When the pandemic forced schools around the world to close last year, governments in many developing nations had to create a remote learning infrastructure from scratch. The task was especially daunting in countries already struggling to provide education for large, extremely poor populations, such as India—where learning poverty is high and the digital divide remains immense.

Under these difficult circumstances, BCG worked closely with three state governments in India to develop and implement a digital home-schooling program for K-12 students. The initiative revealed significant and persistent challenges for students in households without internet connections, computers, or tablets. But it also offered an intriguing glimpse of the potential for advancing digital education in developing countries—in particular, the possibility of using smartphones as a foundational and low-cost remote learning delivery system.

A Remote Learning Response in India

With the onset of COVID-19, the longstanding disparities in both educational access and digital connectivity were laid bare. Half of the 1.5 billion students affected by school closures worldwide faced economic and technical barriers to online learning, as reported by UNESCO in April 2020—most of them in developing countries. In India alone, the lockdowns affected approximately 250 million students from preschool through high school.

Our strategy was based on three pillars: ensuring student access, providing training for teachers, and promoting parental engagement.

During the initial months of the pandemic, BCG worked with the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) and state governments in Jharkhand, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh to develop a remote learning strategy for 22 million students and 800,000 teachers affected by school closures. Our strategy was based on three pillars: ensuring student access to remote learning resources, providing training and ongoing developmental support to help teachers make the leap to digital instruction, and promoting parental engagement.

The program faced a number of limitations typical of the digital divide. More than 60% of the targeted student population lacked either the necessary equipment or infrastructure to access the digital lessons. Even among the participants, only 20% were able to sustain their remote learning sessions; the remaining students were hampered by factors such as insufficient disposable income to pay for internet charges, electricity shortages, and device quality.

Despite the technical, economic, and social challenges, we saw notable enthusiasm for the digital lessons, especially among those students with smartphone access—and signs of rapid behavioral change, in terms of students’ willingness to adapt to new learning routines and technology, in just in the span of a few weeks.

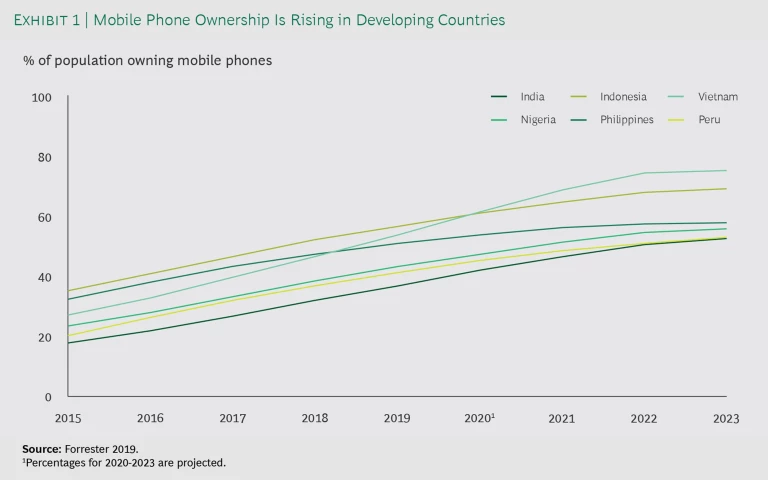

Several other states in India followed our lead with their own initiatives, including Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, both of which replicated the majority of the content from the original program and used many of the same channel strategies. This makes us optimistic about the potential for designing and scaling affordable, smartphone-based digital learning solutions for bottom-of-the-pyramid populations in India and elsewhere. And while the poorest households often don’t own computers or the fastest internet connections, mobile phone ownership is rising fast in developing countries. (See Exhibit 1.)

Based on our experience in the three states, we can offer several key insights:

- Demand for digital learning is high. The program targeted the 4.3 million households in the three states with internet service and smartphones. Within eight weeks, nearly 2 million households signed up. During this period, education content received up to 1.3 million weekly views on YouTube and WhatsApp. As many as 70% of these households were accessing digital education content for the first time, using basic mobile phones that cost less than $70. In some cases, parents who did not have smartphones said they cut back on other household expenditures so they could buy a phone. We saw many inspiring examples of students and teachers who were willing to go to great lengths to participate in the lessons; in one district in Jharkhand, a social worker and a group of schoolchildren trekked 3,000 feet up a mountain each day, just to access the internet.

Other Affordable Ed-Tech Solutions for Developing Countries

The Hole in the Wall Project began in 1999 with an experiment by Sugata Mitra, an education researcher: he and his colleagues stuck an internet-connected computer in a wall of a New Delhi slum and waited to see what would happen. Children in the neighborhood not only flocked to the computer—they taught themselves how to use it. Mitra’s experiment has since grown into a small nonprofit, with 100 computer stations serving poor communities in India and Cambodia.

The mission of eKitabu, a Kenya-based nonprofit founded in 2012, is to deliver low-cost educational content in local languages. Its signature products are e-storybooks for primary school students (Kitabu means “book” in Swahili); it also has a program to train teachers to use its technology in classrooms. The organization partners with digital content designers around the world using a shared internet-based platform, providing digital learning content to over 650 schools in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Open Learning Exchange (OLE), launched in Ghana in 2010, provides free educational resources via its Planet Learning platform, which delivers its content using inexpensive, solar-powered mobile servers; it also offers a cloud-based system for storing user metrics. So far, Planet Learning has contributed to improving learning outcomes for about 50,000 students in over 100 locations, mainly in Africa.

- Multiplatform options expand access and stimulate usage. All three states distributed their educational content through digital and nondigital platforms—not only YouTube, WhatsApp, and other mobile applications, but also television and radio. This multichannel approach helped increase the reach of the program. Several students who did not have access to smartphones or internet connectivity said they used their television to access content. However, students who have a choice between their TV or a digital device largely preferred accessing their lessons through WhatsApp and YouTube, because they could pause and rewind lessons and watch at any time. Daily hourlong sessions for primary school students were also broadcast over the radio, but only 25% of households said they used this option, while 66% said they found content delivery through radio to be either “uninteresting” or “uninformative.”

- Teachers must lead tech adoption. Teachers played a critical role in introducing students to digital learning tools, and in helping them to become active and confident users. But teachers need to be trained and motivated to provide this support. In schools where teachers reached out to their students to offer guidance, by phone or in person, there was a 75% increase in viewership and a fourfold increase in weekly usage of education content. On the flip side, as many as 40% of teachers had low engagement with their students. This led to low student engagement as well, even though these students had access to the same digital education content.

- Quality content matters. Our teams worked with several leading digital content providers to curate a variety of educational offerings, with lessons sorted by grade, subject, and competency. In the process, a few gaps were exposed. For example, the content for secondary school grades was skewed towards science, even though the majority of students were choosing arts and commerce-related material. Furthermore, very limited content existed in local dialects and vernacular language, while primary-grade Hindi and English lessons were too formulaic in nature and not well-suited to language learning. Another interesting insight: as many as 80% of students in Grades 3 to 5 chose remedial lessons rather than grade-level instructional material, which suggests that most students, given the opportunity, will choose the content most appropriate to their learning level.

- Parents are eager co-educators. It was heartening to see how many parents enthusiastically embraced their new role as “co-educators” alongside teachers. Some 80% to 90% of parents said they want the remote learning option to continue once schools reopen.

- Grassroots outreach helps increase parental and student engagement. The visibility of senior political leaders during the program’s kickoff phase—including, for example, a personal message from the ministers of education in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan—was crucial in driving awareness and engagement among parents; advertising and press coverage were also part of the government’s informational outreach. Additionally, program directors held regular video conferences with administrators, teachers, and parents.

- Even the most basic interventions can have measurable impact. While the constraints of the pandemic prevented a comprehensive study of the program’s impact, preliminary data from online quizzes and assessments showed the positive effect of the program, even during lockdown. Over one five-week period, proficiency in literacy and math among students in grades 1 through 8 rose by an average of 6%.

Creating a Robust Digital Education Strategy

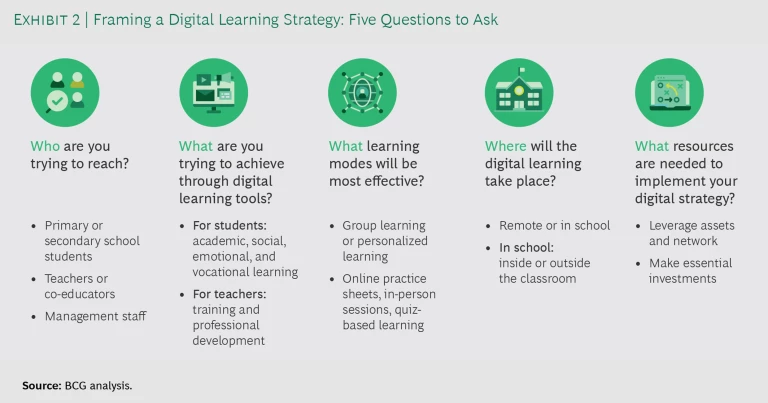

The demand for digital education has never been higher—but meeting that demand will require larger investments, along with a strategic approach and effective implementation. As governments, educators, technology providers, and funders explore the possibilities of ed-tech, we suggest framing any strategic discussions around five questions (see Exhibit 2):

Who are you trying to reach? In an ideal world, governments and educators could meet all the needs of primary and secondary school students, as well as those of teachers, administrators, and parents. With limited resources—specifically time, money, and leadership bandwidth—a digital education strategy needs to prioritize its beneficiaries and its goals. A strategy for early childhood learning, where students have shorter attention spans and greater restrictions on screen time, may not be as impactful as a strategy that focuses on secondary students, whose digital literacy levels are higher, as is their ability to consume and engage with content. Another option could be to focus digital investments on building teacher capabilities.

What are you trying to achieve through digital learning tools? Even within a particular target segment of students or teachers, digital tools can be used to impart many different skills. A high school student could use digital tools to strengthen core content knowledge in math, science, and art, or to develop life skills such as digital and financial literacy—or simply to prepare for exams. These represent unique choices, each of which will influence the devices, content, and delivery modes to be deployed.

What learning modes will be most effective? This a particularly important decision with respect to student needs. Will they benefit from more teacher oversight or more independence? For example, several ed-tech platforms now offer AI-based solutions that allow self-paced, personalized, and adaptive learning. This has several advantages: the ability to access education content anytime and anywhere, the potential of the software to identify learning-level disparities, and the freedom of students to progress at their own pace with limited oversight. Other digital solutions provide supplemental value in the form of explanatory animation and digitized assessment material, prioritizing the role of the teacher as a facilitator.

Whatever the mode of delivery, a full and comprehensive library of content is critical. End-to-end integration of the curriculum—with concept videos, exemplar classroom videos, assessments, and worksheets—encourages active usage in the long run.

Where will the digital learning take place? Once schools reopen, there will be opportunities for digital learning interventions—and innovations—at school and at home. Delivery models for inside and outside the classroom will likely be different, and the pros and cons of each will need to be considered. While at-home education can increase a student’s overall learning time at negligible cost, many students still don’t have a device to use at home. Within schools there is the option of providing devices with screens in classrooms, or creating a separate computer lab.

Limiting devices to a computer lab, however, reduces the exposure time for each student and creates scheduling complexities between classes. One experiment in about 100 schools in India showed that the computer lab-based model reduced learning time for students by 50% because of how long it took the students to move from classroom to the lab and back. A simplified smart-class model within the regular classroom seems to be the better alternative.

What resources are needed to implement your digital strategy? This is foremost about determining the level of financial investment required and identifying the best sources for it. But one should also consider the human resources, team structures, and capabilities that are necessary to make it happen. It is not uncommon to see low-income schools with computer labs that are well stocked but rarely used. Often this is a function of poor implementation. For schools, teachers, and students alike, moving to a blended-learning paradigm is a big shift. Successful investments in infrastructure will also require investments in training, teacher engagement, field-level support, and accountability.

The Affordable Digital Education Path Forward

First-mover models in education are never going to be perfect. Still, what we saw in India during the early months of the pandemic reinforced our belief in the potential of smartphones and other digital technologies as a remote-learning alternative for children in developing countries.

These tools should not be left behind once schools reopen and students return to the classroom. Instead, we should take stock of what we have learned about digital education during COVID-19 and examine how digital technology can continue to improve the experience of students and teachers, both in the classroom and at home. With a better understanding of the costs, choices, and challenges involved, we can reimagine digital learning—and provide an educational lifeline for all children around the world.