This is the third article in a series on the priorities for governments during and beyond the pandemic. The first two articles explored the challenges of restarting economic and societal activity and examined how governments can engineer sustainable rebounds in the economy and society . The last article in the series will reimagine the role of government in the post-COVID-19 world.

Read More About What’s “Beyond the Curve”

Read More About What’s “Beyond the Curve”

- Beyond the Curve: Start Reimagining Government Now

- How to Restart in the Wake of COVID-19

- How Governments Can Galvanize Their Nations for the Rebound

In many countries, COVID-19 stimulus funding may not be benefiting all those it is intended to help. As has happened with fast-track financing packages and bailouts in previous crises, sizable tranches of the funds meant to buoy small businesses, critical industries, and those suddenly unemployed are often misallocated.

The remedy is clear: government leaders must re-engineer their approaches to stimulus funding of all types and do so at pace. They must because there is evidence to suggest that stimulus measures do work to resuscitate battered economies. But the remedy cannot be simply to fix what is broken. It must go far beyond, aiming to build for tomorrow.

The rationales are clear, too: the world is moving inexorably toward new digital norms and environmental urgencies, and COVID-19 will not be humanity’s last large-scale shock. Whereas past stimulus packages have focused on jobs and short-term impact, future iterations must also spur innovation, digitization, and sustainability if they are to support the resilience and prosperity of countries far into the future.

Whereas past stimulus packages have focused on jobs and short-term impact, future iterations must also spur innovation, digitization, and sustainability.

The current pandemic, then, must be viewed as a catalyst for redesigning assistance packages and structures so they are truly “fit for purpose,” benefiting their intended recipients while meeting the tests of oversight committees and vigilant taxpayers.

There is still time to act. Many countries still have first-wave stimulus funds to release, and second waves, perhaps even larger, are highly likely, given the scale of the pandemic’s impact and the prospect of a resurgence of the disease. There are precedents: a decade ago, G20 countries launched second waves to deal with the global financial crisis.

We envision four steps to radically and rapidly overhaul traditional approaches to stimulus funding. First, though, it is important to gauge what is at stake right now.

Biggest Stimulus Packages of All Time

The effective management of public funds is an unenviable challenge at the best of times. But these are no ordinary times. This year, the global economy will almost certainly suffer its worst downturn since the Great Depression. It is not surprising, then, that the stimulus responses to the crisis, measured collectively, represent the largest budgetary intervention ever. As of the end of April 2020, they range from 1% of GDP in India to 36% in Germany. They dwarf the sums extended to cope with the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, when the average outlay was 4% of GDP, compared with 12% for COVID-19-related responses today.

The sheer size of those outlays raises an obvious question: to what extent will they do what they are intended to do? Setting aside the well-publicized flaws in current and prior stimulus approaches, it is useful to probe the fundamentals of typical returns to see whether such funding does in fact help economies rebound. In many cases, the answer is yes: looking at the US, emergency funding disbursed from 2009 to 2011 raised the country’s GDP by 2% to 2.5% more than it would have increased without the funding, according to the International Monetary Fund. Furthermore, government support in the form of investments, transfers, and tax cuts had an average multiplier effect of 1.2 on the US economy, and in some cases as much as a two-times multiplier.

Four Steps to Ensuring the Right Returns

The next question is how to improve those returns and do so for the long term, with the resilience, economic well-being, and sustainability of entire countries in mind. Here are the four steps that we believe can help answer that question.

Aim for an Optimal “Return to Country”

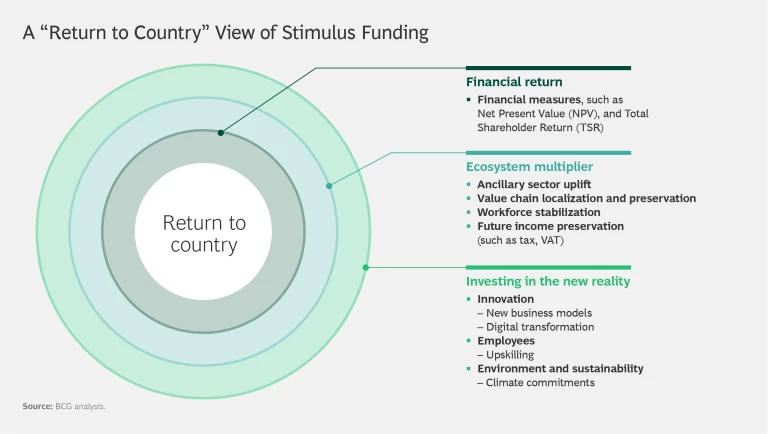

To break from the short-term construct, governments need a broader, longer-term, more comprehensive framework. The concept of “return to country” is a useful start. (See the exhibit.)

The concept includes the conventional financial measures by which stimulus funding has always been gauged. But it calls for a strategic approach that yields enduring, long-term advantages for an entire country. Thinking in terms of return to country can help governments sort among the many calls for support—from individuals and institutions, big corporations and small businesses, multiregional as well as hyperlocal organizations. It also helps tailor the right balance of near-term and long-term measures. The approach depends on several critical actions.

Identify systemically important industries. One of the primary ways to determine the best allocation of funds and the timing of disbursements is to identify the industries that drive economic impact, either through direct contributions to GDP or because they stabilize employment. In many countries, manufacturing is a strategic sector. In Vietnam, for instance, light industrial manufacturing may well be considered strategic in the future as more original equipment manufacturers diversify the risks of sourcing from China. In other countries, strategic scrutiny may accelerate the move toward a knowledge-based economy.

A strategic return-to-country approach requires looking at what is systemically important for a country, and over 10- and 20-year horizons.

That is not to ignore the industries that are immediately vulnerable and will experience lingering effects from COVID-19—for example, hospitality, entertainment, and travel. All have valid claims on stimulus monies, and many have powerful lobbyists to support them. But a strategic return-to-country approach requires looking also at what is systemically important for a country, and over 10- and 20-year horizons. It calls for the evaluation of indirect factors such as the stability and resilience of value chains that may have powerful multiplier effects on demand and consumption. It also entails the assessment of ancillary industries that could gain some uplift from funds targeted at those deemed top priorities.

Acknowledge the new reality. A return-to-country perspective calls on leaders to recognize that societies and economies are moving inexorably toward a new reality—and were doing so before the novel coronavirus emerged. The pandemic is accelerating technology adoption, forcing groups as disparate as school districts and traffic planners to rethink their assumptions. In tandem, it is shining a spotlight on the criticality of innovation and upskilling in healthy economies. Support will be needed—is needed now—for the digital transformations of businesses, institutions, and government itself and for the skills in areas such as data science that will be central to those transformations.

Some countries are moving in this direction: the Monetary Authority of Singapore recently announced funding to sustain and strengthen capabilities in fintech. The package will position fintech firms for stronger growth when the threat of COVID-19 recedes and economic activity resumes.

Embrace sustainability. The return-to-country perspective must include a focus on sustainability—an area of national and international interest. Of the $8.1 trillion in stimulus funding so far approved by the G20 countries, very little is geared to a “green” economy. Canada and Germany are currently the only countries to have even proposed such moves.

A countrywide viewpoint can also go a long way toward ensuring a path toward equitable economic growth. With income and wealth inequality fueling populist movements worldwide, stimulus packages that are actively designed to redress imbalances will be essential to building more-stable societies.

Determine an Optimal Stimulus Design

There is no one-size-fits-all design for the implementation of stimulus funding. What works for the finance industry will apply only in part to the automotive industry. So governments need to envision how to shape their stimulus packages for maximum returns, selecting the right measures for different targets and saving financial “ammunition” for later. We have identified five guiding principles to maximize returns on stimulus spending.

Tailor the stimulus to the target. For example, direct negotiations with government agencies are effective for large companies, while financing mechanisms administered by local banks are often considered best for reaching small and midsize enterprises. Crucially, the package should not be built only around meeting short-term financial metrics but should include conditions for delivering on other objectives of national interest and longer-term growth drivers.

Balance short-term and long-term impact. The timing and the mix of funding mechanisms are important: governments need to structure the stimulus funding with a combination of measures to address economic risks over time and to mitigate the impact on the government’s balance sheet. Different measures work at different speeds; one study shows that tax cuts typically give companies faster relief while public investments and transfers are more likely to spur economic growth in the medium term.

Define clear eligibility criteria. This is more important than ever, given the size and complexity of the pandemic’s effects. The paucity of such criteria has led to regrettable examples of stimulus funding gone wrong. In more than a few cases, stimulus relief has gone to well-funded institutions and corporations that have other avenues for raising money.

Communicate consistently and design simple processes. Effective support requires exemplary communication and processes that can be readily and universally understood and operationalized, not only by target recipients and the agencies funding them but between and among national government bodies and their state- or province-level counterparts. Taxpayers also expect transparent and regular communication about stimulus programs and their longer-term outlook. Communication and process design are areas where government can make big strides; many agencies worldwide can do much more with social media and digital platforms, for example.

Have a clear exit strategy. Well-defined program guidelines and milestones that lead to an agreed-upon end point are essential. For instance, the government will need to lay out the conditions and a timeline for recouping its investments either through exits from the equity positions it might take or from a rigorous measure of impact. For any corporate bailout, it is vital to check the recipient’s fundamental business viability, ensure alignment of incentives, and scrutinize its turnaround plans. For example, disbursement of dividends by companies receiving government support should be carefully controlled. There have also been many instances of taxpayer monies being extended to companies that were already failing.

Germany offers an example of a good exit strategy. In 2017, the German government granted Air Berlin a temporary bridging loan of €150 million as part of the airline’s bailout. The loan terms stated clearly that the goal was to allow for an orderly wind-down of the company so that its closure would not distort competition while protecting the interests of consumers. The deal also required that either the loan was to be repaid in full or the German government would be required to submit a wind-down plan for the company. The bailout succeeded on those terms; most of the airline’s assets and employees were absorbed by competing airlines.

Select the Best Channels for Disbursing Stimulus Funds

No government has the infrastructure to deal with the torrent of requests pouring in from businesses, institutions, and individuals. One consequence is very clear: governments can no longer rely only on traditional channels of distributing emergency funding. They have to embark on a far-reaching redesign of the channels themselves—not only re-engineering the roles of traditional channels but imagining and inventing entirely new ones.

Governments can no longer rely only on traditional channels of distributing emergency funding. They have to embark on a far-reaching redesign of the channels themselves.

In identifying the best channels for each target recipient or target sector, governments must balance three factors: speed, risk, and impact on public trust. The public clamor about monies not arriving in time is ample evidence of the need for speed. It is crucial to minimize both executional risk—associated with making sure funds are used effectively and provided to the right people—and the direct risk that the government bears by providing the stimulus aid in the first place. Governments must also consider the impact of their channel choices on public trust; in some countries, that means a concerted effort to negate perceptions of favoritism, corruption, and cronyism.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed additional challenges. The vastness of the range of beneficiaries is a challenge all by itself, but the diversity of target types and characteristics—from massive multinational corporations to tiny local businesses—adds exceptional complexity. Those challenges apply in different ways to different channels.

- The Financial Sector. Long the preferred route for crisis fund deployment to small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), this channel has a significant downside in light of the three factors noted above: it is difficult to mitigate the natural risk aversion of banks. Use of this channel also depends on the current risk management infrastructure and the strength of governments’ commercial partners. That said, some countries are showing imagination. In the US, the Internal Revenue Service has designed and launched its Get My Payment app, which enables Americans to register, log on, and track the status of their individual stimulus checks. Meanwhile, Peru is expanding the set of permitted financial service providers to include mobile money providers in order to reach additional beneficiaries. And Brazil is providing millions of previously unbanked citizens with smartphone-based savings accounts held by government-owned bank Caixa Econômica Federal. Under the scheme, citizens can register to receive the COVID-19 relief through a website or an app.

- Direct Financing. This channel enables fast access to funding and gives governments more control over implementation. However, direct financing is applicable only in very specific circumstances and comes with a high risk of the perception of favoritism.

- Regional Development Funds or Banks. These already exist in many countries and often have the capabilities, reach, and mandate to support broader and longer-term objectives.

- Distressed Asset Funds. This channel, used to purchase toxic assets and equity from companies, deserves re-examination. Although such funds can produce high returns, setting them up requires time and deep expertise, so their effectiveness depends on government’s ability to leverage existing infrastructure. Further, the tendency has been to reinvent the wheel for each new crisis. Far better to routinize this channel for the inevitable crises to come.

There is no shortage of funding channels, and governments must use all of them, as appropriate. But that cannot be the extent of the routes for getting monies to target industries, companies, and individuals. This is an opportunity for government to innovate to ensure preparedness and resilience for new waves of funding during the COVID-19 pandemic and to deal with future crises. Digital tools of all types, fintech innovations, and new communication channels must be considered and implemented for tasks ranging from the fundamental, such as how to advise applicants on correctly applying for assistance, to the more complex, such as rapidly determining eligibility for a wide variety of applicants. The technology actions do not have to be sophisticated; Japan is blazing trails with a program to subsidize IT investments for SMEs to shift to teleworking and e-commerce. Japan views the program as an initiative that will add value to the country’s economy over the long term.

Deploy a Best-Practice Governance Structure

Historically, governments’ treasury departments have led emergency funding packages. But in this case, past should not be precedent. The return-to-country perspective indicates the value of a cross-government and beyond-government approach—an ecosystem approach to the governance of stimulus funding, in effect.

Increasingly, though, governments need to put in place the right governance to convince their constituents that everything possible is being done to protect taxpayers’ money and ensure sound government balance sheets for future generations. Trust in government matters more than ever—it is clearly revealed as a key factor in the ability of various countries to engage their populations in COVID-19 responses. Trust should be a component of every government’s long-term return-to-country approach to stimulus funding.

There are constants to good governance: clear and measurable criteria; regular monitoring and evaluation; enforcement and accountability; and transparency. Beyond those basics, strong governance frameworks share several elements.

Oversight Authority. This typically resides in a committee of senior public sector officials and often includes some private sector representatives. Effective oversight comprises approval for major decisions, reviews of progress and updates, communicating progress to and providing transparency for the public, and establishing the defined and measurable criteria mentioned above. This “watchdog” function is common and effective in many countries. However, it bears emphasis these days because there are signs of pushback against oversight activities. If trust and transparency are to be linchpins of the broader vision embodied by the return-to-country concept, oversight authority must be strengthened, not weakened.

Financial and Fiscal Monitoring. A country’s central bank and treasury typically coordinate with the oversight panel on eligibility criteria and major disbursements and ensure that the funds are successfully deployed, among many other activities.

Executional Taskforces. Each one is focused on an industry, for example, and has a deep understanding of its sector and is able to engage relevant stakeholders. Again, such organizational bodies are not new. But what is different now, amid a crisis whose duration and eventual impact are as yet unknowable, is that the organization of such taskforces will need to be much more agile and inclusive of the relevant stakeholders to underscore a return-to-country perspective.

That may require unconventional matrixed organization structures, in which the oversight panel and specific taskforces have multiple dotted-line relationships and there are similar links with treasuries and central banks and quite possibly with environmental and labor agencies. Such fluid and dynamic organizational linkages lend themselves to digital tools for tasks such as resource coordination and rapid scenario modeling.

Now is the time for governments to mobilize to ensure that stimulus responses do what they are intended to do. But the new stimulus constructs must not simply be modified versions of what was; they have to be radically, urgently re-engineered for what will be.

The governments that act with urgency and determination will find ways to assess the robustness of their current stimulus approaches. They will enhance their actions with learnings and best practices, and they will develop checklists in order to stay on track. In doing so, they will ensure that their stimulus funding is geared to maximize return to country.

They will not only be setting up their economies and societies to withstand the next crisis—they will be building the structures essential to the resilient, confident nations of the far future. Taxpayers—and voters—will applaud them for it.