Imagine that you are a Chief Information Officer or an IT functional leader in a major enterprise. The COVID-19 global shutdown has given you a choice. You can cut costs across the board as best you can, or you can seize the day, and take the opportunity to make a step-change advance in the way you organize your IT workforce. This can help you reduce costs while strengthening your company’s digital prowess—bolstered by trends in technology and management, along with some of the behavioral changes prompted by the shutdowns. The measures you can take include reorganizing your staffing priorities, reconsidering your sourcing options and moving some capabilities in-house, consolidating your service provider footprint, and optimizing your delivery center network.

Waiting for recovery is not an option. The uncertainties of the current moment make cost optimization an urgent priority for nearly every company, and G&A expenses are no exception. Until a permanent medical solution is available, the crisis will continue to place a great deal of stress on most companies. Still, it is prudent to look ahead at the advantages that will be needed in the future , and to design today’s cost-cutting measures accordingly.

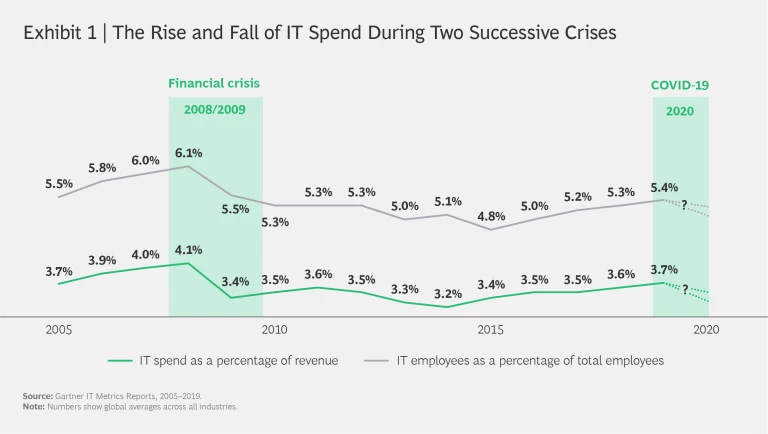

When it comes to IT costs, the talent mix is crucial, since roughly 30% to 40% of a company’s IT spend is directly related to internal staffing costs and another 20% is related to external contractors. Following the 2008 financial crisis, IT spending in companies dropped abruptly from 6.1% of revenue to 5.5%, and the percentage of employees working in the IT function dropped from 4.1% to 3.4%. (See Exhibit 1.) That crisis also led to a significant shift in the IT footprint from locations with higher-cost talent to lower-cost locations, using either in-house global capability centers (GCCs) or external third-party providers (TPPs). Companies will feel a similar pressure to outsource this year.

At the same time, the demand for sophisticated digital services, and thus for high-quality IT talent, will continue to rise. The current crisis will accelerate this. There is likely to be rapid growth in the digitization of customer journeys, now that more consumers are familiar with online purchasing. The crisis also represents a likely inflection point for increased adoption of cloud-based services, telecommuting, and agile ways of working—especially given many employees’ sudden, direct experience with social distancing, working from home, and virtual organizations.

Even before the pandemic, there were already reasons to reconsider your outsourcing, co-location, and security practices , and now there are other questions to consider. If working from home becomes commonplace in many companies, will this foster greater decentralization generally? If teams can work easily by remote connection in the same metropolitan area, will business leaders want them to also work remotely from different locations around the world, including places with greater talent availability and lower costs of living?

Other macro variables are also in play. Cyber and information security will be more of a need than in the past, and artificial intelligence will be further embedded in business capabilities. The shift from globalization to nationalism may continue, making it harder to attract staff from other geographies and to enhance investment in R&D and manufacturing near company headquarters.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for IT talent was far greater than the supply. According to the Wall Street Journal, there were more than one million open IT positions in the US alone in late 2019, and many Western European countries faced similar talent shortfalls. The pandemic has led to widespread hiring freezes, but the need for tech talent is still strong, and companies are expected to begin competing for it again relatively soon. In the face of all these trends, as a CIO, you will need to think more strategically than ever about the way you organize, support , and deploy your IT talent. Reducing staff across the board today could hurt your ability to deliver services tomorrow.

You will need to think more strategically than ever about the way you organize, support, and deploy your IT talent.

Analyzing Your Staffing Archetypes

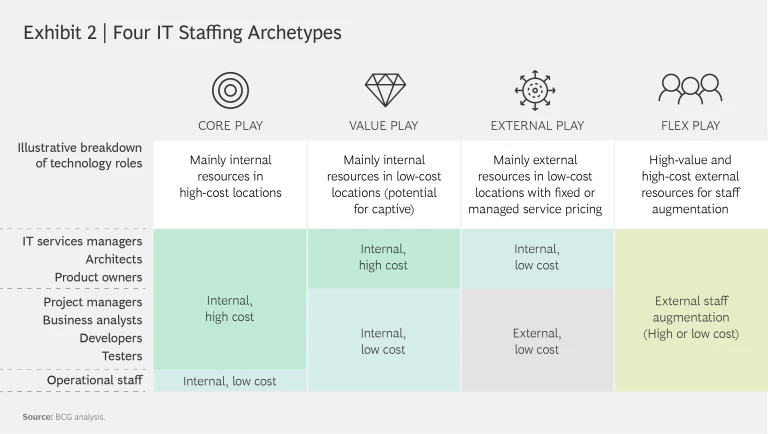

Your technology talent typically falls into one of four basic archetypes arranged by value proposition, as shown in Exhibit 2. When you analyze your IT function, you’ll see that among the activities you assign to each archetype, some fit perfectly, while others do not. Your first challenge is to dispassionately discern which groups are ill-matched, and adjust accordingly.

The Core Play. These are teams whose work is identified as critically important to the company’s primary, differentiating businesses. A core play endeavor should either make a direct contribution to the company’s overall strategy, or ensure alignment of IT services to business needs in other distinctive ways. A company’s primary digital presence is designed and developed in the core play domain.

Core play teams should be heavily insourced to retain knowledge and help build enterprise capabilities, as well as to work closely with their counterparts in the rest of the business. Only a small fraction of core play talent should be external: these are often high-priced consulting firms highly specialized in fields like machine learning or management consulting. As companies embrace remote collaboration, some core play activity may migrate to remote areas, but always with a high level of interaction with critical functions or senior management.

The Value Play. The second group provides elements of the company’s critical operations, but at a lower cost, generally because they can be moved further from the center to lower-cost geographies. Value play teams are often organized in so-called “captive subsidiaries.” These wholly owned talent suppliers help attract talent and build capabilities, but may require scale for efficient operation. Value play teams have often worked in GCCs on back-office systems, where the data may be too sensitive to trust to an outside firm.

In recent years, companies are shifting application development and maintenance activities from core play to value play. As general business activities, like some finance and marketing endeavors, move to lower-cost locations, IT teams may also shift to ensure co-location with those businesses.

The External Play. This archetype typically involves external contracting firms with a small “retained organization” of internal staff to oversee them. External play teams manage IT for operations, such as payroll, benefits management, or for foundational infrastructure services like a help desk, end-user support, and server or storage management.

These “keep-the-lights-on” functions are often critical to the business, but not strategically important or specific to an industry. TPPs are well-suited for them because outside contractors have built up specialized expertise that most other companies can’t equal. Great value can be captured from contracting out this full scope of work through managed service agreements that also provide resources to staff value play projects at an attractive rate.

The Flex Play. These teams include staff assigned in an ad hoc fashion, or external consultants who provide specialized expertise or who can substitute for staff at moments of crunch or crisis. Staff augmentation of this sort tends to be comparatively expensive and thus should be used only in moderation for limited periods.

Over-reliance on this archetype is dangerous because it can become habitual in the long run, inflating staffing costs and drawing resources away from the development of internal capabilities. In system terms, this creates a negative feedback loop that undermines your company’s digital growth. To avoid this pitfall, set a goal of replacing dependence on this archetype and moving activity to the other three strategic plays.

Opportunities for Action

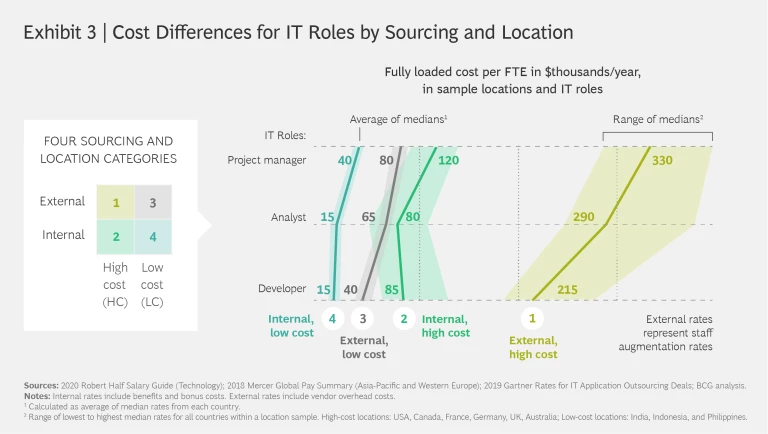

Exhibit 3 shows the four most prevalent categories of IT staff members, based on sourcing, location, and whether the talent is internal or external. Each category is represented by a vertical line surrounded by a wider band, representing the range of salaries for each category in three particular job groups: project managers, analysts, and software developers.

The cost of employment is highly dependent on geography. High-cost talent—often associated with core play activities—tend to live in cosmopolitan areas, often located near the company’s headquarters or in core city centers in countries like the United States, Canada, France, Germany, the UK, or Australia. Low-cost talent—often associated with value play—tend to be located in places with comparatively lower salaries, such as Southeast Asia, most parts of India, and some locations in Eastern Europe.

The cost variance between the extremes of high-cost external workers and low-cost internal ones can be jaw-dropping. For example, suppose that a technology firm located in Germany or Canada hires a full-time, internal project manager. An individual working in India or the Phillippines would require one-third of the expense of comparable internal talent working at headquarters.

The comparative savings can be even greater for external resources. On average, according to salary data gathered from around the world, a year’s full-time equivalent (FTE) for contracted project management might cost $80 thousand when based in India or the Phillippines. Similar talent, working at typical staff augmentation rates in a European or North American city might cost $330 thousand for a year’s FTE (and even when better contracting rates are negotiated, the costs are still relatively high.) There are similarly wide rate-card differentials between analysts and developers in low-cost and high-cost locations, for both internal employment and external sourcing.

Of course, there are reasons you might prefer a higher-cost alternative, if you need someone closer to headquarters, or with particular skills not available in other geographies. But all too often, the sourcing and location of IT staff has evolved in ad hoc pockets of activity, without any deliberate comprehensive decision about overall staffing patterns. The result is overspending for less value.

Now consider each domain of activity within the IT function. These would typically include governance, security, business relationship management (BRM), application development and maintenance (ADM), infrastructure, and operations. Think about the choices that you could make deliberately in each domain. When should you staff internally versus externally? When do teams need to work in high-cost locations? Which vendors provide the most value, and when should you use them for what tasks? Changing your approach to these questions enables you to rationalize your choices more comprehensively.

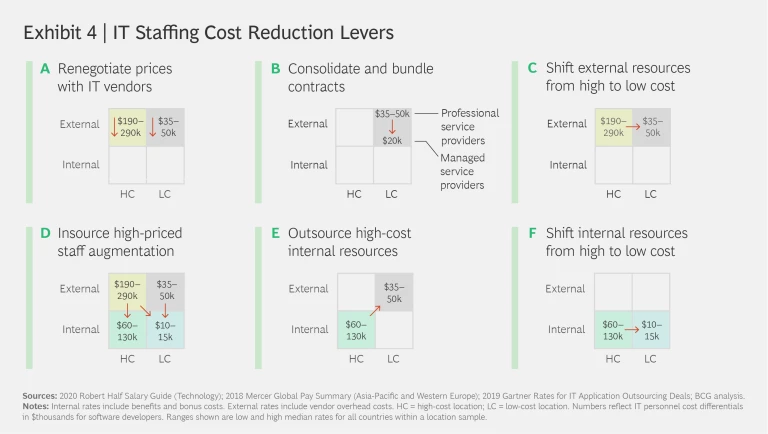

Exhibit 4 provides a starting point, with six possible levers you can apply to change the cost dynamics. The following actions provide a different way to reduce expenses without losing digital capability and are relevant to some of the activities in each domain:

- Rework deals with external vendors. Our work with clients suggests that many companies ask their IT vendors for a price discount of 10% to 15% during times of disruption. Additionally, you may rethink the length and scope of your outsourcing contracts to meet a lower overall target and cut back nonproductive services.

- Consolidate activity across a smaller group of external vendors. This will afford you greater leverage and the ability to devote less staff attention to managing the relationships. Some companies have hundreds of small-staffing vendors, and would be better served with a carefully handpicked group. Consider one of the giant managed service providers that have thousands of staff members with IT specializations your company couldn’t match.

- Shift your external staff to equivalents that are less expensive. These will typically be located in lower-cost geographies, with capabilities equal to or greater than those of your current external providers. This shift can also be accomplished with your existing providers by asking them to provide a lower-cost delivery model with their own shift in locations.

- Insource your outsourced external activity to lower-cost categories. Bring work done by high-priced external consultants in-house—either by moving the work to new people, or by making the right full-time hires.

- Manage your high-cost internal resource footprint more effectively. This typically means relocating work done by staff professionals to lower-cost external providers (lever E) or lower-cost geographies (lever F), as many have done with call centers, for example. As functions like finance and HR move to these locations, the IT activities related to those functions may move with them, although typically IT has led the charge with business operations following.

Some companies may have other means of reducing staff costs, such as temporary leave or sharing staff with other companies. But the six levers are universally applicable and relatively scalable; you can apply them to parts of the IT function, or to the whole.

For short-term actions to help you weather the downturn, focus on lever D to reduce your dependency on highly expensive staff augmentation. Even in a sharp downturn, look to insource talent instead of extending contracts with high-priced vendors. Challenge your IT vendor management team to better forecast future demand in an effort to avoid situations when your only option is to go for last-minute, ad hoc external staffing. Finally, ask your managed service provider if they can offer flex play capacity at a reasonable rate.

Even in a sharp downturn, look to insource talent instead of extending contracts with high-priced vendors.

Rethinking Your IT Function Teams

Each of your existing IT functions has probably gravitated to one predominant sourcing and location archetype. Assemble a team of IT leaders to look closely at your activities and see how they are currently handled, and how they might be reframed.

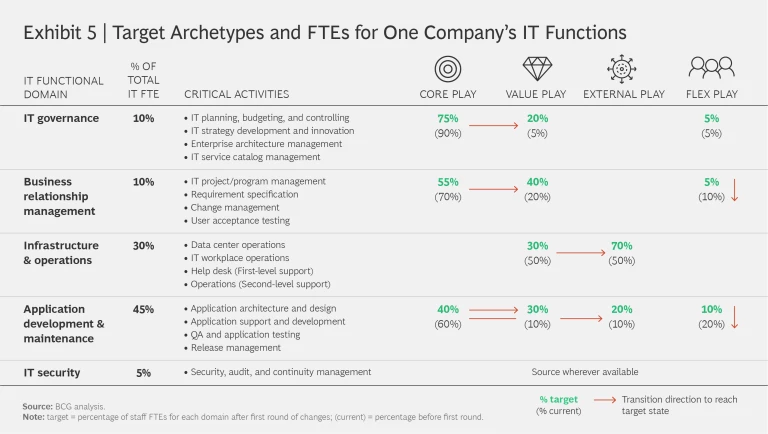

Exhibit 5 shows one such analysis for a global professional services provider, leading to a better approach for cost savings and strategic alignment to be implemented in the near future. A few high-level takeaways:

- For this enterprise, IT governance is currently a core play function, closely aligned with business leadership and essential to differentiating the company. Nevertheless, appoximately 20% of the function will be moved to a value play arrangement, using primarily staff in lower-cost areas. In addition, flex play activity will be brought inside.

- When it comes to BRM—also a core play function, which governs connections with customers, vendors, platforms and IT-related aspects of the supply chain—the firm will move much of its activity to the value play. This move fits with a more general IT trend, as other companies in this sector are also moving business operations to lower-cost locations. Some external play activity could be moved to value play or even core play as well, if it is strategically relevant.

- Infrastructure and operations is currently divided between value play and external play activity. Analysis suggests that external vendors can handle more of this activity, largely because of their specialized expertise in data center operations. With contracts oriented toward guaranteeing data privacy and reliability, and a high level of trust and collaboration on both sides, 70% of this activity will move to external play.

- A more elaborate decision process is needed for application development and maintenance, the largest group of activities. Currently, most activity is located near headquarters, in a US metropolitan area. If it is related to industry-agnostic, back-office activities such as tax and payroll, it will move to external play. If it is oriented to maintaining critical operations, but with very little new R&D involved, it will move to value play. The remaining work will stay in core play, but much of it will shift to a more agile way of working, bringing IT and business leaders together in cross-functional teams.

- The IT security category, unlike the others, does not have a definitive target play because of this fast-moving field’s talent shortage. The company will recruit from any available source, including high-priced external vendors. This is the one group which, if no other resources are available, will accept the flex play archetype.

Taking the First Step

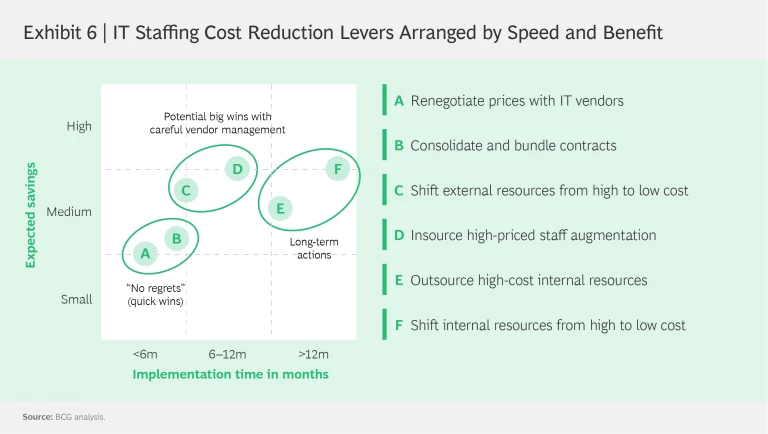

During the next few weeks, you will need to demonstrate your ability to manage expenses for the short term. Therefore, start with the most immediately productive exercises—identifying “no-regret” approaches that offer quick wins. (See Exhibit 6.) These typically involve IT staffing cost-reduction levers A and B: moving internal resources that were in the core play domain to the external play and value play, respectively. In global companies, 40% to 50% of IT teams are typically organized as core play teams and thus have a higher price point than may be needed.

Lever A enables you not just to cut costs, but also to find untapped opportunities for capability improvement. Many companies have struggled for years with a fragmented IT vendor landscape. Here is an opportunity to consolidate. Some IT leaders have been reluctant to use external vendors, including some of the largest vendors based in India, because they think the quality is poor. But many vendors have an excellent track record, and managed service contracts can lay out the parameters clearly enough to avoid much risk. Additional savings can be achieved by negotiating lower rates, or by consolidating to a handful of vendors who will offer discounts in exchange for a larger scope of work.

Meanwhile, start now to work on levers C and D: shifting activity from high- to low-cost external vendors and bringing high-priced staff augmentation in-house, respectively. These are potential big wins, although they may involve careful vendor relationship management and could take a longer time to implement. For many reasons, getting contracts renegotiated and signed may take as long as two years. Europe’s generally worker-oriented legal frameworks may make it difficult to move people, while some external contractors may prefer to remain external and will take convincing to join your organization. A hiring freeze may prevent you from making an offer, even if it would save money after a month or two.

If you persevere, however, the savings with levers C and D can be enormous. Our previous analysis of staffing costs suggests that the average cost of one year’s FTE could drop significantly. For software developers, for example, the price goes from $215 thousand (external high-cost staff augmentation) to around $85 thousand in internal high-cost locations, or to just $15 thousand in internal low-cost locations. Quality considerations would need to be made on a case-by-case basis, of course.

As for the last two levers—which essentially entail shifting resources from the flex play to the core and value plays (E) and the external play (F)—they, too, are sources of great savings over the long term. To execute, reassess which flex play activities might be less critical and can therefore be transitioned to the less expensive value or external play functions, with similar quality of service. You’ll find that there is a great deal of untapped talent in remote geographies. Use the downtime brought by the pandemic to build up the requisite management capabilities that ensure high-quality GCCs and IT services in low-cost locations.

In general, external consultants can bring much-needed insight and perspective, but if they have been running significant parts of your IT function, then it may not be as differentiated as you need it to be. As you bring that expertise in-house, your own distinctive form of digital proficiency could become a way of life.

Each company is different, so no “one-size-fits-all” approach exists, and your combination of role changes, levers, and archetypes may include some elements that are not highlighted here. Nevertheless, these universal principles represent a good starting point for any company’s analysis—and they can help you save immediately and in the future.

This IT staffing strategy will also help you pursue other IT staffing goals and prepare for the recovery that will follow the crisis. With it, you can evaluate your own staff’s current capabilities, as well as the capabilities needed to become a digitally enabled enterprise. You can consolidate and strengthen your provider portfolio while attracting, building, and equipping a skilled tech-savvy team of innovators and experts with the tools they need to work together in a more agile way. You will be able to increase your company’s productivity and efficiency, and if you are skillful in the way you organize talent and learn on the journey, then you will also augment your IT executives’ skills as leaders: as the people who will continually enable your company to be successful in the digital age.