This article is based on Decoding the Chinese Internet 2.0: Get Ready for the Next Chapter from Boston Consulting Group in conjunction with Chinese internet companies AliResearch and Baidu Development Research Center.

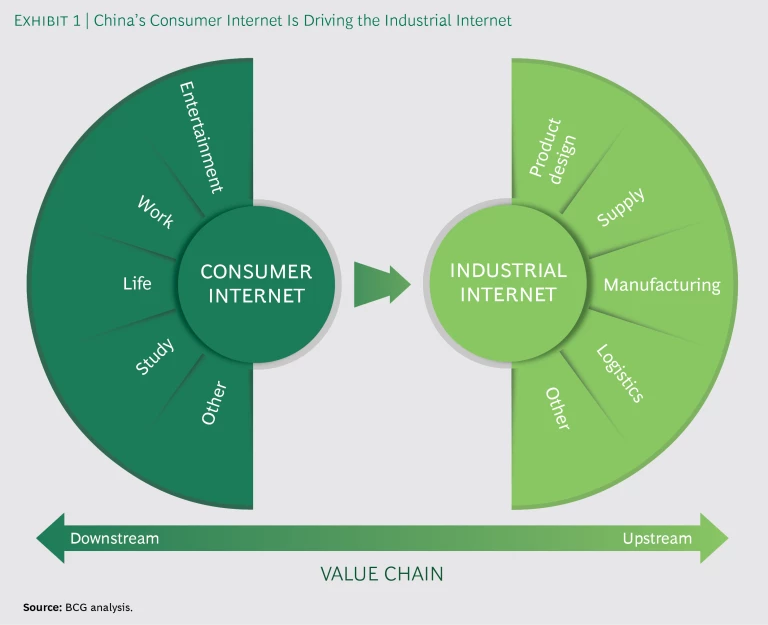

Now that China’s internet giants have performed a digital makeover on fundamental aspects of Chinese consumers’ daily lives, they have set their sights on the industrial internet. They are delving into vertical and B2B markets, developing everything from product design and manufacturing to supply chain and logistics. Their efforts extend to nurturing the digital platforms that are poised to transform industries of all kinds.

Internet companies’ attempts to gain a foothold in the industrial sector were apparent in the ramp up of activity in 2018. Major internet players launched initiatives, such as the latest version of Baidu’s Apollo autonomous-driving open platform, which launched in July, and efforts by giants such as Alibaba to digitize more than 1 million mom-and-pop grocery stores. They were joined by startups like Luckin Coffee and BingoBox, which launched businesses that combine online and offline know-how in new ways. The trend also saw substantial investment in emerging internet leaders such as Meituan Dianping, which raised $51 billion in an initial public offering, and Didi, which secured a new multibillion-dollar round of financing. Another internet giant, Tencent, announced a restructuring to enhance its B2B capabilities and move to the industrial internet. Tencent CEO Pony Ma could have been speaking about the direction of the entire internet industry when he described the company’s initiative as marking “the start of the next two decades.”

A Strong Consumer Internet Is Driving the Development of the Industrial Internet

The rapid growth of China’s consumer internet has altered almost every aspect of daily life in the country of 1.4 billion. It has also produced massive amounts of digital data, tools, and know-how, which Chinese internet players are using to make inroads into the industrial internet. (See Exhibit 1.)

Just how much of daily life has been changed by digital innovations cannot be overstated. Examples in several areas make that clear:

- Clothing. Retailers are using agile digital-supply-chain management and data-based product-life-cycle management to speed up manufacturing while staying on top of fashion trends. Fast-fashion e-retailer Hstyle introduces 30,000 styles annually, 60% more than Zara, the Spanish retailer that helped pioneer the fast-fashion concept. Digital-enabled manufacturing and supply chain management allow Hstyle to accommodate minimum volume orders as small as 50 items.

- Food. More than 600,000 restaurants in 200 cities are fully digitized. They use QR codes, mobile ordering, and mobile payments to speed up seating, ordering, and payment.

- Housing. By 2018, some form of networked smart-home products could be found in about 20% of homes in large Chinese cities, catching up to the US average of 27%. As of Q2 2018, China accounted for 35% of smart speaker sales worldwide, only a year after those products appeared in the Chinese market.

- Transportation. In 2017, Didi’s technology-based ridesharing platform served 20 million riders a day in China alone, surpassing the 15 million riders that Uber carries a day worldwide. In addition, from 2014 to 2017, the number of vehicles in the country with connected-car services grew to 18 million, an average annual compound growth rate of 25%.

Chinese startups that blend online and offline operations in new ways continue to emerge. One is Luckin Coffee, which opened 1,700 locations in its first 11 months using online customer acquisition to boost offline sales. At its current growth rate, the company could surpass Starbucks as the biggest coffee chain in China by mid-2019. Another startup that’s had success with an online-offline business model is BingoBox. The chain of cashier-less convenience stores uses QR codes, RFID, and biometric recognition technologies to make it easy for customers to unlock the door, get what they need, and pay on their phones.

Chinese startups that blend online and offline operations in new ways continue to emerge.

An Industrial Internet Primed for Transformation

Unlike the consumer internet, China’s industrial internet lags behind that of other developed economies, making it ripe for growth. Only 25% of Chinese manufacturers have smart-factory initiatives, for example, compared with 46% in Germany and 54% in the US. Digging deeper, China trails global leaders in four key areas of smart manufacturing:

- Smart connectivity. China trails the US in investments in and use of interconnected machines, equipment, and sensors. By 2016, China’s investment in industrial sensors totaled around $3 billion, compared with the US’s $4 billion. The same year, approximately 5% of industrial sensors included smart sensors (those with integrated sensing, processing, and wireless communications features), compared with about 12% in the US.

- Data integration. Other developed economies remain ahead in adoption of industrial IT, which connects data from various internal systems—often through the cloud—in order to digitally reproduce manufacturing processes. As of 2018, one-third of Chinese enterprises use either private or public cloud services, compared with 80% of US companies.

- Smart decision making. China also lags behind other global leaders in using algorithms and distributed analytics to improve manufacturing equipment and processes. Of the Industry 4.0 patents that Chinese companies hold, only 10% cover smart data analytics and decision making, compared with 34% of US companies’ patents.

- Human-robot collaboration. The country’s adoption of advanced manufacturing technology, including smart machines that work with humans to perform heavy, repetitive processes, also is behind that of other large economies—but it is improving. By 2017, China accounted for 36% of all industrial robots sold worldwide, up from 21% in 2013. Still, the use of industrial robots remains relatively rare, with a penetration rate of 68 per 10,000 factory workers, compared with 189 in the US and 309 in Germany.

Such lags generally are attributed to a Chinese manufacturing sector that is young and still maturing. High-end manufacturing accounts for only 21% of the total, compared with 37% in the US. Chinese companies’ adoption rate for supply chain management, customer relationship management, and other industrial IT also trails that of their US counterparts. Chinese companies’ decision to prioritize the development of consumer products and services is another reason for the slow digitization of upstream production.

That is changing. Internet companies are making strides in emerging fields such as autonomous vehicle technology, where the number of Chinese startups valued at $100 million or more outpaces that in the US. In addition, total venture capital investments in emerging technologies in China top investments in similar US startups in areas such as unmanned aerial vehicles, voice recognition, and computer vision.

Already, Chinese emerging technologies are creating new business models and entire communities of interconnected enterprises. One of these new business ecosystems has formed around Baidu’s Apollo autonomous-driving open platform, which encompasses hardware, software, cloud services, and sample vehicles. The platform has attracted more than 130 partners, including original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), parts suppliers, and tech companies based inside and outside China, as well as more than 12,000 developers. In 2018, Baidu and King Long, a Chinese bus manufacturer, began volume production of a Level 4 autonomous bus based on the Apollo open platform. In 2019, the number of Apollo-powered vehicles is expected to exceed 10,000.

Such developments and the thriving consumer internet are bolstering China’s industrial internet. One example is Alibaba’s Tmall Innovation Center. The e-commerce platform collects purchasing and behavioral data from 600 million customers of Alibaba online services and aggregates and anonymizes it before making the information available to brand partners in order to target new products more precisely. To date, Tmall has helped incubate around 300 new products. Among them: a custom shampoo for P&G that sold 15 million bottles in a month, and a specially packaged Mars chocolate that sold 5,000 units in the first 12 hours it was offered. Another example of progress in the country’s industrial internet is the digitization of upstream production in the food and beverage industry undertaken by companies such as Meituan Dianping, China’s largest online food ordering and delivery service.

Digital Players’ Growing Presence in the Industrial Internet

Chinese internet companies are expanding into the industrial internet not just because they can but because they have to. Online user growth is slowing, forcing the companies to find new ways to expand. By 2017, year-over-year growth of new Chinese internet users hit a ten-year low of 5.6%.

Chinese internet companies are expanding into the industrial internet not just because they can but because they have to, as the growth in online users slows.

To make up for slowing consumer growth, Chinese internet players are using their extensive online holdings as a launch pad for vertical growth. The fragmented nature of the country’s offline retail market plays into this strategy. In 2017, China’s top 100 brick-and-mortar retailers accounted for only 7.5% of all offline retail sales. It’s not easy for the small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) that constitute the bulk of offline retail to scale. As a result, they are not as motivated to adopt digitized systems and instead could be interested in teaming up with a partner.

One sector where the presence of online players is apparent is the country’s grocery industry, which predominately comprises small, mom-and-pop stores. Since 2016, Chinese internet giants have introduced digital supply chains, logistics, and payments to these establishments. For example, Alibaba alone has converted 1 million mon-and-pop stores, about one-sixth of the total.

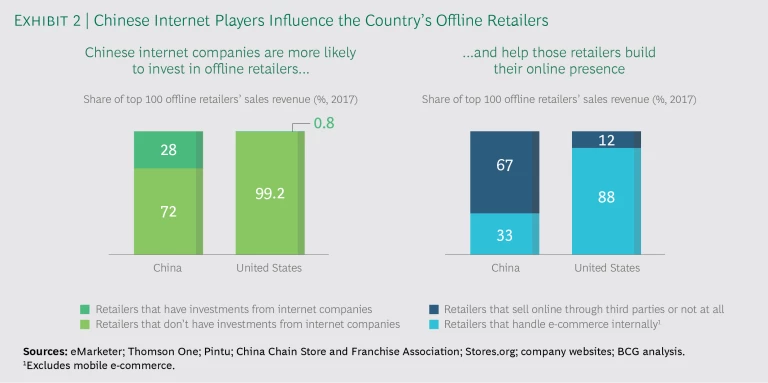

Another sign of internet players’ growing presence in traditionally offline businesses is the significant direct investment they’ve made during the past five years in larger brick-and-mortar retailers. From 2015 to 2018, China’s top five e-commerce players closed 15 investments in offline retailers, compared with one for US internet players in US retailers. Revenue for Chinese brick-and-mortar retailers that were targets of those investments totaled $101 billion, compared with a total of $16 billion reported by the US offline retailers that have received investment from US internet companies.

Clearly, Chinese internet companies’ strategy to invest in offline retailers differs from what’s happening in the US, where leading offline retailers prefer to build their own e-commerce presence rather than pair up with an internet partner. To date, China’s internet players have invested in companies among the country’s top 100 offline retailers that account for 28% of the group’s total sales revenue. By contrast, US internet companies have invested in retailers that account for less than 1% of sales registered by the top 100 US offline retailers. Although 88% of US retailers keep their e-commerce efforts in-house, only 33% of Chinese offline retailers steer their own e-commerce efforts. The majority choose to sell online either through a third-party e-commerce site or not at all. (See Exhibit 2.)

Pursuing a Platform Business Model

China’s internet players are using platform-based businesses as another option for entering the industrial internet. Platforms facilitate exchanges between various groups, such as consumers and producers or, in the case of B2B, manufacturers and suppliers. Platforms are especially well-suited to the Chinese economy since they can give SMEs the opportunity to digitize their operations.

Chinese companies run a significant portion of the global platforms that provide solutions to industry sectors, accounting for approximately 50. Among the players are industrial companies such as Haier Group, Sany Group, and XCMG Group; tech companies including Yonyou and Sysware; and internet companies such as Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent.

One example is Baidu’s open AI platform, which provides access to artificial intelligence (AI) services such as voice and image technology and natural language processing. The platform has been used in such diverse fields as agriculture, manufacturing, and health care, where it helped reduce the misdiagnosis rate for diabetes-related eye disease to less than 5%.

While internet companies in the US and EU have focused on building platforms to offer data and technology, Chinese companies’ platforms are more inclined to provide business solutions. Many of the platforms match SMEs with available resources. One example is Haier’s COSMOPlat platform, which the manufacturer of home appliances and other equipment created for its own use before opening it up to third parties. SMEs can use the platform to tap into supply chain and logistics resources. Outsiders’ use of the platform has increased to the point where around half of orders placed are for non-Haier clients.

While internet companies in the US and EU have focused on building platforms to offer data and technology, Chinese companies’ platforms are more inclined to provide business solutions.

Platforms are catching on because they make it easier for the Chinese SMEs that account for the vast majority of the country’s manufacturing base to go digital. Unlike in other large economies, manufacturing in China is fragmented. Using automotive manufacturing as an example, the top four Chinese manufacturers account for 32% of total sales volume, compared with 59% for the top four US automakers. For crude steel manufacturing, the top four Chinese companies account for 22% of total production, compared with 65% in the US.

China’s SME manufacturers face multiple challenges that make it difficult to digitize on their own. Among other things, they have a hard time getting credit and face an economic environment that keeps profits low, thus shortening their lifespan. Higher labor costs complicate the situation even further. From 2007 to 2017, manufacturing salaries rose 13% annually. As they struggle to stay in business, SMEs consider better policy and economic support, recruiting, and other improvements to be more important than going digital. Given the circumstances, having access to a platform to digitize operations could be a quick win.

Navigating the Next Phase of China’s Digital Evolution

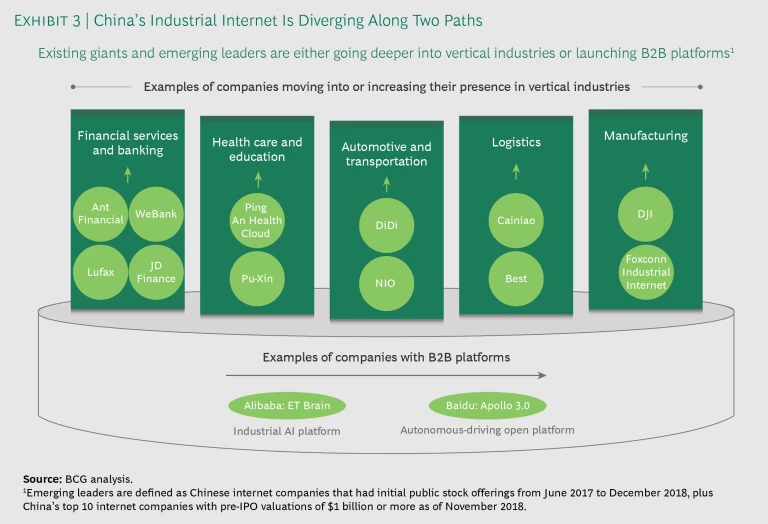

The effects of China’s digital evolution extend beyond the country’s internet companies. They also are impacting established companies in traditional industries and multinationals doing business in the country. To remain relevant, all three groups must be prepared to act to gain headway in the industrial internet or build B2B platforms. Recent investments in internet companies pursuing such strategies show what the payoff can be. Of the Chinese internet companies that either went through initial public offerings in the 18 months prior to the end of 2018 or became top 10 “unicorns,” with pre-IPO valuations of $1 billion or more, more than 70% were pursuing vertical industries or positioning themselves as platforms. (See Exhibit 3.)

But getting there won’t be easy, and the challenges differ depending on the entity.

Internet players must gain B2B expertise. To compete, internet companies must improve their understanding of how vertical industries operate and figure out how to combine that newfound knowledge with their technology expertise to help existing industry players go digital. For at least some of these companies, moving into the industrial internet could require adopting a B2B focus for the first time and determining the best organizational structure to accomplish that. For internet companies that have operated only as B2C businesses, such a transformation could involve a significant culture shift. Internet companies that target a specific vertical industry must decide the best way to do that, including evaluating how to create a business ecosystem around their efforts and determining if any existing industry players could become partners. Finally, internet players must decide whether building a platform is the best way to enter a given industry, and how they could use existing technology to do that.

Companies in traditional industries must discern the best way to digitize. For longtime industry players, the status quo is not an option. One way or another, digitization is coming. The question is how to deal with it. Chinese industrial heavyweights must decide if they would be better off digitizing on their own to compete with internet players or collaborating with them. If the latter, they need to take additional steps to map out what an equitable partnership would look like. Companies in traditional industries also must consider how to handle coming disruptions to their existing business ecosystems. As part of that, they should re-examine existing partnerships to decide if the agreements should be restructured, or if they should seek new partners. In addition to digitizing what they make and sell, traditional companies must remake themselves as digital organizations by borrowing best practices from internet players and adopting modern practices such as agile ways of working.

Multinational enterprises must develop a “China for China” strategy. Global companies must adjust their strategy for doing business in China to address new forms of competition. To start, they need to determine the most advantageous way to participate in the industrial internet. As part of that, they must build relationships with the country’s internet giants, taking into consideration the partnership models that offer the best value proposition. To counter competition from Chinese digital players, multinationals might need to make their Chinese operations as local as possible in order to respond quickly to changes in the market. A localized “China for China” makeover could involve changes to everything from management to hiring to product design.

From fast-growing startups to new ventures from established players, the developments of 2018 underscored how far China’s internet industry is advancing into traditionally offline businesses. All signs indicate continued movement in two directions, toward digitization of vertical industries and growth of B2B platforms. Regardless of the type of company and its current operations, the path forward will involve challenges and risks. Not the least of those is deciding how to reorganize to take advantage of new market dynamics, including whether to collaborate with or compete against other entities. Companies that develop a sound plan are more likely to ensure that their next act is a successful one.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit

Featured Insights

.