Despite the serious economic pain that the coronavirus pandemic has created for some defense companies—sapping their ability to undertake acquisitions—all is not lost. Defense M&As are still an option. Historically, industry consolidation occurs when US defense spending is on the decline, and, given the trajectory of such spending today, the industry could well be on the cusp of another period of consolidation.

Of course, some formidable challenges await companies that want to tap into the enormous US defense market , as well as for companies that hope to expand an established presence. A wave of consolidation over the past decade has cemented positions, leaving a relatively small number of large players that would be logistically difficult to acquire. Any major deal would surely face careful regulatory scrutiny. With those caveats in mind, companies should plan now for how they could seize opportunities to establish new platforms and beachheads in the US defense market.

The Next Consolidation Wave?

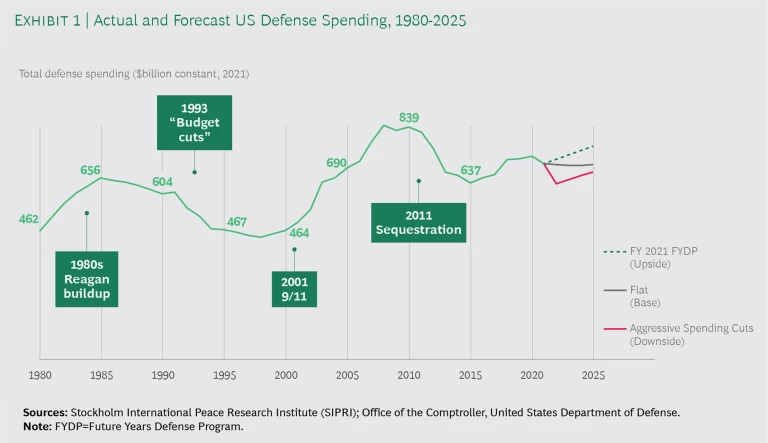

US defense spending tends to go in waves , and we may be about to enter another downturn with aggressive cuts similar to those proposed by the Budget Control Act in 2011. (See Exhibit 1.) While the President’s FY21 defense budget requests an annual 2% increase, our modeling suggests an increase is unlikely, given the size of the stimulus package to counter COVID-19. We forecast a range of scenarios, with the best case being essentially a flat budget, and the worst being a steep decline. If the worst case occurs, it’s likely that new programs will be postponed, R&D cut for all but the most strategic efforts, and current procurements will slip. There could also be pressure to keep existing programs in service longer than planned—which could increase their sustainment costs and modernization requirements.

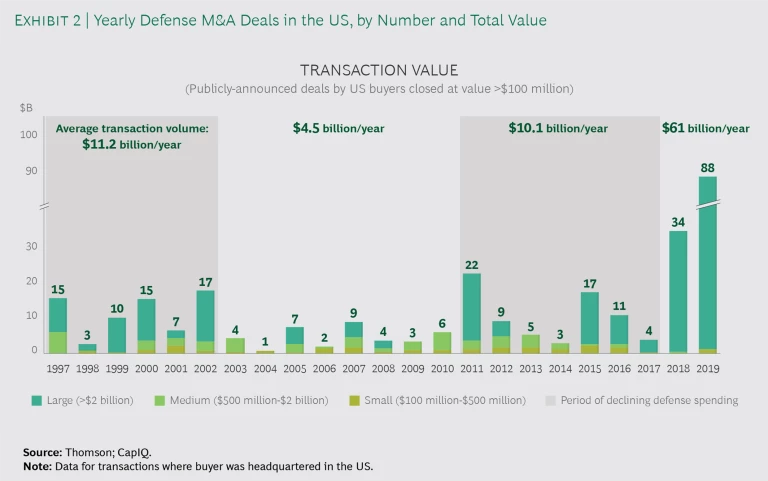

Such downturns have historically been periods of consolidation in the industry, a chance for stronger companies to buy firms in financial distress and either establish a beachhead in the US or expand their presence. (See Exhibit 2.) This presents a near-term opportunity for companies—whether they are foreign firms, domestic commercial aerospace companies, private equity investors, or existing players looking to create new platforms.

For example, BAE Systems took advantage of the downturn in the 1990s to acquire the Sanders electronics business from Lockheed Martin. This put BAE on the path to building a $12 billion business in the US, accounting for 50% of the group’s revenue and making it a major prime contractor. The Sanders acquisition helped BAE establish a Special Security Agreement with the US Department of Defense (DOD), which eventually regarded the company’s US business as a domestic company. Using this as a foundation, BAE went on to acquire United Defense and the Bradley Fighting Vehicle franchise in 2005. The company followed up this acquisition in 2007 with the purchase of Armor Holdings a provider of tactical vehicle and soldier protection equipment. The land vehicle acquisitions proved highly lucrative in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

While it’s true that few companies have the financial resources of a BAE, or the risk appetite for multibillion dollar acquisitions, we still see many opportunities to create custom plays—to assemble what a company wants in a few steps instead of one fell swoop—and at a lower cost than buying a large firm (and with less regulatory scrutiny).

Become a Conduit of Innovation

It’s important to understand that while the prime contractors (aka, “the primes”) are huge, their R&D budgets are relatively constrained—typically just 2% or so of revenue. They tend to focus on winning new programs and developing existing programs but not pure innovation. As a result, their “cash cows” can sometimes get shortchanged on the R&D front. The primes still value these programs, but they must prioritize and often cannot spare the resources to upgrade them.

This creates opportunities for others. A prime might happily divest a seemingly stagnant component business (in order, hypothetically, to focus on system integration) but would be very interested if the new owner of that component business pursued R&D and did the necessary conversion work to help extend the life of the prime’s existing system integration program. In addition, the Pentagon is looking to diversify its sourcing to more creative and flexible vendors who will assume more of the financial risk of system modification and development.

With that mind, we believe that ambitious companies should consider M&A strategies that help them become “conduits of innovation” for the main players. The aspiring company may need to acquire several subunits from existing players to build a cohesive whole, then marry industry knowledge (such as where to find certain expertise or anchor capabilities) together with an analytical understanding of where the leading edge of the industry is trending. This approach requires a coherent vision for what a successful player will look like in three to five years. (See the sidebar, “Six M&A Success Factors.”)

SIX M&A SUCCESS FACTORS

- Identify the desired vertical and entry position in the value chain to build the new platform.

- Develop a thesis about how that platform could generate value based on a vision for where the market will be in five years.

- Understand all the components necessary to build the platform—and what’s missing from the platform today—to seize the opportunity.

- Quantify the thesis to ensure the costs are bearable. Should the company potentially overpay for a piece of the platform, if it knows it will create much more value in the end?

- Ensure there are a range of acquisition candidates to build the platform. If the list of viable targets is too short, the strategy is not viable.

- Move quickly when opportunities arise; most M&A strategies are defeated by a lack of courage, not lack of targets.

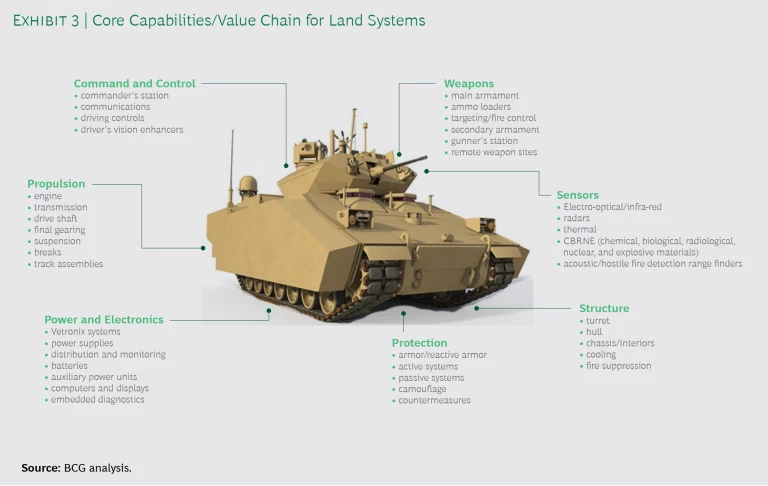

This approach also requires that companies understand the core capabilities for success in each domain. (See Exhibit 3 for the land domain.) For example, while the US Army needs combat vehicles to fight and sustain multiple operations, the vehicle itself is a commodity. The real value is in the payload/sensor package. Combining this package with real-time data analytics could be powerful. Another opportunity lies in the US Special Operations Command’s desire to reduce integration costs for C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), enhance suspension technology, and improve the life cycle of nonstandard commercial vehicles.

Also worth noting is that the DOD is putting a new emphasis on innovation and speed. The DOD requires the Modular Open System Approach, or MOSA, on all major defense acquisition programs so platforms, subsystems, and components can share major system interfaces. As a technical strategy, MOSA is focused on a modular system design utilizing widely supported industry standards to keep up with change and evolution. As a business strategy, MOSA enables nontraditional DOD contractors to participate in major DOD programs.

Think Boring, Then Get Creative

Often the first step in an M&A strategy is finding some mundane corner of the industry, a business that looks stagnant or is even suffering a declining order book. The owner might be easily convinced to jettison such a business—perhaps even enthusiastically—at a reasonable price. The trick at this stage is not to set one’s sights too high, such as building tanks or jet engines. Instead, boring is usually better. Maybe focus on combat propulsion systems and armored structures that seem mature and without obvious growth potential. The goal with the acquisition is not to make a big splash immediately, but to get a foothold in the US defense market, access an established customer base, and create a platform to add capabilities and leverage cost synergies.

Of course buying into a boring, stagnant business is not by itself a great strategy. The next step is to identify and acquire technologies that can improve the newly purchased company’s product. There is, in fact, a lot of potentially useful innovation going on in the commercial sector. But the commercial sector is generally ill prepared to integrate civil technology into the complex defense space. This creates an opportunity for a company serving the defense sector to take untrusted commercial technology and use it in a “trusted” way for the defense sector. For example, technologies and innovations supporting 5G are directly applicable to DOD requirements for radar and electronic warfare. Intellectual property is valuable in all of the defense businesses and is key to future revenue.

Establish a New Platform

It’s not easy to put all these pieces together, but it can be done. For example, after 9/11 the airport security market began to grow significantly. That prompted L-3 Communications, which had an existing unit that developed explosive detection systems for airports, to acquire PerkinElmer’s x-ray business unit for $100 million—a rather “boring” and “mature” part of the market. But with this complementary purchase, L-3 could respond to requests for proposals from ports and airports with a full suite of security products, eventually adding MacDonald Humfrey Automation UK for $280 million, helping to boost revenues to $500 million. L-3, which ultimately became L3Harris Technologies, sold its security detection and automation business to Leidos for $1 billion in 2020.

This strategy worked so well, L3Harris used the same approach in another corner of the aerospace and defense market. It had an established relationship with the DOD providing intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and communications capabilities. To expand that relationship, L3Harris acquired Ocean Server and Open Water Power, positioning itself as a leader in the portable, unmanned undersea market. The Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit recently selected L3Harris’s newest unmanned underwater vehicles (Iver4) for the US Navy to conduct expeditionary and undersea missions.

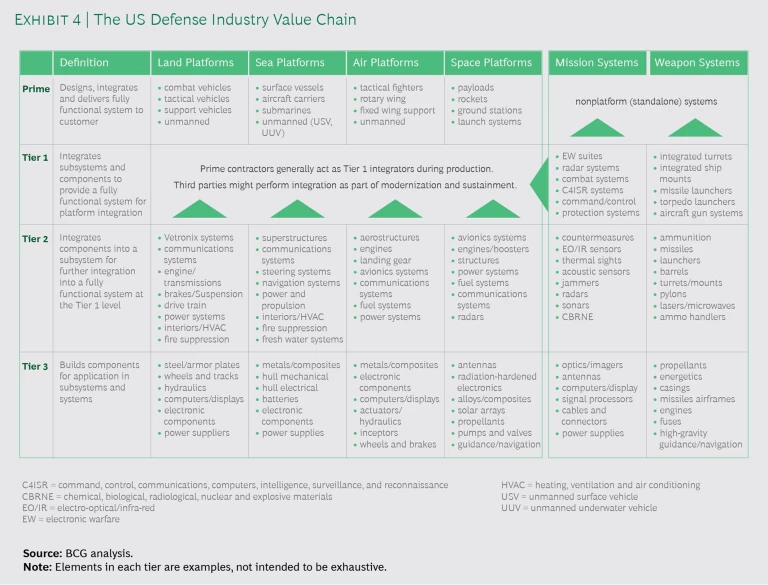

Was L3’s experience unique, or can others emulate the strategy? Based on our work in the industry, we have concluded that it is a repeatable strategy. The first step is to identify the precise area in the value chain and the level of entry. (See Exhibit 4.) Prime or Tier 1 businesses are more desirable, but command higher multiples. Tier 2 and 3 businesses are more accessible, but may be subscale or in less attractive segments.

One possibility is to pursue a “chink in the armor” strategy, targeting a Tier 2 player in a specific segment and then patiently developing a stealthy strategy to expand vertically up the value chain and horizontally into other verticals. A large foreign player could plan in cost synergies over time by harmonizing processes, streamlining management, sharing highly specialized employee skills, and bringing their own proven processes and technologies to the US market.

Recent developments in the US defense industry has placed it on the cusp of the next consolidation wave. Companies looking to make inroads have no time to waste. They need to lay their plans now to capitalize on opportunities. For most companies—those aspiring to enter the market and those looking to expand their presence—a multibillion dollar acquisition is probably out of reach.

Instead, they should consider establishing a new beachhead, finding an entry point, and creating a strategy to move up the value chain. Each company’s exact path to enter or expand in the US defense market will be unique to their circumstances. But a guiding principle should be to become a conduit of innovation.