With the pandemic-induced collapse in oil prices sharply reducing free cash flows, international oil company (IOC) leaders must think even harder about where they allocate scarce capital. Even before the crisis, these companies were already grappling with the seemingly opposing goals of expanding into low-carbon growth areas, such as renewables, or sticking to traditional dividend payouts funded through reinvestment in their core businesses. In the current environment, then, increasing total shareholder returns (TSR)—share price changes plus dividends reinvested—will likely be a true test of leaders’ strategic vision.

We believe an effective solution will start with IOCs fundamentally transforming their upstream businesses so that they deliver stronger returns, irrespective of oil price movements. Until now, oil and gas companies’ efforts to transform upstream returns have had mixed results. But with a more ambitious, less incremental approach that improves risk management and capital allocation processes, leverages core capabilities, and uses standardization to drive down costs, companies can generate more free cash. They can then use that cash on a wide range of value creation drivers, including growth initiatives.

Upstream Returns Have Fallen, Even at the Same Oil Price

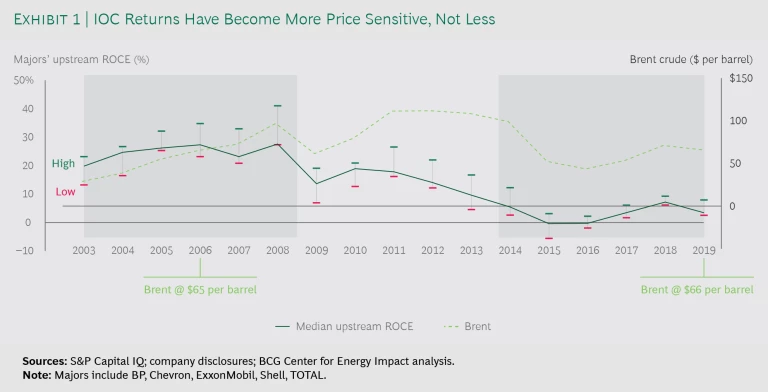

Weak upstream returns are a growing problem for IOCs. Between 2014 (when the last oil price crash occurred) and 2019, the Majors, the five largest publicly listed IOCs, spent roughly $615 billion—about 85% of total capital employed—on their upstream businesses. Yet, despite the huge sums, returns on capital employed (ROCE) from these businesses have steadily fallen for more than a decade. For oil prices, 2006 and 2019 were similar, with the average Brent crude price hovering around $65 per barrel. But upstream returns for the Majors were starkly different: in 2006, median upstream ROCE was above 27%, while in 2019 it was just 3.5%. (See Exhibit 1.)

Industry investment decisions play out over decades, and oil price levels can have a material impact in any given year. Arguably, the 2006 figure partly reflects a rapid surge in prices post-2004 and reduced capital expenditure levels in the previous decade. The difference in returns, however, is striking.

Industry investment decisions play out over decades, and oil price levels can have a material impact in any given year.

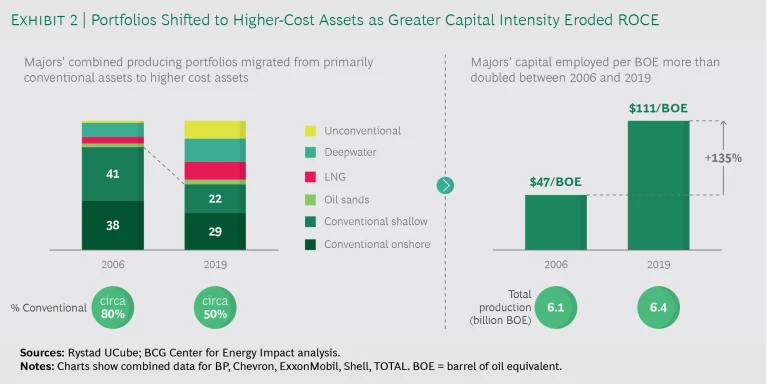

One reason for the disparity: changes in portfolio composition. Since the 1970s, resource-owning national oil companies have steadily reduced IOCs’ access to cheap, readily available barrels offering good returns. By 2006, more than 80% of the Majors’ producing portfolios were still made up of conventional assets (onshore and shallow water assets with productive reservoirs and amenable contract terms), providing proven, attractive returns more or less across commodity price cycles. Today, conventional assets comprise less than half of the Majors’ portfolios, with many of them earmarked for divestiture because of their dwindling contribution to companies’ production and reserves.

To grow their production and earnings, the Majors spent more than $1 trillion on capital expenditures from 2005 to 2014, reconfiguring their portfolios so that they included a bigger share of higher cost, more technically challenging (and often higher carbon) assets in new areas such as global deepwater drilling, US unconventional oil and gas development, oil sands, and liquefied natural gas. Indeed, their aggressive spending in these areas continues to weigh on investor perceptions of oil and gas companies as effective capital stewards.

The challenges of producing oil and gas in these areas significantly increased companies’ capital intensity and put further pressure on upstream returns. Between 2006 and 2019, the Majors’ average capital employed per barrel of oil equivalent more than doubled, from $47 to $111. (See Exhibit 2.) These returns were also more vulnerable to being eaten up by oil price falls.

Cost Initiatives Have Fallen Short

The portfolios of the IOCs today still reflect investments driven by a different and earlier set of industry assumptions. Companies in the past took the view that, due to long-term supply constraints, the cost of oil and gas would remain high and any price declines would be temporary. They assumed that high extraction costs would be absorbed by high overall price levels. But while this view no longer holds, and oil and gas companies have recently reworked their long-term oil price assumptions downward, they have yet to truly fix their high costs.

Even though oil and gas companies have recently reworked their long-term oil price assumptions downward, they have yet to truly fix their high costs.

IOCs have made concerted efforts to address their upstream cost issues in recent years, but they have not gone far enough. With the sharp fall in the oil price from 2014 to 2015, companies revisited their strategy of spending big on high-cost resource plays. The result was greater diversity in their upstream strategies and portfolios. To reduce capital expenditure, companies refocused their efforts on areas where they had a competitive advantage and could deliver greater productivity at lower cost.

For example, IOCs have redesigned their portfolios around particular regions, types of asset, the level of country risk, and opportunities for value chain integration. But while the industry rethink has improved its efficiency and lowered the average breakeven prices in portfolios to around $45 per barrel (excluding dividends), the sector’s profitability continues to depend on structurally high oil prices compared with the price levels likely in the coming decade.

Where Oil Companies Need to Go

The IOC business model traditionally combines lower growth, relative to other industry sectors, with higher returns. Today, however, IOCs’ upstream ROCE lags some of the larger exploration and production companies, indicating that IOCs are missing a trick. Improving upstream returns is no easy task, but we believe IOCs are significantly underplaying the potential value they can unlock.

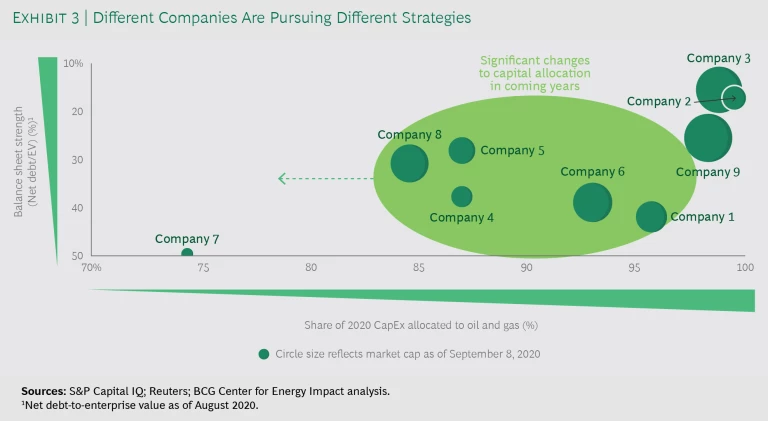

Partly this is because decisions today about where to allocate capital are being considered in near-existential terms. Some IOCs, mainly European, have responded to the emergence of a low-carbon world , and the possibility that global oil demand may have already peaked, with a redirection of capital into low-carbon energy markets. (See Exhibit 3.) Many of these companies, however, continue to rely on their upstream businesses to fund these investments and drive shareholder returns. They are setting ambitious ROCE targets so that they can finance expansion into renewables, bioenergy, and e-mobility.

In contrast, US IOCs, by and large, are concentrating on their core operations in oil and gas. But while they are investing in upstream assets, such as shale oil and gas, there are limits to how far they can access lower-cost production or restructure their portfolios to optimize in areas that offer higher returns. For these companies, maintaining generous dividend payments remains an imperative equal to, if not greater than, investing in new oil and gas fields.

Improving the profitability of upstream businesses gives IOCs more cash to deploy.

As a result, companies are basing their capital allocation decisions either on their strategic objective to diversify outside oil and gas or on the need to maintain payout levels while reinvesting in their core businesses. But this ignores the reality that improving the profitability of upstream businesses gives IOCs more cash to deploy. Such cash that could go toward a wide range of value creation levers that underpin successful TSR performance and an increasing valuation multiple, including earnings growth, debt reduction, and a stable or growing payout.

To achieve double-digit upstream ROCE regardless of oil prices and reduce capital employed per barrel, companies need to significantly transform their upstream businesses. Limited access to cheap barrels means that companies can’t simply rip up strategies forged over decades and start from scratch. Instead, they need to refocus their portfolios on lower-cost, lower-emission barrels where they can, while simultaneously introducing measures to cut costs and reduce capital intensity.

We believe that IOCs that become upstream leaders will have forged strong positions in the following areas.

Risk Evaluation and Management. The oil and gas industry is a risk management business. Success is closely linked to companies’ ability to evaluate and manage risks across their portfolios. Worsening upstream returns over the past two decades are arguably due to shortcomings in the sector’s assessment of risk. Yet there are standout examples of companies skillfully managing risk, leading them to outperform their peers. Upstream leaders will apply best practice in risk management and future proof their portfolios in readiness for an evolving energy landscape.

There are standout examples of companies skillfully managing risk, leading them to outperform their peers.

Governance Around Capital Allocation Decisions. Weak industry returns are a clear indicator that oil and gas companies have at times made poor investment decisions. Having rigorous capital allocation processes in place that contain effective checks and balances will ensure that only projects with a balanced risk profile move forward. As companies expand into new low-carbon areas, they will need to assess the future returns and cash flows from a range of investments with very different characteristics while achieving their overall investment objectives. The key lies in a systematic but nimble approach for allocating capital.

Core Capabilities and Standardization. Upstream leaders will focus on leveraging areas of strength that have the potential to deliver superior returns. For example, they will prioritize regions where they can secure better contract terms than competitors, or where they can bring company-specific technical expertise to bear. At the same time, they will introduce more standardized processes that can drive down costs and improve cash flows across their operations. And they will take a less incremental, more fundamental approach to ensure their cost reduction efforts are successful.

Measuring Success with TSR Performance. The true measure of success for a company is the improvement in its total shareholder return performance. Earnings growth, an increase in the valuation multiple, and a stable and growing payout are all vital levers for achieving better TSR. To optimize these levers, upstream leaders will cut costs and transform their u upstream operations so that they can flourish at lower oil price levels. They will also be responsive to concerns from all their stakeholders, thereby achieving superior returns.

IOCs’ upstream returns have shrunk dramatically in recent decades. But their efforts to reverse this situation have not gone far enough and have failed to deliver healthy ROCE. Companies need to adopt a more ambitious approach if they are to transform their upstream operations. By doing so, they can generate cash for a wide range of value creation levers.

In a forthcoming article, we will examine in detail the structural transformation measures that will be required from oil and gas companies.