Five years after the Paris Agreement, the state of global climate action is still dramatically insufficient.

While emissions have dropped during the economic shutdown caused by the pandemic—early estimates show a decline of 5% to 10% in 2020 from 2019—the structural challenge of a carbon-driven economy remains the same. The slow progress in collective action from international climate negotiations turns the spotlight on what individual corporations, investors, governments, and ultimately, citizens can do to prevent an irreversible global crisis.

Conventional wisdom holds that taking individual action against climate change is a classic example of the “prisoner’s dilemma,” in which rational parties prioritizing their personal interests can create a worse situation for everyone. The assumption is that it is costly for any one business or institution to reduce emissions unilaterally because they risk disadvantage if others do not move at a similar speed.

This narrative is flawed.

Companies from every sector can do much more to reduce emissions intensity throughout their businesses and supply chains with measures that cost them little or nothing.

Companies from every sector can do much more to reduce emissions intensity throughout their businesses and supply chains with measures that cost them little or nothing—all while seizing significant growth opportunities in low-carbon business models along the way. Where costs and technology risks are high, companies can overcome barriers through ecosystem action, collaborating throughout their value chains, or by agreements with industry peers. Investors, too, have an incentive to scrutinize their portfolios for long-term carbon-related risks that would erode value, and to push companies to lower emissions and build resilience. Finally, many governments can realize economic benefits from investing in emissions reductions, even in the absence of collective action. They should reduce emissions much more rigorously without fearing a decline in economic competitiveness.

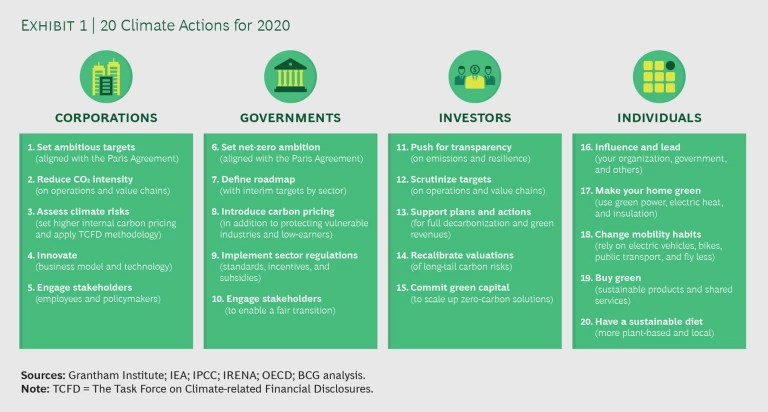

The short-term solution to the climate challenge lies in individual action. While no single entity can halt global warming alone, those that take the lead in implementing key climate actions can have a positive multiplier effect. (See Exhibit 1.)

Our joint report with the World Economic Forum, The Net-Zero Challenge: Fast-Forward to Decisive Climate Action , assesses the current state of climate action and outlines what all players can do to mitigate climate change—and finds that taking action can be a source of significant competitive advantage. (See the sidebar.)

Report Highlights

Report Highlights

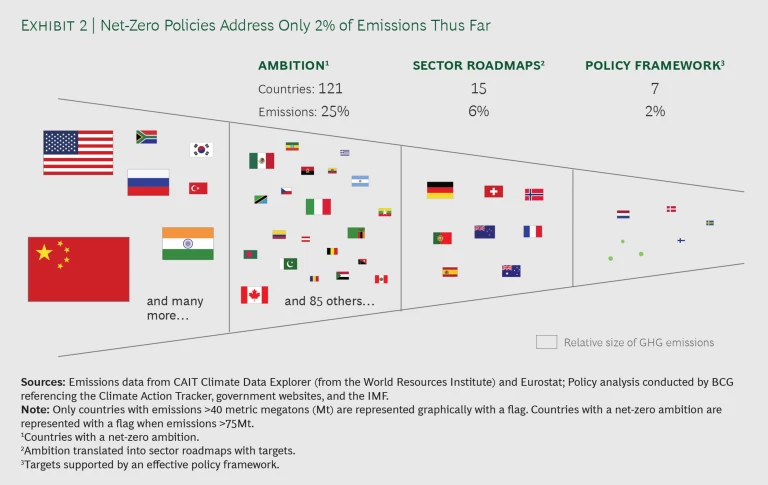

Progress on climate action is still dramatically insufficient. As of January 2020, 121 countries have committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2050. However, these countries account for less than 25% of emissions and very few have enacted policies that are robust enough to produce the desired effects. To deliver on the Paris Agreement, a structural turnaround in net greenhouse gas emissions is still needed.

There is no “prisoner’s dilemma.” All players—businesses, investors, and governments—can benefit from moving ahead unilaterally.

Businesses can turn climate action into a source of competitive advantage. Climate action can be a driver of cost reduction, innovation, and differentiation in a competitive environment, according to more than 40 business leaders who were interviewed for the report.

Ecosystem initiatives can overcome barriers to individual action. Where barriers to transformation exist, such as in sectors where decarbonization costs are too high for individual companies to bear alone, collaboration with industry peers and along value chains can provide a solution.

To manage risk, investors should push for net zero. Investors will be the first to feel the impact of carbon risks materializing. It is in their self-interest to promote disclosure and push companies to bring down emissions or adopt resilient business models aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Governments need to regulate emissions. Solving the climate crisis ultimately requires more regulation. Even though progress in international negotiations remains slow, more governments can accelerate national action while remaining economically competitive. In most countries, even unilateral climate action can spur growth.

The world is at a crossroads: we must fast-forward to decisive and cohesive action. The technologies for a low-carbon transformation are largely available, the paths to decarbonization are understood, the barriers to action are vastly overstated, and the consequences of inaction are well known. Climate action should be viewed as an opportunity to create an advantage in building a better, more sustainable world.

The State of Climate Action Is Dramatically Insufficient

Despite recent commitments from governments and companies, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise by 1.5% per year over the past decade. Should this pattern continue, the world is projected to warm by 3°C to 5°C by 2100, with catastrophic effects on human civilization. We need to reduce global emissions between 3% to 6% annually by 2030 in order to limit warming to a safe range of 1.5°C to 2°C, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). We must reach net-zero emissions by 2050 for the best chance of avoiding irreversible damage to the planet.

More than 120 countries have made their net-zero ambition clear. Still, these countries account for less than a quarter of all global emissions, and many of the world’s largest emitters are not doing enough to address the problem. China has reportedly resumed construction on the world’s largest pipeline of new coal power plants. In the US, senior government officials have openly denied climate science, backtracking on previous regulations and international commitments, including the Paris Agreement. Even the front-runners are off track. Only seven of the countries committed to net zero have broken down their goals into intermediate sector-level roadmaps backed by policies that could realistically trigger the reductions. Their combined GHG emissions account for less than 2% of the world’s total. (See Exhibit 2.)

The apparent failure of governments to act increases the responsibility of corporations to fill the void. However, of the millions of corporations worldwide, only 7,000 provide climate-related data to the UK-based organization CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project), which aims to make environmental reporting a business norm. Even among those that do report targets, most fall below the requirements set by the Paris Agreement.

Investors, acting both alone and through activist groups, have started to put pressure on companies to better understand and disclose their carbon-related risks and develop resilience strategies. At the same time, increasing public awareness has helped citizen groups gain momentum. Nevertheless, pressure is still not building fast enough on a global scale. Without a significantly accelerated structural shift, the world will simply resume emissions growth after the COVID-induced slump. The good news is that for most parties, climate action will work to their benefit.

Companies Can Build a Competitive Advantage on Climate

Companies can benefit from moving on climate.

For one thing, most can still realize energy- and process-efficiency gains in the range of 20% to 40%, with positive standalone business cases and comparatively short payback periods.

In addition, it is in their interest to de-risk their portfolios for the low-carbon transition. Nearly all current investments in coal, and an increasing share of investments in oil, gas, and related infrastructure would not be compatible with the IPCC’s abatement scenarios. As a result, there is a risk that such investments will become stranded, no longer able to produce returns if the regulatory environment changes. Even industrial companies should therefore make their investments in new assets, long-life asset upgrades, or new product development with a carbon-neutrality target in mind, so that they can avoid potential future write-offs. Finally, new markets for lower-carbon products are taking shape and many companies are generating significant value from credibly serving them—by decarbonizing rapidly, by offering consumers a “green choice,” or by innovating to help customers reduce their own emissions.

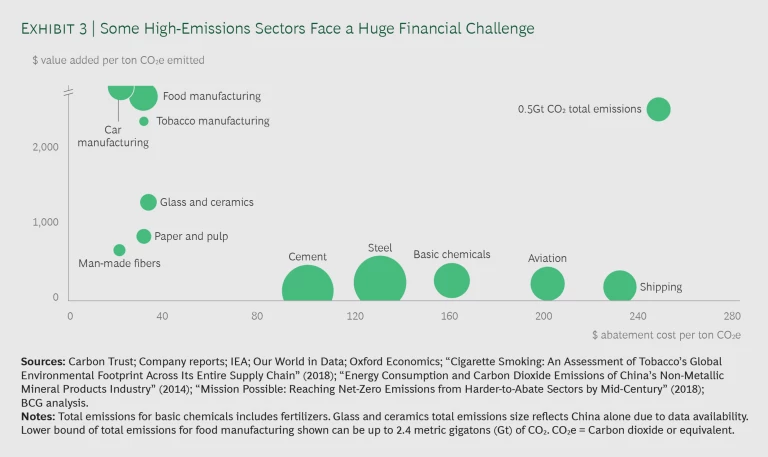

Nevertheless, challenges do exist. For many companies in high-emissions sectors such as steel, cement, chemicals, aviation, and shipping, investments in ambitious emissions reduction pose an enormous financial challenge and an existential risk. (See Exhibit 3.) Accordingly, in those industries where low-carbon solutions are still in pilot stages or do not have a viable business case to back their use, business leaders can enable bolder climate action by working in ecosystems with peers, suppliers, customers, and governments. In the face of technological uncertainty and expensive scaling, ecosystem collaborations can allow players within a sector or across a value chain to share costs and risks.

In sectors where the market for low-carbon products is uncertain, collaborative efforts can create a critical-demand signal to kick off a market. Where a lack of climate policies has left businesses with no incentive to act, industry coalitions can overcome this paralyzing dynamic through joint commitments or standards, and through self-regulating bodies in areas where government policies fall short. Examples of such organizations include RE100, which pushes corporations to commit to 100% renewable energy, and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which is developing a voluntary climate-related financial risk disclosure standard for companies.

Finally, ecosystem action can help leverage the power of public scrutiny when it comes to building momentum for emissions reductions and can signal commitments to action among large firms. Many corporations now set emissions goals through alliances such as the Science Based Targets initiative, CDP, and the Step Up Coalition.

Investors Should Manage Their Carbon Risks

Investors have a pivotal role to play in motivating companies, given their inherent interest in de-risking the terminal value of their investments. They should issue a much stronger call for transparency and disclosure, thereby forcing companies to increase their own awareness of climate-related risks and the potential for greater economic efficiency through climate action. Disclosure requirements would also make assessing these risks more straightforward for investors and create better comparability among industry peers, hence increasing the efficiency of capital markets.

Investors have a pivotal role to play in motivating companies.

Moreover, investors should recalibrate their own risk assessments to better understand the impact of various warming scenarios on their assets—including operational disruption, health and safety, and site-closure risks. The long-tail risks of both climate change and climate action should be reflected fairly in the valuations that investors assign to companies. Finally, investors can direct their capital into zero- and low-carbon technologies and offerings. A growing appetite for green bonds and other sustainable finance products sends a powerful signal that support exists for decarbonization initiatives.

Governments Can Boost Growth by Addressing Emissions

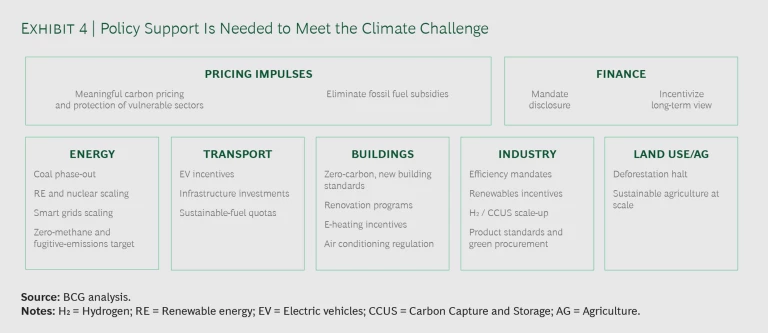

Individual and corporate action can accomplish a great deal, but ultimately, they cannot win the fight against climate change without the support of government regulation. To lower emissions, governments should eliminate fossil fuel subsidies and introduce meaningful prices on carbon emissions, while at the same time introducing ambitious sector-level policies. (See Exhibit 4.)

Contrary to common belief, many countries stand to benefit economically from regulating carbon emissions. The Economic Case for Combating Climate Change if countries prioritize the most efficient emissions reduction measures. Even unilateral mitigation can have a positive economic impact because the required investments create significant stimulus. And while governments now face the immediate need to intervene with economic recovery packages in response to COVID-19, the best stimulus programs will also address ways to rebuild the economy for long-term climate resilience .

While first movers may need to find ways to safeguard heavy industry, the broader economic threat posed by climate policies is often overstated.

While first movers may need to find ways to safeguard heavy industry, the broader economic threat posed by climate policies is often overstated. An initial consideration is that a significant share of emissions is generated in sectors that are largely local, such as transportation, building, and power generation. Furthermore, in sectors that are not local, the threat of “carbon leakage,” which entails high-emissions-industry players moving abroad to stay competitive, thereby shifting but not reducing global emissions, is less of a problem than people realize. Truly “leakable” industry sectors with high-emissions intensities and high costs of abatement—steel, primary metals, base chemicals, and cement—make up less than 4% of the world’s GDP. A 2019 report by the World Bank’s High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing and Competitiveness finds, consequently, that setting appropriate sector-specific carbon taxes has only a negligible impact on competition.

This is not to say, however, that countries can afford to ignore leakage risk. In the absence of a level playing field worldwide, progressive countries will need to safeguard affected industries by imposing protective measures against high-carbon competition or supporting their emissions reduction journeys. But most of these countries are economically strong enough to support the decarbonization of the industries at risk, which are few enough that tailored solutions can be implemented as needed.

From Prisoner’s Dilemma to Shared Action

Ours is the last generation that can prevent a global disaster. If unchecked warming continues, the consequences for human civilization will be severe. Rising sea levels, extended heat waves, longer droughts, and extreme weather events will threaten food and water supplies and could disrupt development and economic growth. According to the IPCC, “no action” on climate change would trigger a decline of at least 30% in the global GDP by 2100—dwarfing the costs of climate action borne by any country. For many, investing in reducing emissions would even be a positive standalone business case.

We need a fundamental transformation of the world economy—but the effort can start with individual actions of key players. The “prisoner’s dilemma” narrative that discourages these individual actions is fatally flawed. Instead of perceiving climate action as a cost, risk, or trade-off, businesses, investors, and governments should see it as an opportunity for growth and competitive advantage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Miranda Hadfield for her contributions to this article.

BCG’s Center for Climate & Sustainability

We partner with clients across the public, private, and social sectors to align their strategy, operations, and stakeholder engagement with a low-carbon world. Our work is supported by BCG’s range of consulting experience across all industries and capabilities, as well as by our expanding reach of brands.