Across industries, quality is back at the top of the executive agenda. Many executives have been spurred into action by prominent cases of quality mismanagement, including those involving leading automotive OEMs and steel producers, and by evidence of their own organizations’ persistent quality problems. The result has been the strongest revival of interest in quality since the emergence of “total quality management” tools three decades ago.

The recent spike in high-profile quality incidents has occurred despite many years of heavy investments in quality management systems, processes, and IT. These investments held the promise of securing and consistently improving the quality of operations. So what went wrong? Simply put, many organizations have become proficient at ensuring quality by “checking boxes,” while ignoring the imperative to make quality an integral part of the corporate culture.

To rapidly improve their company’s quality maturity, executives need a new approach—one that brings the rules to life and hardwires quality, as a paramount value, into the organization’s DNA. Leaders must adjust the context in which they and their employees work, so that everyone in the organization makes an affirmative choice to adopt quality-driven mindsets and behavior.

Many organizations have become proficient at "checking boxes," while ignoring the imperative to make quality an integral part of the corporate culture.

Transforming quality from a compliance exercise into a way of working typically requires a multistep journey led from the C-suite. Although completing the program may require two to four years, companies can generate tangible benefits within months.

Step 1. Raise Awareness of the Consequences of Poor Quality

No leadership team can avoid putting quality at the top of its agenda. Fulfilling this imperative begins with establishing a common understanding of quality. All too often, organizations think of quality solely in terms of meeting specifications for products or services. To integrate a quality mindset into the fabric of daily work, an organization needs a customer-centric definition of quality that is linked to delivering the corporate vision and strategic goals. This definition could be as basic as “quality means consistently giving our customers what they want, when and how they want it.” Such a definition recognizes the inseparability of quality leadership and industry leadership.

Members of the management team must be motivated to apply the definition of quality in their own work and ensure that all levels of the organization know the definition and apply it. To generate awareness of the consequences of poor quality, the executives driving the effort should share insights from quality incidents that have occurred both within the company and at other companies. It is particularly important to highlight the risks that exist within the company, such as those identified in quality audits. Managers should understand their legal responsibilities and the potential consequences of failing to meet them, including personal liability. For example, several managers of a Japanese steel company were indicted following a scandal involving the falsification of data related to product quality.

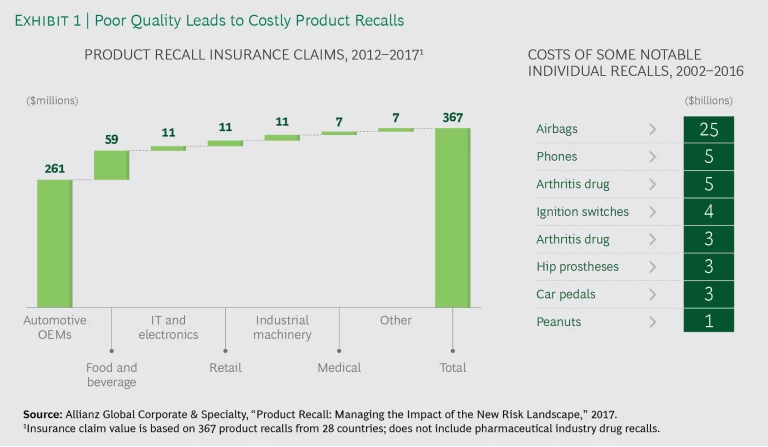

Awareness-raising efforts should also emphasize the financial impact of quality incidents. The high costs of product recalls arising from quality deficiencies are especially obvious. (See Exhibit 1.) These costs are incurred by companies across industries, although the automotive industry suffers the most.

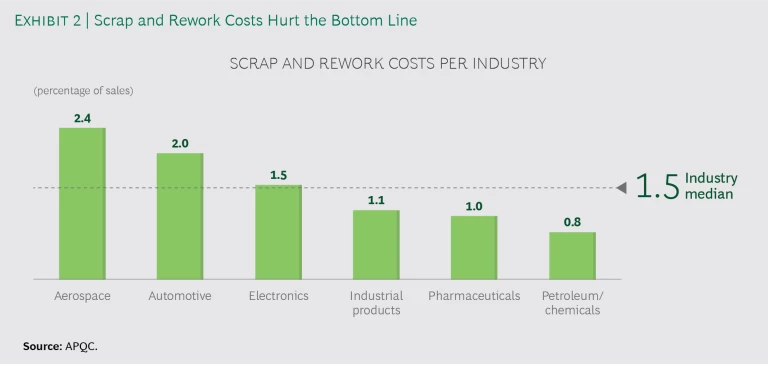

Additionally, costs related to production inefficiencies, increased downtime, and rejected products have a substantial impact on profitability across industries. In the automotive and aerospace industries, for instance, the costs of scrap and rework represent approximately 2% of sales. (See Exhibit 2.)

Step 2. Understand the Status Quo

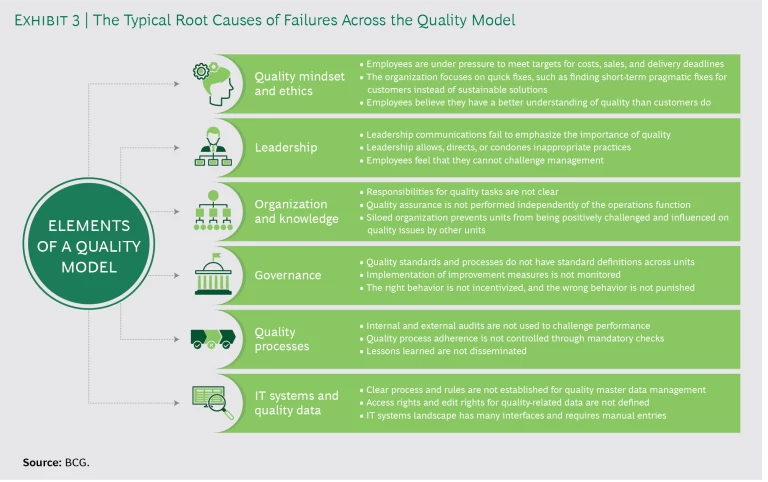

To set the stage for taking corrective actions, the management team must systematically identify the internal root causes of poor quality and recognize the gap between the expected and current state of quality maturity (that is, how well quality is embedded in the organization and its culture, processes, and IT systems). It can then establish a common understanding of the improvement priorities. An assessment of the current state typically includes the following:

- Advanced Analytics. The company should systematically screen for indications of potential quality problems (such as anomalies in operational measurements or unexpected adjustments of specifications). Advanced analytics lifts quality management to the next level by providing new methods to generate insights into potential problems. Companies can apply advanced analytics to data from business warehouse systems, test protocols, and customer complaint databases.

- Health Check. To understand quality mindsets and challenges, the company can conduct interviews (known as “beliefs audits”) with 10 to 20 senior managers. It can also use a quality maturity assessment to gain insights into the current state of its quality system. An additional in-depth analysis is required to identify the root causes of quality problems. In our work with companies in a variety of industries, we have identified typical root causes of poor performance across the elements of the quality model. (See Exhibit 3.)

Benchmarking. The company can complement the internal perspectives provided by the health check by benchmarking its practices against those of companies that have set the standard for designing organizations and cultures that promote quality.

Step 3. Design a Target Quality Model and Transformation Program

The root causes and gaps identified in step 2 provide the basis for identifying the most important requirements of the company’s quality model. The model should describe in detail the target state of quality maturity. To achieve the target model, the company needs a quality transformation program that defines the necessary improvement actions and a roadmap for implementation.

Companies need to ensure visibility into, and the independence of, important aspects of quality (such as standard setting and auditing) and provide the appropriate level of central oversight and governance. To that end, many will need to adjust their organizational structure.

Successful companies make distinct choices about organizational structure based on their culture. Organizations that start with a weak quality culture typically need a central quality team with strong enforcement power to define and bring to life the new model. Addressing quality issues at the local level may not be effective if a commitment to quality is not yet instilled in the culture. Indeed, at most companies that excel in quality today, a central team drove the transition from a weak to a strong culture. For example, at a company in a process industry, transitioning to centralized management of quality was a key mitigation step after a highly publicized quality scandal. In contrast, organizations in which employees are already highly committed to quality may choose a self-organized approach, with local teams directing the adoption of the new model.

A quality journey requires cross-functional participation, with all relevant stakeholders involved from start to finish. A central quality department is typically best positioned to coordinate the program and connect the various stakeholders. The department should become a promoter of culture change—driving organization-wide communication and providing training and engagement programs. The department should also oversee quality performance and track the implementation of improvement actions.

In addition, companies need to establish stringent quality assurance and control processes that are supported by an effective IT infrastructure. Sound internal auditing processes can substantially reduce the risk of major incidents. Such processes enable the early identification of inadequate practices or weak control systems in decentralized business units. They can also be a powerful engine for change, as long as the audit teams are regarded as a partner to the business rather than a policing function. In the best case, the audit teams identify concrete improvement opportunities and share them across the organization. To be effective, auditing processes need to be independent from the business and supported by end-to-end quality workflows. Such workflows connect all steps along the company’s full value chain and break down silos between the different steps. IT plays a vital role by creating data transparency, securing the integrity of the data, and fulfilling requirements for legal documentation.

At most companies that excel in quality, a central team drove the transition from a weak to a strong culture.

Step 4. Demonstrate a Personal Commitment to Change the Context

Quality policies, principles, standards, and codes of practice by themselves do not change behaviors. To be effective, a cultural transformation must start by addressing the context within which people work. Employees’ mindsets and behaviors will evolve to conform to the new context.

In particular, leaders must “walk the talk” on quality by demonstrating personal commitment and engagement and standing up for quality when incidents occur. Using the platforms provided by the quality department, they need to generate tailwinds for quality starting on day one of the transformation. Particularly effective examples of leading from the top include the following.

Engaging in Site Walks. Senior managers should periodically visit production sites and engage in positive conversations with employees about quality. By being present on the shop floor and talking about quality, leaders can help instill the importance of quality in the minds of employees, as well as demonstrate their personal commitment. A leading company in a heavy industry, for example, conducts “senior management quality tours” of production sites, so that leaders can have regular conversations with employees about the importance of quality. Such conversations are much more effective for instilling a quality culture than talking about quality only in the aftermath of an incident.

Initiating a Train-the-Trainer Cascade. Quality awareness training should cover much more than the technical and compliance aspects of quality. It must also address behavioral, ethical, and collaborative aspects, as well as customers’ perspectives. A workshop is the best format for such discussions.

To enhance the dialogue and ensure that all organizational levels are engaged, the company should roll out quality awareness training through a train-the-trainer cascade. Such a program begins with professional trainers instructing company leaders on quality topics and training techniques. These leaders train a larger group of employees, who then may train another group, and so on. Many companies have found that, compared with traditional methods, this is a rapid, cost-effective way to roll out quality training across the organization and improve skill retention.

Leaders must "walk the talk" on quality by demonstrating personal commitment and engagement and standing up for quality when incidents occur.

Using Digital Media. The company can use digital media to support its effort to embed quality in the culture. For example, the train-the-trainer cascade can make use of online courses. To raise awareness and extend the reach of its training program, a metals company uses “e-learning” modules covering quality topics such as testing, certification, auditing, and catering to customer needs. Social media can also be effective. A heavy-industry company has created social media platforms on which employees can discuss quality topics, including a chat group that has seen high levels of engagement.

Jointly Shaping the New Approach to Quality. Leaders should participate in the process of defining the new approach to quality. This participation often includes collaborating with quality experts to develop and disseminate new quality policies and standards. Leaders’ participation helps them appreciate the work of experts and allows them to integrate their points of view into the new approach. Their buy-in and support helps ensure that new rules do not become “paper tigers.”

Reviewing Quality Performance. Leaders should participate in regular review cycles that track quality KPIs and progress toward implementing improvement actions. In addition to traditional output-oriented quality performance indicators (such as customer complaint rates or cost of poor quality), best-practice companies track early-warning indicators (such as the rate of nonconformities detected in audits). They also track leading indicators of sustainable quality excellence. These include participation rates in quality training sessions, the number of quality site walks conducted by senior management, and the deployment rate of new quality standards. Tracking these KPIs allows a company to identify the need for an in-depth examination of weak spots and pinpoint areas for improvement.

Establishing Quality Task Forces. The company should prepare a detailed action plan to guide the rapid ramp-up of a team that can respond to severe quality incidents. The team should include members from the quality function as well as experts from other functions affected by the incident, including the legal counsel and the public relations department. The team must have access to the resources and expertise required to effectively respond, so that it can fulfill legal obligations and internal compliance standards while minimizing the impact on the company. Drawing upon expertise from different business functions, the company should create procedures and step-by-step guidance for how the organization should respond to quality incidents that are discovered internally through audits or whistleblowers or externally by the media or government authorities.

A well-designed program for a fast quality turnaround will significantly enhance individual awareness and ownership of quality and set the stage for the journey to quality excellence. It is essential to focus on culture as the context for quality, rather than just promulgating standards that define the content of quality. Considering that a quality issue can have catastrophic consequences for a company, no leadership team can afford to take a wait-and-see attitude to achieving quality excellence.