Around 2015, people in the media industry started using the term “peak TV” to describe the point at which no more TV shows could possibly be created. Five years later, this hasn’t happened.

Instead, those five years have been a very good time for most of the participants in the video content ecosystem, starting with consumers, who have had more high-quality content to choose from than ever before. Content creators and producers have ridden strong demand to new heights. Broadcasters and streaming players have had to manage the fast-rising costs of developing and acquiring new content to stay ahead of the curve and the competition, but they have also enjoyed strong demand from viewers. The pandemic has provided an extra boost as consumers look for new sources of entertainment and diversion.

That said, as content producers deal with the production constraints that COVID-19 has imposed, and as content buyers assess the shape of a post-pandemic video marketplace , the question of peak TV has reemerged. Is the bubble finally set to burst—or at least deflate? What will be the impact on various market participants if it does?

The Bubble Is Still Expanding

In the last 15 years, several waves of new players entering the space have inflated the video content bubble. The first was the rise of digital platforms built around user-generated content, such as YouTube, Dailymotion, and Youku in China. The next wave saw the surge in over-the-top (OTT) video providers such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, iQIYI, and Viaplay. The most recent wave saw the expansion of the OTT universe as both tech companies and traditional media companies have gone direct to the consumer with their own OTT launches (Apple TV, Disney+, and HBO Max). They have been joined by short-format specialists such as TikTok and Quibi, and networks such as WWE, ESPN+, and Shudder.

Streaming content has become a major market force. Social media and livestreaming platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, Twitch, and Cheddar, have attracted millions (in some cases, billions) of viewers. As of February 2020, the top 20 global commissioners of scripted content included nine OTT companies. And the lines have blurred, with OTT platforms such as Tencent and iQYI also becoming big buyers of scripted TV shows. Netflix set a record for Emmy nominations in 2020 with 160.

The numbers are enormous. Netflix’s 2020 estimated content budget of $17.5 billion is bigger than the GDP of 75 countries. New launches are adding to the deluge: three new US OTT services (Peacock, HBO Max, and the forthcoming Paramount+) are expected to add 44,000 hours of film and TV programming to the 53,000 hours available from Hulu and the 44,000 available from Netflix, along with those available from other providers.

At an estimated $17.5 billon, Netflix’s 2020 content budget exceeds the GDP of 75 countries.

Content production has become an increasingly global business. Turkey is now the second largest exporter of TV content after the US. Turkish TV shows are currently being broadcast in some 150 countries. Korean-made content has developed substantial diversity and depth and has been reaching audiences across Asia and beyond. The Korean movie, Parasite, is the first non-English language film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards. In 2019, Netflix signed long-term contracts with two Korean production companies.

Spain is another fast-rising production center for multiple reasons, including relatively low costs, tax incentives, a wide variety of geographic locations, good infrastructure, and a deep talent pool. Netflix chose Spain as its first international production hub and increased its Spanish-language content by nearly 30,000 hours from 2018 to 2019.

The Rising Costs of Too Much Choice

Global spending for content has skyrocketed, almost doubling from $87 billion in 2010 to $160 billion in 2020, with $39 billion paid for sports rights, $52 billion for film and TV rights, and $69 billion for original content (up from $47 billion 10 years earlier). Broadcasters’ (including public broadcasters) share of spending has shrunk from 90% to 65%. OTT services now represent 17% of all content spending.

Two factors point to the possibility of trouble in this high-priced paradise. One is consumer exhaustion. The other is that content buyers have a tough time making money as costs continue to rise.

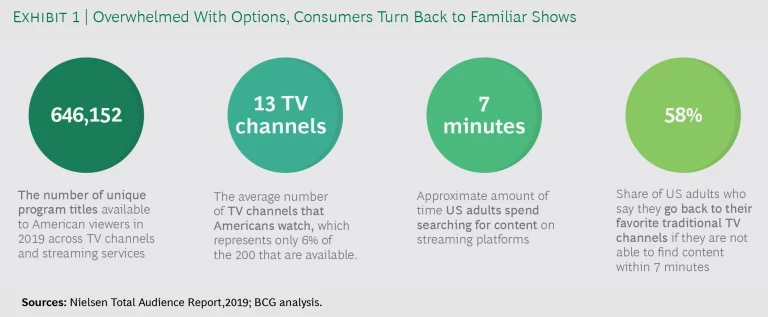

The sheer volume of video content is causing overwhelmed consumers to go back to their favorite traditional TV channels.

The sheer volume of video content is giving signs of overwhelming consumers, who are resorting to known quantities. (See Exhibit 1.) Pre-pandemic (2019) data from Nielsen in the US showed that viewers could choose from more than 600,000 unique program titles offered by TV channels and streaming services. But the average US adult spends only about 7 minutes searching content on streaming platforms, after which 58% said they go back to their favorite traditional TV channels if they are not able to find new content that appeals to them. Our own consumer research during the pandemic found that the big OTT players were gaining disproportionately over niche OTT providers. Of the total number of new OTT subscriptions from December 2019 through April 2020, Netflix had taken 24%, Amazon 16%, Disney+ 15%, and Hulu 14%. While niche services also saw traction, no single service gained more than 5% of the total share.

Profitability pressures are likely to be a continuing problem for all but the biggest or most diversified players. Major OTT companies such as Amazon and Apple can subsidize content cost increases on the backs of other revenue streams, and investors are often more focused on other metrics, such as customer growth, over profitability. For others, though, hit shows that produce continuing revenue streams are harder to come by. Success rates are low and falling. Research by SNL Financial found that from 1991 through 2000 29% of shows on US premium networks, such as HBO, Showtime, and Starz, made it to a sixth season. For shows premiering from 2001 through 2010, this rate of success was 19%. For shows airing from 2010 through 2019, the success rate had dropped to 4%.

One reason is that the original streaming model favored by OTT companies (led by Netflix) prioritizes variety over longevity, which leads to more shows of shorter duration. Original streaming shows have an average lifespan of two seasons compared with four seasons for shows on cable networks and 6.5 seasons for broadcast network programming. Netflix and others often end a show after few seasons to avoid the cost increases that typically take place after the third season and because most streaming shows don’t attract a big enough audience to continue driving subscriptions. OTT providers prefer to maintain continuous pipeline of new content to attract new subscribers.

COVID-19’s Near- and Long-Term Impact

In the short run, the pandemic has both disrupted the availability of event-based programming (such as sports and concerts) and boosted consumer demand for programming of all types. Live sports may be the hardest-hit segment, with major professional leagues truncating or reconfiguring their schedules to try to save some of their seasons. The longer the lockdown, the greater the exposure for the owners of sports rights as more events are canceled and the price of rights comes under pressure as compensation negotiations begin to remunerate buyers for lost sporting events.

For other types of content, the lack of new commissions and production delays will affect program slates for the balance of 2020 and 2021. The delays in production and release could lead to shortages in the near term and oversupply when things return to normal.

Long term, delays in both new movie releases and original content production affects most players. Among subscription services, delays to production are causing new-release shortfalls in the medium term, and long production cycles mean greater exposure to potential content shortages moving into 2021.

Even as production halts cause new content shortfalls, broadcasters continue to experience loss of advertising revenue, which puts added pressure on budgets. Cord cutting linked to consumer economic pressures and the lack of sports hurts cable and other pay-TV providers.

Content Strategies Going Forward

If the bubble does not burst, cost pressures will heighten the importance of well-focused content strategies and business models.

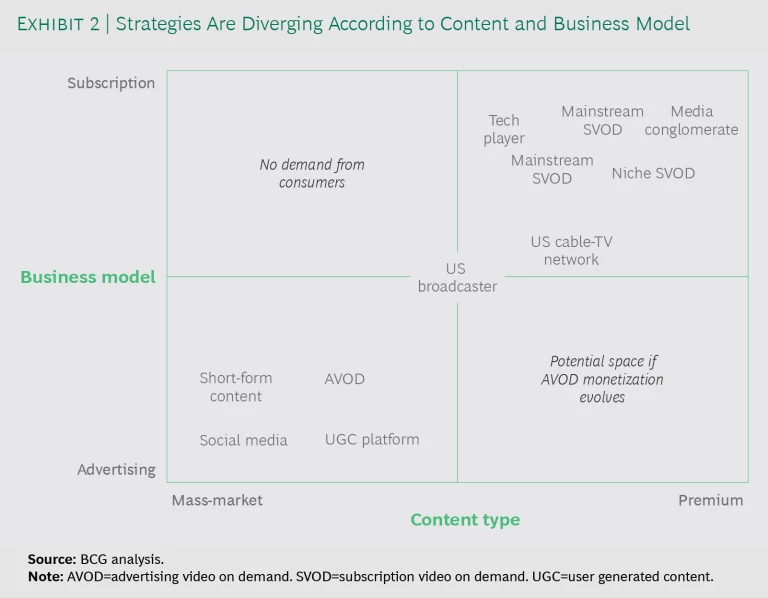

Even before COVID-19, the combination of rising costs and consumers consolidating viewing around a few favorites was leading content buyers to separate into distinct camps according to content type and business model. (See Exhibit 2.) While the pandemic has expanded viewership across all categories, absent a second major wave of the disease, we expect demand to flatten or contract in the next few quarters as people return to work and school and life adapts to a more normal routine. This does not mean the content bubble will burst, however. More likely, it will change shape and size, growing in some areas while shrinking in others, in line with shifting viewer patterns. It is quite possible that the combination of viewer demand and big-player strategies will prevent us from ever reaching peak TV. As a result, cost pressures will continue on most if not all companies and heighten the importance of well-focused content strategies and business models.

Each market will chart its own trajectory, of course, but as the largest single market, the US will set the pace. Here’s a look at the major content categories.

High-End Scripted Film and TV. The heavyweights—Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+, among others—will continue to slug it out. Providing subscribers with a continuous succession of high-quality programming is at the core of their strategies. Costs are unlikely to dip. Going into the pandemic, multiyear deals for top behind-the-camera creative talent involving paydays of $30 million to $100 million a year were increasingly common. Companies need these deals to pay off. Premium programming now has production budgets of $10 million to $15 million per episode (compared with an average of $3 million to $4 million for US cable-TV shows). Viewers have come to expect streaming TV that looks and acts a lot like high-budget Hollywood films. That bar will be hard to bring down. The strong push by deep-pocketed players such as Apple and Warner Media into the high-end market portends an increase in the intensity of the competition that will be great for consumers, albeit tough on the companies involved.

Mass-Market TV. Broadcasters and mass-market cable companies face more intense competition for a shrinking pool advertising dollars. Digital ad spending is expected to increase from 61% of total media spending in 2020 in the US to 71% in 2024, according to Magna Global. Cord cutting will continue. The number of households with pay-TV is forecast to decline from about 83 million to about 73 million, while the number of cord-cutters and “cord-nevers” will increase from 44 million to 56 million over the same period, according to eMarketer. Basic cable networks have been reducing their production of scripted content as it has become too expensive. If an advertising-model provider pays $500,000 to $600,000 for a half-hour episode, with six to eight minutes of advertising time built in, the show requires 2 million to 3 million viewers tuning in regularly in order to break even. These economics are one reason that in 2019, scripted series represented just 24% of the 25 highest-rated original series on cable, down from 50% five years ago.

Sports. Sports has been the last bastion of appointment viewing and is perhaps the category with the most pent-up demand. That said, as live sporting events have returned to TV, haltingly and surrounded by controversy, ratings for professional baseball, basketball, and football have been uneven and generally lower than in 2019. NHL ratings were up, albeit from a smaller base. It’s too early to predict longer-term trends, and few doubt the continuing value of live sports programming to both broadcast and streaming TV, but it may be difficult for leagues and teams to justify the continuing upward-only trajectory in rights pricing.

Short-Form and User-Generated Content. This may be the most dynamic of video categories, in part because of its “social” nature and content that is democratic and anything but curated. Another reason is the ability of a surprise newcomer in the category, such as TikTok, to go from oddity to major market player in the flash of a smartphone screen. Like the marketplace for scripted content, this category is dominated by heavyweight players such as YouTube and Facebook, although well-backed newcomers (such as Quibi) are making a big push for prominence. The market leaders, which had experimented with scripted programming, are returning to their social media and user-generated roots. User-provided and unscripted content, sports and live events, and shows built around personalities and celebrities are likely to dominate. This mix keeps costs low. The category’s popularity with millennials along with the rising use of small-screen devices for streaming should keep viewership levels strong.

Niche TV. Niche players face a struggle for viability, and it’s unlikely that all will survive the shakeout. Our research indicates that much of the post-coronavirus churn will be driven by the simple fact that consumers will not watch as much TV when they return to more regular patterns of activity. More than a third of viewers we surveyed during the COVID-19 crisis said they expect to have less time for television post-pandemic. These numbers suggest that subscribers will make choices about which services to keep, and that as long as they have something they would like to continue watching, they’ll continue to subscribe. This bodes well for providers that have built strong niche franchises around a particular type of programming (such as Acorn TV, Crunchyroll, and Mubi), but more broad-based players that are competing directly with the heavyweight subscription services could be in for a tough ride.

Getting the Mix Right

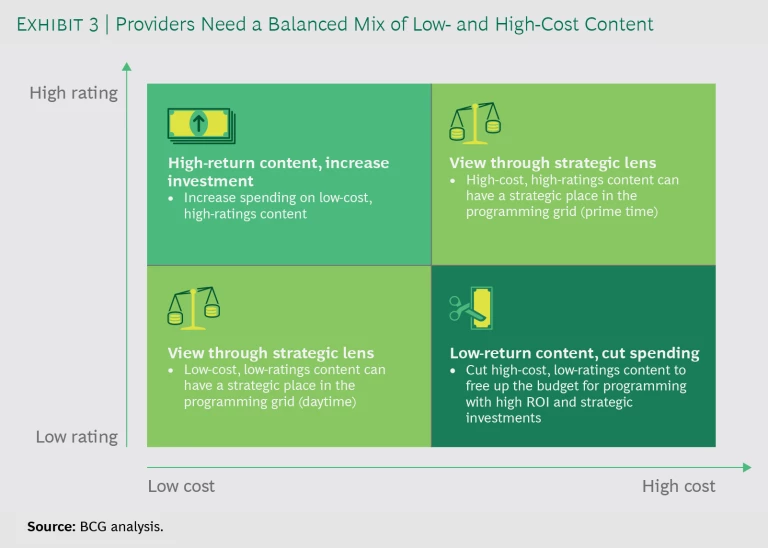

For players in all segments, a critical success factor will be getting the content blend right. This means aligning the mix with strategy and target audiences (such as parents, children, teens, and younger adults) and also striking the optimal balance between cost and high ratings potential. (See Exhibit 3.)

Assuming the bubble does not truly burst, costs will not deflate much, and the need to strike a profitable balance between high- and low-cost content will only increase as penetration rates mature and competition intensifies. Trial and error as well as the ability to make flexible deals and adjust on the fly may also become important corporate capabilities for media companies as the post-pandemic new reality takes shape.