Family businesses play a significant role in driving economic growth, contributing between 25% and 49% of GDP in countries as diverse as India and Germany and employing millions of people. Their importance as commercial enterprises does not change their essential character. At their core, they remain families, a fact that has implications for how these businesses are managed. All families are different, but each has a common bloodline. And even as bloodlines thin, their underlying nature often prevails.

Managing a family business is complex. In addition to managing the business, the family needs to manage itself. In other types of commercial organizations, regulatory structures, rules, and roles are firmly in place. Similar guardrails and guidance do not exist for families. At a minimum, the family needs a mechanism for aligning the views of its members and communicating those views to management. As the size of the family grows, alignment becomes much harder to achieve without guidelines and processes.

In its ideal form, a family is about love, affection, fairness, respect, and trust. And yet every family member understands that frustrations and fights can arise. In interviewing the members of 25 family businesses, we found that seemingly trivial issues can lead to major eruptions. People get hurt. They stop talking to one another, let alone working together.

Conflicts arising from hurt feelings are rarely about right and wrong. Usually they can’t even be reduced to material issues like money or other matters of self-interest. Those “hard” issues are easier to identify and resolve rationally. In contrast, our interviews revealed that conflicts often spring from a well of “soft” issues. Once the resulting injury occurs, it is difficult to heal. Dislike, distrust, and disrespect take hold. Family ties are often irreparably damaged.

The importance of soft issues in the context of family businesses is often misunderstood but cannot be overstated. The fact that so many conflicts originate in soft issues tends to be overlooked, because it is difficult for nonfamily members, external observers, and advisors to detect, let alone solve, these problems.

Families have created governance structures, such as family assemblies, family councils, and family charters, for managing critical business issues around succession, distribution of dividends, and management. They need an analogous framework and processes to address the more subterranean soft issues that do not get the attention they deserve.

Soft Issues and Soft Rules

Soft issues are anchored in emotions, such as hurt feelings or anger. Their cause is immaterial. Nor does it matter who is right and who is wrong and whether the pain was inflicted deliberately or inadvertently. All that matters is that someone’s feelings were hurt.

Every family has a set of “soft rules,” or conventions, which may or may not be explicit, governing the behavior of its members. When these are violated, people get upset. Soft rules are a set of expectations regarding how members of the family interact with and influence one another. For example, one rule might be that no family member should ever be compared publicly with another family member. Another might be that family members may not talk about the family to the media.

Soft rules have three key characteristics. First, they are based on emotions and values such as affection, fairness, respect, and equitable treatment of family members. Second, they vary across families and are shaped by the norms and conventions of both the family and the larger society. These norms evolve over the generations; what is acceptable now may be challenged later. Finally, when a soft rule is violated and someone’s feelings get hurt, discord and conflict can develop if the issue is left unaddressed. A basic feature of a family business is that its members cannot opt out as easily as a company employee can. This increases the risk that problems will fester.

Families need to manage their soft rules. This is always the case, but it may be less apparent in the first two generations of ownership, when the family is relatively small. As the family grows and matures, the need becomes pressing. It is therefore prudent (and easier) to put the necessary structures in place as early as possible.

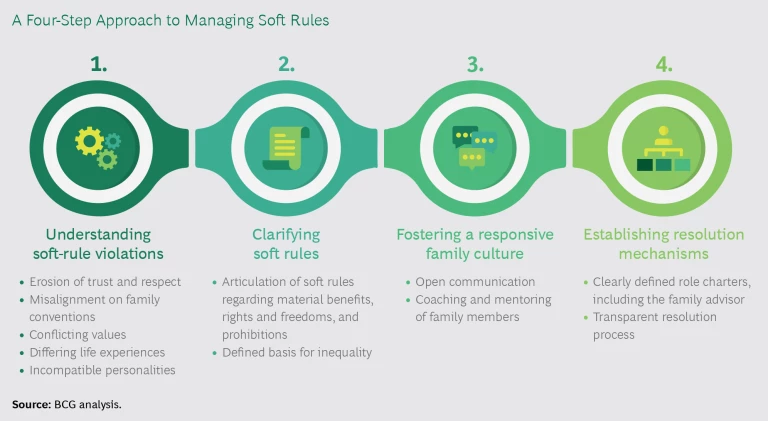

A four-step approach can give families the understanding and tools they require to manage their soft rules effectively. First, they must understand why soft-rule violations occur. Second, they much clarify and explicitly articulate their soft rules. Third, they must foster an open and responsive family culture. Finally, they must establish transparent and fair resolution mechanisms. (See the exhibit.)

Understanding Soft-Rule Violations

Since soft issues arise out of emotions, they manifest in different ways. Introverted family members may rarely speak out until their feelings bubble over and erupt. Others may cause incalculable damage through their constant volatility. Recognizing these emotions is the first step in preserving a family’s soft rules and managing the conflicts that violations can engender.

Soft rules are generally understood by all family members, though they may not be equally appreciated because they are implicit. The founding members and earlier generations of a family may have internalized these rules, but later generations may not understand or accept them in the same way. Some members may find the soft rules unfair, constraining, or irrational, but may be reluctant to talk openly about the traditions and values that underlie them. Not surprisingly, a family’s soft rules are often breached in stealth rather than in the open.

There are five sources of discord around soft rules—erosion of trust and respect, misalignment on family conventions, conflicting values, differing life experiences, and incompatible personalities—and family leaders need sagacity and stewardship to navigate them. Awareness of why violations occur is a critical part of managing soft rules, enabling the timely identification and resolution of problems. Once the reasons for violations are understood, families can clearly articulate their soft rules and communicate them more broadly.

Every family has a set of “soft rules,” or conventions, which may or may not be explicit, governing the behavior of its members.

Erosion of Trust and Respect. This typically occurs when a powerful family member makes decisions that others view as biased, unjust, or unethical, or when he or she is felt to be unfairly critical of or deferential toward a particular member of the family. Erosion of trust can also arise if the rules seem to be applied unequally or if decisions are not made in the common interest. Left unaddressed, these problems tend to grow over time.

Misalignment on Family Conventions. Family members are expected to abide by deep-rooted family conventions, but people of different generations, and sometimes even people within the same generation, may have a problem with them. Fairness is often in the eye of the beholder. Tensions can surface when some family members believe that norms around age, gender, or nonblood relatives are out of step with the times. For instance, the exclusion of women from participation in the business may no longer be acceptable. Similar conventions regarding in-laws, adopted children, and children from a previous marriage can likewise cause resentments.

Conflicting Values. Values are inculcated in family members at an early age and are reinforced by various influences, including religion and the stories that families share. However, as family members grow apart—because they live at a distance from one another, for instance, or travel in different social circles—these values become harder to maintain, and disagreements can arise. For example: Who receives recognition for hard work and business acumen, the family as a whole or an individual family member? Are positions in the hierarchy awarded based on merit, age, or lineage? Some family members may prioritize excellence in the quality of the service or products that the company sells, while others may be more focused on growth. Some may value profits over social responsibility and humane working conditions, or vice versa. Such disagreements may even extend to an individual family member’s personal life, such as the appropriate amount of spending money or whether a local or an overseas education is preferable. Unless these issues are openly discussed, members will not understand one another’s viewpoints.

Differing Life Experiences. Family members may inadvertently violate a family’s soft rules because of their life experiences. Children may be sent away to school and families may disperse to different locations within the country or around world, exposing their members to new influences. Marriage and travel for work or pleasure can likewise cause family members to have different views from those of the rest of the family, leading to tensions both within and across generations.

Incompatible Personalities. Personality conflicts often arise in the management of a business. Some family members may be analytical, while others may operate on their gut and make quick decisions without discussion, let alone consensus. Unless these differences are recognized and appreciated, friction and grudges can fester. Personality tests such as the Myers-Briggs assessment can help flag incompatible personality types and form the basis for coaching, counseling, and mentoring.

Clarifying the Soft Rules

Because the line between family affairs and business affairs is blurry, explicitly articulating a family’s soft rules is essential to avoiding conflict. It’s not always easy to get family members to recognize the importance of laying out those rules. But unless everyone understands and is willing to abide by them, behavior that leads to violations will continue. There must also be consequences for violating the rules, and these must be clearly communicated and understood.

Articulation of the Rules. Families need a loose charter that clarifies both the obvious and the more subtle aspects of its soft rules. Some of these are easier to identify, manage, and enforce than others.

- Material Benefits. Compensation, company benefits, and use of the family’s real estate and other assets need to be clearly laid out. Even smaller items, such as cars, chauffeurs, travel expenses, club memberships, and domestic help can be sources of conflict. Responsibility for the costs of health care and education should also be made explicit.

- Rights and Freedoms. It’s much trickier to articulate and reach agreement on these matters. When can a family member enter the family business? Does he or she have the freedom to pursue business interests outside the business? Marriage—both its timing and the freedom to choose a partner—is an especially fraught issue in some societies. Other rights and freedoms include the ability to lead a public life in the media, serve on external boards of directors, and run for public office.

- Prohibitions. Some of these are matters of common sense and common courtesy: family members may not misuse family funds, talk to the media about family affairs (or, even worse, seek redress in court), or be verbally or otherwise abusive to one another. Many families also have more subtle prohibitions, against excluding or ostracizing a member or branch of the family, for example, or violating cultural taboos, such as speaking back to an elder in public. Families can draw up comprehensive lists of prohibited behaviors with examples, and although these will never capture all possible violations of family norms, they can sensitize people to potential sources of conflict. Unless specified otherwise, all family members must be held to the same standard and receive the same penalty for violations.

When Inequality Is OK. Culture or tradition is often the basis for inequality among family members. The head of the family, for example, may be allowed to raise his or her voice or speak in ways forbidden to others. These traditions need to be well understood. It should not be assumed that younger family members will simply accept that not everyone is treated equally regarding material benefits, rights and freedoms, and prohibitions.

Because the line between family affairs and business affairs is blurry, explicitly articulating a family’s soft rules is essential to avoiding conflict.

Unequal treatment within families often springs from gender, primogeniture and other generational factors, or a particular individual’s financial assets, contribution to the business (in terms of time, for instance), business interests outside the family business, or public persona. None of these is set in stone and may change over time. But when a family’s underlying dynamics change—because of female family members challenging gender as a justification for inequality, for example—that should be reflected in its soft rules.

Fostering a Responsive Family Culture

To manage soft issues, families need to create a culture of open communication and responsibility. When family members are unable to voice their frustrations and when those who cause offense are not expected to make amends, violations of soft rules will occur and worsen. To preserve harmony, family leaders need to be aware of the risks of ignoring these issues.

Open Communication. Leaders need to make family members feel comfortable raising uncomfortable issues. Speaking up should be viewed not as a disruption but as a constructive effort on behalf of the family. No topic should be trivialized or considered too insignificant to address.

The head of the family has an outsized role in establishing this culture. Explaining decisions and addressing concerns directly can go a long way toward ensuring that small problems do not become big ones. The family’s leader—or a governance body such as a family council—can facilitate open discussion through strong and clear messaging. Leaders can also model the desired behavior by encouraging candid discussions about the family’s soft rules. They should be sensitive to the way shifts in societal norms, such as female participation in the economy, may affect the family.

For families that are framing their soft rules explicitly for the first time, the involvement of the entire family in open discussions can help break the ice. Informal mentoring and coaching sessions (not necessarily led by family members) can make speaking up feel more acceptable. Any family member who notices a violation of a soft rule should be encouraged to bring it to the family’s attention, not just the individual who was affected by it.

One delicate issue is a soft-rule violation by a senior family member, especially the head of the family, that is brought to the family’s attention by a younger family member. Culture and tradition may not easily accommodate the discussion required to address the issue. Fear of retribution, real or perceived, can have the same effect. A mechanism is therefore required to ensure discretion and prevent the discussion from going beyond the forum provided for violation management.

Multigenerational family businesses can benefit from discussion forums comprising representatives from each generation tasked with encouraging candid conversations within and across generations. Families that have a de facto “chief emotional officer” (usually the matriarch) can gradually nurture the culture of openness. It is essential for families to establish this culture before any soft-rule violations occur—even as early as the second generation.

Culture of Responsibility. When a soft rule is violated, a quick and sincere apology can often resolve the issue. This is easier said than done, especially when the violation is unintentional and the individual responsible is unaware of its consequences. All family members must have the emotional sensitivity to recognize the need for an authentic apology and the humility required to offer one. This is much more likely when family elders serve as role models.

To manage soft issues, families need to create a culture of open communication and responsibility.

As a first step, the family should cultivate emotional intelligence and sensitivity through coaching and counseling by outside parties or respected senior family members. An emotional-intelligence module can be incorporated into leadership readiness and performance coaching programs and made a priority in development plans for family members. Families that elevate the importance of emotional intelligence and other soft issues will empower their members to address them constructively.

Emotional intelligence is a precursor to taking the responsibility needed to apologize. In families whose senior leaders are unaccustomed to admitting errors and shortcomings, apologizing will likely feel uncomfortable. For a culture of responsibility to take hold, it needs to be woven into the family’s fabric and reinforced by the head of the family and other senior leaders. When people see the family’s leaders apologizing, the needed culture change will occur more swiftly. This is especially true for families in which apology has been stigmatized.

Not all apologies need to be made publicly. A private apology or acknowledgment of a mistake will often go a long way to changing the family culture. All family members must understand, however, that this cultural shift will take time to take hold. In the interim, family members must learn not to harbor grudges.

Establishing Resolution Mechanisms

Once a family’s soft rules have been articulated and a culture of addressing violations established, a means of dealing with unresolved issues is still needed. This mechanism should be clearly defined and aim to bring harmony when informal discussions and apologies have not been sufficient. The effort can be led by the head of the family or, more likely, by a family governance body or an individual supported by the head. The approach chosen depends on the nature of the family but should always involve respected family advisors and transparent processes.

Family Advisors. A family council or other governance body can play a major role in the resolution management process, but the participation of a family advisor is likely to be beneficial. The advisor can be a family member, a friend, or an outside professional who has the support and confidence of the head of the family and of the members of each generation within it. In some families, it may be helpful to have both an internal and an external advisor. Either way, he or she should be respected, trustworthy, and approachable. Above all, the advisor should understand the family’s dynamics and traditions and be capable of both discretion and impartiality.

The family advisor should be the first point of contact for anyone who feels that a soft-rule violation has occurred. The advisor then assesses the situation and, if the family member’s concerns seem valid, orchestrates discussions with senior family members and explores a means of informal resolution. The advisor may also recommend that a family governance body take up the issue or delegate resolution to an individual under his or her supervision.

The family advisor may want to bring in external specialists to offer an independent assessment and provide counseling and coaching to family members. This kind of support is uncommon in many families but can be invaluable.

Transparent Processes. Any resolution process depends on transparency for legitimacy, especially for those involved in a dispute. Transparency needs to be built into the design of the process and into decision making. The assessment made by the family advisor and governance body must be made available to all parties, who should have the opportunity to respond within the framework of the family’s soft rules.

For a culture of responsibility to take hold, it needs to be woven into the family’s fabric and reinforced by the head of the family and other senior leaders.

Regardless of the type of enforcement mechanisms that a family puts in place, it is important to recognize that the essence of soft rules is that they are soft. Minor violations should be addressed through family counseling and mentorship, and more serious violations by the family’s expression of disapproval and reproof. The power and efficacy of disapproval can go a long way in reinforcing soft rules. Harsher penalties, such as exclusion from the business, should be a last resort. When overused, these can fray family unity and, even worse, lead to the family’s breakup.

In many cases, just having a chance to voice a concern can be as effective as punishment in preventing an ongoing soft-rule violation. At other times, some form of censure is needed to satisfy a wronged family member. But ideally, families can resolve issues early so they do not fester and turn septic.

When families are owner-managers of a business, managing the family is often harder than managing the business. To function well, families must deal with the hard issues that cause disputes. But they must also understand the importance of soft issues, which likewise require structure, process, and good decision making to be addressed effectively. For family businesses, managing soft rules can unlock the latent energy that has been bottled up because of unresolved emotional problems that may be slowly undermining the business. Glossing over soft issues almost always leads to hard problems.