For incumbent power and gas utilities, the prospect of retail-market liberalization—currently underway in such countries as Japan, Israel, Malaysia, and Mexico—can evoke a shudder. The impact of liberalization on the business can, in fact, be jarring, particularly in the early stages of the market’s opening. New competition—both from established players and from upstarts outside the industry—enters the fray, chipping away at incumbents’ pricing power. Meanwhile, some share of customers inevitably defects. Business as usual, with its steady, predictable cash flows and profits, rapidly becomes a thing of the past.

But market liberalization need not be an existential threat to incumbents. By rethinking their business model and relationship with customers and moving aggressively and proactively, incumbents can boost their resiliency against liberalization’s shorter-term effects and position themselves for longer-term success. But acting now is paramount. Liberalized markets evolve more quickly in today’s digital-centric business environment than ever before; incumbents cannot afford to take a wait-and-see approach.

Rising Competition and Its Effects

Every retail energy market’s liberalization journey is unique. Starting points vary widely. When France commenced liberalization, for example, the country’s power and gas markets each had only one major incumbent. In the UK and Germany, in contrast, markets comprised many regional utilities.

Markets also differ considerably in the pace of deregulation. Chile launched the opening of its power market in the mid-1980s but has yet to extend liberalization fully to all customers. The UK, meanwhile, completely deregulated its retail power market within a decade.

Markets also vary in how deregulation unfolds. When Germany liberalized its power market, all end users were given the latitude to choose freely among energy retailers simultaneously. In the UK, liberalization proceeded in stages, with the largest industrial users permitted to choose among providers first, followed by companies with smaller energy demand and then, finally, remaining business and residential consumers.

These variations notwithstanding, liberalizing markets typically share common traits. One of the most noteworthy is the ways in which the business (B2B) and residential (B2C) customer segments differ in terms of the effects of rising competition.

Business Customers

In the B2B segment, competition generally grows quickly once liberalization has begun. This is owing to a combination of factors: the increased visibility into prices that B2B consumers gain through the new, liquid exchange markets that deregulation typically spawns, coupled with the launch of tenders by B2B companies’ professional procurement departments once their existing contracts expire. In addition, new market entrants can buy energy directly in the new exchange markets, lowering a potential barrier to entry. And the growing prevalence of power purchase agreements between producers and retailers lowers the barriers to entry for new players even further.

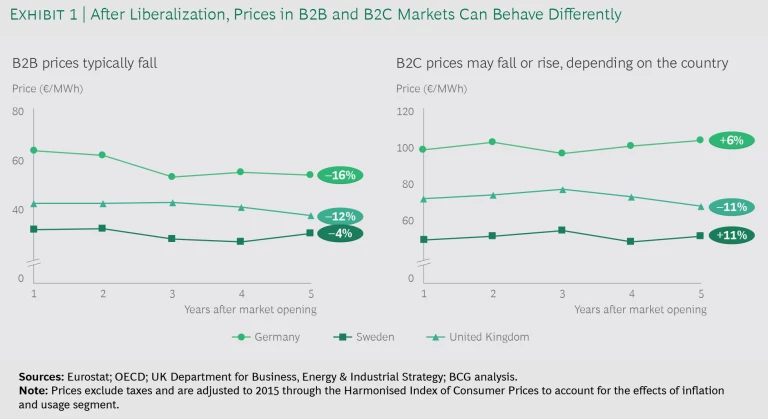

The growth in competition has two key results. First, retail prices fall in the first few years, largely driven by aggressive pricing by new entrants (as well as by potentially falling wholesale prices). Germany’s example is a case in point: five years after deregulation, electricity prices for industrial users were 16% lower. The decrease in prices tends to be substantially greater than in B2C markets , where in some countries prices actually increase. (See Exhibit 1.)

Second, incumbents’ market share decreases considerably. For example, ten years after Ireland liberalized its power market, Electric Ireland had lost more than half of its previous share of large energy users. Incumbents’ loss is often new entrants’ gain; in Texas, MP2 Energy has been able to capture more than 5% of the small- and medium-enterprise market. But many new entrants struggle in the liberalized B2B segment because of the fierce competition and low margins. First Utility (now Shell Energy), for instance, ultimately chose to exit the segment in the UK and focus on the residential market. The loss of market share by incumbents is accompanied by high switching rates (15% to 25%) among customers in many markets (including Italy, Norway, Spain, and the UK) in the medium to long term.

Residential Customers

Competition generally grows more slowly in the B2C segment. One contributing factor is the failure of some governments to aggressively spur competition. Some also attempt to shield residents from price volatility and, in particular, the potential for rising prices. Additionally, residential consumers tend to be less likely to change providers in pursuit of lower prices than industrial users. This is mainly because the utility bill of most residents is a relatively small portion of their total monthly expenditures, reducing the motivation to seek out lower prices.

These dynamics have distinct effects on the evolution of retail prices. As noted, prices do not show the substantial downward slide common in B2B markets; indeed, prices may even rise, especially if the prevailing rate before liberalization was held artificially low by government subsidies.

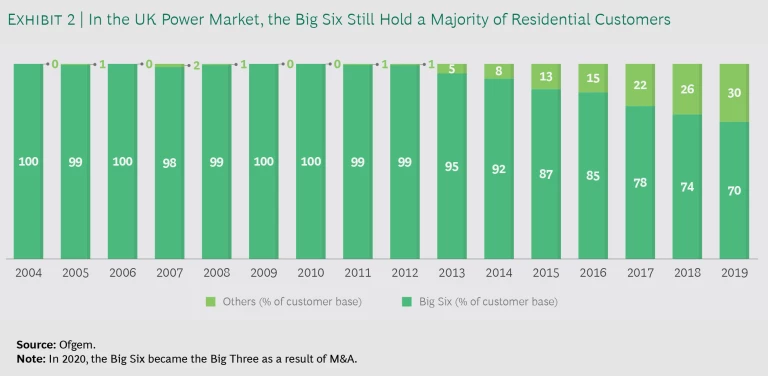

In parallel, while incumbents do lose market share, it is to a much smaller degree and at a much slower pace than in the B2B space. Years after deregulation, incumbents are likely to have suffered a market share decline of only 10% to 25%. Even in the UK, one of the most mature liberalized markets, incumbents still hold roughly a 70% share. (See Exhibit 2.)

This is not to say that new entrants do not try to gain a foothold in liberalized residential markets. Indeed, some new entrants will sell below cost in an effort to win customers. Some also lower their prices aggressively when wholesale prices fall, though this strategy often backfires when wholesale prices subsequently rise, given many companies’ lack of financial muscle. The UK, for example, has witnessed a wave of related bankruptcies in the last few years, with ten in 2018 and another eight in 2019.

The tendency of residential customers to switch providers in the immediate wake of liberalization differs by country and state. But in most mature markets (for example, the Netherlands, Norway, Texas in the US, and Victoria in Australia), it tends to settle at 10% to 15% of customers in the medium to long term. “Stickiness,” or the reluctance to change providers in pursuit of lower prices, in the residential segment is generally diminishing, owing in large part to the greater price visibility afforded by price comparison websites. But some stickiness remains, and energy regulators in some countries (including the UK and Australia) are actively stepping in to try to counter it.

On balance, we think that the various forces influencing B2C markets will cause liberalization to proceed at a faster pace than in the past.

Countering the Threat, Positioning for the Future

The strategies and tactics that incumbents need to pursue in the B2B and B2C spaces will hinge on their specific needs, opportunities, and strengths.

Actions for Incumbents Serving Business Customers

In the B2B arena, many incumbents will need to completely refocus their business. In extreme cases, some may be well served by partially or completely eliminating their exposure to large B2B businesses. Germany’s EnBW, for example, completely cut its exposure to larger B2B commodity businesses, a move that contributed to an upward adjustment of 32% to the company’s EBITDA in 2017. But there are other moves worth exploring as well.

Cost Reduction. Many incumbents need to reduce their operating expenditures, and they have a variety of ways to do so. For example, they can reduce customer acquisition costs by standardizing their offering to small B2B clients; developing a multichannel strategy that aggressively leverages digital capabilities; decreasing the number of key account managers; increasing the use of inside sales to identify and pursue potential small and medium-size clients; and automating administrative sales processes, such as those that support offer preparation and pricing calculations.

Incumbents can reduce customer service costs by developing and simplifying their online access portal and redirecting small B2B clients to self-service support channels; tackling the root causes of customer-initiated contact; improving screening for bad debt during the customer acquisition process; upgrading processes for the collection and sale of bad debt when customers default; and moving customers to prepaid service offerings.

In the B2B arena, many incumbents will need to completely refocus their business.

Finally, incumbents can reduce overhead costs by automating back-office processes, such as billing and dunning, and mutualizing overhead functions (such as finance, HR, and legal) with the corporate partner.

Pricing. Optimized pricing for large B2B clients starts with getting the cost calculation right. This means accurately determining all relevant costs, especially risk-related ones, such as costs related to forecasting risk (a customer might demand energy at different times than projected—more during expensive daytime hours and less during the night, for instance) and costs related to volume flexibility risk (a customer might demand more energy than anticipated, forcing the retailer to buy more supply on potentially higher-priced spot markets).

Getting pricing right for smaller B2B clients requires the use of pricing analytics. Price sensitivity among these clients can differ considerably, and having a strong sense of a given client’s potential lifetime value can help greatly in setting realistic prices. Smart pricing can ultimately deliver substantial benefits to incumbents, including improvements of up to 10% in gross margin, in our experience.

Profitability Maximization. Detailed analyses of B2B customer segments often show enormous differences in profitability. Incumbents should focus on net (not gross) margins in decision making and act aggressively once low-profitability clients have been identified—by increasing prices, for example, charging for specific services (such as the issuance of paper invoices), or adjusting service levels.

Utilities often face difficulties in profitably serving energy-intensive industries, such as mining, low-volume small and medium-size enterprises, businesses with multiple sites (including many telecom providers), real estate managers, and the public sector (including schools). Exiting certain segments is often a valid decision.

New Products and Services. Creating a platform that efficiently supports the development and launch of new products and services may be critical to many incumbents’ long-term prospects. But developing that platform can be challenging, as it falls beyond the expertise of most players, whose focus has been on the provision of commodity-like offerings.

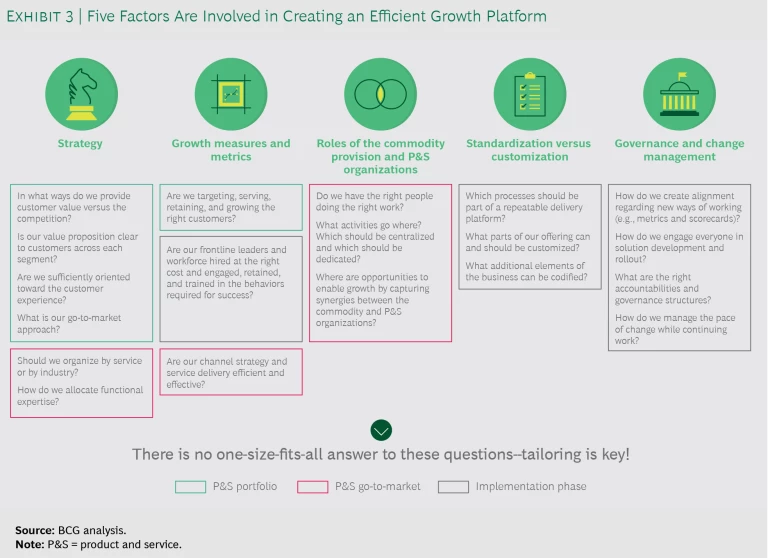

As shown in Exhibit 3, making such a platform a reality demands success on five fronts:

- Development of the right strategy (How are we going to add customer value versus the competition?) and organizational structure (Should we organize by type of offering or industry served?)

- Design of effective growth measures (Are we targeting the right customers?) and use of the right metrics (How should we measure efficiency?)

- Delineation of the respective roles of the product and service organization and the commodity provision organization (Do we have the right people doing the right work? Are there potential synergies that we are overlooking?)

- Hard choices on the mix of customization and standardization

- Optimized governance structure and change management processes (How can we engage everyone in the design and rollout of new offerings?)

One large Spanish B2B incumbent successfully created such a platform. The company’s focus was on providing specific industries with tailored solutions (for example, support of large-scale laundry facilities at hotel chains) and offering energy-specific service bundles that included investment in capex on the client’s behalf (to reduce clients’ upfront expenditures), equipment installation and maintenance, and long-term (5- to 15-year) contracts.

Actions for Incumbents Serving Residential Customers

In B2C, liberalization will not weaken an incumbent’s business fundamentally, provided the company takes proactive measures to defend its business against attackers in the near term and to position itself intelligently in order to capture medium- and longer-term growth opportunities. We recommend that incumbents facing liberalization take action on five fronts.

Cost to Serve. Typically this comprises billing and payment costs, costs per customer contact, and other costs related to servicing customers. Reducing customer-servicing costs will be critical in the face of emerging lean and digital-based competition. It can be accomplished by deploying a combination of classical levers (for example, greater use of outsourcing or the shifting of customers to direct debit payments) and digital levers (such as reducing customer contact costs by using software robots to support agents and increase customers’ ability to self-serve).

Sales and Acquisition. Once established, sales and customer acquisition channels, including the online channel, physical stores, and call center operations, should be optimized to the extent possible. Incumbents should strive to make online their primary channel for sales and customer acquisition. Customers are increasingly biased toward the online option because of its convenience; retailers can build the necessary capabilities relatively cheaply, especially those accessed and delivered via the company’s website.

Incumbents should reorient physical stores away from service and toward sales, and they should reduce the number of stores where possible. In cases where stores are retained, they should emphasize flagship stores in premium locations. And they should optimize door-to-door sales efforts by using analytics to identify the most promising geographic areas and by linking agents’ remuneration to sales success.

Call center operations span both outbound and inbound calls. Outbound calls can be an important source of growth in sales and customer acquisition. But take care to ensure compliance with local laws and regulations. Some jurisdictions, for example, forbid cold calling residential consumers.

In B2C, liberalization will not weaken an incumbent’s business fundamentally, provided the company takes proactive measures.

Customer Retention. Make an effort to understand which events—an incorrect bill, a bad customer service experience, a customer relocation—are most likely to trigger defections at each stage of the customer life cycle and identify appropriate preventive measures.

Not all customers are equal, however. Use analytics to identify the most valuable customers, as well as those most likely to defect. Prioritize retention efforts accordingly, and act proactively to retain the most valuable at-risk customers, such as by offering a lower price or different contract terms.

Incumbents should also recognize that, at the end of the day, the most potent tool for retaining customers is to afford them a positive experience. Management should foster that message internally so that the right culture is instilled and reinforced.

A Seamless, Omnichannel Customer Experience. Incumbents should have a credible presence in all channels, including the call center, traditional mail, email, chat, social media, mobile, and internet. Customers should be able to jump between and among channels effortlessly and with seamless support and communication. One European energy company can detect, via an algorithm, when a customer or prospect surfing its website has failed to find the information he or she is looking for; a chat window, staffed by a human agent, then quickly opens to provide support.

Developing such omnichannel capabilities demands the ability to flexibly integrate channels and systems so that the ramp-up of new channels can be accomplished with minimal effort. This can require new investments in technology, including the development of modular IT systems.

Digital and Analytics Capabilities. Closely tied to the establishment of an omnichannel customer experience is the development of sophisticated digital and analytics capabilities. This will likely necessitate considerable investment.

Done well, however, it will allow the incumbent to have a full, 360-degree view of the customer. Such an understanding, encompassing essentially all relevant information about the customer and his or her relationship with the utility (including power usage data, previous service calls, preferred channels of communication, and changes in billing and payments), will allow the company to provide a truly superior level of customer service, one that promotes both customer retention and the chance that customers will provide spontaneous, word-of-mouth marketing for the utility.

In fact, the development of cutting-edge IT capabilities should be a critical element of an incumbent’s battle plan in the face of liberalization. An ideal IT environment will be cloud-based and utilize machine learning and as much automation as possible in support of the company’s core operations, complemented by robust application program interfaces. The IT function should also provide dashboards with relevant information for each manager and department.

New Products and Services. The launch and offer of new products and services can help lock in current customers. It can also increase their spending with the company and open up entirely new avenues of revenue. Offerings that might appeal to residential customers include the installation and maintenance of solar panels (Australia’s AGL Energy, for instance, offers to install a solar system for $0 down), energy-efficiency-related products and services, setup of at-home electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and installation and maintenance of HVAC-related products. Spanish utility Naturgy, for example, offered residential customers maintenance services for their power and gas systems even before full liberalization occurred.

Establishing a second brand can also be an effective weapon for an incumbent in the campaign against new, low-price competitors. Done well, this can be particularly effective, combining the cost benefits of a lean operating structure with the incumbent’s scale advantages.

Incumbents’ need to improve their game in the face of liberalization will be intensified by ongoing advances in customer service in other industries. These advances, typically driven by digitization, are steadily raising customers’ expectations (in both the B2B and B2C segments) of what is possible and, increasingly, customary. Expected standards for incumbent energy companies will continue to rise in parallel.

Ultimately, incumbents facing market liberalization have two choices. They can sit idly and lament what the market’s opening may do to their business. Or they can make bold moves that defend, to the degree possible, the company’s current business and position the company to seize potentially lucrative opportunities in the future. Which will you choose?