This article about BCG’s ready-made scenarios was written before the coronavirus pandemic, a moment in history that underscores the importance of resilience. Scenarios such as the ones outlined below stretch thinking beyond forecasts. They prepare organizations for the unpredictable and for whatever lies ahead.

The future is inherently hard to predict, which makes planning for it especially challenging. Strategies don’t last forever, and the best guarantee of sustained success is an open-minded culture prepared for uncertainty. Scenarios have offered a time-tested way to pressure test strategy against a plausible and diverse set of outcomes.

Strategies don’t last forever, and the best guarantee of sustained success is an open-minded culture prepared for uncertainty.

Companies, for example, that explored the risk of supply chain disruption in a scenario exercise are discovering this benefit. So are educational institutions that leaned into virtual and alternative forms of learning.

Many organizations, however, lack the time and resources to do the type of full-blown “made to order” scenario exercise popularized by Shell and others. We’d like to propose a streamlined option.

As a flight simulator prepares a pilot to respond to the unexpected, we’ve developed four ready-made scenarios on the basis of important geopolitical, technological, and socioeconomic uncertainties. Each is plausible but a stretch. These scenarios can help organizations discover strengths and vulnerabilities, create robust strategies, and respond to change.

The Four Scenarios

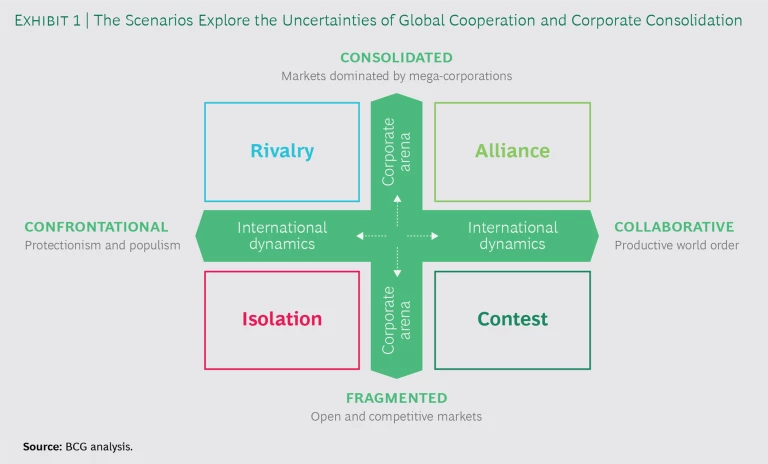

Although the four scenarios are rooted in multiple uncertainties, they are anchored by two questions that reveal themselves in so many of today’s events: Will countries collaborate with one another or take a confrontational and closed stance? Will corporate power fragment or consolidate, especially around digital oligopolies? (See Exhibit 1.)

In answering these two straightforward questions, a variety of possibilities emerge. To broaden the aperture, we enriched these potential outcomes with other uncertainties that are relevant across industries.

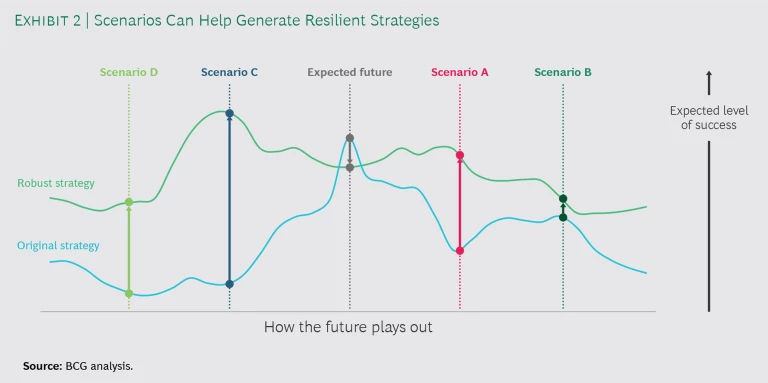

An effective strategy should perform well in a variety of scenarios, not just the most likely, least disruptive, or most familiar. Using scenarios to test alternative strategies may reveal that the initial option puts too much faith in our ability to predict the future while others may be more resilient. (See Exhibit 2.)

To illustrate the practical application of our scenarios, we consider a hypothetical global R&D-focused pharma company based in Europe. A Middle Eastern government is dangling an attractive package of incentives to build a net-zero-carbon manufacturing facility that would supply its three major markets, China, Europe, and the US. Tempted but wary, the company leaned on the scenarios to help inform its decision. It evaluated its situation in the context of our four scenarios: isolation, rivalry, alliance, and contest. (For a fuller picture of the richness of the scenarios, see “Constructing the Scenarios.”)

CONSTRUCTING THE SCENARIOS

CONSTRUCTING THE SCENARIOS

Scenarios should force organizations to think about how they would perform under forces over which they have little control. In our work with clients, we frequently hear about uncertainties. Stepping back, we identified six big ones that keep executives awake at night:

- International Dynamics. Inter-governmental bodies, trade, and immigration.

- The Corporate Arena. Regulation, market structure, consolidation, and societal influence.

- Inequality and Activism. Citizen engagement and governmental response.

- Attitudes Toward Climate Change and Pollution. Policy and approaches.

- The Impact of Technology. Innovation, security, and adoption.

- Money and Finance. Monetary policy, payment systems, and investment climate.

These can play out in numerous ways, especially since they are intertwined and influence one another. Rather than anticipate every potential outcome, a strong scenario exercise should encourage organizations to test their strategy against provocative combinations.

We ultimately chose to anchor on the first two areas of uncertainty because they have deep impacts, and we decided to create four core scenarios that are relevant to almost any organization. Then we added elements of each of the four other areas as “spice” to bring them to life and inspire broader testing of a company’s strategy.

Isolation: populism and nationalism unravel globalization and weaken economic growth. The post–World War II world order vanishes. The US withdraws from the WTO, and the organization quickly disintegrates. The EU is barely alive. Governments adopt nationalistic economic policies, restricting immigration, trade, and foreign ownership of assets.

Global companies scale back their overseas presence and lay off workers at home and abroad. At the same time, manufacturers in most countries cannot hire enough workers with the right skills, which accelerates the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics in wealthy nations. Inflation is rampant, exacerbating the effect of unemployment on inequality. A few governments respond by taxing the tech industry and adopting universal basic-income measures. Dwindling faith in many currencies drives the adoption of cryptocurrencies and distributed ledgers.

Implications of the isolation scenario: The European pharma company would be cut off from many markets. In this world of trade barriers, a decision to consolidate manufacturing in the Middle East would not make sense. The company would be better served by moving to a franchise model that involves licensing IP to local manufacturers in their home markets.

Rivalry: US-China power games divide the world and ignite a corporate cold war. Most countries line up behind one country or the other. Trading occurs within these blocs but not between them. Cyber attacks against one another by the US and China and their respective allies are rampant. Growth of the Internet of Things slows. But the cloud continues to flourish. It somewhat paradoxically serves as a safe haven thanks to massive investment in security and privacy by the tech giants.

Lower economic activity and the slowing of infrastructure projects in China put downward pressure on the price of most commodities. Many Latin American and African nations are hit with a double whammy: their economies are slammed by declining commodity prices and slowing investments from China. Almost everywhere, interest rates and expected returns remain low.

In many industries two giants emerge, one for each bloc. They compete fiercely in the few unaligned countries, such as India, which benefits from the attention and experiences strong growth.

Implications of the rivalry scenario: The pharma company could no longer count on an aging population in China to fuel demand, so the Middle East manufacturing option, which is based on scale advantages, once again would not make sense. The company might spin off its businesses in the China bloc, extracting residual value that it would be unlikely to capture otherwise.

Alliance: urgent consensus on climate unlocks global collaboration, but corporate power remains unchecked. Governments respond to citizen activism and widespread protests about climate change after a massive iceberg calves from the West Antarctic ice sheet. They agree to take giant steps to combat carbon emissions, with China, India, and the US fully onboard. Flush with success from these victories, activists expand into other issues, such as pay equity, corporate responsibility, democratic reform, and single-payer health care in the US.

Nations strengthen regulations to prevent future financial crises. The measures, though successful, reduce leverage and financial flexibility. With so much capital tied up to curb emissions, interest rates rise and some companies struggle to secure financing.

Advances in AI, augmented reality, and robotics boost productivity, enabling new ways of working, shortening workweeks, and reducing travel and commuting. But many workers earn less than before, so these changes are not universally popular.

Implications of the alliance scenario: The pharma company would benefit from the broader public access to health care and, with its focus on R&D and patients, from widespread acceptance of value-based health care that rewards positive outcomes. Lower costs from the global manufacturing facility in the Middle East would help offset the impact of price controls in some markets. As carbon taxes rise, this net-zero facility would have growing cost advantages.

Contest: government action breaks up corporate giants, opening markets and borders and energizing competition. Frustrated by the concentration of power in tech and other industries, governments don’t just split up the biggest companies. They also open their borders and dismantle IP protections to spark innovation and competition. The most resourceful companies continue to find ways to stay one step ahead of their competitors. Economic growth surges.

Open borders create fierce competition for talent. A merit-based elite emerges. A vibrant corporate landscape generates the need for work but not job security as the employee-light gig economy takes hold along with everything-as-a-service. The most successful gig economy workers have financial security and work-life balance, but the less skilled are left struggling to make ends meet.

Competing for the affluent, cities adopt smart technologies to tackle problems like traffic, noise, and pollution. City leaders favor fleets of self-driving electric vehicles over privately owned cars, representative of a broader move away from durable goods ownership by individuals and many companies.

Implications of the contest scenario: The pharma company’s IP-focused business model would be disrupted by others that copy its innovations. One option would be for the company to double down on R&D investments in the pursuit of personalized medicine that is hard to duplicate. Outsourcing of manufacturing also might make sense, as competition has improved quality and cost beyond that achievable at the Middle East facility.

Whatever the Future May Hold

Made-to-order scenarios typically focus on trends relevant to a particular industry. Our scenarios consider broader uncertainties that affect all companies—the COVID-19 pandemic has vividly and tragically demonstrated the impact that unexpected events can have across industries. Our ready-made scenarios are also designed to facilitate exercises that allow executives to explore strategic implications that are specific to one industry and even a single company. These scenarios allow organizations to stretch and test their strategies, manage risk, and better address whatever the future may hold. The goal is to break free of conventional and linear thinking —to expand the perception of the possible and prepare for the unpredictable.

The scenarios generate powerful, fresh insights without requiring vast time commitments.

These exercises generate powerful, fresh insights without requiring vast time commitments. Within a few hours, an executive team can reap new insights and valuable benefits. Within a couple of days, the team can achieve breakthroughs in their thinking.

Returning to our hypothetical European pharma company, what conclusions could that organization draw from this exercise? Senior leaders recognized that consolidating manufacturing in the Middle Eastern country depended on things staying the same or moving toward alliance. It would backfire under isolation. They also came to understand that, because their company focuses on R&D, manufacturing is a relatively small part of the cost base, while tariff risk is a large concern.

The exercise alerted executives to the risk posed by the lack of manufacturing in the US under isolation and rivalry. To address this concern, the company decided to open a US plant as well as a much smaller manufacturing facility in the Middle East that would supply India and smaller markets and provide surge capacity for its major markets. With excess capacity available in the Middle East, the team also decided to make its facilities in Europe and China as efficient as possible. Finally, the leaders agreed to decentralize the corporate structure around those three markets in order to guard against the emergence of the isolation or rivalry scenarios.

We have used the example of a fictional pharma company, but our experience shows that these scenarios are universally applicable to all companies and even the public sector. Imagine how the Australian national government, as an alternative example, might fare under these scenarios. Isolation would require a strong national industrial policy. Rivalry would force the government to pick sides between the US and China and encourage economic and military self-sufficiency. Alliance could force a radical reordering of Australia’s economy away from coal and oil and toward metals and rare-earth mining. Contest would likely result in the breakup of telecom and other monopolies.

This article provides just a glimpse of what these ready-made scenarios can do. They have a lot more to offer. But they are not a replacement for custom scenarios. They are a streamlined option with high-yield potential. They encourage senior leaders to challenge convention and find competitive advantage amid uncertainty.