a CAGR of 42% until 2030, and global capacity—excluding Europe—would reach 170 GW. Offshore capacity would be low compared with onshore and solar, but it would be a meaningful contributor to global energy needs.

Helped by improvements in battery technology, offshore would be almost a base-load power source that is available most of the time, reducing the need for governments to balance the consumption of grid electrical power with supply. Installation and maintenance would be sources of significant job creation in coastal regions, removing the need for local-content requirements at auction. Owing to the buoyant market, developers could end up paying governments a license fee for the right to operate, just as oil companies pay for extraction rights.

The Business-as-Usual Growth Scenario. Extrapolating from current policies, we see capacity in Europe growing by a CAGR of 11%—or about 2 to 3 GW per year—to 2030 and reaching about 50 GW before leveling off at 60 to 70 GW by 2040 and then slowly declining. Offshore wind would remain a niche sector. The market would support a stable installed base of wind farms, with new turbines replacing older ones, provided that low-cost solutions were available.

Many current players would likely divest their European operations to concentrate on opportunities outside the region, while the prices in future auctions would rebound and projects would again be dependent on significant subsidies. Recently won projects would probably be scrapped, and companies’ bid bond guarantees would be written off because they would not achieve promised cost reductions. Today, Europe’s policymakers might be praising themselves for achieving double-digit growth, but if this pace continues, the reality will be a high degree of consolidation and unsustainable profit margins. The annual addition of 2 to 3 GW of new European capacity would delay—or even end—development of giant 15-MW next-generation turbines. Consequently, we would expect the following:

- Production volumes of around 400 turbines a year would not be enough to support two OEMs innovating and manufacturing at scale.

- Installers would hold off on making significant investments and upgrading their fleets. As a result, there would likely be more—four to six—installation companies competing fiercely on price and using multipurpose equipment.

- Most manufacturers would be happy to secure orders for 50 foundations a year.

- The adoption of HVDC transmission lines would be slow and extremely costly. The expense of connecting to the grid would remain high owing to market regulation, widespread overcharging, and significant sunk costs.

Limited professionalization would mean that the offshore industry did not benefit from falling costs, and few players would achieve satisfactory profit margins. Under this scenario, it would also be impossible for European governments to honor their climate change pledges from the Paris summit.

Weak European growth would likely restrain growth in other markets as well. Outside Europe, capacity would increase by a CAGR of 32%, reaching some 57 GW by 2030. Players in Europe would shift their regional focus. As a result, we would see parallels to what happened in the European solar power industry over the past decade, with new investment taking place outside the region.

What Got Us Here Won’t Get Us There

When it comes to planning for the future, what got us here won’t get us there. No matter which scenario becomes reality, a different competitive landscape is likely to emerge from today’s.

In a world without subsidies, operators would have to take on so-called merchant risk—exposure to the fluctuating price of wholesale electricity. Owing to the risk-averse investment mandates of pension funds and insurance companies, this would theoretically prevent them from participating in offshore projects. However, institutional investors are likely to find ways around this. We expect to see new risk mitigation products that will help companies manage fluctuations in price and volume. These will be similar to the insurance and reinsurance products that we see today in other sectors, but they will probably be offered by new providers.

To develop their business plans, executives must anticipate the industry’s direction. They need to review their assumptions for future growth and select a scenario for making plans and investments. Because of the industry’s changeable outlook, executives can’t rely on strategies that worked in the past. But by failing to map out a vision that drives the company’s activities, they risk falling behind rivals. (See the sidebar.)

Early Indicators of Accelerated Growth

Early Indicators of Accelerated Growth

Executives who want to adapt their strategies to movement in the market must be alert to early signals. In the event of accelerated growth, we expect these signals will include the following:

- A widespread redesign of public feed-in schemes, including the removal of fixed state support schemes and the requirement that companies accept merchant risk

- Major initiatives to upgrade electricity grids that provide for the injection of offshore-wind energy

- Removal of electricity trade barriers

- International increases in the adoption of carbon taxes in support of the transition to renewables

- Large orders for cable-laying, dredging, and installation vessels as transport and installation suppliers become more specialized

- Banks and investors growing comfortable with merchant risk (exposure to the fluctuating wholesale electricity price), early indication of comfort levels being indicated by the financing of Spanish wind farm projects tendered

- The emergence of reinsurance products that allow utilities to mitigate merchant and other risk

- A review of trade restrictions that limit the development of a global offshore-wind market, such as the Jones Act, which governs US maritime trade, and Taiwan’s ban on energy products imported from China

- Rising global prices for conventional energy that make renewables such as offshore wind more attractive

- GDP growth above 3% and a shift to electric heating and e-mobility, which support a growing need for renewable energy

If in Doubt, Aim High

In today’s evolving energy landscape, companies cannot completely avoid making the wrong assumptions and ending up with stranded assets. We cannot say with certainty which of our two scenarios will become reality, but a middle-path scenario is unlikely. Successful technologies tend to benefit from an S-curve effect of strong and rapid market penetration, while weak technologies wither. Projections can also turn out wrong owing to the failure to commit to a scenario and being forced to compromise. We see strong business and social arguments for the accelerated-growth scenario in offshore wind. Therefore, we believe that, if they are in doubt, executives should aim high.

Shaping the organization to be competitive under an accelerated-growth scenario carries the lowest risk. Companies should prepare for change, create value, and reinforce their position in the value chain. Under this scenario, pure players—standalone companies or self-contained business divisions of larger groups—stand to benefit the most because of their focus on specific business areas. They have other advantages as well: they are nimbler at adapting in evolving markets such as offshore wind, and they are better able to control internal costs than large, diverse groups.

Optimizing for an accelerated-growth scenario will require companies to consider taking several steps.

Determine the company’s sweet spot in the value chain. Until now, offshore-wind operators have carried out activities along the value chain because it was the most effective way for them to manage a project’s lifetime risks. Ørsted, the European market leader, took projects from early-stage development through decommissioning, for example. By investing in engineering capabilities, Ørsted dominated in engineering, procurement, construction, and installation. However, the company has increased its focus on offshore development by divesting all noncore businesses, such as its onshore and traditional oil and gas divisions, and by exiting the installation business. We expect to see less vertical integration and more consolidation within specific steps along the value chain. Financing and owning wind farms will become more important standalone elements of the value chain. Companies that are already specialized and do not have the legacy of multiple divisional layers will have an advantage.

Operate as a pure player. Companies need to operate their offshore business as if they were pure players, not compromising this approach by searching for synergies in other parts of the corporation. Large organizations need to deconstruct their business activities, optimizing each one on its own merits. Companies today still tend to bundle their offshore activities, risking a loss of focus and value creation. For example, E.ON’s Climate & Renewables division bundles activities around technologies, while EnBW, by putting all its offshore, onshore, and thermal operations in one unit, bundles along the value chain. Ørsted is one company with a relentless focus on offshore wind. By divesting assets and changing its name, it has stepped away from onshore wind and removed all references to its history of oil and gas production.

Create effective interfaces. The interface among companies and among divisions of a single group will gain importance as wind farm operators and suppliers specialize and relinquish certain roles. For example, operators will need access to advanced data analytics solutions from software suppliers that rely on data sharing in order to analyze and optimize the performance of their wind farms. To do this, operators will have to forge agreements with OEMs and data analytics providers. These accords should give operators greater insight into the ways that their valuable data is being used and guarantee the data’s protection from rivals.

When optimizing the organization for accelerated growth, management must make some difficult choices about such concerns as whether and when to invest in new foundation and cabling technologies and installation capabilities. The Swiss Army Knife approach may seem the safest, but if a company is planning for accelerated growth, it can’t afford a generalist approach: every additional tool on the knife adds costs and reduces operational efficiency.

Offshore wind could become a major source of global renewable energy. Faced with an uncertain future, offshore companies that build their strategies on the expectation of accelerated growth—and resist the temptation to be generalists—are likely to outperform rivals. The companies that flounder will be those that fail to adjust to the new reality, assuming that what’s worked in the past will work in the future.