On the face of it, the recent OPEC+ deal to cut production looks like an abject failure. Far from recovering, oil prices took a historic nosedive in the aftermath of its signing and remain very low. Still, given that reductions are not scheduled until May, it is too early to write off the group’s efforts. If the OPEC+ members meet their commitments, the agreement may yet provide a boost to prices in the medium term and help manage the supply glut wracking the industry.

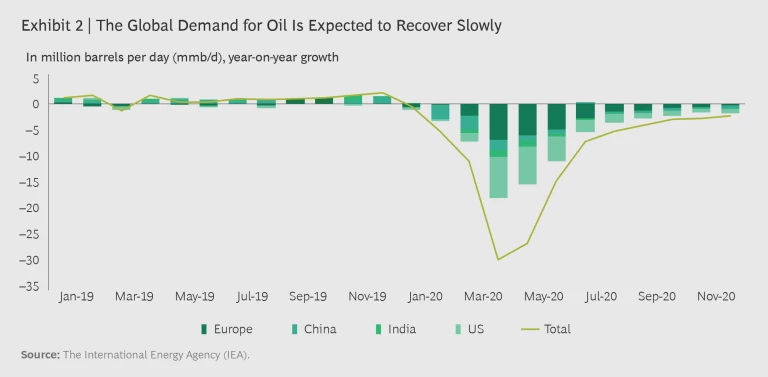

In the wake of an unprecedented demand shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was unreasonable to expect the accord to balance the global supply and demand for oil overnight. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts a demand decline of just under 30 million barrels per day (mmb/d) for April, and an average of 18 mmb/d in the second quarter. A cut of this magnitude would have left OPEC+ states with almost no short-term revenue and jeopardized their long-term production capability.

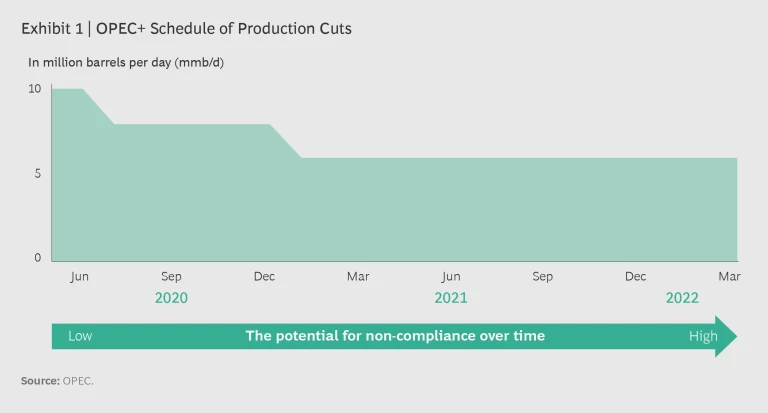

The group’s decision to reduce production in both May and June by 9.7 mmb/d, and to lower future cuts gradually over the subsequent 15 months, is still a major, welcome commitment after a previous agreement fell through in early March. The decision suggests that OPEC+ members are aiming to restore market balance over the next 18 to 24 months, while gradually strengthening oil prices in the process. If fully implemented, the deal would reduce supply by an average of more than 8 mmb/d this year (much closer to the IEA’s current 9.3 mmb/d estimates for average demand decline in 2020), and by 5.8 mmb/d in 2021, when some demand growth is expected.

The efficacy of the deal will depend on the eventual size and duration of the global demand loss, the pace of demand recovery, and OPEC+ compliance. (See Exhibit 1.) Of course, only the last of these factors can be controlled by OPEC+ members. Past compliance with agreed production cuts has been relatively high during periods of acute crisis, with over 80% of OPEC members complying, on average. But as prices picked up, some members lessened their commitments to take advantage of the recovery.

However, except for Iraq during the United Nations sanctions in the 1990s, no OPEC+ member has faced a fall in demand of this scale before, so the incentive to maintain cooperation is high. (See Exhibit 2.) Moreover, in a world of weakened demand, the risk of overproduction will be curtailed by increasingly limited global storage and the absence of markets for additional barrels. As weak demand persists, many OPEC+ states may be forced to cut production in the short term even more sharply than they’ve agreed to in the deal.

The deal will inevitably be adjusted before it runs its full course, once a clearer picture emerges of the full extent of the recession and the true pace of demand recovery. But because the OPEC+ members have a fiscal incentive to address the supply overhang as quickly as possible, they are likely to stick with it until balance is restored. As a result, the deal may well help oil markets and prices to recover in the medium term and go some way to restoring the industry’s fortunes.

Nevertheless, with any recovery in prices set to be a gradual one, the financial pressures on producers and oil and gas companies will continue for some time. Companies and governments that rely on higher-cost production are especially vulnerable to project delays or cancellations, though these are likely to occur across the industry. For oil-producing countries, painful budget cuts are inevitable, as prices will not recover sufficiently to meet their fiscal revenue needs until 2021, at the earliest.

While there is no panacea, the producers and companies most likely to emerge from the crisis in reasonable shape are the ones that will be able to reduce operating expenses and introduce new technology to take out costs, prioritize capital discipline and free cash flow generation, and shrewdly manage their portfolio to minimize exposure to high-cost production.

About the Center for Energy Impact

The Center for Energy Impact (CEI) aims to engage a changing industry in new and different ways by providing challenging ideas to drive performance. We shape thinking about the future availability, economics, and sustainability of the world’s energy sources—and the implications for energy companies and their portfolios.