For 12 years, Yasmeen struggled to balance the demands of her job as a private driver in Cairo with her responsibilities as a mother of four. Now, as an Uber driver, she earns more money and has a flexible schedule that allows her to spend more time with her family. In Nairobi, Jomo was dismissed from his job as an unskilled technician in 2014. He now heads a ten-employee business selling mobile phones online to underserved populations in Kenya. Ngugi, also of Nairobi, earned a meager living selling everything from kitchen tools to phones through an online classified-ad platform. After he began selling on Jumia, a Nigeria-based online marketplace that reaches 14 African countries, his income increased tenfold. Ngugi also has two employees, lives in a bigger house in the central business district, and uses some of his earnings to provide health care and schooling to street children.

Across Africa, Jumia, Uber, Souq, Thundafund, Travelstart, and a host of other online marketplaces are starting to boost incomes, create jobs, and offer new opportunities for workers. Whether such platforms merely cannibalize the revenue of brick-and-mortar businesses and undermine job security is a source of heated debate in many developed nations. But in much of Africa, where the retail sector and formal labor markets remain underdeveloped, the potential downsides of the rapid expansion of online marketplaces are negligible—and the potential gains significant.

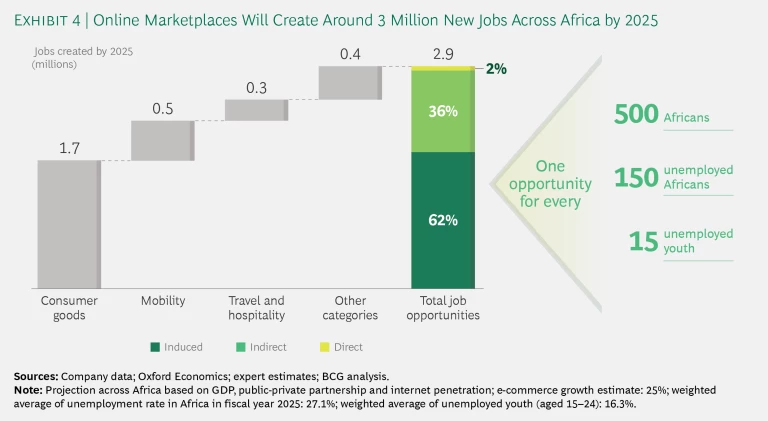

By our analysis, online marketplaces could create around 3 million new jobs, ranging from delivery drivers to retail and hospitality workers, across the continent by 2025. These businesses could also boost African economies by expanding the supply of goods and services, making assets more productive, and unlocking new demand in remote locations, which will boost consumer spending.

To ensure that online marketplaces achieve their full potential, governments need to create a healthy environment in which these businesses can not only thrive but also deliver inclusive economic growth in underserved regions and advance national development goals. We suggest a three-pronged approach that fosters a mutual understanding of both the opportunities and concerns of the public and private sectors, involves sharing of resources, and builds the right technological infrastructure and governance systems.

The Economic Potential of Online Marketplaces

Online marketplaces are digital platforms that essentially match independent, third-party providers of goods and services with customers. There are four basic business models for such platforms: business-to-consumer, business-to-business, consumer-to-consumer, and consumer-to-business. Platforms such as Jumia, Konga.com, and Takealot.com can serve as both B2C and B2B marketplaces. Classified-ad sites OLX and Avito are C2C platforms. South Africa’s Thundafund, a crowdfunding platform for entrepreneurs, is an example of a C2B marketplace.

Marketplace platforms operate within complex ecosystems that often span many countries. The typical ecosystem includes merchants, customers, and logistics providers, all of whom interact with one another. In Africa, online marketplaces also often employ field agents who recruit and train merchants and customers who are new to such platforms. Their role is mainly to remove friction among users unfamiliar with the online world. In the typical transaction, merchants offer their products and purchasing information through the online marketplace. After a customer searches the platform and purchases a product, the logistics partner delivers the product to the customer. Customers who do not wish to pay electronically in Africa often pay in cash upon delivery. If unsatisfied with the product, the customer ships it back to the merchant through the same logistics company and receives a refund. If the payment is made electronically, the refund is processed through the online marketplace.

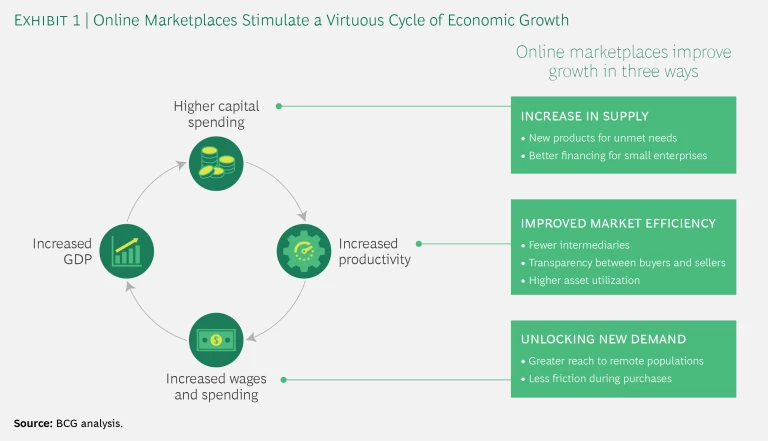

Online marketplaces can boost economies—especially in developing African nations—by improving market efficiency and increasing supply and demand. (See Exhibit 1.)

Improved Market Efficiency. Globally, there is a correlation between higher e-commerce penetration and how efficiently commercial transactions are made. There seems to be a clear difference in efficiency—based on “goods market efficiency” scores published by the World Economic Forum—between African countries in which e-commerce accounts for more than 0.5% of retail sales and those in which it accounts for less. Similar correlations between e-commerce penetration and labor market efficiency are found in the rest of the world, and they grow stronger as economies become more developed.

As has been shown in regions where online marketplaces have proliferated, these platforms improve market efficiency in several ways. For one, they reduce the number of intermediaries in commercial transactions by enabling merchants to sell directly to consumers. This is especially valuable to merchants in Africa, where conventional retail channels remain underdeveloped. Crowdfunding marketplaces, for example, allow entrepreneurs to bypass banks and other intermediaries when raising funds. Online marketplaces also make information on buyers and sellers more transparent, such as by indicating trustworthiness through the publication of reviews, reducing the time and expense required to verify the reliability of both parties. Hospitality marketplaces, which provide relevant information and reviews about both hosts and guests, also exemplify the value of online transparency. This is particularly important in Africa, where trust in online transactions remains low.

Online marketplaces also enable assets to be used more productively. Uber vehicles carry passengers for 30% more of the time they are on the road compared with conventional taxis, thanks to the company’s system for matching drivers and passengers, which reduces idle time, according to a 2016 study by economists Judd Cramer and Alan B. Krueger. Uber vehicles traveling the same distance over the course of a day as taxis also carry passengers 50% more of the time. The large scale and dynamic pricing models of such marketplaces help them more efficiently match supply with demand throughout the day. These tools are especially useful in regions where low population densities and limited traffic flow can depress taxi utilization rates.

Increased Supply. By creating new ways to reach customers and raise capital, online marketplaces significantly boost the supply of goods and services to meet untapped demand. Conventional hotels and inns, for example, are limited in Africa and can be too expensive for budget travelers. Airbnb creates new supply by enabling owners of apartments and houses to rent their residences to travelers who otherwise might not have booked an overnight stay. Such hospitality sites also open up new travel destinations without the need for heavy investment in a dedicated hotel infrastructure.

By creating new ways to reach customers and raise capital, online marketplaces significantly boost the supply of goods and services to meet untapped demand.

Small entrepreneurs are better able to raise the funds they need to start or expand businesses using online marketplaces, particularly in areas where access to capital is scarce. (See Exhibit 2.) In many African markets, merchants seeking loans can allow online marketplaces to share their data with financial institutions. Jumia, for example, has formed a partnership with mobile phone-based lender Branch to offer small instant startup loans to qualifying merchants selling on its platform. Uber also offers several types of financial assistance. It has announced partnerships with vehicle-leasing companies such as Easyway Leasing in South Africa and Nacita AutoCare in Egypt and with financial institutions such as Stanbic Bank and Barclays in Kenya, Bank of Africa and CRDB Bank in Tanzania, and Yako Microfinance in Uganda. Several crowdfunding platforms also serve online entrepreneurs in Africa. Thundafund, for example, helped raise more than $1.4 million in 2017, which funded more than 400 projects. Thundafund founder Patrick Schofield has also recently launched Uprise.Africa, a crowdfunding service for small businesses seeking to raise from $400,000 to $6 million.

Increased Demand. Many skeptics of online marketplaces contend that purchases add little or nothing to the economy because they merely cannibalize the sales of brick-and-mortar retail channels. But recent evidence suggests that online marketplaces mainly generate incremental sales growth, even in developed economies. A BCG survey conducted in a European capital found that a mere 19% of ride-hailing trips represented cannibalization from taxis.

Gauging the Economic Impact on Africa

We believe that the economic benefits of online marketplaces will be amplified in Africa—and that the potential downside risks to established businesses and workforce norms are low. This is largely because many of the continent’s economies and formal job markets remain underdeveloped.

First, it is important to consider that Africa still has enormous untapped market potential. While GDP growth averaged 1.7% in the US, Europe, and Japan from 2007 through 2017, economies that the World Bank classifies as low-income, such as Ethiopia and the Republic of Congo, as well as upper-middle-income nations such as Botswana and South Africa, grew in the 7% to 8% range over that period. The GDP of Africa as a whole will continue to grow 3% to 4% annually through 2023, the International Monetary Fund projects.

Africa’s retail sector is also very underdeveloped. For perspective, consider that as of 2018 there were 136 physical retail stores per 1 million inhabitants in Latin America, 568 per million in Europe, and 930 in the US. In Africa, there were fewer than 15 formal retail stores per million people. This extremely low penetration suggests that e-commerce has only a minimal chance of displacing existing sales in the formal retail sector.

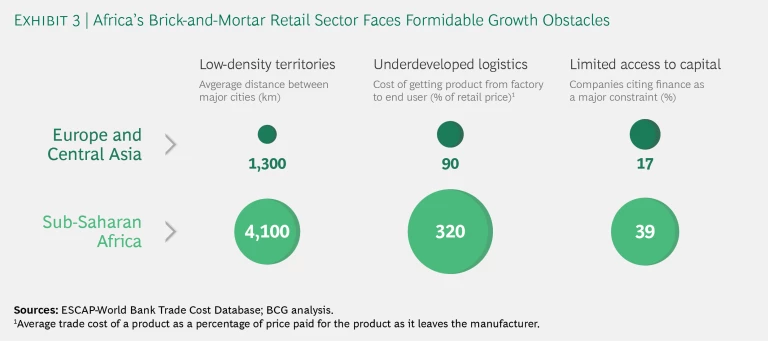

The region’s geography, sparse transportation infrastructure, and thin capital markets inhibit rapid expansion of brick-and-mortar retail. (See Exhibit 3.) Whereas in Europe the average distance between major cities is 1,300 kilometers, in Africa it is 4,100 kilometers. The cost of getting a product from the factory to an end user within Europe adds around 90% to that product’s manufacturing cost. In Africa, logistics add an average of 320% to a manufactured good’s cost. In Europe, 17% of companies cite access to finance as a major constraint to their business, while in East Asia just 11% of companies cite financial access as a constraint. In sub-Saharan Africa, 39% of companies complain of limited access to finance.

Big Informal Labor Market. In developed economies, where labor laws and regulations are clearly defined to fit a historically validated model, the rise of online platforms has disrupted labor markets by blurring the lines between employees and freelancers. In Africa, however, the vast majority of workers are in the largely undocumented informal sector. Seventy-one percent of Nigerian workers are self-employed, for example, and another 9% contribute labor as family members, according to the International Labour Organization. The IMF estimates that the informal economy accounts for 38% of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa. As a result, much of Africa is in a position to essentially develop from scratch labor norms that align with the needs of online employees and employers. In the long run, bringing more people into the formal workforce will help governments enforce regulations, better measure economic activity, and improve taxation. For workers, formal employment will provide the documentation they need to take out mortgages and personal loans and to verify their skills and experience.

How Online Marketplaces Create Jobs

Generating employment is an urgent priority for all of Africa, where the population is projected to reach 1.5 billion by 2025. The African Development Bank estimates that one-third of the 420 million Africans from 15 through 35 years old were unemployed as of 2015. That figure jumped to 85% when the “vulnerably employed”—those working in the informal sector—were included.

Our research indicates that online marketplaces will create around 3 million new jobs in Africa by 2025—roughly one for every 150 unemployed Africans or one for every 15 unemployed workers aged 15 to 24. (See Exhibit 4.) Our estimate is based on current direct, indirect, and induced employment in online marketplaces in the region as well as the current and projected revenue of these marketplaces. It is also based on our own bottom-up estimate of online marketplace revenue and assumes 25% to 30% annual revenue growth through 2025, which is in line with historic trends and growth rates recorded in other regions.

We estimate that the number of Africans directly employed by online marketplaces—workers such as platform developers and operations and marketing personnel—will reach around 100,000. Indirect employment generated by marketplaces, including workers such as merchants, logistic clerks, passenger-vehicle drivers, hotel staff, and housekeepers, will amount to 1 million more jobs. An additional 1.8 million jobs will be “induced,” or created through the additional economic activity stimulated by online marketplaces. Occupations affected will include car mechanics and cleaners, tourist guides, and craftspeople. The biggest employment gains will come in the consumer goods sector, where online marketplaces are projected to account for 58% of jobs created—direct, indirect, and induced—by 2025, followed by mobility (18%) and the travel and hospitality sector (9%).

The economic activity generated by online marketplaces can boost employment and incomes in several ways. It can create entirely new jobs, stimulate skills development programs, and increase demand for goods and services in locations currently beyond the reach of conventional retail networks. It can also bring new people into the formal workforce, such as women and youth, who in some countries have been excluded from the labor market.

The success of Kenyan vendor Ngugi illustrates how online marketplaces create new job opportunities by opening new markets for merchants. Before he started selling on Jumia in 2014, Ngugi offered a wide range of goods through classified ads, earning around $250 a month. Since joining the online marketplace, he has seen orders grow from 30 items a week to 70 a day and his monthly income rise to $2,500. Ngugi also opened a retail store in Nairobi to sell products to buyers who don’t feel comfortable making purchases over the internet. Ngugi’s two employees, meanwhile, now also run their own offline shops in addition to working for him.

A good example of how online marketplaces can boost employment by upgrading skills is provided by Jomo, the Nairobi mobile phone vendor. After losing his job as a low-skilled technician, he saw a business opportunity in selling phones and accessories online to young consumers in Nairobi and rural areas—a major underserved market. Jomo used digital and business management skills he acquired through online and offline courses to expand his business by adding after-sales services. He also opened a retail store in Nairobi and now has ten employees.

The experience of Egyptian Uber driver Yasmeen shows how online marketplaces can make it easier for women to enter the workforce and build their own businesses. When it proved a challenge to balance her duties as a mother of four with her work as a personal driver for parents she met at her children’s school, Yasmeen’s first impulse was to stop working. But with Uber, she now has a flexible schedule that allows her to spend more time with her children. She has also used her Uber income to acquire six cars that she rents to other drivers and has persuaded her husband to join the family business. Now a well-known figure in her community, Yasmeen has inspired several other mothers to become Uber drivers.

Digital platforms can make it easier for women to enter the formal workforce and to build their own businesses.

The Challenges Facing Online Marketplaces in Africa

Despite the economic promise of online marketplaces, both the public and private sectors see a number of hurdles facing these platforms. Executives we interviewed at online marketplaces operating in Africa cited four primary impediments that must be overcome before these businesses can achieve their full potential.

Underdeveloped Infrastructure. Major improvements in communications and transportation infrastructure are essential for online marketplaces to fulfill their potential to create jobs and boost economic growth. Despite dramatic growth over the past decade, only around 20% of people in sub-Saharan Africa are connected to the internet, leaving the great majority of consumers unable to shop online at home or make electronic payments.

Even when online orders are placed, inadequate roads and rail links between cities, let alone remote villages, make it very difficult to reliably get goods to consumers—especially over the so-called last mile to buyers’ homes. Poor coordination of distribution networks is another problem. As a result, some online marketplaces report that 30% to 40% of products ordered are returned because delivery services cannot find the destination. In India, which also struggles with poor infrastructure, some online marketplaces are seeking to address such obstacles by operating their own logistical services in major cities and forming local partnerships in smaller ones. In Africa, logistics startups such as Ace and Exelot are also seeking to resolve bottlenecks in last-mile delivery to customers. But significant investment in roads is still required.

Lack of Regulatory Clarity. The current regulatory environment is blurry for online marketplaces in Africa. In many countries on the continent, the legal framework for e-commerce is in its infancy, and guidelines for data privacy, consumer protection, and online payments have yet to be implemented. As a result, many consumers distrust online transactions, fearing fraud or misuse of data. Distrust of e-commerce among policymakers also remains high. Some African governments are wary of opening traditionally closed sectors to online competition, as incumbents warn that online marketplaces will harm their businesses. While caution is understandable, the magnitude of the problem claimed by some parties is often unsubstantiated. Despite this, the entry barriers for online marketplaces remain high on much of the continent.

Illiteracy and Inadequate Digital Skills. Despite the rapid growth in mobile phone subscriptions, many Africans lack access to online platforms. With high illiteracy rates in some African nations, many consumers in the region cannot understand online content or use digital technologies to make transactions.

Digital illiteracy among African consumers and vendors presents a number of obstacles to growth in online commerce. Merchants lack the knowledge needed to adapt their value chains to the digital world. And online marketplaces must often look outside of Africa for the digital marketers, data scientists, user interface and user experience designers, and other skilled workers they need to succeed. Several online marketplaces as well as a growing number of public-private initiatives in Africa offer training programs to address the digital talent shortage. Jumia, for example, offers online training that includes video tutorials and tests in topics such as pricing, search engine optimization, stock management, and order fulfillment. In other countries, local education institutions, such as the 1337 School in Morocco, which specializes in teaching computer programming, are offering innovative formats to bridge the digital skills gap. Such initiatives are not yet sufficient, however, to meet the region’s vast skills needs.

Access to Funding and Markets. As noted above, a high percentage of small enterprises and entrepreneurs in Africa report that limited access to capital seriously constrains their ability to expand into online marketplaces. Of all the funds raised for e-commerce in Africa, 90% are concentrated in just five countries—Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and South Africa—according to the World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA). Borrowing funds through formal financial institutions to purchase vehicles or carry inventory, for example, is difficult. While some online marketplaces offer their own financing for merchants, greater progress is needed in making formal financial markets accessible to small enterprises and to attract foreign direct investment. Indeed, around 40% of African nations do not even have FDI promotion agencies, according to WAIPA.

While some online marketplaces offer their own financing for merchants, greater progress is needed in making formal financial markets accessible to small enterprises.

Gaining access to markets can also be challenging in much of Africa. The region’s highly fragmented markets and heterogeneous legal frameworks make it difficult for online marketplaces to build scale. The great differences in customs, practices, and habits, meanwhile, mean that suppliers must adapt their value propositions to many local markets.

Challenges Online Marketplaces Pose for African Governments

The expansion of online marketplaces also poses difficult challenges for governments in Africa. These concerns include the risk of losing regulatory control, protection of personal data, the potential disruption of employment norms, and the threat to traditional business subsectors.

Loss of Regulatory Control. Many nations lack clear frameworks to govern e-commerce. Policymakers in these countries worry that online marketplaces could pose challenges to their financial oversight, taxation, and regulatory systems. Many African policymakers are unsure of how to handle income generated by online merchants and marketplaces. Should they tax merchants or the platforms, for example, and how can they ensure that marketplaces are treated fairly compared with brick-and-mortar businesses? Should taxes be assessed on the basis of the final price of a good or service or on the value added by each individual party? Or should policymakers apply a flat tax or a rate that depends on the maturity of the online business so as not to inhibit the growth of new sectors? It is also unclear which parties are liable in disputes, how to protect consumers from fraud, and how to check whether merchants and marketplaces are complying with established norms and standards.

Personal Data Protection. Gathering and using customer data is at the core of online marketplaces’ business models. Many policymakers are concerned about how confidential data on their citizens and businesses is handled. Is data processed inside the country, for example? Is it stored abroad and processed by subcontractors? Crucial financial data, for example, may be beyond the control of or inaccessible to central banks. A number of high-profile cyberattacks have also heightened concern over data safety.

Disruption of Employment Norms. Governments are concerned about how online marketplaces may transform their nations’ workforces. Online marketplaces are altering traditional employment structures and redefining roles and responsibilities, which raises the question of whether these businesses provide sustainable flows of work, as well as whether their workers receive the training or career opportunities they need for the long term. Another concern is that online marketplaces that rely on computer algorithms rather than human interactions to determine pricing, work assignments, and evaluations may deprive merchants of the power to make or challenge decisions that affect their businesses.

Impact on Selected Traditional Business Subsectors. In many African economies, certain traditional business subsectors are protected from competition, receive government incentives, or are tightly regulated. Policymakers are concerned that online marketplaces could disrupt these domestic equilibriums. The taxi industry is highly regulated in many African nations, for example. Online mobility marketplaces, policymakers worry, could avoid these regulations. There is also concern that these new businesses could cannibalize the taxi industry. Ride-sharing platforms could lure away drivers and, fueled by cheap venture capital money in the customer acquisition phase, offer unfairly low prices, distorting the traditional balance between supply and demand. Governments even worry that such disruption might lead to social unrest among displaced businesses and workers.

The “USB” Approach to Win-Win Online Marketplaces

To resolve the obstacles and concerns that constrain online marketplaces, both the private and public sectors will have to work together to develop an environment in which e-commerce can become a win-win proposition for the online marketplace community and the region’s governments. The place to start is by building mutual trust. We recommend a three-pronged approach that we have dubbed “USB,” which stands for understand, share, and build. (See Exhibit 5.)

By understand, we mean that the public sector and online marketplace communities should engage in discussions to achieve a common understanding of the opportunities for job creation, skill development, and inclusive growth. Both sides also must clearly understand each other’s concerns and needs—as well as the impact that can be achieved by addressing them.

The sharing of certain data, actions, and benefits is essential to establishing a spirit of trust and collaboration. Online marketplaces could share aggregated, anonymous data that is beneficial for urban development, for example. Shared actions could include a system for certifying that merchants are complying with the right standards, laws, and regulations. Online marketplaces and the public sector could also take collaborative actions to ensure that opportunities are shared with all segments of the population, including people who are sometimes excluded in the offline world.

Online marketplaces and government organizations can then work together to build a healthy digital environment by taking actions that remove the hurdles facing online marketplaces and alleviate the concerns of the public sector. For example, they can collaborate on skill-training programs and on developing technological infrastructure, such as digital identity systems, that ensure transparency on marketplace platforms.

The public and private sectors can also build a co-regulation framework that balances social and political risks with the promise of the value that online marketplaces can create.

The low level of online marketplace usage across Africa means that considerable work must be done at many levels to ensure that these platforms fulfill their potential to become an important source of new jobs. This promise relies on the ability of the private and public sectors to come together and collaborate to create the right digital environment. Instead of being seen as forces of chaotic disruption, online marketplaces should be allowed to develop in an environment that is designed from the outset to bring economic and social benefits to all.