Traditional management has reached a breaking point. Today’s managers are burning out. Junior employees would rather move into an expert position or work for themselves than become the managers of tomorrow.

If those statements sound overblown, consider these findings from a BCG and Ipsos survey of 5,000 employees, 30% of them managers, in five countries:

- The Now—81% of Western managers think the job is harder than just a few years ago.

- The Future—63% of Western managers do not want to stay in management and 37% believe their management layer will disappear within five years.

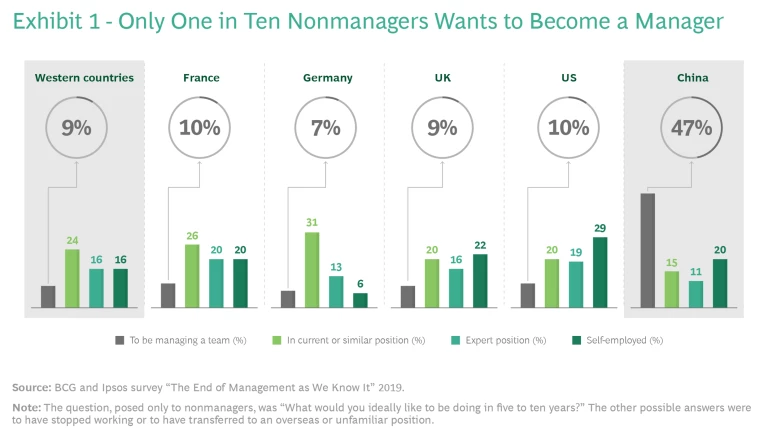

- The Existential—just 9% of Western nonmanagers aspire to become a manager. (See Exhibit 1.)

The middle-management crisis has been around for decades. What’s different now is both a recognition that the management model is in flux and the emergence of a credible replacement.

Agile ways of working, which emerged in the tech startup world and are now taking root in many kinds of large organizations, show strong flashes of potential as the organization model of the future. This approach addresses what employees dislike about their jobs and sets aspirations in line with what employees say they want at work. (See “A Breaking Point” for a summary of survey findings and the appendix for the survey methodology.)

A Breaking Point

A Breaking Point

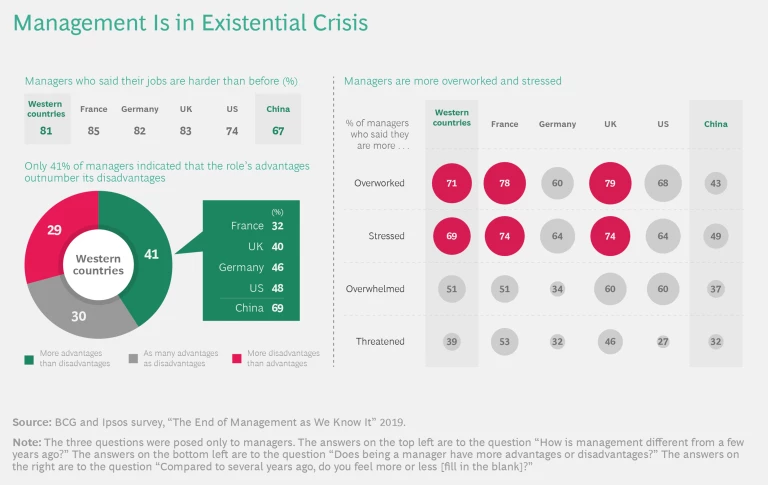

Western managers, especially those in France and the UK, are more stressed and overworked than they were several years ago. They also feel less supported. Chinese managers are more optimistic about today but, as we explore later, pessimistic about tomorrow.

These findings are anywhere from worrisome to existential in proportion. They are certainly not good. Of Western managers, only 41%—32% in France—said that the advantages of being a manager outweigh the disadvantages. (See the exhibit “Management Is in Existential Crisis.”) Only 37% would like to still be a manager in five to ten years.

Managers don’t like being managers, and most nonmanagers do not want to become managers. Nearly one-quarter, or 24%, of Western nonmanagers would rather stay in their current job than become a manager; 28% want to have stopped working within five to ten years.

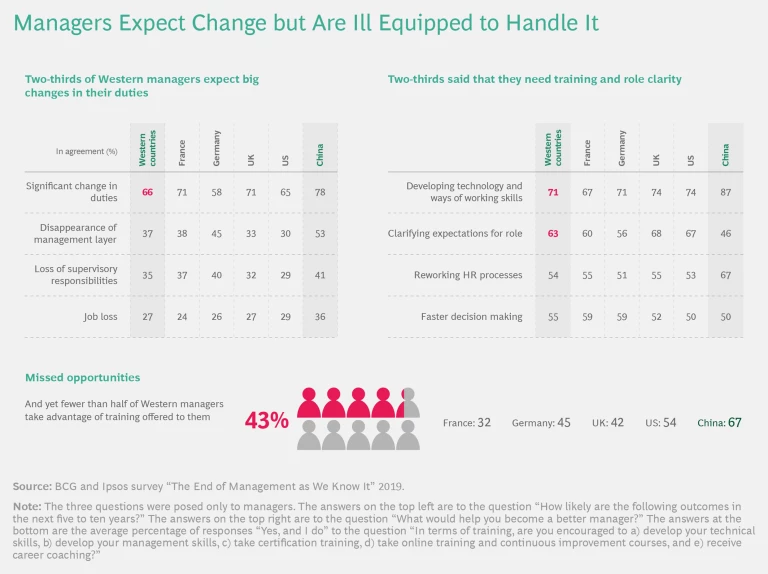

Managers, including those in China, recognize that their discipline, in addition to being harder, is in a state of flux—and not always in a good way. Two-thirds said that technology and other forces will probably fundamentally affect their jobs in the next five years. Over a third—and even more than that in China—indicated that they think their management layer will probably disappear in five years, while a quarter are worried about losing their job. (See the exhibit “Managers Expect Change but Are Ill Equipped to Handle It.”)

At the same time, managers recognize that many of these changes present opportunities, too. In the West, more than twice as many managers view as positive rather than negative the emergence of digital technologies, the entry of Gen-Y and -Z into the workforce, and even the automation of supervisory and monitoring tasks. Chinese managers are even more optimistic about these trends.

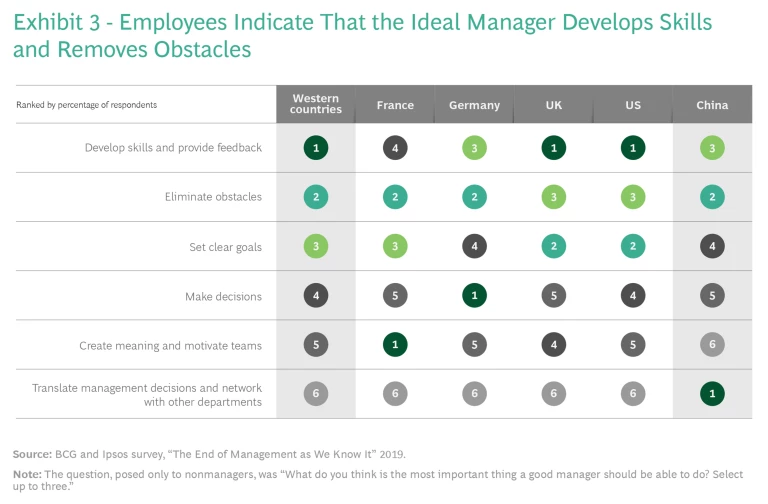

For all the changes that technology and generational change bring about, nonmanagers have fairly traditional views of what they expect from their bosses. The top five attributes that Western nonmanagers value in their bosses are:

- Helping employees develop skills and providing feedback

- Eliminating obstacles

- Setting clear goals

- Making decisions

- Creating meaning and motivating teams

All five views are much closer to basic than new-wave management skills.

Many companies are experimenting with agile, and a few have gone beyond the tipping point and reached scale , which is a whole new challenge. Most are still early in the multiyear work of redesigning management roles, career paths, and the leadership and development agenda . But the early returns are encouraging as a long-term answer to the death of Taylorism and traditional management .

Lost in Translation

The central paradox of managers is that they know what they would like to change about their jobs, but few actively seek to change. They are adrift between the death of one form of management and the birth of another. They are Bill Murray in the Tokyo hotel in the movie Lost in Translation, unable to act. Given the opportunity to reallocate their time, the survey shows, managers would shift less than four hours a week, hardly enough to make a big difference.

Managers said that they want to improve their technical skills and stay up to date on new forms of communication, collaboration, and working. Yet most of them do not take advantage of development programs and on-the-job training that allow them to become more strategic. This is true of both company-sponsored programs and those available through the growing e-learning market. Just one-third of managers, for example, receive career coaching—and remarkably only 17% do so in France.

The Root Causes of Management Misery

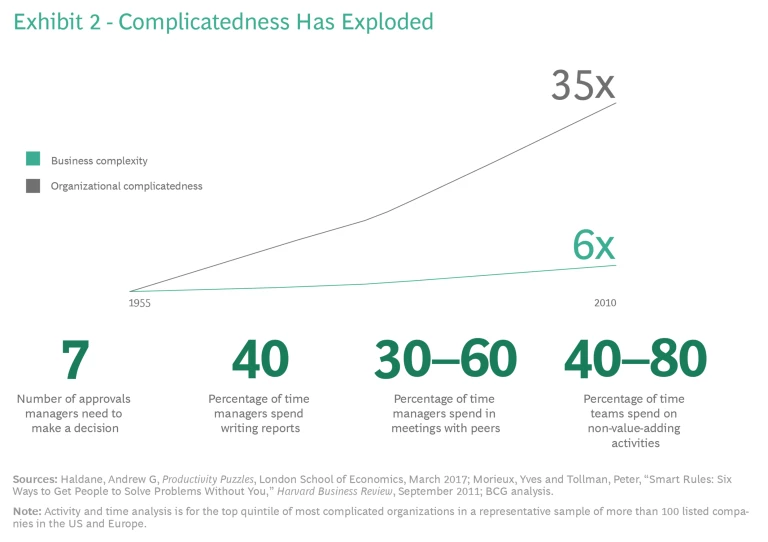

Our colleagues Yves Morieux and Peter Tollman persuasively argue that managers are bearing the brunt of the rising complexity in business that’s been brought on by technological change, globalization, market volatility, and other forces. Employers respond by imposing new rules. The number of structural fixes has grown by a factor of 35 over the past 55 years, nearly six times faster than the business complexity it was meant to address. (See Exhibit 2.) As this “complicatedness” rises, employees spend large chunks of time on aimless activities that keep them from getting the job done—and getting the job done is what a majority of employees want and enjoy most.

Organizations cannot write enough rules or build enough new processes to cover all the possibilities created by uncertainty and change, especially the exponential changes from digital technologies. Managers are literally stuck in the middle of competing priorities. Products need to be affordable but high quality. Manufacturing plants have to be efficient but safe. Effectively dealing with such complexity would require managers to have more room to maneuver in order to make the right tradeoffs. Instead, managers in our survey said that they devote most of their effort to providing updates, preparing reports and presentations, and coordinating across organization boundaries—and less than one-quarter with their teams or clients. They are fighting on the front line of complicatedness rather than problem solving with their teams.

In the meantime, many issues that are escalated up the chain of command cannot be handled by know-it-all senior executives—because they do not know it all. They cannot know it all. They are overloaded. What’s more, they often did not grow up with new technologies and ways of working.

Agile to the Rescue

To thrive today, companies need to access diversity of thought and experience. And to harness this collective intelligence, organizations need to bring together multi-disciplinary teams that are free to pursue different approaches. They need to create dozens or even hundreds of teams, each with a startup mentality.

At the same time, companies need to frame and manage team autonomy so that it is purposeful. In an agile organization, leaders do this by setting a clear vision, objectives, and guardrails for teams. And then they step back and let the teams do their work.

Because these teams are self-directed, they sometimes bump into one another. They have to learn how to avoid overlapping and competing priorities through, for example, dedicated meetings. Leaders play a critical role in providing the right frame for team alignment, pushing decisions down to the right level, and removing obstacles, such as bureaucratic approvals, that stand in their way. Leaders also must show the way forward by embodying agile and new ways of working. Rather than engaging in behaviors that worked in a command-and-control setting, they should be aligning and cooperating with their peers and serving as role models. Coaching is often essential.

Agile is a set of principles that allow teams to flourish in this environment of autonomy and alignment. Ideally, each team possesses all the skills needed to solve a problem or deliver a service. Teams are generally cross-functional and end to end in orientation. They are experimental but rigorous in tracking results, and they are persistent.

Organizations bring these principles to life in different ways. Teams developing a new mobile-app feature have different needs and a different workflow from a bank’s contact center, a pharma R&D operation, or the work benches of engineers developing new hardware in an industrial and highly regulated company.

In most versions of agile, the role of the manager as the boss largely disappears. In its place, two distinct leadership roles emerge: the what and how roles. What should a team be working on, and how should members of cross-functional teams continue to advance their skills and careers? (See “The Agile Leader.”)

The Agile Leader

The Agile Leader

There isn’t just one type of agile leader. There are at least two.

A leader in the what role helps the team decide what to work on and makes sure that the work stays in line with the overall vision of the company. These leaders ensure that teams are working on the right things and support them in their work. In many organizations, they are known as product owners.

A leader in the how role manages the professional development and careers of employees with similar skills. These employees, who generally work on different teams, come together to sharpen professional skills that otherwise might get diluted by their general duties on a cross-functional team. This focus is critical because skills are both more important and more fleeting than ever.

For most managers, the how role is both new and different. It is about managing the careers and professional development of employees with whom they do not have a solid-line reporting relationship. In many cases, it is a part-time role.

Often, teams are also supported by coaches who help them collaborate and perform more effectively. Companies that transition from traditional to agile ways of working may temporarily rely on a lot of coaches to support employees as they learn how best to work in autonomous, multidisciplinary teams. Over time, coaches typically play a smaller role as the company deploys agile at scale.

These supporting roles are more appealing than the coordinating and directing role that current managers find distasteful. In the survey, for example, Western managers flagged implementing decisions they don’t agree with as their number one dissatisfaction. Leaders of agile teams generally do not have this complaint. As part of their framing work for teams, leaders have rich discussions with other leaders and teams about execution of strategy and prioritization. They actively build alignment rather than passing along orders and directives. At the same time, agile enhances the activities that Western employees say they are looking for in their bosses: helping teams make progress and develop skills. (See Exhibit 3.)

Finally, agile provides a potential way around the existential finding that nonmanagers do not want to become managers. Our client work suggests that the new leadership roles in an agile organization are often desirable for younger and new employees because these positions are focused on work, mastery, and coaching, rather than reporting and playing politics.

In their full incarnation, agile organizations offer attractive alternatives to the management ladder. They allow and even encourage employees to move between career track roles more smoothly. Nonmanager positions such as expert are valued and offer the same potential for recognition and reward.

Management, Reinvented

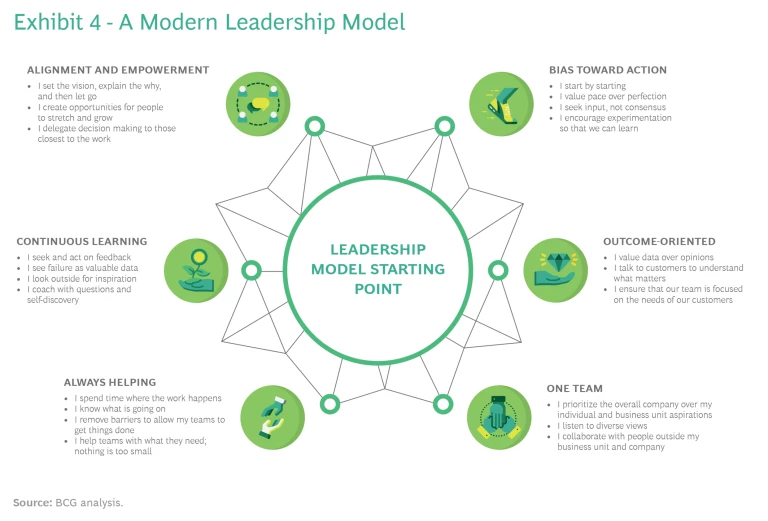

Agile is not a panacea. An agile structure can be put in place relatively swiftly, but successful, large organizations spend years building agile muscles. At scale, agile requires a new organization operating model, beyond just a few tweaks to the leadership and development model. (See Exhibit 4.) And it requires hard work to bring along managers and employees accustomed to a very different way of working.

Employees who start their careers in an agile organization generally take to agile easily. But seasoned veterans need training and time to become comfortable in new roles. (See “A Senior Leader Learns to Be the Moon.”)

A Senior Leader Learns to Be the Moon

A Senior Leader Learns to Be the Moon

A senior bank leader (let’s call him Peter) once spent a good chunk of his time attending steering-committee meetings. He was comfortable making decisions in those meetings even while recognizing he probably did not have the full context or background.

That all changed when the bank adopted agile. Peter, who once told subordinates what to do, was told he now had to ask those same employees how he could help them. The transition was not easy. He had a coach who helped him with this new way of working, and she told him bluntly, “You are not the sun. You are the moon.”

The transition into this new role was not necessarily easy for his subordinates, either. Peter would often have to ask them four or five times if they needed his help before teams took him up on his offer. Eventually, Peter’s new role as a servant-leader took hold, and he began to take satisfaction in even small victories, such as removing weighty and redundant approval processes so that teams could act faster.

Not only did Peter’s role change but so did his KPIs. After meetings, for example, teams would evaluate Peter on such measures as: Was the leadership team well prepared? Were they paying attention? Were the meeting and discussion with the leadership team useful?

On a personal level, a 45-year-old engineer, accustomed to overseeing employees, may have trouble with the transition to spending half the time working on a team and half the time coaching less experienced engineers.

When companies shift to agile, teams are quicker to embrace this new way of working than current managers who may fear the loss of status or power. With strong change management, training, and coaching, this can be temporary. Already ill at ease in their current jobs, most managers come around if they are shown the opportunities and receive training and coaching on agile leadership.

At one company that is rolling out agile globally, managers all invested time in a series of half-day workshops and individual coaching sessions on agile leadership behavior. During the workshops, they focused on team alignment and identified gaps in their own behavior through a peer feedback exercise. This exercise helped persuade them of the need to change. The coaching gave them the tools and confidence to take risks and experiment with new behaviors. For instance, all leaders committed to experimenting with an agile “ceremony” with their team. The act of committing to try something new is a nudge to encourage new behavior. Making such a commitment in front of peers increases the likelihood of following through. And focusing on a recurring behavior such as a ceremony helps convert these nudges into day-to-day habits and make the new behavior stick.

Leadership and development programs can only go so far. HR processes also need to provide the right incentives in order to align performance management with agile values, encourage intrinsic motivation, and rethink talent management, career tracks, and onboarding practices. ING Netherlands, an early adopter of agile outside of tech, has introduced the concept of “craftsmanship,” a commitment to skills, pride, and professional development reminiscent of the guild era.

On their first day of work at ING, employees learn the motto “Stay curious, keep learning, and take ownership.” In other words, own your professional development.

At large organizations that have successfully transitioned to agile, the payoff in business performance is real and sustainable. The work of cross-functional teams often overshadows the role of managers in team success. It’s time to recognize that agile works in part because it releases the latent potential of managers to foster cooperation.

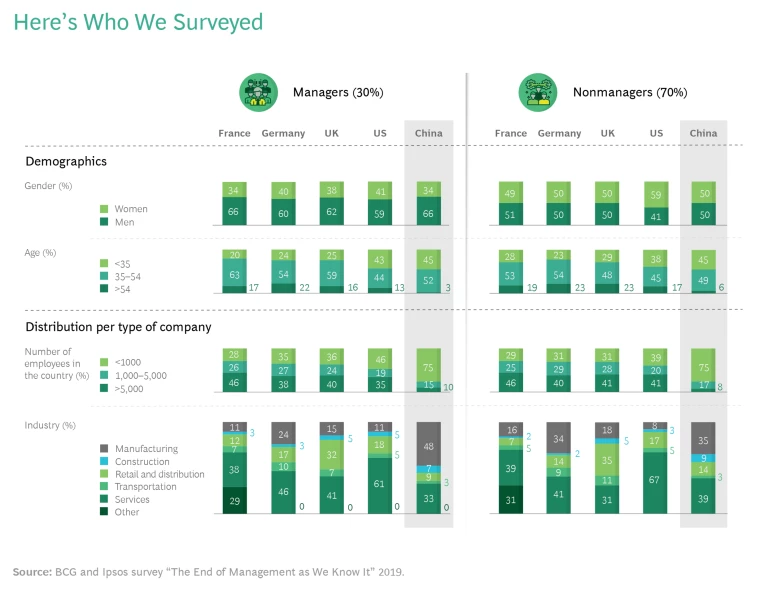

Appendix

Boston Consulting Group and Ipsos, a global market research firm, partnered to survey 5,000 employees, 30% of them managers, in five countries about the state of management and the potential of agile. The survey was conducted online in late June and early July 2019 and complies with ISO 20252, the international standard for conducting market, opinion, and social research.