Imagine this: You have a health crisis. You pull up the health app on your phone and dictate your symptoms to an AI assistant. Then you are quickly connected via video chat to a coordinator in your health system who consults with specialists and comes back to you with a customized prescription on the basis of your medical history and personal genomics. Your tailored treatment is “manufactured” at a nearby lab and delivered to your workplace via drone—all before you’ve left the office for the day. Far-fetched as this may seem to many incumbent payers, providers, and health services companies, this scenario could soon be a reality.

Of course, industry shakeups are nothing new. But this time the disruptive forces barreling toward the health care sector are different. In the past, incumbents could rely on the fact that new entrants faced high barriers to entry: the extreme complexity of managing the cost of care and the highly regulated, capital-intensive, and very low-margin nature of the sector. Players with strong local-market positions and relationships with key stakeholders—from employers and physicians to regulators and policymakers—largely won out regardless of the challenge. Entering this space used to be akin to scuba diving without a tank. Not anymore.

Consumer-friendly tech giants have set their sights on health care. They don’t yet command the landscape, but their disruptive power could bring dramatic changes. And if adversity strikes the market, it could create just the opening these formidable companies need to gain a foothold over sleepy incumbents. Meanwhile, medical advances and new forms of treatment will demand alternative business and reimbursement models. True, a handful of savvier existing players—such as those in the US Medicare Advantage market —have been building up capabilities to meet these new disruptive forces, establishing models that will be hard to dislodge.

Consumer-friendly tech giants have set their sights on health care.

Yet many others are asleep at the wheel or, worse, sinking vast amounts of time and capital into capabilities that do little to future-proof their businesses and instead put them in an even more vulnerable position.

Not Your Usual Adversity

Historically, adversity in the health services industry has been caused by economic downturns and changes in the regulatory and legislative environment—which in turn have driven bad debt, led patients to defer elective procedures (and sometimes even preventive care), and increased the number of uninsured. These threats will not disappear. But as medical advances and the growing presence of tech giants reshape the sector, what it takes for incumbents to weather the next storm will look very different.

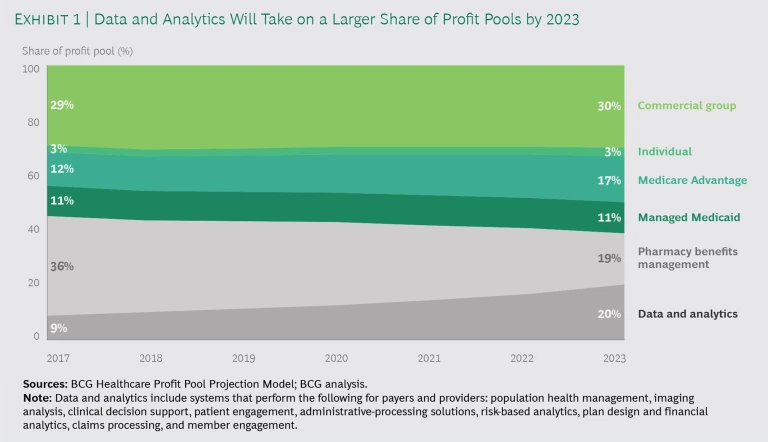

In the future, the impact of recession and legislative changes may be more muted and profit pools will shift. As an example, we see new profit pools, such as data and analytics, supplanting the more traditional insurance segments. (See Exhibit 1.) In a recession, we expect government to be the key source of funding for the sector. In the US, for example, this puts at a relative disadvantage those payers and health systems whose strategy is to chase commercial business for the higher fees, while players pursuing members of government-sponsored health plans will likely see a boost to their business. Sweeping legislative changes such as Medicare for All or the creation of Medicare buy-in options for older adults who have not yet reached Medicare eligibility age could accelerate this trend, resulting in a substantial expansion of government-funded health care.

Of course, while legislative changes could be highly disruptive, the direction they take will depend on the outcome of the 2020 US election. Regardless of political shifts, however, medical advances and changes in the nature and cost of cures will have a significant impact on health care business models, threatening to upend the viability of year-to-year care financing, disrupting the essence of what payers and providers do. For local plans and pure plays by lines of business, survival will be all but impossible.

Weathering adversity will be made harder by the advent of expensive new treatments and care that the traditional system will struggle to pay for and supply. Only a few providers are currently able to deliver these types of treatments. As more come online and demand for them grows, those who can’t provide this new type of care may be left by the wayside.

Over the long term, new treatment paradigms, such as cell and gene therapy and customized treatments, will disrupt the demand for and delivery of care. Some will require a break from annual insurance cycles and a shift to population-based drug and therapy reimbursements. Indeed, the advent of expensive but life-altering treatments—costing from hundreds of thousands to, in some cases, millions of dollars per patient—will require new constructs that enable payment to manufacturers over many years, pooled risk sharing across multiple payers (given the churn among customers), and outcomes-based guarantees from biopharma companies.

Another existential threat to the payer business model is the rapidly advancing understanding of genomics. This means payers will likely have to fund—and providers will have to treat—patients who are in a state of “predisease.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has already certified three Tier 1 conditions for which advanced screening and even surgery can be performed in the absence of any indication of illness, on the basis of an individual’s genetic makeup. These include hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, Lynch syndrome, and familial hypercholesterolemia. As such conditions multiply, the year-over-year funding mechanism that fuels payer profits may begin to break down.

Then there’s the power of the tech giants to disrupt. As these companies make a rapid entrance into the sector, they bring with them new business models and access to diverse sources of capital. Moreover, given their ability to build trust with consumers and harness their data to create scale—something that payers and providers have struggled with—they are well positioned to compete in the business of health care delivery.

It’s easy to imagine the scenario. A large tech giant invests in building a consumer-directed electronic health record (EHR) on its digital platform and offers it to payers, providers, and patients free of charge. As this platform becomes the primary method by which consumers choose health care, the company starts buying payers to round out its financing and actuarial capabilities. It then partners with a leading online retailer’s drone and drug distribution division to deliver treatments to consumers. Traditional payers, providers, and health systems cannot compete.

Your Playbook Needs an Upgrade

Medical advances and the presence of tech giants are not the only reason health care incumbents need to reexamine their strategies. In the past when adversity hit, usually because of an economic downturn, the standard playbook of incumbent responses was well known: cut costs by 5% to 10%, centralize and modernize functions to increase efficiency, and use those who can pay to subsidize low-margin populations. When payers and providers were competing only with one another, these tactics worked. In the next downturn, however, they are likely to be competing for customers with new entrants to the market. Yesterday’s playbook will still have a role—but it won’t be enough on its own.

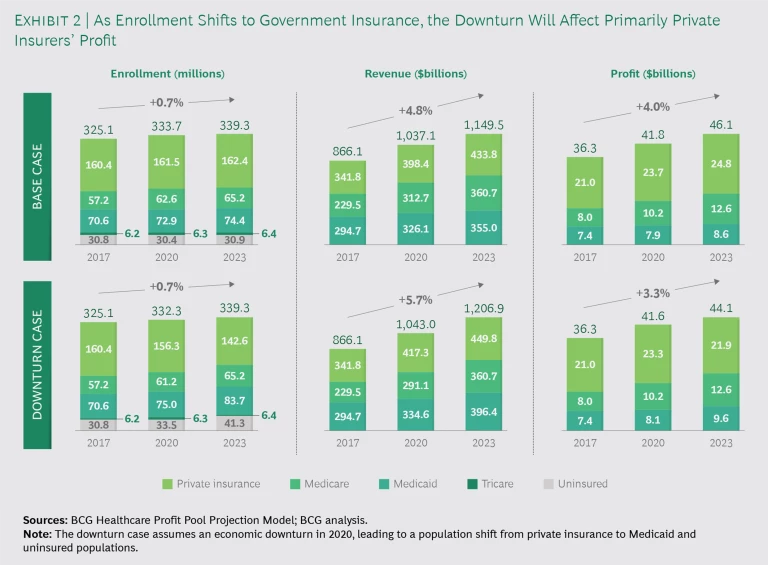

In a world where employer-sponsored insurance is shrinking in volume and becoming more susceptible to negative economic forces, cost cutting will no longer work as a backstop during a recession. Shifting insurance pools from private health insurance to government insurance results in lower industry profits, even when the overall pool of enrollees and revenue grows larger. (See Exhibit 2.) Achieving scale will become more important as cost pressures increase. And while some in the business of financing care and delivery have attained scale, their margins are razor thin. Diversification will therefore require moving into new markets, even those beyond care delivery.

Part of this shift involves forming partnerships and making acquisitions. Providers will need to integrate hospital and physician groups and diversify into outpatient settings such as ambulatory surgery centers and infusion services (walk-in outpatient centers treating acute and chronic disorders). Payers and providers will need to move outside their comfort zone and start to deliver what are becoming the essential building blocks of health care, from analytics and genomics to real-world evidence.

Transforming the cost base will take more than incremental changes. It will require a fundamental shift in the way both care and the business itself are organized. This means rationalizing administrative and delivery infrastructures to enable scale and aligning service lines and care settings to minimize redundancy. Moves to lower-cost settings should also be considered, particularly for patient-facing clinics, where these are essential to maximize throughput and quality.

Transforming the cost base will require a fundamental shift in the way both care and the business itself are organized.

In making this transformation, no stone should be left unturned, from developing best-in-class procurement to embracing the digital age, integrating EHRs with clinical decision-making processes, and creating an agile workforce. Anything that lies outside the enterprise’s core competency can be outsourced.

This means rethinking capital allocations. It involves moving away from making heavy investments in underperforming capabilities, legacy systems, and physical IT infrastructure—and away from investing in areas where the enterprise has no expertise, such as hospital systems building software. It’s also wise to avoid investing in retail and physical locations without a clear strategy on how to compete in a world where consumers increasingly prefer to access services online and on demand, whether at home, at work, or on the road.

These core transformations will be not only expensive but also organizationally difficult for incumbents to execute. Labor is one of the largest cost components of the system, and health care companies are also often among the biggest employers in their market. As such, while having a strong local-market position has historically benefited incumbents, the double-edged sword of local strength is that it frequently makes implementing much-needed changes slow, arduous, and politically charged. Over the past decade, incumbents have also invested hundreds of millions—even billions—of dollars in areas like EHR systems, proprietary IT platforms, and new buildings. Choices about scaling back on some of these investments will be hard to make, and rethinking assumptions will be challenging.

It’s All About the Consumer

Tackling tomorrow’s adversity will demand new business models. For example, payer and provider organizations can consider cross-sector partnerships to pool their risk. And because a significant part of the shift is to value-based payments, companies can experiment with models such as population-based pricing—in which a provider receives a set amount of money and accepts responsibility for a specific group of patients over a fixed time frame—charging for new treatments only when they are successful.

Payers, providers, and health systems must also steep themselves in data and focus on consumer relationships. This means making sufficiently high levels of investment in digital and analytics capabilities and potentially transforming the cost base to allow them to remain profitable enough at government reimbursement rates.

Digital providers from online retailers to ride-hailing apps have led customers to expect on-demand, instant, customized services—and health care will be no different.

Investments need to reflect the fact that the consumer landscape is shifting. Digital providers from online retailers to ride-hailing apps have led customers to expect on-demand, instant, customized services. And since this is an area open to attack from companies outside the sector, the development of consumer relationships should be given a razor-sharp focus. In a world where cross-year treatments are becoming more common, having “stickier” customers also makes the economics more favorable.

Payers, providers, and health services that fail to foster and manage relationships with their customers will lose them to the high-tech newcomers. But those that can preserve and deepen these relationships will be able to fend off competition from the disruptors and build a future-proofed business that can withstand adversity, no matter where it comes from.