Around the world, governments have spoken. To make good on their climate promises, they now need to step up their actions.

As of today, 191 countries have ratified the Paris Climate Agreement, and more than 50% of world GDP is generated by countries that have made net-zero pledges. President Biden has announced that the US will target reducing emissions by 50% or more by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels) on the way to net zero emissions by 2050. The EU plans to be carbon neutral by 2050. China’s president has committed his country to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060.

But getting there will take a lot of work. Annual global emissions of carbon dioxide equivalents amount to about 51 gigatons. We estimate that existing technologies can eliminate about 25% of current emissions, and technologies in early adoption can address another 40%. This leaves approximately 35% of current annual emissions, for which we need new technologies if we are to achieve net zero.

The private sector must do its part, and we recently outlined the mindset change that is required , including looking at companies as providers of solutions rather than only sources of emissions, focusing on new sources of revenue over rising costs, and seeking transformative models rather than incremental improvements. Many companies have announced ambitious climate goals, and more and more are coming to understand that companies can create business advantage and value while accelerating climate action.

In similar fashion, governments can boost economic growth and develop new sources of high-paying jobs with support for what we call climate solution innovation. Climate innovation is a huge opportunity to create value. There is clear evidence that countries can build a sustainable competitive advantage, as China and South Korea did in the last decade with photovoltaic (PV) cells and batteries, respectively. Our research has shown that companies winning in the climate transition deliver superior TSR results, comparable to those of big tech. Winning countries can deliver superior job creation and economic growth.

This article examines how the public sector can accelerate climate innovation efforts.

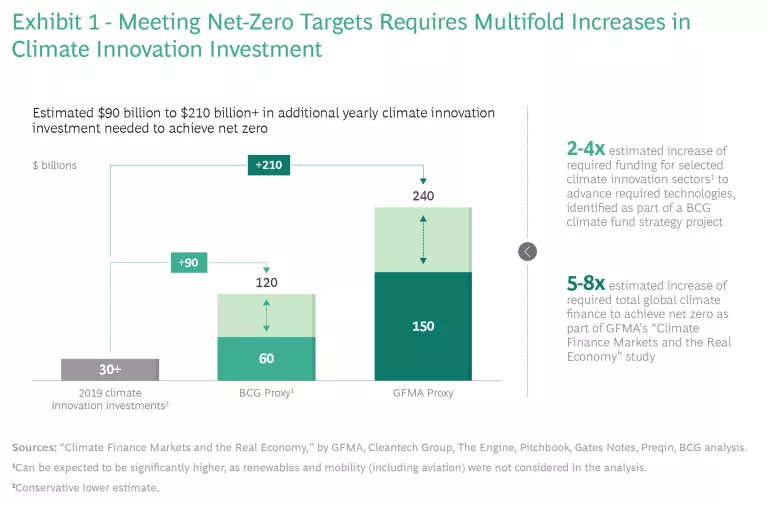

We estimate the world is between $90 billion and $210 billion short of the yearly investments in climate-altering technology needed to achieve net zero.

The Need for Government Action

Venture capital and private equity investments in climate innovation have been growing about 14% a year since 2016, with most of the funding going into mobility, renewables, and waste. Investment totaled about $30 billion in 2019 and $37 billion in 2020. But this is not nearly enough. Separate analyses by BCG and the Global Financial Markets Association (GFMA) on global climate finance requirements lead us to estimate that the world is between $90 billion and $210 billion short of the yearly investments in climate-altering technology needed to achieve net zero. (See Exhibit 1.)

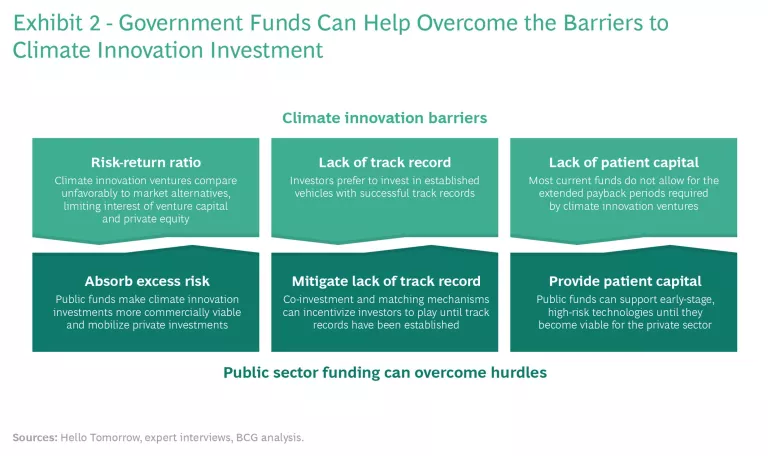

Public funds are needed to meet these targets. The barriers to private investment, which include uncertain returns, lack of a demonstrable track record, and lengthy time frames to payback, are too high for many investors—both the general partners that run venture capital and private equity firms and the limited partners (including many major institutions with fiduciary responsibilities to their investors) that invest in these vehicles. Governments can both bridge the gaps and overcome the ecosystem and investment cycle challenges. (See Exhibit 2.) Plenty of advanced technological R&D requires governments to support and promote basic research while helping build the infrastructure and defining standards needed to undergird a more resilient distributed industrial base. This includes work in technologies that harness nature’s design principles and manufacturing capabilities to design and operate at the atomic level of organic and inorganic matter.

For proof of what governments can achieve, look to the US, where the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) has produced such major technological innovations as the internet and GPS by thinking big and taking chances . Or to China and South Korea. China’s subsidies for photovoltaic technology drove down the cost of solar energy dramatically. PV solar panel costs fell 80% from 2008 to 2013, and global installed PV capacity increased 14-fold from 2010 to 2019. China is now the leading PV producer. South Korea’s investment in battery technology supported key breakthroughs, leading lithium-ion battery costs to drop nearly 90% from 2010 to 2019. South Korean battery producers took a leading market share in 2013.

Public funding via co-investment and matching mechanisms helps lower risk perception and mobilize increasing venture capital and private equity investments in climate innovation. Patient public funding can help close current funding gaps by compensating for the impatience of private capital for extended payback cycles and lengthy public funding processes.

The Roles for Climate Innovation Funds

For all of these reasons, both companies and governments have started investing in climate innovation funds, which are gaining traction globally. The EU, for example, has launched a €10 billion climate fund “for the commercial demonstration of innovative low-carbon technologies, aiming to bring to the market industrial solutions to decarbonize Europe and support its transition to climate neutrality.” Microsoft’s climate innovate fund will “will primarily invest in climate solutions that have been developed and need capital to scale in the market.” Leading tech companies (such as Amazon), industry associations (Oil and Gas Climate Initiative), and governments (Japan, Germany, and the US) have launched or announced capital commitments for climate innovation funds that will invest in and support the next generation of climate focused start-ups on their paths to net-zero targets.

Leading tech companies, industry associations, and governments have announced capital commitments for climate innovation funds that will invest in the next generation of climate focused start-ups.

The climate investment cycle includes three broad phases: research and development, validation and early deployment, and large-scale deployment. In our experience, public sector entities can best support the investment ecosystem during each stage with funding mechanisms designed specifically to help close cycle funding gaps without interfering with market dynamics.

In the first phase, mission-driven R&D grant programs with a clear and focused strategy and lean processes can provide a critical push. Multiple programs already established by governments globally focus on innovation, some with climate specific objectives. These include the EU’s climate innovation fund and the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR), and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs in the US. These R&D-stage funds tend to focus on climate impact through grant instruments with little or no consideration of financial returns. This approach allows for mission-driven investment decisions and higher risk absorption. It is primarily practical in areas with limited or no private sector funding and limited participation from other existing public sector mechanisms.

Funding in the second stage—validation and early deployment—typically involves public-private partnerships or co-investment with venture capital and private equity funds to increase the money available for high-impact, high-risk companies. Multiple public-private partnerships and early-stage co-investment mechanisms are at work globally, and they balance consideration of climate impact and a desired financial return from investments, typically focusing on both debt and equity. They include the National Research Foundation of the Singapore prime minister’s office and the European Investment Fund. No climate-specific vehicles have yet been established, perhaps because balancing risk profiles and financial returns can be challenging.

In the growth funding third stage, governments can offer matching grants that amplify the impact of private investors in support of large-scale deployment, thereby incentivizing institutional investors and corporations to put money into climate innovation funds. A limited number of these matching facilities have been established globally and include the Korea Venture Investment Corp. and British Business Investments. Most recently, Germany’s Zukunftsfonds has said it plans to invest more than $10 billion and mobilize three to five times that sum in private capital dedicated to advancing future technologies. All of these funds ensure high commercial viability for projects, but they have limited ability to invest in high-risk, forward-looking technologies, and they tend to exclude investments that have a payback beyond the traditional fund cycle.

A Plan to Target Funding

We all know that simply throwing money at a problem is rarely effective. Before they ramp up climate innovation investments, governments need well thought out goals and a roadmap for achieving them. Here’s how they can plan for targeting funding.

Before they ramp up climate innovation investments, governments need well thought out goals and a roadmap for achieving them.

First, governments should adopt a mission-driven approach to climate investment. This means adhering to four requirements:

- Missions should be well defined. Investments should be based on detailed definitions of technological challenges, goals and deliverables, including processes for monitoring and accountability.

- Missions should comprise a portfolio of R&D or innovation projects for each technology challenge. R&D (especially early-stage) is highly uncertain and requires policymakers to accept failures and use them as learning experiences without punishing stakeholders for defeats derived from good-faith efforts.

- Missions should result in investment across sectors and involve different types of actors. The highest impact can be achieved only if funds focus on actors across an entire economy and ecosystem, not just one sector or ventures limited to the private or public realm.

- Missions require integrated policymaking. Priorities need to be translated into concrete policy instruments and actions carried out at all levels of the public institutions involved, with a clear and strategic division of labor among them.

Using a mission-driven approach, governments should assess their domestic climate innovation needs. Governments can then select investment areas by analyzing available opportunities based on their impact (financial and climate), policy or regulatory tailwinds, and market attractiveness (technology maturity, funding gaps, and general barriers).

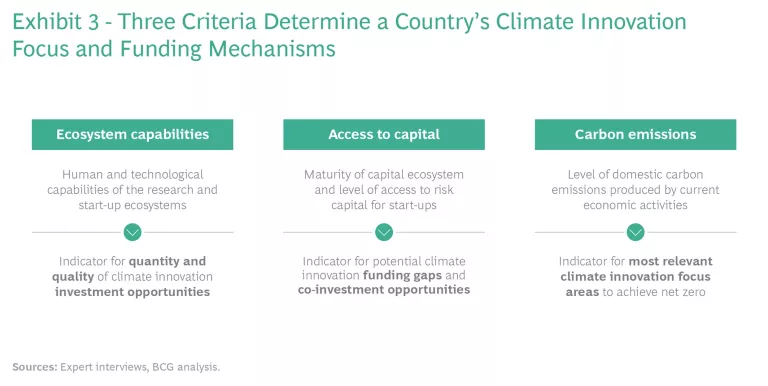

The level of need is guided by three main criteria. (See Exhibit 3.) The first is the current state of the country’s climate innovation ecosystem—the human and technological capabilities of its research institutions and start-up ventures. This serves as an indicator for the quantity and quality of climate innovation investment opportunities. Next comes access to capital, an indicator for potential climate innovation funding gaps and co-investment opportunities. Third is the level of domestic carbon emissions produced by current economic activities, which points to the most pressing areas of focus.

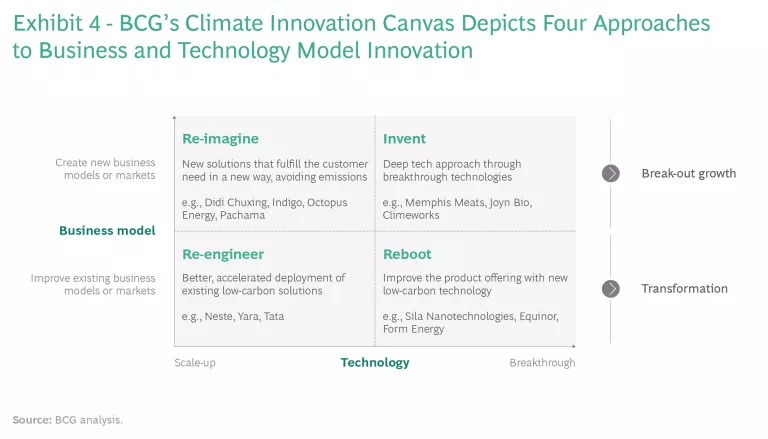

In our analysis of how the private sector can most effectively pursue climate innovation opportunities, we developed a matrix of four areas of effort, which we call the climate innovation solutions canvas. (See Exhibit 4.) Combining the canvas with the three country criteria provides a means for governments to target their climate investments. For example, large industrial nations, which have the most relevant options, need new technologies, including high-risk breakthrough approaches. This points their investments toward backing the invent and reboot quadrants of the canvas. They can also provide funding and ecosystem support for scaling up technologies in the re-imagine and re-engineer categories, prioritizing the most promising investment opportunities.

Emerging industrial nations will also want to fund development of new technologies (invent and reboot), but a lack of existing capabilities may limit their investment opportunities. On the other hand, large domestic markets provide great opportunities to explore and fund the scale-up of existing technologies (re-imagine and re-engineer).

Smaller economies with skilled workforces can leverage their capabilities to drive development of new technologies (invent and reboot) in priority sectors, but they will likely provide only select funding to scaling technologies that focus on new business models, such as ride hailing, to reinvent markets.

Other types of economies, such as developing industrial nations or countries with large fossil fuel industries, can conduct similar types of analyses.

Six Success Factors

Planning is one thing. Execution is another. Here are six key success factors that governments can apply to monitor their progress in creating and managing climate innovation funds:

Governments should carve out a complementary market role that focuses investments on underserved segments to mobilize private capital and avoid direct competition with private investments.

- Set a clear climate impact investment focus that concentrates efforts on select investment areas to further develop internal capabilities and create multiplier effects in the portfolio.

- Carve out a complementary market role that focuses investments on underserved segments to mobilize private capital and avoid direct competition with private investments.

- Coordinate fund activities and public policy to provide the required demand-side stimulus (“tailwinds”) via policies and regulations (such as carbon credits and green procurement).

- Build an experienced team with a demonstrable track record, in impact and commercial investing, with in-depth climate tech expertise and a strong partner network to drive portfolio value creation.

- Provide transparency by reporting impact, with highly visible communication and engagement efforts that create convincing proof points.

- Establish a strong and recognizable brand that signals commitment to climate innovation and to being an attractive co-investor for private-sector funds.

We all know that the climate clock is not on our side. Not only does the planet continue to warm, but the technologies that could ultimately turn the tide require years of R&D before they enter the mainstream. More money is a big part of the solution, but the funds must be well targeted and effectively invested. Governments that want to have an impact—and reap the accompanying economic benefits—will start to develop their climate innovation funding plans now.

The authors are grateful to the following for their input and assistance: Vinay Shandal, Veronica Chau, Greg Fischer, Eelke Kraak, Pol-Herve Floch, Tariq Nanji, and Smith Sangiambut of BCG; Massimo Portincaso of Hello Tomorrow; Andre Loesekrug-Pietri of Joint European Disruptive Initiative (JEDI), and Dennis Pamlin of Mission Innovation.