Understanding economic trends in the broadest terms—which industries are expanding, which are on the downswing—can be as straightforward as keeping up with the business headlines. But it’s not quite as easy to get a similar grasp of the job market: not merely which jobs are growing and which are disappearing, but which skills are increasingly in demand—and which are becoming obsolete.

The ability to answer these questions and discern supply and demand trends has major implications. For companies, such insights can improve accuracy in strategic workforce planning by identifying future workforce needs sooner. Companies can adapt their recruitment practices and target their talent development investments more appropriately, even proactively. For governments, insights about the supply of and demand for jobs and skills can inform public policy. These insights are crucial, for example, in reforming education and training programs to better serve the public, businesses, and economies. For individuals, they can guide pivotal decisions about education and careers.

As the pace of technological change accelerates, so does the technology-driven evolution of jobs and skills. Fortunately, technology also offers ways to enhance our understanding of that evolution. With online postings now the primary means for advertising jobs, we have a rich trove of digital data that provides an unprecedented opportunity to understand how the world of work is changing.

In this report, we examine job market trends as reflected in millions of online job postings in the US—collected by Burning Glass Technologies, a leading provider of real-time labor market information—over the three-year period from 2015 through 2018. Although the data covers the US market only, the size and diversity of the US population and economy are a reasonable proxy for global trends. By analyzing the number and growth rate of these listings year over year, we were able to get a picture of the trends in job postings across broad sectors and within specific job areas.

A look at the skills that these jobs require provides a more detailed view of changes in the nature of work. We therefore looked at the skills listed in job postings, classifying them in the same way that we classified jobs.

A vibrant economy and, by extension, a healthy society depend on having an adequate supply of qualified workers to meet current and future demand. Both the economy and society depend on ensuring that individuals are prepared for the future and remain employable. But people change more slowly than technology. As technology affects jobs and the skills required to perform those jobs, we must all adapt.

Many skills can be learned relatively quickly, so companies and individuals who are aware of the latest trends will be at an advantage. In the longer term, the insights now available through big data and analytics tools can help employers and governments more effectively preempt or mitigate demand and supply gaps—and help employees prepare for the future. In a fast-changing world, the sooner we can identify change, the more we can adapt successfully.

Jobs in Demand and Growth in That Demand

Differences in the demand for and supply of particular jobs give us a window into workplace trends and, more broadly, the changing nature of work. To understand how these differences have evolved in recent years, we analyzed more than 95 million online job postings from January 2015 through December 2018 based on data from Burning Glass Technologies. (See “Our Methodology.”) Although the data we studied covers the US job market only, our analysis has global relevance, given the size of the US economy and the similarity of key trends affecting employers worldwide. While online job ads do not represent the totality of job openings, they capture a sizable enough percentage—85%—that the sheer number, breadth, and timeframe of our data set provide a reliable mirror of national job market trends.

Our Methodology

Our Methodology

Each year, Burning Glass Technologies scans millions of job postings in the US and analyzes them using artificial intelligence technologies. Drawing on data sourced from more than 95 million online job postings between 2015 and 2018, we examined current job demand (as represented by the number of online job postings in 2018) as well as the evolution of that demand (as represented by the average of annual percentage changes in the number of postings over the three-year period).

The number of postings for a job can increase because demand is growing or because the supply of qualified workers is shrinking (for example, because baby boomers are retiring). Moreover, want ads for certain traditional jobs, such as barbers, have only started to appear online in recent years. To be clear—and in order to avoid suggesting a one-to-one relationship—we refer to our trend data simply by the numbers: the number of job postings (as a proxy for current demand) and the growth in the number of postings (as a proxy for the evolution of demand). Altogether, we cover 750 occupations derived from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) taxonomy. (O*NET, a database produced under the auspices of the US Department of Labor/Employment and Training Administration, contains hundreds of standardized and occupation-specific descriptions of some 1,000 occupations.)

The 15% of publicly listed job postings in the US that are not listed online are typically for jobs at local businesses that generally require a relatively low skill level, such as pipefitters and steamfitters or automotive specialty technicians. Nevertheless, we took precautions to ensure that our data reflected the true change in market demand and supply, without distortion from job ads that might have migrated from offline to online sources during the period. For each job, we calculated the ratio of online postings to overall employment (using data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics) over the three-year period. Any ratios that showed very high growth (and thus a possible jump in the share of online postings) were flagged as potential false signals for real growth. We analyzed every such ratio on a case-by-case basis to exclude any suspicious data points.

The Five Job Categories

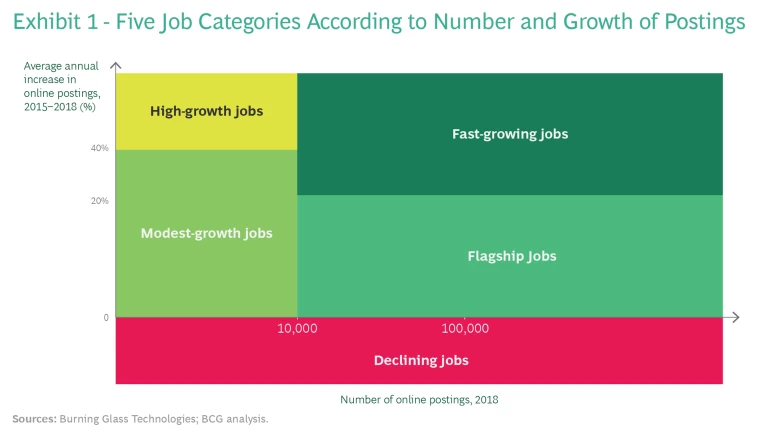

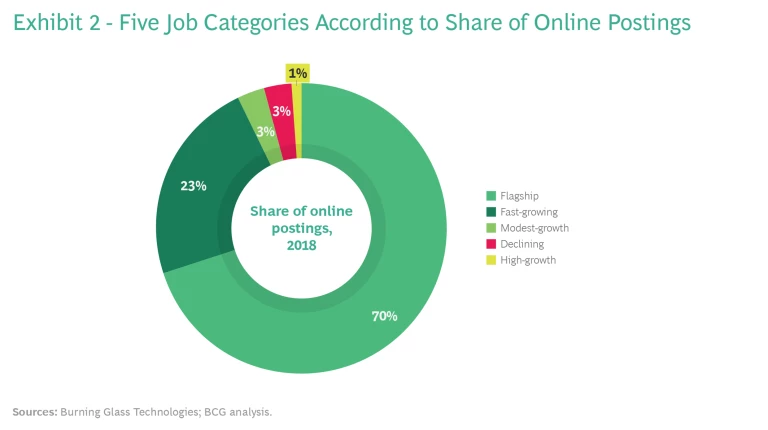

We grouped the jobs in our study into five categories along two dimensions: the number of job postings in 2018 and the growth in the number of postings, as reflected in the average annual change over the period January 2015 through December 2018. (See Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2.)

- Flagship jobs are those in high demand (10,000 to 1 million postings) and still growing (up to a 20% increase in postings yearly).

- Fast-growing jobs also experience high demand but are growing even faster (more than 20% yearly).

- High-growth jobs are those that have fewer than 10,000 annual postings but are growing at an extremely high rate (more than 40%).

- Modest-growth jobs show the lowest demand. Because their impact is limited, we do not analyze them in detail in this report.

- Declining jobs are those for which demand is shrinking.

These jobs span a wide range of sectors and functions, which we organized within seven broad groups based on the US Department of Labor’s O*NET families:

- Business

- Construction and transportation

- Digital

- Health care

- Science, engineering, and manufacturing

- Social services, personal services, and education

- Other

Business jobs, for example, include such traditional functions as general management, sales, customer service, human resources, and administration. Digital jobs include software application development, user support, systems analysis, and IT security.

In four out of our five job categories, growth in the number of postings is increasing. But the fifth category, in which the number of postings is shrinking, is also important to follow. On a macro level, the dwindling number of these jobs provides yet another indicator of an evolving economy; on a micro level, it serves as a warning signal for the businesses in which such jobs dominate and for the individuals who hold them.

Flagship Jobs: Moderate Growth in the Largest Jobs Category

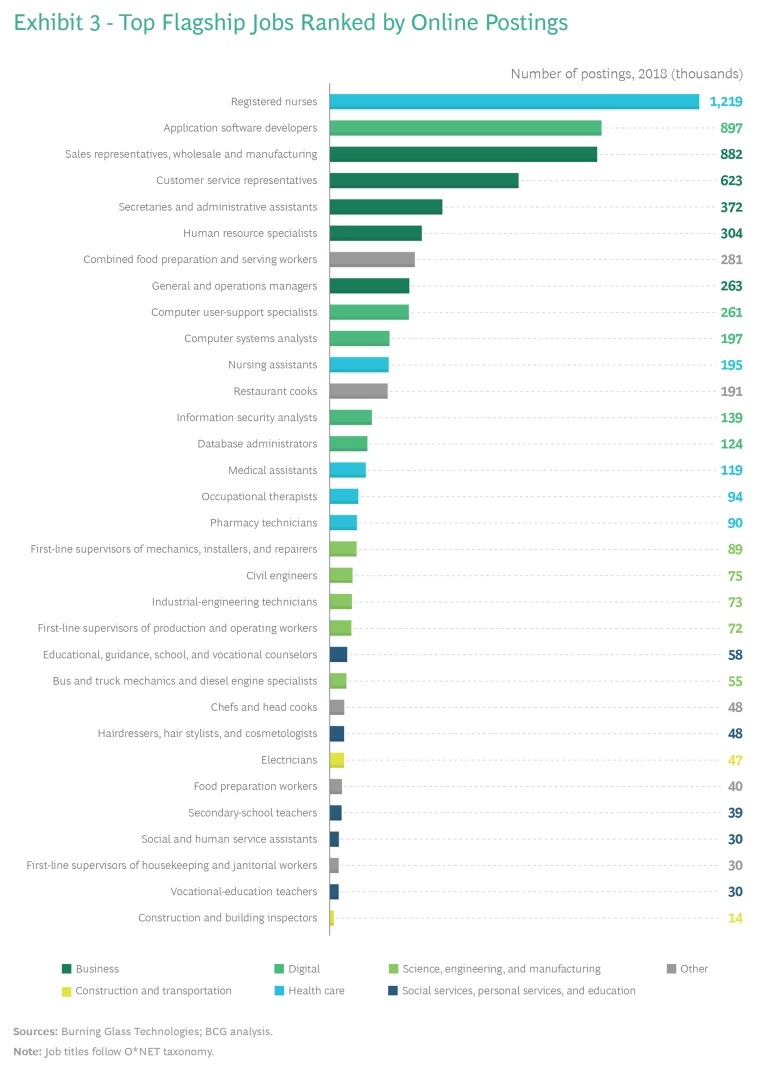

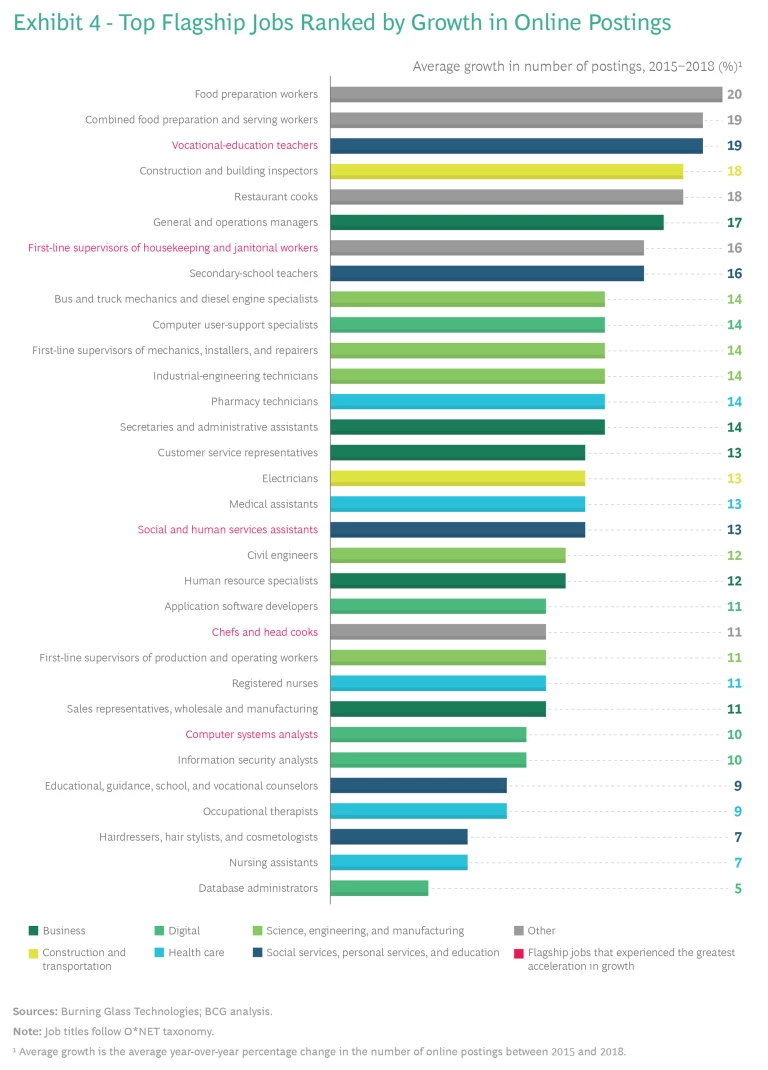

Flagship jobs are those with postings from 10,000 to 1 million per year. Collectively, they represented the bulk of the US economy in 2018. Flagship jobs all experienced moderate growth of less than 20% yearly from 2015 to 2018. (See Exhibit 3 and Exhibit 4.)

In the business job grouping, listings for managers (general and operations), secretaries and administrative assistants, customer service reps, human resources specialists, and sales reps all experienced double-digit growth during this period. In the digital group, jobs in high demand encompassed such areas as computer user support, application software development, IT security, systems analysis, and database administration. Growth in the number of postings in both of these broad categories—business and digital—correspond to the overall growth trend in the recovering economy.

In the science, engineering, and manufacturing group, the top five job areas all experienced posting growth of more than 10% in white-collar occupations (such as civil engineers) as well as in blue-collar jobs (such as technicians and production workers). Both reflect the boom in manufacturing. In construction and transportation, growth in the number of postings for building inspectors and electricians reflected heightened demand fueled by the growth in real estate development. And health care is among the fastest-growing sectors in the US economy thanks to an aging population, as reflected in the growing number of postings for medical assistants, pharmacy technicians, occupational therapists, and nurses.

Not all low-tech jobs are fated to fade away. Consider the social and personal services grouping, in which the dominant growth jobs are teachers, human services assistants, and hairdressers. By definition, such jobs are performed in person and are thus largely unaffected by digitalization. The same goes for the miscellaneous “other” grouping, which includes cooks and other jobs related to food preparation.

Exhibit 4 shows the top five fastest-growing flagship jobs across all of our broad industry groupings. Collectively, the trends within this category indicate the areas of demand growth that are outpacing supply.

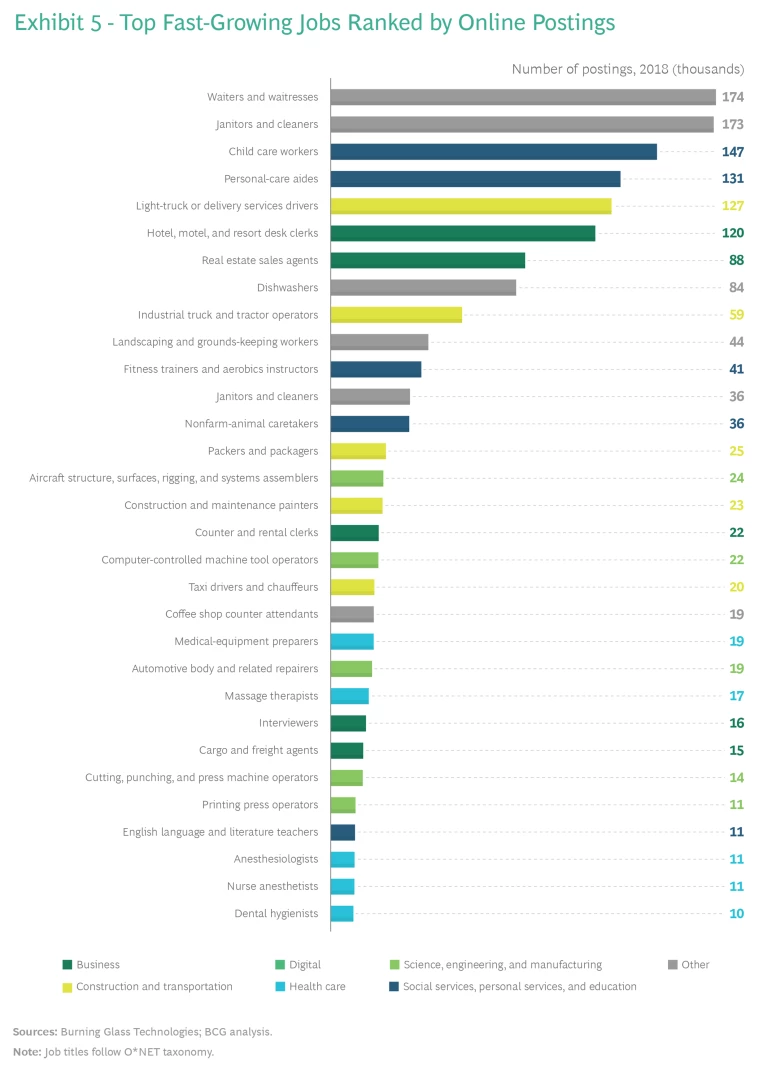

Fast-Growing Jobs: Large in Number and Growing Fast

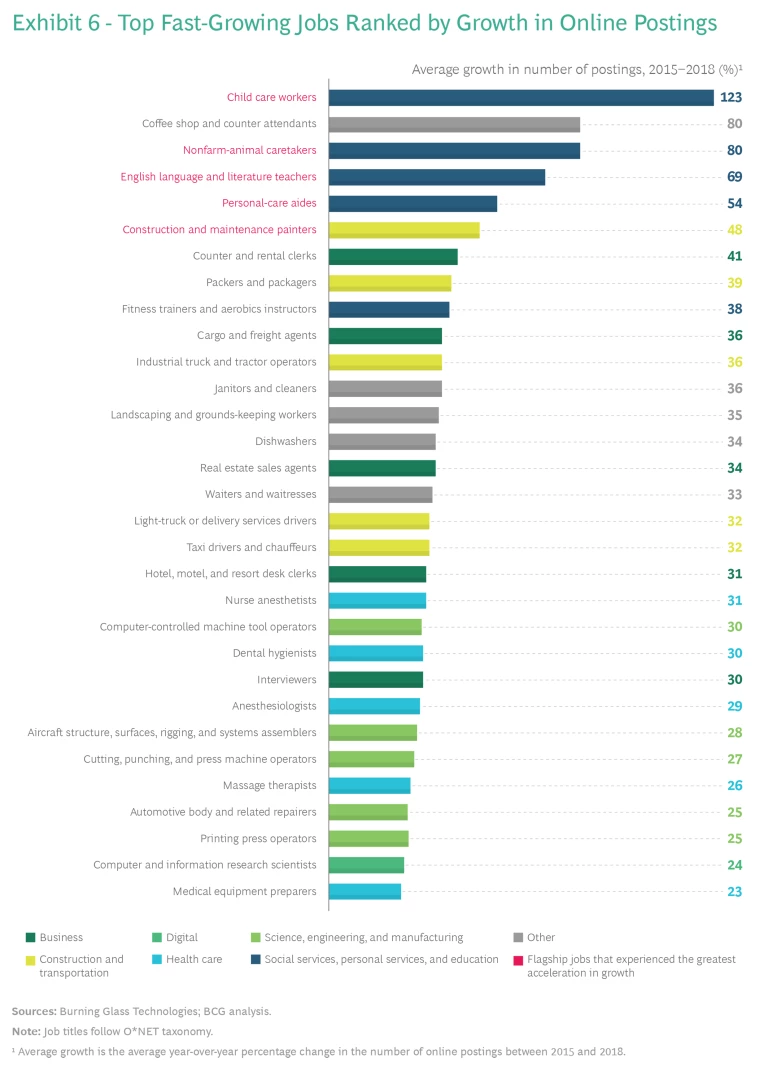

If flagship job patterns reflect current areas of economic growth, fast-growing jobs offer a window into the future economy. Like their flagship counterparts, these jobs are in high demand, but they are growing at an even faster pace: on average, the growth in postings exceeded 20% in each year of the period studied. (See Exhibit 5 and Exhibit 6.)

Among the business jobs in this category are real estate agents, hotel clerks, and interviewers—evidence that new technologies don’t necessarily replace jobs but instead often spur industry growth and job creation. The fields within this grouping all show a strong trend toward automation and disintermediation: consider the use of online videos and websites such as Zillow in real estate, the lodging sites Airbnb and vrbo.com in travel and hospitality, and the use of robo-interviews and the digitalization of many processes in human resources. The aforementioned jobs are in demand despite these technological advances.

In the digital grouping, the only positions showing growth of 20% or more are computer and information research scientists. But this is almost certainly owing to a shortcoming of existing classification systems. Digital jobs have become much more specialized in recent years. Companies no longer seek generalized software developers but rather specify the desired application or language, such as Java/Python developer. O*NET (and other official databases) have not always kept up with such changes.

In the science, engineering, and manufacturing group, growth in such positions as computer-controlled machine tool operators reflects the impact of newer technologies. But there are many traditional manufacturing jobs whose growth is accelerating rapidly. For example, in aircraft manufacturing we are seeing growth of 20% or more in such jobs as structure, surface, rigging, and system assemblers as well as cutting, punching, and press machine operators.

In the construction and transportation group, painters and packagers, industrial truck and tractor operators, light-truck and delivery drivers, and taxi drivers and chauffeurs account for the leading jobs. Growth in the job of truck driver is interesting given predictions that truck driving could become extinct as autonomous vehicles go mainstream. (See “Fast Lane or Off-Ramp? The Paradox of Truck Driver Jobs.”)

Fast Lane or Off-Ramp? The Paradox of Truck Driver Jobs

Fast Lane or Off-Ramp? The Paradox of Truck Driver Jobs

Intensifying demand for truck drivers and increasing growth in the number of job postings for truckers are among the most noteworthy job trends of the past few years. According to our data, job postings for light-truck and tractor operators have grown 32%; postings for drivers of heavy trucks and tractor-trailers grew almost as rapidly, at 29%. In 2018, the shortage of truck drivers hit a record high: an estimated 300,000 positions.*

While the growth rate of postings is accelerating, some experts are proclaiming the end of the era of human-driven trucks. Autonomous vehicles, predicted by many to eventually take over the highways, are considered especially suitable for long-distance trips, which represent a major proportion of freight traffic. So how do we explain this seeming paradox of breathless job growth alongside predictions of job extinction?

Consider some of the factors at work that are squeezing the supply of truck drivers:

- As most freight in the US is transported by road, the strong economic growth of the past few years has increased the demand for long-distance drivers. Short-haul drivers are sought after for the same reason.

- The average age of truck drivers today is 55, so looming retirement further threatens their supply. Moreover, the pipeline is constrained by age restrictions. Drivers must be at least 21 years old in order to cross state borders, so new high-school graduates are not eligible.

- The gender gap doesn’t help: 90% of drivers are male. Unless more women enter the field, the potential pool of drivers will remain limited.

- Millennials have changing attitudes and values regarding on-the-job travel. Industry HR professionals point out that many younger people are reluctant to take jobs that require a good deal of travel and time away from home.

- All the hoopla surrounding autonomous vehicles may have dissuaded many from pursuing an occupation that is purportedly about to disappear.

Essentially, we’re witnessing two opposing trends: in the near to intermediate term, there will be a shortage of qualified truck drivers. But in the long run, self-driving trucks could render drivers obsolete. Companies therefore need to act on several levels to attract workers. In addition to raising wages, they can seek workers from more diverse groups, offer more flexible work arrangements to make the job more attractive, and perhaps even develop next-generation job options should autonomous vehicles become a reality. As we outlined in our joint study with the World Economic Forum, there are many ways that truck drivers can successfully transition into other jobs, all of which require a certain investment of time and money.† But both the company and the individual must approach this in a strategic and forward-looking manner.

* “Why the Trucking Shorting Is Costing You,” Bloomberg News, updated October 5, 2018.

† BCG and World Economic Forum, Towards a Reskilling Revolution: Industry-Led Action for the Future of Work, 2019.

In health care, fast-growing jobs span virtually every major area, from professional specialists (such as anesthesiologists) to caretakers (such as nurses and massage therapists) and from medical equipment preparers to dental hygienists. Similarly, in social services, personal services, and education, among the hottest jobs are child care workers, personal-care aides, and animal caretakers. Overall economic growth, an aging population, and longer workdays are contributing to the accelerating growth of these occupations. Finally, in the umbrella category labeled “other,” service jobs such as waiters, janitors and cleaners, and dishwashers predominate.

Exhibit 6 shows fast-growing jobs ranked by growth and highlights those whose growth we see accelerating.

High-Growth Jobs: High-Tech and High-Touch

High-growth jobs are a beacon of longer-term economic trends, driven primarily (although not exclusively) by the impact of new technologies. They also reflect such developments as the significant increase in air travel and the rising demand for personal services. In 2018, there were typically a relatively small number of online postings (fewer than 10,000) for high-growth jobs, but the average annual growth in such postings from 2015 through 2018 was more than 40%.

Of the high-growth jobs included in the O*NET database, some of those experiencing the greatest growth are airline pilots and flight engineers, automotive glass installers and repairers, and nanosystems engineers. Other jobs in this category are so new that they have not yet been codified in the O*NET taxonomy. So for a more accurate assessment, we looked beyond O*NET’s classification to identify jobs that are growing rapidly but are not yet commonplace.

For example, the number of postings for new digital jobs involving cloud-based services has been growing at a significant rate. The number of online job listings for senior cloud engineers and for Microsoft Azure developers grew, on average, more than 70% each year from 2015 through 2018.

Beyond the expected growth in jobs involving digital expertise and skills, we have also observed a dramatic increase in postings for occupations related to human capital, in particular, talent sourcing and development. The number of postings for onboarding specialists and talent coordinators rose more than 50% on average during the sample period.

Declining Jobs: Whether Fast or Slow, Disappearance Is Certain

Finally, there are the jobs for which demand is steadily decreasing, primarily because they are being replaced by automation or otherwise becoming obsolete through technology. Declining jobs include telemarketers, office machine operators, loan interviewers, computer operators (being replaced by a number of more specific digital and IT jobs), tellers, office workers, and administrative-support workers. These jobs averaged declines in demand of between 2% and 12% during the period 2015 through 2018. Their fate is clear; the only question is how long it will take for them to disappear altogether.

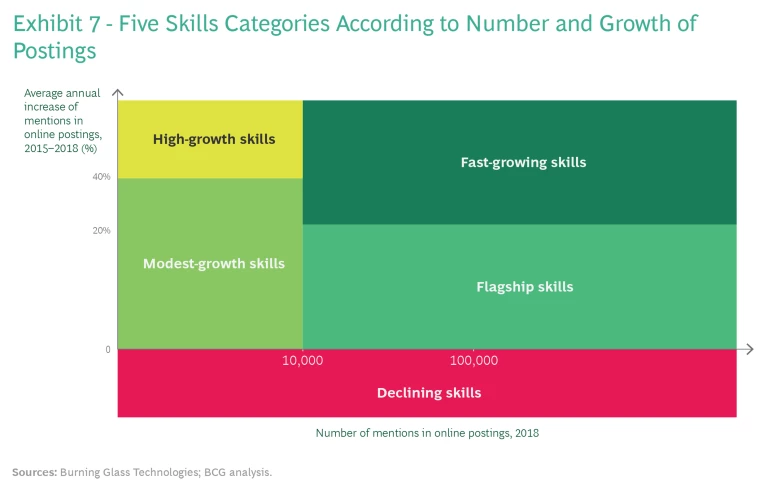

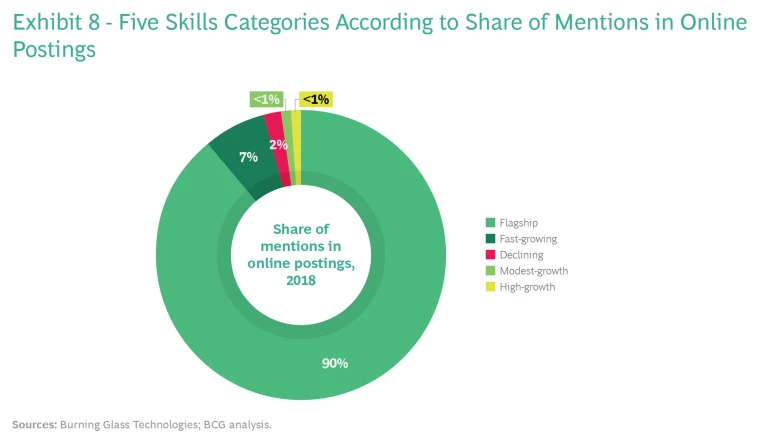

Skills in Demand and Growth in That Demand

The same technological, business, and demographic trends that shape the supply of and demand for jobs likewise affect the market for skills. In fact, analyzing trends in the demand for skills gives us a preview of future job trends, as new skills often arise even before a new technology or trend has produced a corresponding new job title. To be consistent, and because we relied on the identical set of job-posting data, we classified skills according to the same categories used in our analysis of occupations: flagship, fast-growing, high-growth, modest-growth, and declining. (See “Our Methodology for Skills Analysis.”) These designations are based on the number of times a skill was mentioned in the total job listings and the annual rate of growth in that number. (See Exhibit 7 and Exhibit 8.)

Our Methodology for Skills Analysis

Our Methodology for Skills Analysis

To understand skill trends, we analyzed the same data that we used for our occupational trend analysis: more than 95 million online job postings from 2015 through 2018, provided by Burning Glass. We studied the current level of demand, represented by the number of 2018 online job postings in which the given skills were mentioned. We also examined the evolving demand for skills, as represented by the average annual change in the number of job postings in which the skills were mentioned over the three-year period.

Burning Glass’s database tracks more than 17,000 individual skills, grouped into some 650 skill clusters. Skill clusters can be groups of individual skills that are variations of the same basic skill (for example, programming languages); skills that are similar in function (such as meeting planning and making travel arrangements); or skills for which employees can be trained together (for example, proficiency in kaizen and Lean Six Sigma). For the purposes of this report, it made more sense to analyze skill clusters rather than individual skills.

Flagship Skills: In Wide Demand

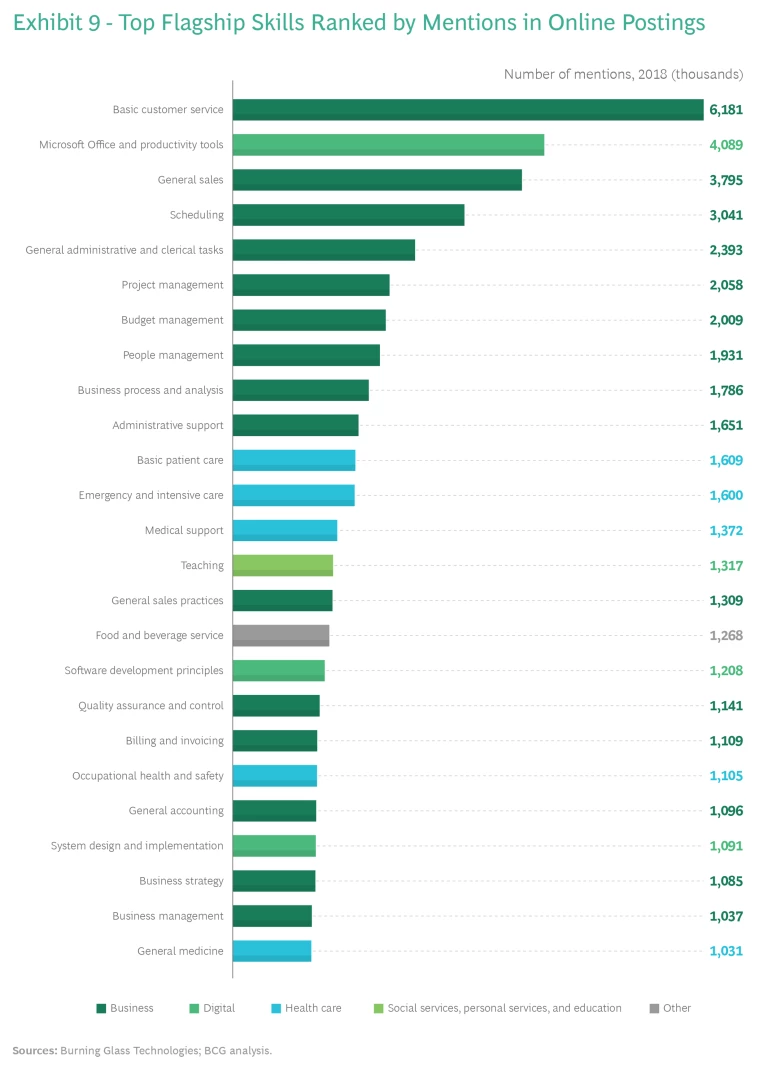

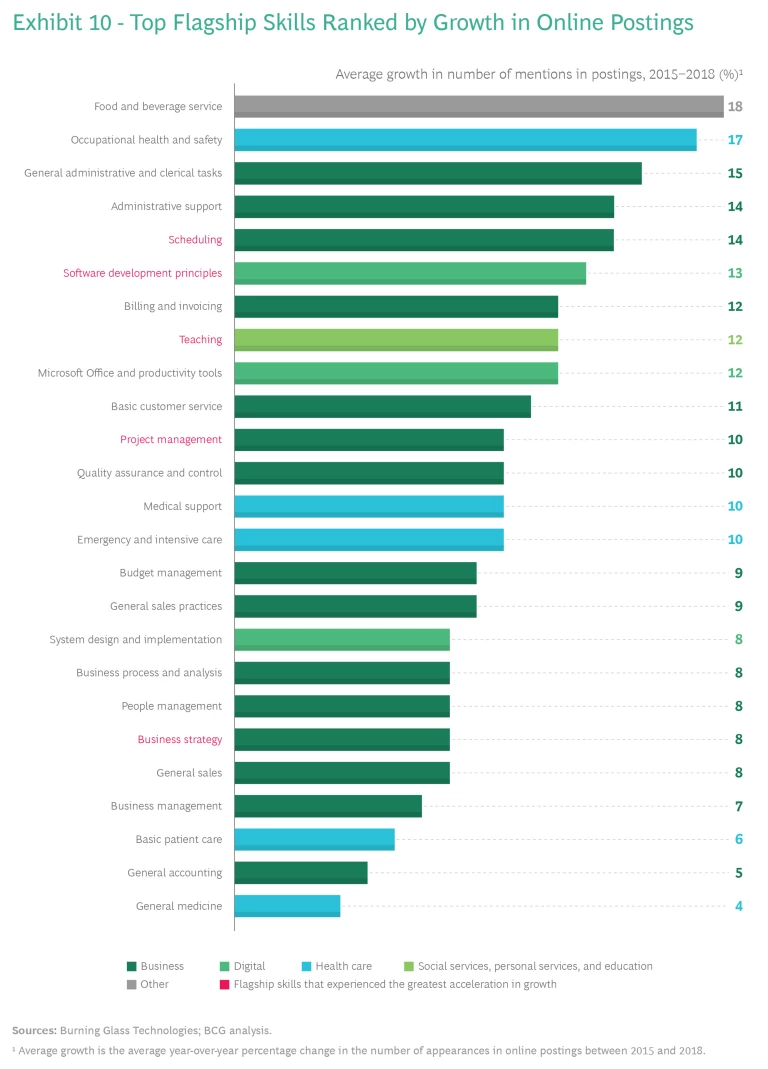

As one would expect, demand for most of the skills in the flagship category is driven by the demand for jobs in the broad sector and function groupings (based on the O*NET taxonomy) throughout the economy. Like flagship jobs, flagship skills show significant demand (more than 10,000 appearances each in 2018 online job postings). These skills are also experiencing growing demand, with up to 20% average annual growth from 2015 through 2018 in their number of mentions in online job postings. (See Exhibit 9 and Exhibit 10.)

Almost 50% of the most sought after flagship skills fall under the general business rubric. They include basic skills, such as handling general administrative and clerical tasks, scheduling, and billing and invoicing, along with those requiring more experience or training, such as general sales. More specialized skills in the category include business strategy, budget management, people management, quality assurance, and project management.

In the digital field, flagship skills are tied more to traditional computer skills, such as fluency in Microsoft Office, or to an understanding of software development principles.

In health care, skills related to general medicine and basic patient care are in great demand, as are more specialized skills such as emergency and intensive care and occupational health. These trends conform to the overall trend in health care, where both general and specialized jobs are growing robustly.

The remaining groupings show a large number of postings for skills associated with jobs that are largely unaffected by digitalization, such as teaching and food service.

As shown in Exhibit 10, the flagship skills across all of our broad industry groupings whose listings showed the largest increase in growth last year were teaching, project management, software development principles, scheduling, and business strategy.

Fast-Growing Skills: Digital and Personal Services Dominate

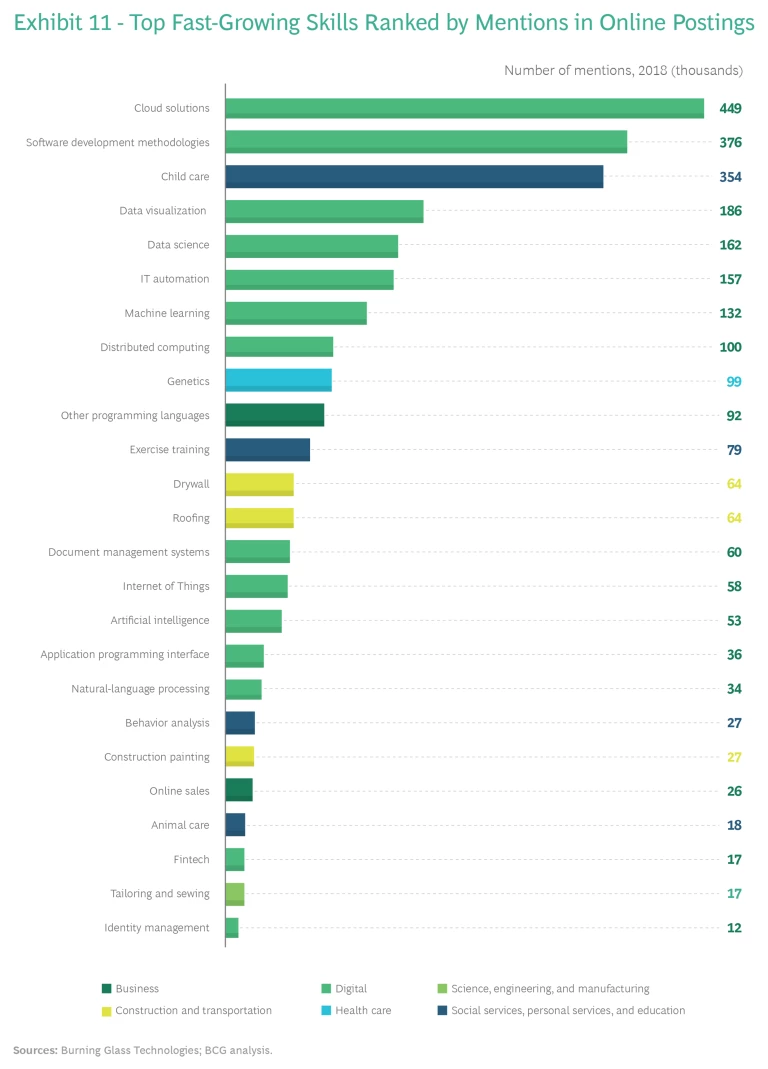

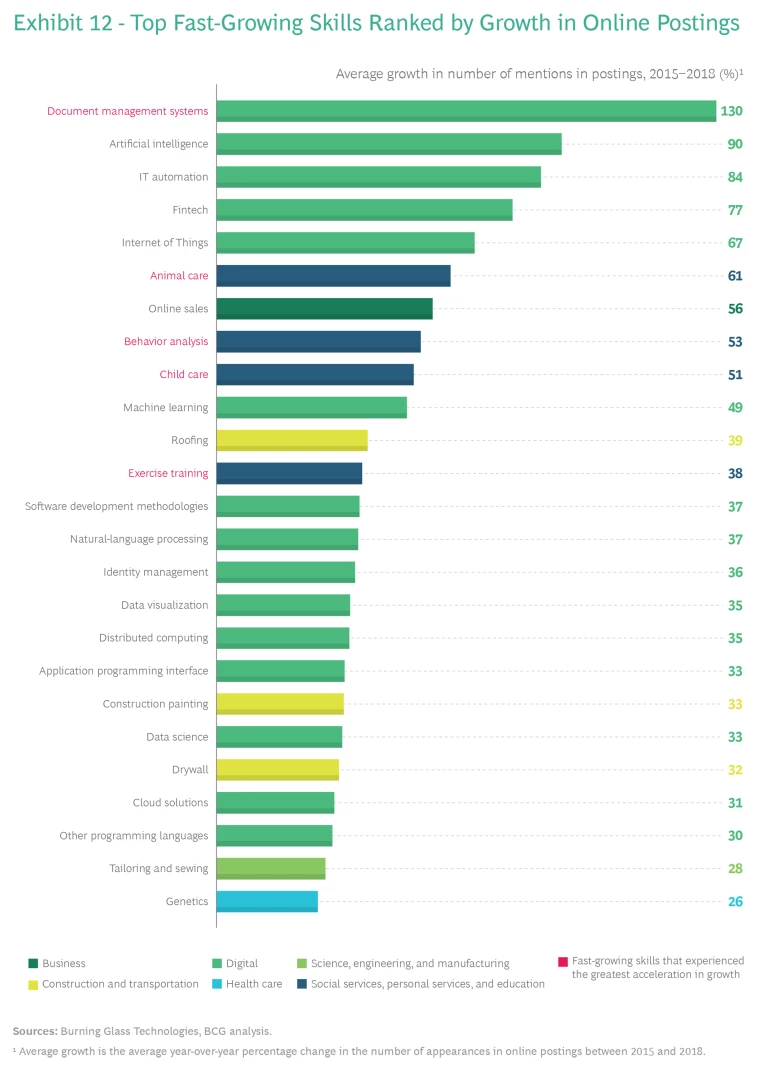

Digital skills make up around 70% of all fast-growing skills: those that saw more than 10,000 mentions each in 2018 online job postings and experienced, on average, more than 20% year-over-year growth in the number of mentions. (See Exhibit 11 and Exhibit 12.) The demand for expertise in fields like artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, cloud solutions, machine learning, and fintech shows the extent to which new technologies are being adopted across industries. At the same time, demand for more “traditional” digital skills is high and continues to grow rapidly; these include handling document management systems, IT automation, and application programming interface. In the business grouping, the only fast-growing skill is online sales—again, a skill set driven by digitalization.

The top five fast-growing skills with the fastest-growing demand from 2017 through 2018 were a motley mix: document management systems, animal care, behavior analysis, child care, and exercise training. Interestingly, the grouping with the largest number of fast-growing skills after digital was social services, personal services, and education. Child care, animal care, exercise training, and behavior analysis skills are all related to the growing pursuit of general well-being and leisure. As with the jobs in this group, high growth and burgeoning demand for these skills are unimpeded by digitalization.

Construction and transportation is another group that is well represented in the fast-growing category, with skills like roofing, drywall building, and construction painting reflecting the enormous demand for housing in the US.

Health care registered only one skill in the fast-growing skills category (genetics), as did science, engineering, and manufacturing (with tailoring and sewing).

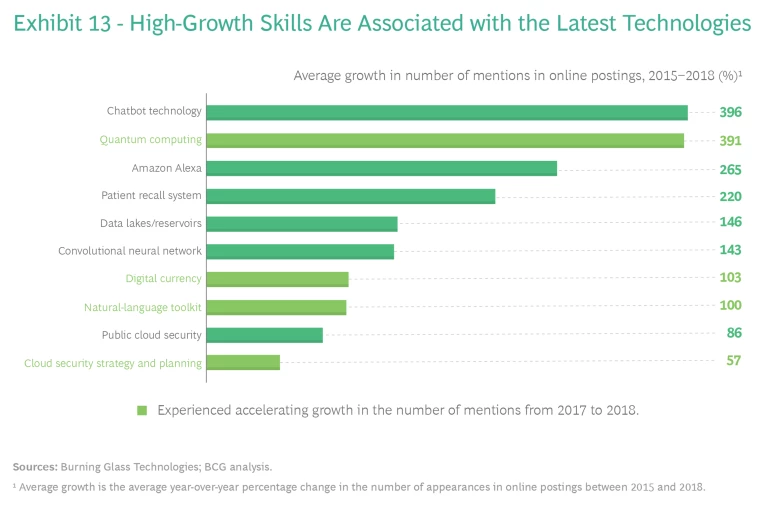

High-Growth Skills: Centered in Technology-Specific Niches

The high-growth skills category offers a view of our evolving digital future. As Exhibit 13 shows, many of these skills are linked to the latest technologies, which are at the beginning of their life cycle. They are in relatively low demand, with fewer than 10,000 individual mentions in 2018 job postings. But demand is growing by leaps and bounds, averaging more than 40% year-over-year increases in mentions in online postings during the period 2015 through 2018.

High-growth skills include those in chatbot technology, Amazon Alexa (the voice-control digital assistant), data lakes, and cloud security. The fastest-growing high-growth skills for 2017 to 2018 included quantum computing, digital currency, natural-language toolkit, and cloud security strategy and planning. While some of the underlying technologies that these skills support may remain niche technologies, others could quickly become mainstream. And as they are more widely adopted, the skills associated with them will be the fast-growing skills of the future. (See “High-Growth Skills Are in Demand in an Ever-Widening Range of Jobs.”)

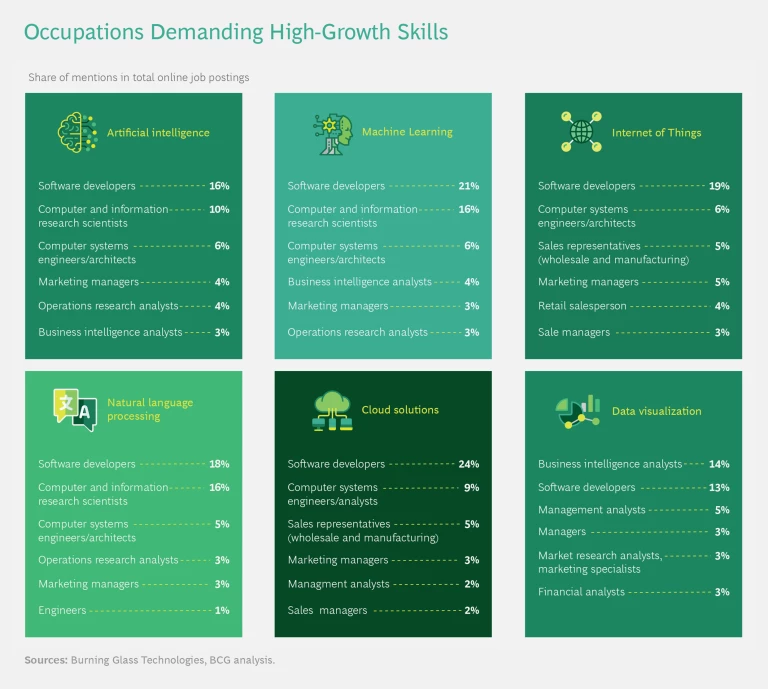

High-Growth Skills Are in Demand in an Ever-Widening Range of Jobs

High-Growth Skills Are in Demand in an Ever-Widening Range of Jobs

As digital technologies pervade core business functions and processes, demand for the more specialized or advanced high-growth skills is beginning to crop up in a wider range of positions. (See the exhibit below.) These skills are increasingly being required in many conventional technology positions, such as software developers and computer systems engineers. Even more interesting, they are emerging in nontechnical job listings as well.

For example, artificial intelligence and machine learning skills are appearing in job ads for marketing managers and business intelligence analysts, and knowledge of or experience with the Internet of Things is showing up as a requirement for various sales and marketing positions. Similarly, proficiency in natural language processing is a requirement for certain engineering positions. And skills in cloud solutions are being called for in various marketing, analyst, and sales positions, as are data visualization skills. We believe this is only the beginning of an important trend that will reshape the skill requirements for many traditional job profiles in the future.

Declining Skills

As new technologies replace old ones, the demand for older technology skills is, as one would expect, declining. Demand is sagging for skills like PHP web, backup software, servers, enterprise management software, and assembly languages. Reskilling becomes a pressing need for workers whose main skill set consists of such competencies.

How Should We Respond?

What do the trends in the demand for jobs and skills tell us? What do they mean for companies, governments, and individuals, in the near and longer term?

The Implications for Companies

There are a number of ways in which companies can address the significant shifts in the types of talent and skills needed for the future, but the process starts with strategic workforce planning. In the context of workforce planning, “strategic” means looking beyond the traditional yearly horizon for staffing plans and developing a longer-term model. At its best, strategic workforce planning comprises not only the roles but also the skills critical for achieving an organization’s business objectives.

We use the word strategic for another reason. Identifying the supply of and demand for the roles and skills most important to a company—and understanding what any gaps in them can mean—should be embedded in the broader strategic business planning process. In other words, no company can have a bona fide strategic business plan without also having a corresponding workforce plan. The workforce plan serves, in effect, as the business case for human capital needs; it is the trigger for buying, building, and borrowing the requisite capabilities. In order for it to be effective, there must be tight cooperation between operations, human resources and finance (and sometimes procurement), because the decision rights and responsibilities for planning and execution typically span these areas.

Recruitment (Buying the Capabilities). Recruitment may be the most established of HR disciplines, but it is also one of the fastest changing. Companies are already modifying their employer value proposition to conform to the changing needs of the contemporary workforce and, in some cases, to compete more effectively for digital talent. Increasingly, companies are also tailoring their value proposition by specific employee segment or market to appeal to the differing priorities of each. Beyond the traditional avenues, companies have at their disposal other new means of talent acquisition, including acqui-hiring, or acquiring companies expressly for their people rather than for their products or services. Finally, new selection methodologies and tools (such as psychometrics and gamification), along with new self-service tools that simplify and streamline dealings between HR and the rest of the business, offer ways for companies to be more proactive in their recruitment practices than ever before.

Development (Building the Capabilities). No company can count on recruitment alone to meet its future workforce needs. The bulk of any company’s workforce remains unchanged from year to year, so companies need to develop their employees on an ongoing basis. Regardless of a company’s ability to attract top talent, it needs to invest substantially in training and upskilling. For example, the trends we found in fast-growing skills indicate that companies need to ramp up their investment in digital-skills building to meet future workforce needs.

Responding nimbly to changing skill requirements is a must in order for companies to remain vibrant. The adage “He gives twice who gives quickly” should guide their approach. New learning methods and tools, such as personalized learning journeys, gamification, and massive open online courses, are fueling an upskilling revolution. The longstanding learning model (70% experience-based, 20% relationship-based, 10% formal training) remains relevant. However, all too often companies focus on the 10% formal training and leave the remaining 90% to employees or their managers. True experience-based learning entails supporting the day-to-day work with learning rhythms and routines (such as projects, stretch roles, and daily huddles). It is only possible if companies are open to flexible career pathways, including welcoming horizontal moves more than they traditionally have. And true relationship-based learning uses expert and community learning group networks (such as peer groups, expert coaches, and online learning forums) to stimulate reflection and reinforcement.

Contingent Labor (Borrowing the Capabilities). Contingent labor can become an integral part of an organization’s workforce. For example, the use of freelancers has become easier, more reliable, and more widespread (thanks largely to digital technologies) and will likely extend to new fields and new positions throughout many industries. Yet in most organizations today, contingent-labor planning isn’t managed centrally; often it is handled by the procurement team, rather than by HR. As a result, it can be difficult to manage as part of a holistic strategy.

The use of contingent labor should be carefully based on strategic workforce planning models and on a deep understanding of the role that various skills play in the organization. It is crucial that organizations adapt their contingent-labor models accordingly—where appropriate, making the process a daily practice. Equally important, organizations need to identify the short list of critical strategic skills that must be kept internal. Outsourcing critical skills creates unnecessary risks, a situation we’ve seen in the IT functions of many companies.

An Alternative for Building the Capabilities. When traditional approaches won’t deliver results quickly enough, there are other options for filling a talent gap, especially for skills needed in bulk. One such approach is build-operate-transfer (BOT). Traditionally used for infrastructure projects developed through public-private partnerships, we have adapted it to help organizations rapidly amass new capabilities. Essentially, the company sets up a new entity tailored to the targeted talent. At first, the entity is operated by an external party; once it is fully functional and able to provide the needed capabilities efficiently, it is transferred back to the company. BOT is particularly useful when the talent in question is culturally different—for example, digital talent—and has needs and expectations that are generally not served by the traditional organization.

The Implications for Governments and Individuals

Reskilling is not merely a necessity for companies; it is also an obligation of governments and public institutions. Many developed economies will face worker shortages. Retraining those whose jobs are becoming obsolete is not only a humanitarian duty; it is a requirement for maintaining economic growth. Governments should both encourage and support employers and employees to engage in large-scale skills-building programs.

In a BCG report produced with the World Economic Forum, we show that reskilling is a realistic option for the majority of workers affected by the shifts in demand described here.

Reskilling, however, is only part of the solution, because it focuses on closing skill gaps in the near and medium term. To ensure that people are equipped not only with the skills required for work in the future but also with the ability to adapt to new ways of learning, policymakers throughout the world should apply their understanding of these gaps to shape elementary, secondary, and higher-level education.