While Canadians often believe that our country is a model when it comes to inclusion, the hard truth is we have a long way to go toward achieving equity for the Black population in Canada. A new review and compilation of the available data by BCG and CivicAction demonstrate the depth and pervasiveness of anti-Black racism in Canada, and how systemic racism against Black individuals appears across their full lifecycle in areas like education, employment, healthcare, and policing.

“With all that’s happened in the world - from the killing of George Floyd to how COVID-19 has disproportionally impacted those from racialized communities - we needed to act,” says Leslie Woo, CEO of CivicAction. “This report lays bare the depth of anti-Black racism in Canada. We are calling on Canadian companies, governments, and individuals to deepen their commitment and accountability to addressing anti-Black racism.”

The authors compiled data and consulted with a subset of leaders and experts from Black communities in Canada. We took a cross-Canada lens, using national data where available, with a focus on the Greater Toronto Region where more specific data was tracked and available. We then examined proven actions and promising practices from around the world to identify interventions that could be considered for adaption here at home. Our goal is to underscore the systemic oppression that Black people in Canada face – with the aim to enable a better understanding, to illustrate the importance of action, and to sustain motivation and momentum for change.

Data indicates that anti-Black racism exists in Canada and is worse than many Canadians think

The research we compiled shows the realities of the Black experience in Canada, which when put together are eye-opening:

- Black students are four times more likely to be expelled from a Toronto high school than White students

- Black workers are twice as likely as Asian workers and four times as likely as White workers to report experiencing racial discrimination in major decisions at workplaces in Canada

- Black university graduates earn only 80 cents for every dollar earned by White university graduates – despite having the same credentials

- Black women are three times less likely to have a family doctor than non-racialized women in Ontario

- Black residents are 20 times more likely than a White resident to be shot dead by police in Toronto

At the same time, a 2019 survey indicates nearly half of Canadians believe discrimination against Black people is “no longer a problem” – even as 83% of Black people in Canada say they are treated unfairly at least some of the time.

The events of 2020, including the death of George Floyd, have drawn global attention to the reality of systemic anti-Black racism. Now more than ever there is a need to double down on efforts to eliminate anti-Black racism in Canada. The data and insights in this report should serve to catalyze continued action by individuals, corporations and governments in Canada

The state of anti-Black racism in Canada

Black communities in Canada have doubled in size over the past 25 years to more than 1.2 million people – 3.5% of the national population. Even though more than one out of every 30 Canadians is Black – a number that jumps to one in 11 people in Toronto – the experiences and diversity of Black communities in Canada are often aggregated into the category of “visible minority” and overlooked.

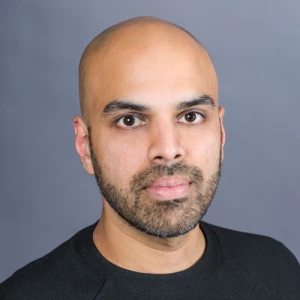

To help paint the picture, we have compiled a data set that highlights some of the specifics of Canadian Black communities' experiences. We focused on a set of specific lifecyle areas where Black Canadians experience racism, guided by four of the pillars of the City of Toronto’s Action Plan to Confront Anti-Black Racism, and in areas where at least some existing data had been published. Our goal in synthesizing this data is to provide Canadians with a mirror reflecting the disparate outcomes in our country, in order to drive education and inspire sustained action.

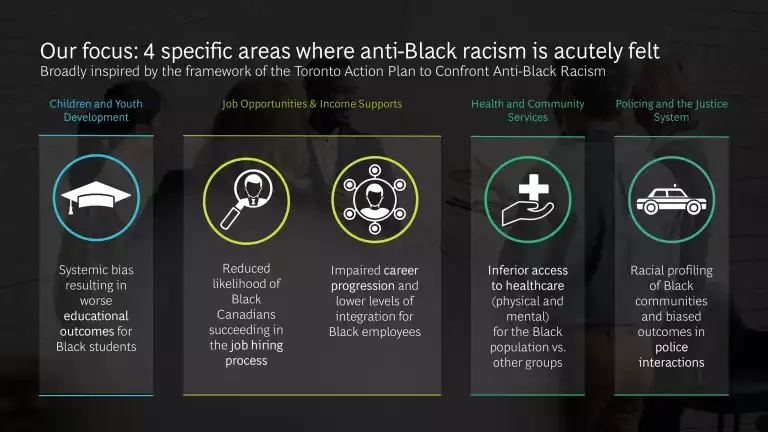

Children and Youth Development. While education is a bedrock foundation for human development, Black students in Ontario have appreciably worse education outcomes. In Toronto, the dropout rate for Black students is 23%, compared to 12% for White students. Facing systemic biases day to day, Black students also achieve lower EQAO (Education Quality and Accountability Office) test scores in mathematics, reading, and writing.

Why is this the case? We have identified data showing the multiple ways in which systemic racism in Canada drives worse educational performance for Black students.

One challenge for Black students is the lack of Black teachers in the classroom. Recent studies show that having a Black teacher can result in a 13% increase in enrolment in post-secondary schooling and decrease the probability of dropping out by 29%. Yet, while Black people make up 3.5% of Canada’s population, only 1.8% of teachers are Black.

This lack of Black representation makes a difference in multiple ways. For one, Black teachers are less likely to use language in the classroom that negatively labels Black students.

“Teachers might use language to describe Black children that they would not for White children, such as ‘threatening,’” according to one Black leader we consulted. “From an early age, kids are being told who they are, from the people that they spend the most amount of time with [their teachers]. Who teachers think you are and what you can be is really important.”

Another impact of implicit bias from teachers is seen in assessments of student capabilities. For example, only 3% of those labeled “gifted” in Toronto schools are Black, despite Black students making up 12% of the population. A study found that teachers in Ontario were twice as likely to rate a White student as “excellent” than a Black student on their report card – even when those students had the same standardized EQAO scores. Meanwhile, Black students are 2.5 times more likely than White students to be streamed into non-academic “applied” programs in Toronto – in turn affecting everything from graduation rates to post-secondary prospects.

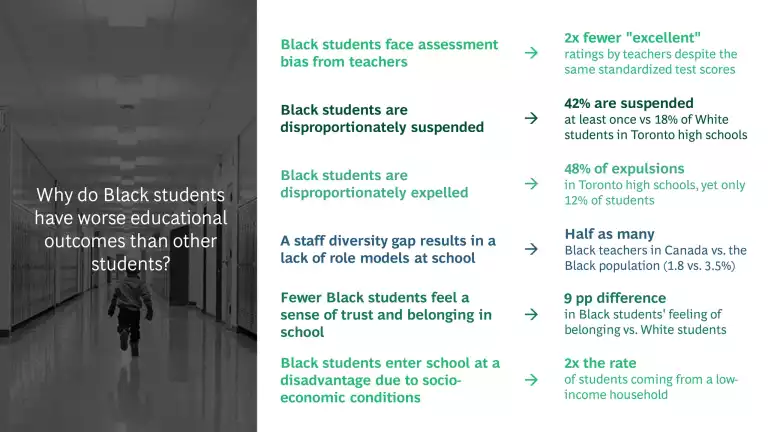

Job Opportunities and Income Supports. Racism in the workforce creates barriers to employment and impairs career progression for Black people. One stark statistic – as of October 2020, the unemployment rate for Black Canadians was 5 points higher than the rate for Canadians who are not a visible minority (11.7% vs. 6.7%). And while the impact of COVID-19 has driven up the unemployment rate for all Canadians compared to October 2019, the Black unemployment rate was 3.8 points higher, while the rate for non-visible minorities was up just 2.6 points. This is in part because Black workers are disproportionately represented in service industries, which are particularly affected by COVID-19. With a second wave and subsequent lockdowns now upon us, the Black unemployment rate may be primed to rise further.

What drives these higher unemployment figures? Black people in Canada face many systemic challenges and barriers in the hiring process. Even when experience is comparable to that of non-Black candidates, systemic biases make it more difficult for Black candidates to land positions for which they are qualified.

One particularly sobering study showed the extent of this bias. The study, conducted in Toronto, used the same resume and cover letter, with only two differences: whether the applicant had a White-sounding or Black-sounding name, and whether the applicant referred to having a criminal record in the cover letter.

The results showed that among those with no criminal record, the “White” resume received three times the number of call-backs as the “Black” resume. When both candidates indicated a criminal record, the difference in call-backs jumped to 12x. And perhaps most shockingly – the “White” applicants with a criminal record still got nearly twice as many calls back as the “Black” applicants with no record.

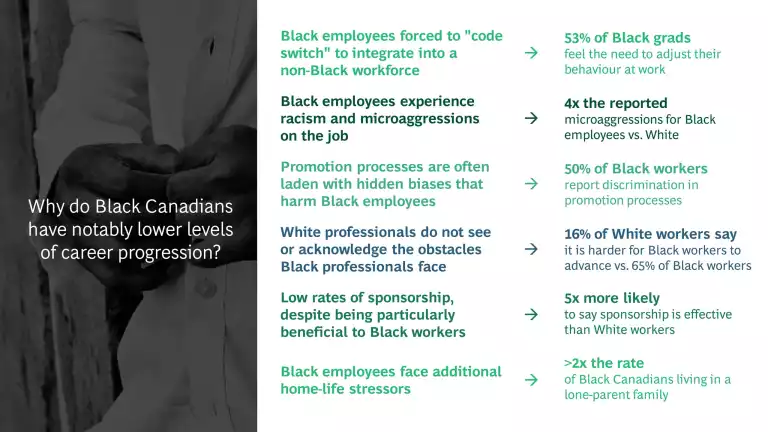

When Black people do succeed in finding a job, systemic racism in the workplace can result in hitting up against a glass ceiling. In addition to facing microaggressions and having to “code switch” (defined as a person changing the way they express themselves when they are around non-racialized people in the workplace), Black employees have low rates of sponsorship and find hidden biases in promotion processes. This is reflected in the data that shows Black leaders hold less than 1% of executive roles and board seats at major Canadian companies.

One specific challenge we heard referenced continually through our interviews was that Black employees experience microaggressions on the job. Microaggressions are brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages – anything from stereotyping comments to racially insensitive language. These microaggressions often demean Black workers, instill distrust, and prevent a sense of belonging.

As just one example, a Black early executive at a Canadian bank relayed the following story: “I was at a breakfast with a senior executive – we spoke for about 15 minutes, and it was great small talk. Two days later, I was running a meeting to which the executive was invited. As I approached to greet him, another White colleague walked in from a different direction. As soon as he saw this person, he started calling her name -- and then stuck out his arm to give me his coat to put away. While he probably didn't see who I was, he assumed that I was someone to whom he should pass his coat – he didn't think to check.”

These microaggressions and the need to “code switch” take an emotional toll on Black employees. Survey data indicates that Black workers are less satisfied at their jobs and are 50% more likely to be planning to leave their job than White workers.

The impact of systemic anti-Black racism driving employees away doesn’t just impact those workers – it also results in a financial hit for businesses, as the average cost of replacing an employee is 33% of their annual salary.

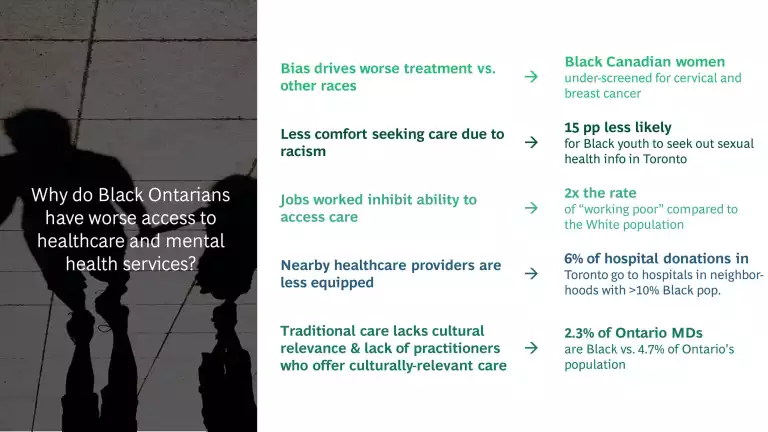

Health and Community Services. A lack of access to health care in Black communities leads to worse physical and mental health outcomes for Black people in Canada compared to other groups.

Although tracking of disparate health impacts is limited in Canada, the data we do have shows notable differences for the Black population – especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. In one national survey, 21% of Black Canadians said they knew someone who had died of COVID-19, vs. 8% of non-Black Canadians. And in Ontario, COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on the most heavily racialized areas. Highly diverse neighbourhoods – where more than 10% of the population is Black – have four times the age-adjusted COVID-19 hospitalization rate and twice the death rate of the least racialized neighbourhoods (where just 0.5% of the population is Black).

But the challenge extends well beyond COVID. Data from Ontario shows certain health conditions are much more prevalent in the Black population. For example, Black women in the province have three times the rate of diabetes and 1.7 times the rate of hypertension of White women in the province.

What drives these worse health outcomes? In part it is because many Black communities have impaired access to care, connected to systemic racism in Canada. This includes everything from worse-equipped hospitals in Black neighborhoods in Toronto, to less-flexible jobs that make seeking care a challenge, to fear of racism from providers when seeking out care.

One challenge in accessing health care for Black patients is the lack of culturally appropriate care. This is caused in part by Black doctors being noticeably underrepresented in care settings – there are 50% fewer Black doctors than the Black share of the population in Ontario. It also manifests in a lack of training for non-racialized practitioners about the Black population. “My mother wouldn’t get help because she couldn’t describe her pain in her own words, and the doctor did not understand the nuances of what pain looks like in our culture,” one Black community leader told us.

This is especially true of the mental health system, which is not well-positioned to deliver care to Black communities. Experts noted to us that the mental health system does not have culturally adapted therapies targeted to Black recipients and fails to do the outreach required to reduce barriers to access and stigma. This results in the Black population being four times less likely to access mental health services than the non-racialized population.

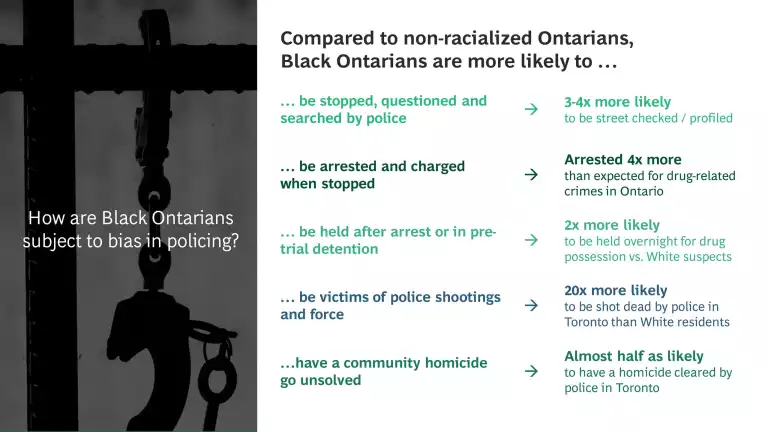

Police Services. Police bias against Black people has been a focal point of protests in the US in recent months – and our review of the data indicates there are stark differences in outcomes of police interactions with Black residents in Canada as well.

Only a quarter of Black people in Toronto trust police to treat them fairly compared to three-quarters of White people. This is not surprising, when we consider that Black people are significantly more likely to be profiled, arrested, held overnight, and be subjected to police force than non-racialized Ontarians.

The statistics on disparities in police use of force apply across all types of police interactions. According to an Ontario Human Rights Commission report, although Black people make up 9% of Toronto’s population, they represent:

- 36% of cases where police used pepper spray on an individual

- 46% of cases where police used a Taser on an individual

- And 57% of cases involving a police dog

Most disturbingly – Black Torontonians represent 70% of civilian deaths in police shootings, meaning the police are 20 times more likely to kill a Black person than a White person.

This reality of police bias takes its toll – among Black Ontarians subject to bias-driven street checks, three quarters reported a decreased sense of belonging in society, and 60% reported negative mental health effects.

We can drive change through system-level interventions

Anti-Black racism in Canada negatively impacts the nation’s social and economic fabric, reducing the potential of over a million Canadians. We must work together to achieve system-level change through interventions that address racism across all life cycle areas.

There is no single solution that can undo hundreds of years of racism, and solutions will need to come from a wide range of places, organizations and individuals. As part of this work, we scanned and compiled examples of promising practices that could make up the quilt of solutions required to start to change the experience of Black individuals in Canada.

Below is a summary of the identified examples – followed by a deeper dive in selected areas. We have brought forward these ideas because there is proof that they work – in other locations, or for other disadvantaged groups. Applying them broadly in Canada can help reduce many of the barriers that our Black communities face today.

In addition, a key place to start would be to obtain more data and track key metrics. Compared to the United States, Canada collects very little data by race and ethnicity. Tracking outcomes for Black people in Canada, such as university admission rates, home ownership rates, and infant/maternal mortality rates – all data regularly tracked by US governmental agencies – would enable us to more clearly identify and intervene against the primary barriers impacting Canada’s Black population.

IMPROVE EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

A promising approach to improving Black students’ school experience involves training teachers to use restorative justice, focusing more on preventative strategies instead of punitive discipline.

In a notable example from Maryland, a set of “Positive Behavior Intervention Strategies” using restorative practices led to a 50% reduction in suspensions and a 95% reduction in referrals to the principal’s office. Most remarkably, when disciplinary action was required, these strategies resulted in an even distribution of discipline among students of different races.

IMPROVE EMPLOYMENT PROSPECTS AND CAREER DEVELOPMENT

One promising practice is to revisit job postings and look for hidden biases. For example, the Johnson & Johnson corporation saw a 9% increase in the number of women applying for roles after using software to adjust job postings and remove gender-coded language, business jargon, and laundry lists of skillsets not required. The same approach could be used for the Black community.

One Black rising leader gave us an example from her line of work: “Black women are pretty highly educated – but there’s a real barrier around language in postings that’s often used to exclude. Like when using the word ‘philanthropy’ instead of ‘fundraising’ - philanthropy is very White, but fundraising is broader and more Black people have that experience.”

In terms of career progression, developing formal sponsorship programs can be a big unlock for Black employees. According to our research, Black employees are five times more likely than White employees to describe a sponsorship program as “the most effective program for racial and ethnic diversity and inclusion” that their company could put in place. And yet, only 11% of Canadians in a 2019 survey report that their company has a formal sponsorship program.

The effects of these programs are material. Citibank developed a program to match high performing women with a senior advocate who served as their sponsor. 70% of women in the program advanced in their careers over the next 18 months. Accenture tied engagement in sponsorship to performance evaluations for its leaders – which led to a 20% increase in the number of minority employees up for promotion at the senior executive level.

SUPPORT A FOUNDATION FOR BETTER HEALTHCARE ACCESS

More Black representation in the medical community can help Black patients feel more comfortable – something recognized by the University of Toronto medical school. Its Black Student Application Program (BSAP) offers an optional application stream for students who identify as Black. Since the inception of its BSAP, the number of Black students admitted to U of T medical school grew from 1 in 2017 to 24 in 2020. The rest of the Canada’s medical schools could adopt a similar program.

Offering care more tailored to the Black population can further make a difference. For example, the introduction of a culturally adapted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy at the Women’s Health in Women’s Hands Community Health Centre in Toronto led to a 90% reduction in Black women visiting hospital ERs for mental health issues.

REDUCE POLICE BIAS AND VIOLENCE

Reforming police standard operating procedures is an effective tool against all police uses of force which disproportionately impact Black people. These include adopting policies such as a use of force continuum that sets out which weapons can be used in what circumstances and requiring by-stander officers to intervene if a fellow officer is using excessive force. Research has shown that more restrictive use of force policies can reduce killings by police by as much as 72%.

Changing police hiring practices to be more inclusive can also make a big difference. In one example from the U.K., new hiring directives increased the share of ethnic minorities in a local police service by 1.5% -- leading to a 39% reduction of minorities subject to stop and search, and 11% fewer complaints against officers.

Moving towards an inclusive future

Despite the challenges, there is a reason for optimism. Black communities in Canada are young and resilient. By acting now and removing systemic barriers, we can work with Black individuals to ensure they are on more equitable footing with other Canadians. We need leadership to drive a collective effort across Canadian society.

There are many actions we can and must take to start to eliminate anti-Black racism in Canada and drive lasting change. It starts on the individual level, where we encourage Canadians to speak up, identify inequities, commit to action, and become allies in the movement for change.

What can I do as a first step? Share this report with others in your network or organization and have a conversation about anti-Black racism in Canada and how it shows up in our society.

We encourage employers to commit to act by adopting inclusive practices to help ensure Black candidates and employees have a fair and equal path to jobs and career advancement.

What can employers do as a first step? Create an open dialogue with your leadership teams and workforce to understand how anti-Black racism shows up in your organization.

CivicAction is committed to facilitating these actions by bringing leaders together, supporting the development of new relationships and accelerating Black representation at the leadership level.

Moving forward, we encourage all Canadians to hold our leaders accountable so that they sustain their commitments to support Black communities.

Subscribe to read our latest insights on Inclusive Advantage

About Our Research

This report is a summary of the research completed by BCG in partnership with CivicAction during the summer of 2020. The work was initiated through a mutual goal to shed a light on the pervasive and systemic biases that are experienced by Black communities in Canada, with the collective goal to drive to meaningful action.

Areas investigated were identified in the framework developed by the Toronto Action Plan to Confront Anti-Black Racism, then further prioritized to focus on specific topics within those issue areas. We chose topics where an active body of research already exists, and actions can be taken at the local level. It is important to note that this summary is not exhaustive, and other important topics were not investigated, such as the justice system within the broader “Policing and the Justice System” issue area, as well as the “Community Engagement and Black Leadership” issue area. These are rich areas for further factbase development.

We acknowledge and appreciate the contributions and insights of numerous rising and risen leaders, academics, activists, doctors, and policy experts in Canada’s Black communities. This includes the executive director and committee chairs of the BlackNorth Initiative, along with its founder, Wes Hall. We incorporated their perspectives together with data from multiple sources including: Statistics Canada, BCG Centre for Canada’s Future Diversity and Inclusion Survey, the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, the Black Health Alliance, the Black Experiences in Health Care Symposium, and reports by the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Toronto District School Board, and Women’s Health In Women’s Hands CHC. Data and studies were also collected from literature and press searches from Canada and abroad, and were the best known sources at the time of the research. Finally, we want to extend our thanks to the BCG team members who were dedicated to creating the factbase and this report: Puneet Gupta, Gillian Cook, Kasey Boyle, Kate Banting and Prerna Sharma.

About CivicAction

A leading not-for-profit in Canada, CivicAction has nearly two decades of experience working to boost civic engagement and build better cities by creating and implementing effective solutions to the most pressing challenges in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area and beyond. To find out more, visit

https://www.civicaction.ca

or follow @CivicActionGTHA.