CEOs face a host of challenges in even the best of times, from setting strategic direction to ensuring the organization is reaching its full potential to engaging internal and external stakeholders effectively—all while taking accountability for performance and serving as the company’s main spokesperson. These responsibilities become even more complex in a crisis like the COVID-19 epidemic, as employees and stakeholders turn to CEOs for direction, information, and motivation.

With such a spotlight on leadership, it’s worth stepping back to understand CEOs’ role in company performance. Just how much impact do CEOs have on their firms? To what extent does this “CEO effect” depend on context? And what separates top-performing CEOs from the rest?

To answer these questions, we studied the tenures of 7,000 CEOs worldwide to identify how much and how they affected their companies’ performance trajectories. We looked at the sustained effect of each CEO on the firm’s total shareholder return (TSR) relative to peers, controlling for year, industry, and prior firm performance. (See “Our Methodology.”)

Our Methodology

Our Methodology

We analyzed CEOs in BoardEx’s database that led companies with at least $50 million in inflation-adjusted sales from 1985 to 2018. CEOs were excluded if they did not stay at the company for at least three years.

To estimate the CEO effect, we built a model regressing annual TSR outperformance on control variables for year, industry, and starting position, as well as an indicator variable for each CEO. We control for year and industry using indicator variables for each year and industry average outperformance for each year-industry pair. To control for prior firm performance, we use a two-year trailing average TSR outperformance prior to the start of the CEO’s tenure. To remove the impact of extreme outliers, the top and bottom 5% of performers are winsorized.

The value of the coefficients for each CEO indicator variable then represents the CEO effect, or the sustained, annual impact on TSR, controlling for industry and other factors, throughout a CEO’s tenure.

In summary, our research shows the following:

- New CEOs often cause a significant, sustained change in performance. The companies of the top 20% of CEOs outperformed their sector by 9 percentage points per year over the course of their tenure, controlling for other factors, whereas the companies of the bottom 20% underperformed by 11 points.

- The spread of CEO impact varies by strategic context. The gap between the most and the least successful CEOs is up to 9 points wider in fast-growing, technology-driven businesses than in slower-growing, more-regulated contexts.

- The CEO effect tends to decline with scale. The performance spread caused by the CEO effect is greater among smaller firms (driven largely by a higher potential upside), but a significant spread exists in companies of all sizes.

- Some actions are associated with CEO success across nearly all contexts. Top-performing CEOs are more likely to take a long-term approach to strategy, accelerate M&A activity, increase their company’s ESG scores, and pay more attention to diversity.

- Others are associated with success only in specific contexts. For example, when taking on a severely underperforming company, CEOs are more likely to be successful if they change out more of their reports. Additionally, among leaders who launched corporate transformations, those that did so in the first or second year outperformed those who waited longer.

- Most personal CEO traits (including hire type, prior CEO experience, gender, age, and education) have no impact on average performance. However, they can affect the risk profile: for example, external hires have a greater spread of outcomes.

- Personality has a limited impact on success. Based on an outside-in assessment of CEOs’ personality traits using natural language processing techniques, we observe that no profile guarantees or precludes success.

Analyzing the CEO Effect

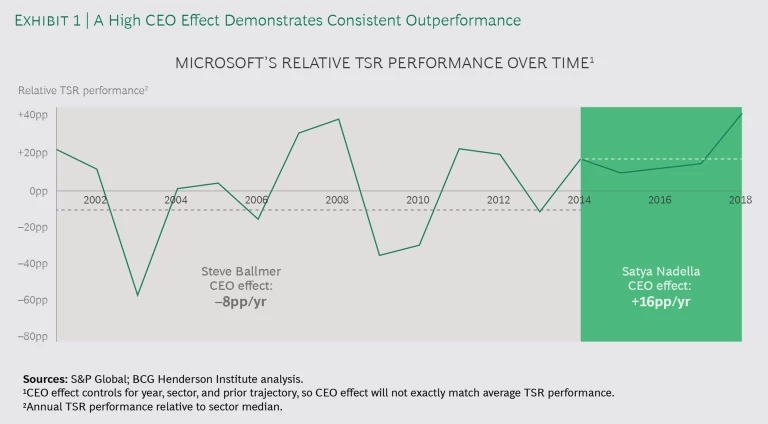

The arrival of a new CEO often marks a sustained change in firm performance. The best among them, defined as those with a top-quintile CEO effect, increase TSR outperformance by at least 9 points annually throughout their tenure. Consider Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s CEO since 2014. Faced with Windows’ declining market share, Nadella accelerated Microsoft’s shift to a cloud-based business model and completed several major acquisitions. Controlling for the company’s industry and starting position, Nadella has had a positive impact of 16 points annually throughout his tenure. (See Exhibit 1.)

Haishan Liang of Haier Smart Home is another example. As CEO of the smart home products manufacturer, Liang grew the firm’s IoT data ecosystem by entering a strategic partnership with Baidu, acquired GE Appliances in 2016, and renamed and repositioned the firm as the orchestrator of a home device ecosystem. Since the start of Liang’s tenure, in 2013, the firm’s market capitalization has more than doubled.

Some CEO tenures, however, are marked by a similarly strong negative impact on performance. CEOs in the bottom quintile have a -11-point impact annually, after adjusting for other factors. We can express the impact of CEO leadership as the spread between top- and bottom-quintile CEOs. Overall, this is 20 percentage points per year—which, over the median CEO tenure of six years, accumulates to a gap larger than the value of the company at the start of the CEO’s tenure.

However, the CEO effect varies by context. As an example, it is generally larger in dynamic, fast-growing sectors. In IT, communications services (including internet services), and consumer discretionary (including digital entertainment and internet retail), the spread of the CEO effect is 23 points, compared with 14 to 17 points in more-regulated and slower-growing industries (real estate, utilities, and financial services). This may reflect the fact that faster-growing environments are more malleable —leaders can shape the market more easily than they can in highly regulated or slow-growth environments.

The CEO effect is generally larger in dynamic, fast-growing sectors.

Industry classifications may not fully contextualize the CEO effect, however, as the patterns of value generation and starting positions of firms vary widely within and across industries. This is increasingly so as digital technology facilitates competition and collaboration across industries. Our prior research has identified ten common value patterns , which describe how a company’s position at a given point determines the range and types of strategic moves most likely to create value. (See “Detail on Value Patterns.”)

Details on Value Patterns

Details on Value Patterns

When considering the CEO effect through this lens, a similar theme emerges. CEOs have the largest impact when they take on companies in high-growth, technology-intensive contexts: those with Healthy High-Growth and Asset-Light Services value patterns. These CEOs have the largest spread in CEO impact (23 to 25 points). In contrast, CEOs tend to have less impact when inheriting High-Value Brands, which are characterized by the generation of stable returns from established brand assets, and Discovery firms, which are characterized by long-cycle, bottom-up innovation.

Another factor in the CEO effect is the size of an organization. Among the largest companies in our sample, those with more than $50 billion in annual inflation-adjusted revenue, the spread between top- and bottom-quintile CEO effects is 15 points, whereas companies with revenue of $5 billion to $50 billion have a spread of 17 points, and the smallest companies have an even greater spread. This is driven by higher upside for top-quintile CEOs in smaller companies; the downside of underperforming CEOs is similar across size groups. This reflects the fact that extraordinary returns are more likely to be generated from a smaller base, as well as the fact that sustainable reinvention becomes harder as companies age and grow .

If history is any guide, the current crisis may be accompanied by a wave of new CEOs.

Finally, if history is any guide, the current crisis may be accompanied by a wave of new CEOs—it is perhaps no surprise that the financial crisis of 2008 also saw a peak in CEO turnover, with nearly 20% of leaders departing that year. Evidence shows that the impact of CEOs’ performance rose slightly in the past two downturns, driven more by a greater downside for underperforming leaders. However, the upside for top CEOs remained just as high as in other circumstances, in terms of their impact on relative performance, reminding us that advantage can be found in adversity .

For example, Jim Whitehurst took over Red Hat at the start of the last recession. With IT budgets slashed, corporate customers, initially wary of the shift away from familiar enterprise solutions, gave Red Hat’s less expensive open-source solutions a second look. Under Whitehurst, Red Hat capitalized on this opportunity, signing up customers for longer-term deals and investing in emerging technologies such as cloud computing and virtualization. As a result, Red Hat emerged from the global financial crisis with double-digit revenue growth, a trend it continued until its acquisition in 2019 by IBM.

The Success Factors for CEO Performance

Given the sustained impact that CEOs can have on their companies’ trajectories (for better or for worse), it is important to know how they can tilt the odds in their favor. By using financial and nonfinancial signals to identify the different moves that CEOs have made, we can identify which factors set successful leaders apart from unsuccessful ones.

A few success factors are associated with high CEO performance across all contexts:

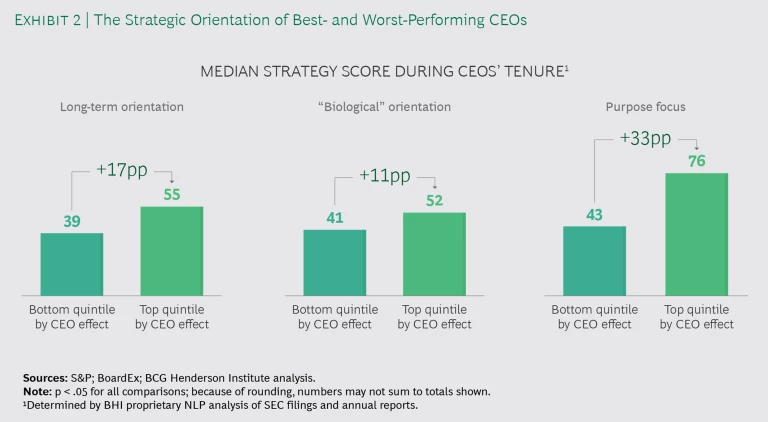

They take a long-term, externally oriented approach to strategy. The top-performing CEOs drive excellence in strategic thinking. Based on a proprietary natural language processing analysis of SEC filings and annual reports, our research indicates that top CEOs preside over organizations that stand apart from peers on several dimensions: long-term orientation, which indicates a strategic focus on the firm’s future as well as the present; “ biological thinking ,” a measure of the adaptiveness, flexibility, and mutualism best-suited to a complex and dynamic business environment; and a focus on purpose, an approach to strategy that extends beyond financial performance and matches a firm’s capabilities and aspirations with societal needs. (See Exhibit 2.)

One such CEO is Kasper Rorsted of Adidas. As CEO, Rorsted has embraced a long-term strategic orientation, emphasizing that the key to Adidas’s global sourcing model is its long-term relationships with suppliers . At the end of 2018, 84% of Adidas’s strategic suppliers had worked with the company for more than 10 years and 42% for over 20 years. Since the start of 2016, Rorsted has had a positive annual impact on performance of 25 points.

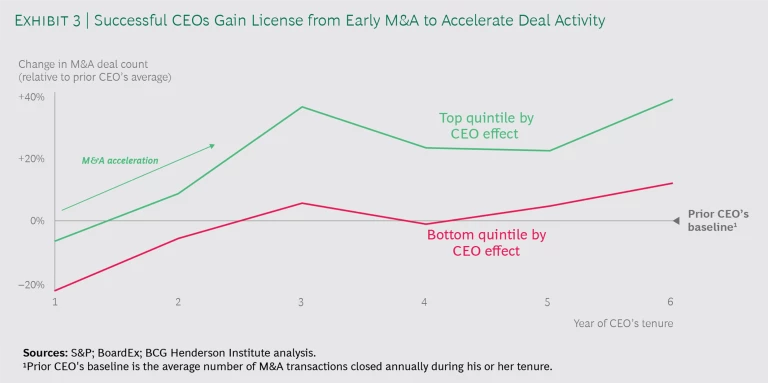

They accelerate M&A activity. Relative to their predecessors, top-quintile CEOs accelerated acquisition activity by an average of 15% throughout their tenure. Bottom-quintile CEOs, in contrast, decelerated acquisition activity by an average of 7%. While poor-performing CEOs tend to immediately decelerate M&A, successful CEOs, in contrast, tend to initially maintain a similar level of deal activity as their predecessor. Then, having gained the license to do more, they accelerate and sustain elevated levels of deal activity. This suggests successful CEOs take a more activist approach to capital allocation. (See Exhibit 3.)

Ronnie Leten, one such example, led Atlas Copco, the Nordics’ largest industrials firm, from 2009 to 2017. In his first letter to shareholders , Leten outlined a strategy to achieve one-third of the company’s growth through acquisitions. In his first 18 months, Leten maintained a similar deal cadence as his predecessor, acquiring nine firms with Kr1.4 billion in sales in total at the time of acquisition. Then he dramatically accelerated M&A, acquiring three dozen firms with Kr12 billion in sales over the next four years. The company’s market capitalization quadrupled over his eight-year tenure as CEO.

They emphasize nonfinancial in addition to financial performance. In line with the increased focus by investors and other stakeholders on nonfinancial performance, the average company has been improving its ESG (environmental, social, and governance) performance over the past 15 years. However, we find that successful CEOs are increasing their companies’ ESG scores at twice the rate of bottom-quintile CEOs. This may be a byproduct of overall competence, as underperforming CEOs may not have as much bandwidth to focus on nonfinancial factors, or it could be that a focus on ESG is a driver of sustained outperformance in its own right, since doing well on important social issues is good for sustainable value generation in the long run. By whichever mechanism, the best CEOs create not only good fundamentals and stock price performance, but also a lasting legacy .

Breaking ESG down into its components, the best-performing CEOs did especially well on governance—perhaps not surprising given the unique role that CEOs play in setting the organizational model. Specifically, in alignment with recent increased interest in multistakeholder governance models, they improve CSR strategy and management scores, instead of focusing narrowly on shareholder-related issues.

John Chambers, the CEO of Cisco from 1995 to 2015, is one such example. As CEO, Chambers increased the company’s market capitalization from $8 billion to more than $144 billion while remaining deeply committed to creating social value. During his tenure, Cisco founded the Networking Academy, an IT skills- and career-building program aimed at teaching students the skills required to design, build, manage, and secure networks. In 2017, the program celebrated its 20th anniversary, boasting 7.8 million students in 180 countries.

They pay more attention to diversity. A more diverse workforce generates a wider range of ideas and therefore more innovation potential , which is especially necessary in a business environment in which competitive advantage has become less persistent .

For CEOs that take over large companies, it is difficult to make instant progress in changing the composition of the workforce. However, a leading indicator of progress on diversity is the composition of new hires under a CEO’s tenure. Although gender parity remains elusive in even the most diverse firms, top-performing CEOs increase the percentage of female new hires (from 36% to 38%), while bottom-quintile CEOs oversee a slight decline (from 31% to 30%). Gender diversity is only one of many dimensions of diversity that matter, of course, but it is the one for which data is mostly widely available, and we hypothesize that top-performing CEOs pay more attention to diversity more broadly.

Success Factors in Specific Contexts

While a handful of factors align with strong CEO performance across all contexts, the impact of other strategic moves varies by context.

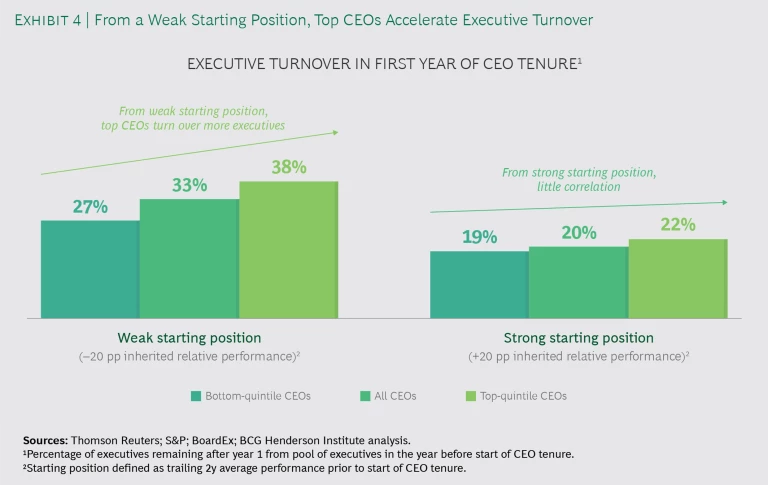

On average, 27% of senior executives exit by the end of the first year under a new CEO. Not surprisingly, from a weak company starting position (characterized by two-year TSR underperformance of 20 points or more), early executive turnover rates rise to 33%. But CEOs that successfully turn around a weak company have the highest rate of turnover, seeing 38% of executives exit by the end of their first year. In contrast, there is no difference in turnover between successful and unsuccessful CEOs who inherit a strong starting position. (See Exhibit 4.)

Corporate transformations represent yet another avenue for new CEOs to leave their mark. Our research shows that transformation is difficult and that the majority of such initiatives fail to create value, in large part because most companies, rather than changing preemptively, wait until they have no choice but to do so, and as a result lack the time and freedom needed to pursue longer-term moves.

When corporate transformation is necessary, CEOs who recognize the need for change early in their tenure and act swiftly tend to have more success than those who wait. Among CEOs who launched transformations, those that did so in the first or second year outperformed those who waited longer by 3 points annually. (This is consistent with earlier evidence that fresh leadership improves the odds of a successful change effort.)

CEOs’ Personal Characteristics

We may have a stereotypical image of a successful leader. In most instances, however, the demographic background of a CEO tends to have no observed impact on the odds of success. For example, we observe no significant difference in CEO impact as a result of gender. However, one variable that does matter is the hiring route. CEOs hired externally tend to perform no better or worse than those hired internally on average, but they do have a wider spread of outcomes.

CEOs hired externally tend to perform no better or worse than those hired internally on average, but they do have a wider spread of outcomes.

Beyond demographic factors, it is plausible that the personality traits of CEOs might influence success. Motivated by recent research that demonstrated that Big Five personality scores can be reliably inferred from CEOs’ language when discussing their companies, we used machine learning to infer the traits of CEOs from responses given during the Q&A portion of quarterly earnings calls.

We found that, overall, CEOs of all personality types could be successful, and on almost all dimensions there was little gap between the best- and worst-performing leaders. Put another way, we found no personality profile that either guaranteed or precluded success.

However, one area stood out: underperforming CEOs were more likely to score high on the Conscientiousness dimension. While this personality trait implies reliability and diligence, it also connotes a preference for goal-directed planning, which comes at the expense of spontaneity, adaptability, and agility.

Implications

While every CEO tenure is different, our findings suggest that there is a pattern of moves and characteristics that tend to improve the odds of success. Together, they point to some leadership principles:

1. Strive to defy the average. Though the magnitude of the CEO effect can be greater in some contexts than in others, there is a significant gap between the top and bottom CEOs in every industry and type of company. This is consistent with earlier evidence that the spread of performance between companies in a given industry is much greater than the spread of performance between industries . As a result, leaders should focus less on “best practices” (which tend to level performance) and more on innovation and new opportunities in order to be exceptional and defy the average. Strategy is often conducted with the assumption that sector is a significant determinant of a company’s fate, but the evidence suggests otherwise.

There is significant competitive advantage to be gained even in times of crisis. In economic downturns, competitive volatility increases, and 14% of companies increase both revenue growth and margin in absolute terms. Furthermore, the evidence indicates that a long-term, growth-oriented perspective is important to emerging from a downturn stronger. Amid the current crisis, leaders should not focus only on weathering the storm but also on taking advantage of new opportunities and reimagining their businesses for the future . In other words, a downturn is a better opportunity for creating competitive advantage than more stable times.

2. Identify key moves and act preemptively. A common theme among successful CEOs is that they took early action where necessary—they accelerated turnover in underperforming management teams, they weren’t hesitant to make deals early in their tenure, and they embarked on transforming their organizations early when needed.

Even for long-tenured CEOs, there is value in preemptively initiating change . But whereas new leaders often come in with a fresh perspective and a burning platform, incumbent leaders need to fight harder to avoid complacency or inertia in order to recognize and mobilize against new threats.

3. Take a de-averaged and dynamic approach to strategy.Traditionally, the role of corporate leaders has often been to set clear goals and define unchanging plans to achieve them. However, in an increasingly uncertain and fast-moving context, classical planning processes are not always the best approach. Accordingly, leaders that are overly “goal-oriented” have tended to perform worse, especially in disrupted industries. Instead, the most successful leaders are more likely to adopt the right approach to strategy in each part of the business , and in particular to use dynamic and/or creative approaches where necessary.

4. Articulate and fulfill a positive social purpose. Increasingly, top CEOs are being called on to serve a broader range of stakeholders than shareholders alone, and in the long run businesses must create value for society in order to continue to attract talent, customers, and capital. The most successful CEOs attend to these issues by articulating a purpose beyond maximizing financial returns and by improving performance on nonfinancial dimensions. The expectations of the social contributions of corporations are increasing, and leaders will increasingly need to pursue sustainable business model innovation to co-optimize for business and societal benefits.