To get the most value from digital acquisitions, dealmakers need to think more creatively about synergies. Less tangible sources of value—such as scientific acumen and social media influence—are critical to justifying the high price of digital assets. Acquirers must be able to tap into these sources of value to grow their own business, as well as apply their core strengths to accelerate the digital asset’s growth.

That’s not to say that traditional synergies are unimportant. Dealmakers must still identify the traditional opportunities to improve costs and revenues (such as headcount reduction and cross-selling) that an acquisition could create. They must also solve the puzzle of how to preserve the value-creating attributes of a newly acquired digital asset as they integrate it into the parent organization.

Successful acquirers have demonstrated that all these imperatives can be met. Taking the right steps to identify, quantify, and extract the less tangible sources of value is the key to cracking the code of digital.

Digital Dealmaking Accelerates

Companies increasingly recognize that they must proactively respond to digital disruption in their industries. The natural inclination for many is to try to develop digital capabilities in-house. However, the rapid rate of digital innovation has meant that new capabilities quickly go out of date, sometimes even before they are fully implemented. Additionally, traditional companies have struggled to attract digitally minded millennials to their workforce. The interrelated imperatives to accelerate adoption and compete in the talent war are compelling companies to buy, rather than build, digital capabilities.

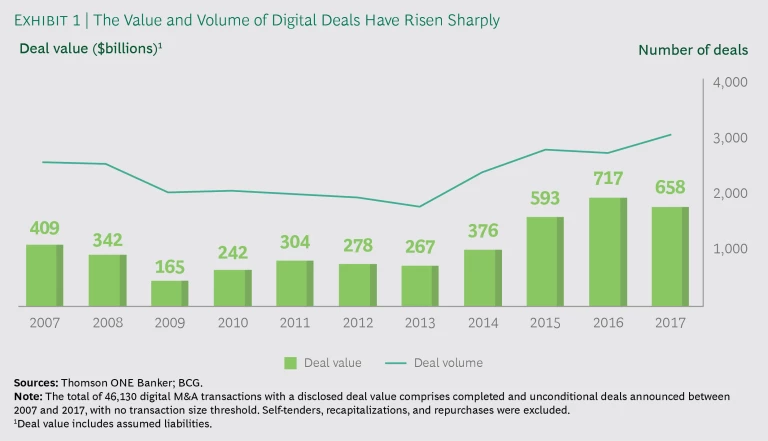

Indeed, corporations’ appetite for digital acquisitions has accelerated rapidly. In 2017, the global value of digital M&A deals reached $658 billion—more than double the value five years earlier. (See Exhibit 1.)

Digital deals represented 24% of the entire M&A market. Companies from outside the tech sector seeking to acquire digital capabilities now account for two-thirds of all digital deals. (See the sidebar, “Identifying Digital Deals.”)

IDENTIFYING DIGITAL DEALS

IDENTIFYING DIGITAL DEALS

Identifying digital deals demands careful analysis and expert knowledge. BCG developed its own classification taxonomy for digital transactions based on nine digital and high-tech trends. Our goal was to develop a working definition of digital and technology targets that goes beyond the broad categories of the Standard Industrial Classification system to include companies that have some form of digital product or technology as an essential attribute or part of their business model.

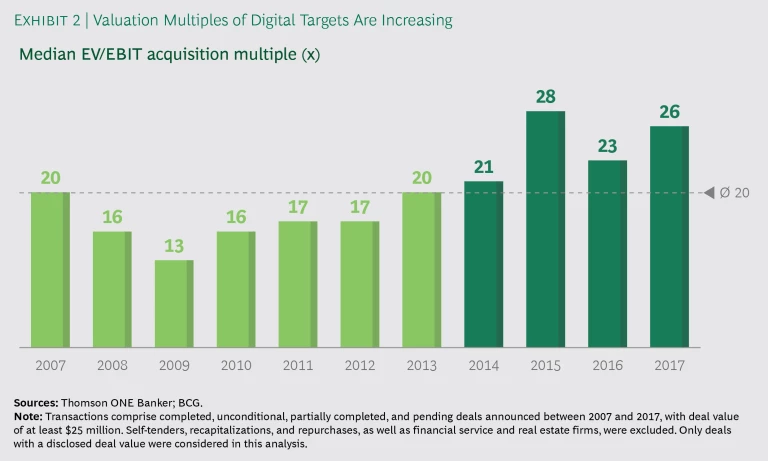

The average value of digital deals involving corporate acquirers was $151 million in 2017. Deal activity focused on relatively nascent companies: 81% of digital deals were valued at less than $100 million, while only 3% exceeded $1 billion. Digital companies sold at near record multiples—the median EV/EBIT multiple was 26x. (See Exhibit 2.)

Soaring valuations make it harder than ever for dealmakers to prove to boards and shareholders that digital acquisitions are worth the high price. Dealmakers have traditionally relied on cost synergies to demonstrate a deal’s value. However, most digital acquisitions offer limited opportunity to extract significant cost synergies, and seeking to reduce costs by integrating operations is risky.

As a result, companies increasingly need to justify digital acquisition multiples through nontraditional synergies, including those arising from the use of digital marketing capabilities, direct-to-consumer supply chains, automation, and artificial intelligence. Because the benefits are typically intangible, they are hard to quantify. Adding to the challenges, as the level of synergies announced in digital deals increases, investors are becoming more skeptical that companies will be able to deliver on their promises. A similar trend is observed in the overall M&A market. (See The 2018 M&A Report: Synergies Take Center Stage , BCG report, September 2018.)

Maximizing Value from Search Through Integration

To succeed with digital acquisitions, companies must follow the traditional multistep approach, but expand the toolkit to adjust for the nontraditional characteristics of these deals.

Step 1: Search for Targets in Nontraditional Ways

Before entering the M&A market, the company should determine which capabilities it needs in order to respond effectively to digital disruption. It must gain a thorough understanding of the technology trends affecting its business and where its competitive advantages lie today and could lie in the future.

This assessment provides the basis for establishing clear parameters for the digital assets that the company wants to pursue. Such parameters include business or value chain segments, services, products, geographic regions, and adjacent sectors.

In searching for digital targets, the company should evaluate both traditional data that is directly attributable to financial performance and nontraditional data that can be indicators of the company’s future performance. Such nontraditional data includes the rate at which a target is acquiring new customers or social media sentiment relating to the target. To identify digital businesses that have real substance, companies are increasingly analyzing data on academic grants, publications, intellectual property, scientific collaboration, and industry connections. They are using the insights gained to create a broad set of criteria for identifying and prioritizing potential targets.

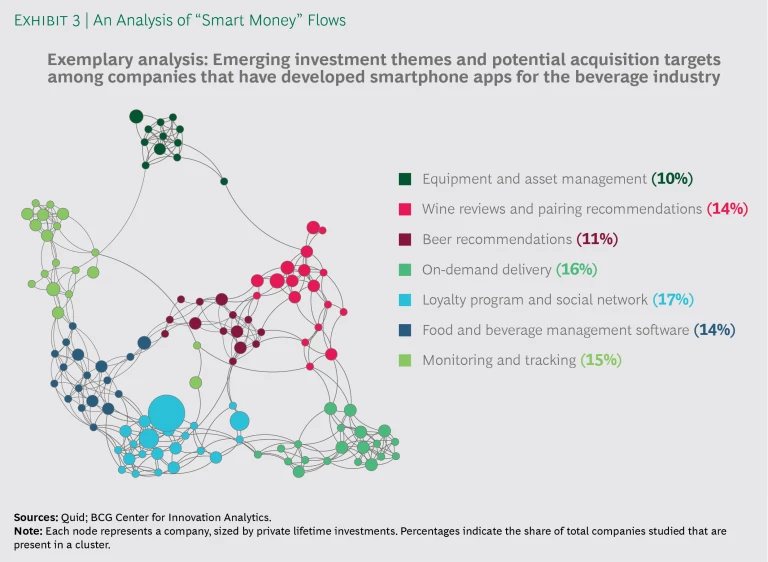

To facilitate their target scans, leading companies use cutting-edge data science, data visualization, proprietary tools and algorithms, and third-party tools such as Quid. These techniques allow them to mine data and apply text analytics across multiple sources. Exemplary applications, supported by BCG’s Center for Innovation Analytics, include the following:

- Analysis of “Smart Money” Flows. By applying natural language processing to data from Capital IQ and Crunchbase, Quid creates a thematic map of companies based on their common products, technologies, and services. This mapping gives the company a segmented view of where venture capital is flowing within a given investment range. The analysis has been used to identify emerging investment themes and to highlight potential acquisition targets with great specificity. For example, such a scan can identify companies that have developed smartphone apps for the beverage industry. (See Exhibit 3.)

- Network Analysis. By mapping nontraditional networks, such as those relating to patent citation and scientific collaboration, companies gain insights into a technology’s application to, and ability to gain traction in, new markets. This analysis also highlights which players are most influential and collaborative and are emerging most strongly. A company’s propensity to collaborate with other companies and connect to isolated parts of a network can be indicators of a breakthrough innovation and higher likelihood of success.

To succeed with digital acquisitions, companies must expand the toolkit to adjust for the nontraditional characteristics of these deals.

- Sentiment Analysis. A scan of social media and web activity can be used to quantify sentiment, both positive and negative, toward a given company. The results can help to highlight companies that are actually gaining traction in their markets and have high shares of unpaid media exposure.

Corporate acquirers can use artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to prioritize companies, innovations, and initiatives with the greatest likelihood of success. For example, a model developed by BCG applies artificial intelligence and nontraditional metrics to help predict the success of early-stage companies. This approach was tested with 267 immuno-oncology companies, applying eight categories of data that encompass more than 70 nontraditional metrics (such as scientific acumen, patent strength, and founder experience). If this model had been used in 2014 to predict the success of early-stage immuno-oncology companies, it would have identified several little-known companies that would become major successes by 2017. When ranking companies’ likelihood of success on the basis of 2014 data, the model correctly predicted, in more than 70% of cases, whether companies would outperform or underperform relative to their peers in 2017.

Step 2: Evaluate Targets’ Value with a Digital Mindset

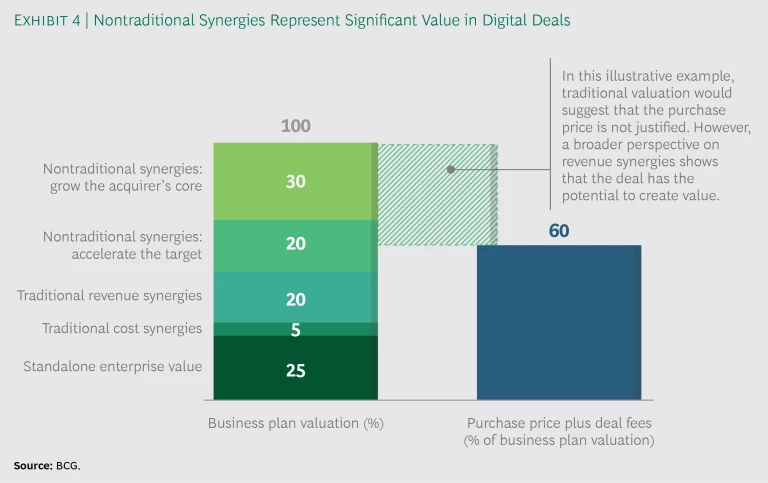

To evaluate the economics of an acquisition, dealmakers have traditionally determined the target’s enterprise value and developed a business plan that estimates the cost and revenue synergies generated by integrating the target into the acquirer. If enterprise value and synergies exceed the acquisition price, then the deal has a positive business case. However, this traditional approach fails to capture two categories of revenue synergies that are critical to justifying the high multiples of digital acquisitions:

- Accelerating the Target. Acquirers can accelerate a digital target’s growth by providing access to its capabilities, capital, and global reach. Creating a business plan for the target that applies the acquirer’s strengths—such as access to markets, customers, or partnerships—can add substantial value.

- Growing the Acquirer’s Core. Acquirers can leverage the target’s capabilities to create new business models and service lines that generate significant value, which could thereby grow the company’s core business.

By including such synergies in the business plan, dealmakers may find that the purchase price is justified. (See Exhibit 4.)

To assess nontraditional synergies, dealmakers should consider three sources of value:

- Capabilities and Specialist Knowledge. An acquirer can leverage the target’s capabilities and specialist knowledge to accelerate its own growth. Expertise in product development, digital marketing, analytics, and direct-to-consumer supply chains can be extremely valuable. A number of digital tools are available to highlight or quantify areas of strength. For example, by reviewing the qualifications that a target’s personnel list in their LinkedIn profiles (such as PhDs in computer science), dealmakers can gauge the actual depth of the expertise at the company.

To fully gauge the potential value of a proposed transaction, it is critical to evaluate the economic impact of alternative scenarios.

- Stakeholder Influence. The depth and breadth of a target’s stakeholder relationships and connections are good indicators of its future success, as well as of an acquirer’s ability to extract value, such as through cross-selling. An acquirer can measure the strength of the target’s user or customer base, for example, by analyzing the company’s social media following, online reviews of the target’s products, and online sentiment.

- First-Party Data. A digital target often collects data about customers and suppliers that can be analyzed to better understand their needs and behaviors. The insights can be used to improve the target’s offering, strengthen its relationships, and drive better decision making (such as capital allocation). The acquirer can also apply the data to grow its core business. In assessing the value of first-party data, companies must consider the need to comply with data privacy laws and requirements, such as the EU’s recently introduced GDPR.

To fully gauge the potential value of a proposed transaction, it is critical to evaluate the economic impact of alternative scenarios. For example, a competitor might acquire the target instead and capture the benefits. Moreover, building the relevant capabilities in-house would entail costs and could generate less value. A deal’s economics should also be compared with that of other potential acquisitions to demonstrate that it is the best option. By presenting a clear evaluation of the downsides of not acquiring a target, dealmakers can significantly affect how boards and shareholders view a proposed transaction.

Step 3: Differentiate Your Offer to Woo Digital Targets

To execute a digital deal, acquirers must be prepared for a fast-paced and highly competitive auction. Acquirers need to focus their review on the areas where both traditional and nontraditional value lie and seek to minimize potential liabilities. The team conducting the review will likely need specialized knowledge to probe nontraditional sources of value effectively.

An acquirer must differentiate itself from its competitors by ensuring that the terms of the proposed transaction clearly set out its vision for creating value. To develop a proposition that addresses stakeholders’ objectives in selling the company, the acquirer’s dealmakers should assess the motivations and priorities of investors on the target’s capitalization table and its management team. For example, venture capital investors may be looking for a specific exit multiple and return on investment. In contrast, the management team may be more interested in having a single owner provide capital, so that it can focus on running the business rather than fundraising.

It is essential for acquirers to articulate the growth opportunities and other benefits arising from the deal. This includes specifying how the combined businesses will achieve the goals of accelerating the target and growing the core. The postacquisition vision should generate excitement within the target’s management team. Moreover, the acquirer’s investors and management team will want to see that there is a path to capturing the promised benefits. The acquirer and target must also agree on the joint business case and how it will be achieved, including whether the target’s leaders and other key personnel will be retained.

Step 4: Manage the Integration to Preserve Value

After the deal is signed, the parent company must manage the integration of the digital business so as to preserve, not destroy, the value that justified the acquisition. The pace of integration must be carefully determined, balancing the need for speed against the risk of harming the newly acquired business by proceeding too fast. Aggressive efforts to impose the parent company’s processes and policies can decelerate growth and hasten the departure of key managers and staff members. At a high level, the following steps represent best practices for integrating and operating a newly acquired business:

After the deal is signed, the parent company must manage the integration so as to preserve, not destroy, the value that justified the acquisition.

- Preserve and experiment. To preserve the new business’s value, the parent should lock in key management and staff (such as analytics teams) with retention agreements. These key people often represent a high share of personnel. It should also maintain the business as a standalone entity, with arm’s-length management. To avoid overburdening the business with processes, it should introduce a simple governance structure. Additionally, the parent should seek to retain the culture and feel of the business, such as by not relocating personnel to new office space.

During this stage, the parent should experiment with options for accelerating the growth of the acquired business, such as by providing capabilities and funding. For example, parents typically invest to boost distribution or advertising or test the feasibility of manufacturing the acquired company’s products in-house. The growth plan should be developed jointly by both businesses as equal partners.

- Cooperate and grow. After the businesses have become familiar with each other’s personnel and processes, they must carefully manage the transfer of knowledge and capabilities. Pushing too hard or too fast, such as through large-scale transfers of staff from the parent to the digital business, can lead to attrition or a clash of cultures. The right approach entails arranging for temporary assignments of staff between the two businesses and conducting workshops to share best practices and identify opportunities.

- Integrate over time. In the next phase of the integration, the parent can transition in a new team to manage the acquired company. This transition also needs to be managed carefully, so as to prevent the loss of knowledge. After installing a new management team, the parent typically integrates the two businesses’ noncritical functions and operational areas (such as supply chain, procurement, and finance). Many businesses do not integrate highly specialized functions (such as analytics and innovation), because the risk of undermining these functions’ performance outweighs the benefits of integration.

Case Study: Unilever and Dollar Shave Club

In 2011, Dollar Shave Club (DSC) launched a subscription-based service offering three models of razors, each at a different price point, and automatic replenishment of blades. By 2018, DSC’s unit share of the men’s nondisposable razor market had climbed to 27%. Procter & Gamble’s Gillette, the leading incumbent brand, responded by reducing prices by 8% from 2015 through 2017 and launching its own subscription-based model.

Acquiring DSC's superior direct-to-customer capabilities meant that Unilever did not need to develop the expertise on its own.

DSC’s success attracted the attention of Unilever. In August 2016, the consumer products giant acquired DSC in an all-cash transaction for a reported $1 billion (equal to about five times revenue). The deal terms locked in DSC’s CEO, CFO, and COO. Unilever’s objective in buying DSC was to tap into its direct-to-consumer capabilities and proprietary analytics, not to enter the men’s grooming market. Unilever sought to learn how to acquire and retain online customers and how to manage digital marketing and logistics operations.

To achieve these objectives, Unilever has integrated DSC in phases. DSC operates as a standalone independent subsidiary (with separate financials) in the North America business unit. Its board is composed of its CEO (and founder) and three Unilever executives: the CFO, the president of the North America business unit, and the head of products. This simplified board structure gives the CEO greater autonomy over decision making compared with the pre-acquisition structure, which included venture capital investors.

Unilever has provided funding and expertise to support DSC in exploring and developing its direct-to-consumer model and platform. For example, DSC has expanded its razor subscription model internationally and launched new products, including an oral-care product line, in the US.

Benefits are also flowing to Unilever. DSC gives Unilever access to well-honed capabilities in direct-to-consumer sales and related skills in analytics and customer segmentation. Unilever rotates its employees through temporary assignments at DSC, so that they can learn about these capabilities and gain experience in applying them.

In 2017, Unilever launched two direct-to-consumer offerings: Skinsei (a skin care brand) in the US, and Verve (a subscription-based fabric care product) in the UK. The company is also using direct-to-consumer capabilities to reinvigorate its portfolio brands. For example, Nexxus, a premium hair care brand, has launched a subscription service. And dressings brand Hellmann’s has partnered with Quiqup, an on-demand delivery startup, to launch a service that delivers recipe ingredients directly to consumers.

Early results are promising. Unilever’s e-commerce revenue has increased by 45% since the acquisition. The company has announced that it expects experience platforms and e-commerce to reach 30% of revenues in 2022, from 15% in 2012.

As a former vice president of Unilever explained to us, acquiring DSC’s superior direct-to-customer capabilities meant that Unilever did not need to develop the expertise on its own, “slowly and painfully.” Ultimately, he expects Unilever’s brands to share a common direct-to-customer platform for analytics and fulfillment. The platform will enable the brands to benefit from DSC’s experience, without having to repeat its mistakes.

Companies must turn to M&A to survive the current cycle of digital disruption. They can apply the capabilities and know-how obtained in digital deals to establish a more agile operating model, foster the development of an innovation-focused culture, and attract digitally minded millennials to their workforce. However, digital targets are expensive, competition for them is fierce, and the nontraditional synergies required to justify these deals are difficult to quantify. To overcome the challenges, corporate leaders must develop a broader perspective on value creation and empower executive teams to pursue the synergies. Companies that crack the code of digital M&A will be well positioned to deliver superior shareholder returns in the years ahead.