The Keys to Successful Transformation

In the rapidly changing markets of Greater China, disruption is always around the corner. Companies in every industry need to be prepared to continually reinvent themselves to remain competitive. Transforming a company can require a variety of strategic moves: introducing an entirely new product line, changing the business model or closing down entire business lines, overhauling the brand image, improving operations, reshaping the corporate culture—or all of these elements.

The decision to transform is not a guarantee of success, however. BCG research has found that globally, 75% of corporate transformation programs fail to improve the companies’ short- or long-term ability to create value.

BCG recently examined the record of value creation among large companies in Greater China. We looked across industries, at both public and privately-held businesses, examining those that experienced a significant decline in revenue, profit margin, and/or market capitalization in the past decade yet then developed a transformation strategy that put them on the path to a clear rebound.

In this report, we look at five of these transformation heroes—tech giant Alibaba, state-owned insurer CPIC, auto manufacturer Geely, tech company Acer, and privately-owned apparel company Semir—and how they each set about reinventing their existing business in ways that continue to increase their value. Taking into consideration their stories and our research and experience working with hundreds of additional companies, we’ve identified five critical elements of a successful turnaround.

1. Attack the Status Quo, Aggressively and Constantly. When China’s overall GDP was growing by double digits, most companies were able to achieve strong growth and robust profitability with or without the best business model. As the market has matured and become more complex, however, constant self-examination has become key to success. Companies find that they have to be highly proactive, anticipating challenges ahead. Many players have initiated transformation strategies even without facing a crisis because they recognize that market trends are changing, and they must adapt. Our research found that companies that transformed preemptively created value, reflected in total shareholder return (TSR) that, on average, was 6% higher over a three-year period than the TSR of companies that transformed reactively. Amidst rapid shifts in the market, speed and efficiency make a big difference. Those that succeed at transformation view it as a continuous journey; being prepared to meet constant change head-on becomes a way of life.

2. Be Strategically Focused on Ways to Win in a Changing Market. China’s economy has shifted in the past ten years from “growth in quantity” to “growth in quality.” As a result, companies that push products and services onto the market without establishing clear differentiators will be left behind. According to BCG's research, the companies that have gone through trans- formations with a long-term strategy outperformed those with poorly-defined strategic plans. Many turnaround players have redefined their value proposition from “affordable” to “brand equity focused” to attract a more upscale domestic consumer and expand globally. To compete today, players must identify where they can win, mapping all market segments and determining which parts of the business have the core competencies that will provide a competitive advantage. Moreover, business leaders must be prepared to explain all steps of the strategy to employees and investors. Often, they must terminate or divest unprofitable business even if it causes a short-term hit, then take action to acquire and/ or invest in new businesses. All stakeholders need to be aligned on strategy to win in the medium- and long-term.

3. Drive Both Growth and Operational Excellence. A successful transformation strategy requires a deep examination of the value proposition that existing backend functions such as IT, HR, and operations teams provide. Operational excellence, especially when enhanced by strong digital capabilities, plays a key role in deliver- ing quick results. That is because a company that has developed operational excellence will be in a position to assure that it can fund the transformation journey from the early stages to its conclusion and will be able to build a foundation for sustainable growth.

Strategic changes to capture growth generally require alterations to the operating model to achieve enhanced performance that is sustainable over many years. Investment in R&D and innovation is essential to winning in the long run. Our analysis found that during transformations, companies with above-average R&D spending deliver about 5 percentage points more in TSR than those with below-average R&D spending.

In the last two global downturns, the most successful companies were diligent about pursuing operational efficiencies, thereby improving their profit margins. But revenue growth was the largest driver of their performance, accounting for nearly 50% of TSR, or twice the impact from cost reductions.

4. Shape the Organization and Culture. The way a corporation is organized has a powerful effect on its products, services, customer relations, brand, and every other rung of the value chain. If management transforms the value proposition, the entire organizational structure and talent pool needs to be in sync with the new strategy—an outdated corporate culture cannot compete in a changing market. It is often necessary to restructure, sometimes with new teams. However, a comprehensive strategy for top-down communication, along with relevant training, can instill a new culture and mindset in the organization.

5. Manage a Program, Not Multiple Projects. “One goal, one program” is integral to facilitating a successful transformation. A company’s leaders need to direct their actions at restructuring the business as a whole instead of simply adjusting to changes. Our research showed that formalized large transformation programs outperformed smaller-scale efforts by an average of 5% in annual TSR in a five-year window.

It is important that the entire organization is vested in the program. An efficient communication plan and incentive program are key to engaging employees in the transformation and showing them how they can help make the outcome successful. There should be a transformation management office (TMO), staffed by full-time employees. The TMO role is to create a customized transformation infrastructure and milestone-tracking mechanism that will facilitate the transformation and ensure that results are deliverable. At the same time, corporate leaders should be prepared to keep the orga- nization apprised of progress through continuous top-down communication, reiterating that this is an ongoing, organization-wide program.

The stories that follow illustrate how strong corporate leaders with determined visions have embraced the five elements identified and become transformation heroes, turning around large companies facing high-stakes changes. These measures have led to dramatic improvements in performance and market share, and created substantial value for shareholders. Their stories can instruct and in- spire other companies that are facing disruptive changes or anticipate the need to begin a turnaround journey.

Alibaba Change Is the Only Constant for Growth

Alibaba Group is China's biggest e-commerce company and one of the world’s most valuable tech companies, with a market capitalization of about $590 billion and revenues of 549 billion RMB in the 12 months ending June 2020. Jack Ma, who founded the company with 17 friends in 1999 and ran the company until he stepped down as executive chairman in 2019, has become one of China’s most high-profile business leaders.

Although Alibaba and its exponential rise are wellknown around the world, one of the foremost factors in the company’s growth is its continuous transformation, which people rarely notice. Alibaba continually adapts its organizational structure to its business development to keep up with each stage of growth. Ma learned about the need to evolve along with the market early on, when the internet bubble burst just two years after Alibaba started, and he had to cut back temporarily on his ambitions to run an international company. Since then, viewing change as the only constant has become one of the core values of Alibaba. “Transformation is painful,” Ma wrote in an open letter to his employees, “If we don’t change, we won’t even have the chance to suffer in the future.”

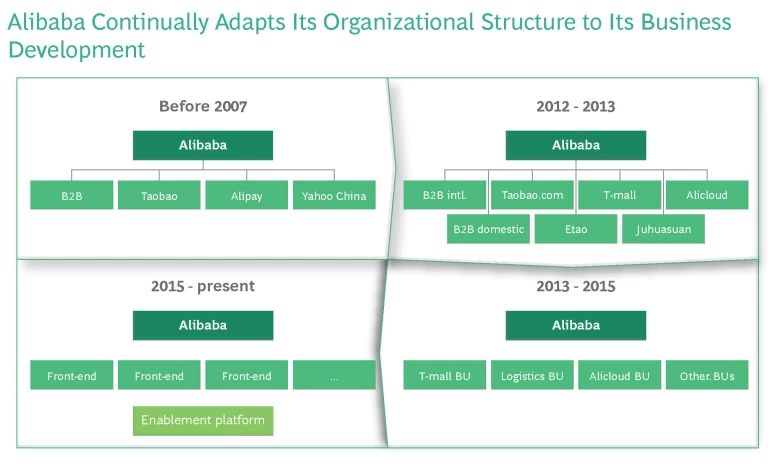

Alibaba’s most significant changes, however, came in two distinct waves of transformation. In the first, it refined its organizational structure by splitting its various lines of business into vertical units to address customer needs in a timelier fashion. In the second wave, due to Alibaba’s growth into a large and complex organization, the need to maximize synergies from within the Alibaba Group to build a nonreplicable competitive advantage was realized. Therefore, they reorganized into a “digital economy” with an enablement platform to serve all businesses on its platforms.

Wave 1: Vertical Segmentation to Address Customer Needs, Before 2015

By 2007 Alibaba was well on its way to becoming a tech giant, operating through its B2C/C2C subsidiary Taobao, its B2B subsidiary Alibaba.com, Alipay, and Yahoo! China. As the growth cycle continued, Alibaba’s management saw a need to separate into specialized business units in which managers would be close to the frontline and able to respond to distinct customer needs and make decisions quickly.

Phase 1: From 4 Subsidiaries to 7 Business Groups, Between 2007 and 2012

As the company embarked on its fastest growth trajectory ever, Alibaba began splitting its business into vertical units. Between 2007 and 2012, it restructured its four subsidiaries into seven business groups. The segmentation into separate business groups helped resolve several challenges that resulted from growth.

In the first place, the organization was becoming more complex, which meant it was experiencing hurdles to efficiency that had the potential to limit future development. Additionally, new B2C and C2C business opportunities were emerging. As growth came from a strategic expansion in B2C commerce through Taobao, customer bases also grew increasingly diversified. Each of these customer groups had its own needs that could not be served by Taobao alone. Nor did the existing setup lend itself to the needs of global customers at a time when the company was embarking on a new global strategy.

In the transformation, Taobao was split into four separate groups: the C2C business Taobao.com, the search engine etao, the B2C unit T-mall, and the sales and digital marketing platform Juhuasuan. The B2B e-commerce business, Alibaba.com, was spun off into international and domestic units. Due to the distinctive nature, the cloud computing platform Alibaba Cloud remained as a new, separate business group. Each business group had its own group leaders who had full decision-making power and the responsibility to grow their respective businesses.

Phase 2: From 7 Business Groups to 25 Business Units, Between 2013 and 2015

As Alibaba continued to grow across industries and become ever more complex, the group saw the need to transform the organization setup again to timely address the rising volume of business questions and interact more closely with customers to make the most informed decisions.

As a result, Alibaba again restructured its operations, this time into 25 business units. This split, aimed at meeting a larger volume of customer needs and market changes through efficient decision-making, represented a critical transition from the purely vertical play of Wave 1 to a platform structure, which would become the organizational foundation of Wave 2.

During the 2013 transformation phase, Alibaba split a number of its divisions into horizontal units—for example, Alibaba Cloud and the logistics business—but otherwise left intact the core rationale of having each business unit function autonomously with sole responsibility for its growth and development.

The 25 business units were similar to the previous structure of seven business groups when it came to actual operations. There were, however, two key differences.

First, the decision-making power was decentralized further in the new units, so unit leaders had autonomy when it came to resource allocation and decision-making. With this structure, unit leaders were at the forefront again and able to provide better customer interaction and faster responses to market needs.

Second, Alibaba appointed nine executives to a new strategy management and operations committee. The committee’s role was to oversee and coordinate day-to-day businesses to ensure that business unit strategies were aligned with the Alibaba Group’s direction. Eventually, the executives formed another committee to look for synergies within the group.

Wave 2: Leveraging Group Synergies to Strengthen Core Competitive Advantage, from 2015 to Present Day

As the company grew even larger, the advantages of capturing synergies within the group became evident. It became increasingly clear that the siloed nature of the 25 business units was leading to redundancies in the workflow and inefficiencies in the use of resources. The setup was not efficient enough in fostering innovation—for example, customer data was scattered throughout the organization, with no single source that might provide insights and incentives for innovation.

Thus, Alibaba entered Wave 2 of its transformation, restructuring so that all lines of business can now reap value from the vast ecosystem that the organization has become. The company has found a core, nonreplicable competitive advantage in its ability to leverage Alibaba Group synergies.

Instead of multiple vertical business units, Alibaba now connects all of its businesses to a modular platform. At the front-end, business groups are still separated according to their function—for example, there are groups for e-commerce, financial services, cloud computing, and the other business lines, each set up with the ability to operate as an agile structure that can quickly react to market changes. However, backend functions are carried out through an enablement platform that provides services such as membership enrollment and product management to all businesses.

The enablement platform is able to generate useful insights for front-end use throughout the organization. Any business can tap into the analytics to offer value-added services to clients—for example, insights on common problems in the small- to medium-sized enterprise sector or case studies on management best practices.

The platform also streamlines new business rollouts, thereby facilitating further expansion. In 2016, when Alibaba launched Hema Fresh, its venture into “New Retail” through a supermarket chain that offers online and offline shopping, Hema had instant access to membership management, merchandise display, shopping cart management, e-payments, and inventory from all of Alibaba’s digital infrastructures. “Without the strong platform enabled by multiple businesses, Hema would have taken at least 24 months to build its operational and servicing capabilities. Instead, we were able to get all things done in nine months," Yi Hou, the CEO of Hema Fresh, has

Ma has told his employees and investors that the right balance of system, people, and culture is critical to achieving long-term sustainable growth. Alibaba now holds 80% of China’s e-commerce market share and has a global workforce of more than 100,000, but continues to engage in the self-reflection and creative solutions that have made it a force for growth.

CPIC A Large Enterprise that Keeps Adapting

Founded in 1991, China Pacific Insurance Company (CPIC) is the third largest insurance provider in China. On the eve of its 30th anniversary, CPIC has demonstrated its forward-thinking vision in adapting to the technology disruptions of the 21st century and China's increasingly sophisticated consumer market. In recent years, CPIC has been highly proactive in transforming its business in order to stay one step ahead of a rapidly changing industry—even though it has been difficult to transform a large SOE in a business that is tightly regulated. Some commentators have called CPIC “an elephant with a young mind” because it is large yet highly adaptable.

Since 2011, CPIC has embarked on a strategic transformation—later called “Transformation 1.0”—even though the company was not facing a full-blown crisis. To push the transformation forward, CPIC closely analyzed its weak spots and challenged itself to push for excellence.

In 2011, CPIC’s revenue growth slowed, though it still achieved a reasonably healthy 10% growth and its profit margin remained stable at 5.5%. The Chinese insurance market was at a turning point, however; Domestic consumers were becoming increasingly savvy, and buying patterns and expectations were also changing. In response, the company focused on value creation in its high-level strategy and invested more resources into high-value channels such as individual insurance. The results were dramatic: between 2011 and 2016, new business increased by 184%, and the company's share price rose by 75%.

However, CPIC was not satisfied with performance that was simply “good”. Its management recognized that greater change was on the horizon and that the company's business model would need to adapt. The industry could no longer rely on investment-based growth, so CPIC went back to its original purpose of risk protection, but with stronger risk regulation. Seeing the rise of the Fintech market, CPIC’s management also recognized the importance of data and advanced technologies.

In 2017, Kong Qingwei was appointed chairman and executive director of CPIC and prioritized deepening the company's transformation. Though Transformation 1.0 had been a success, Mr. Kong was determined to push forward with a strategic campaign to assure that CPIC would remain a top performer as the insurance industry continued to evolve.

During “Transformation 2.0”, which CPIC expects to complete in 2021, the key objective is to adapt to the changing consumer market and regulatory environment. The company is embracing technology innovation and enhancing its approach to talent acquisition. It is promoting synergies across different business lines—an effort that requires cultural change along with collaboration mechanisms— and developing businesses relating to high-quality lifestyle services, including elderly care and health care services.

CPIC is driving Transformation 2.0 via five major levers:

- Talent. CPIC has realized that transformation requires fresh thinking and new kinds of expertise and, therefore, it is actively recruiting young talent to foster a culture of innovation. The company has also set up a strategic workforce planning initiative to identify the capabilities its internal and external sales teams will need for the future. Moreover, CPIC is putting into place more flexible and market-oriented incentives to boost innovation further. To build capabilities that will support sustainable growth, CPIC launched a long-term incentive and restraint mechanism (Longevity Program) for key talents by combining its strengths as an SOE with market factors. In order to share the benefits of the company's growth appropriately, the mechanism targets those who create value, incentivizes incremental sales, and links the benefits an employee receives to their performance by benchmarking against the market, systems, the budget, and historical data. It also advocates bold innovation and motivates the organization to strive for the best and build a talent management system aligned with the market. This system will safeguard CPIC's transformation in the long-term and guide the healthy development of the insurance sector.

- Digital. By overhauling its IT system, CPIC will significantly increase the number of requests it can respond to every second and at any one time, thereby improving its customer service capabilities. It will optimize tools to facilitate and manage internal/external sales teams, and build a unified group-level big data platform that connects customer and business data from subsidiaries, so as to uncover greater value from its customers. The platform, with its unified account system for over 100 million customers, has broken down customer data silos and optimized digital customer sharing. So far, it has handled over 110 million queries, effectively supporting customer management and resource sharing.

- Synergy. CPIC set up a synergy development center at the group headquarters to coordinate resource allocation across subsidiaries, and built a data sharing system across channels to make its service more customer-centric. Meanwhile, its subsidiaries have formalized the collaboration into their daily work and incentives to enhance their integrated service capabilities for big businesses.

- Governance. CPIC set up nine centers at its group headquarters to achieve two major purposes: the first is to enhance vertical management across business lines and maintain consistency of group-wide financial and risk management standards; the second is to push standardization across frontline organizations, invest more resources, and improve sales capabilities.

- Ecosystem. CPIC has stepped up investments in new business fields in recent years, based on its judgment of industry trends. The company aims to build a complete ecosystem offering quality services that address the needs of target consumers. For example, CPIC partnered with leading elderly care provider ORPEA to build high-end communities for senior citizens, introducing services of a global standard to serve high-end customers. In addition, it launched a “blue book” with concierge health-related services, including in-house doctors, access to top specialists, and priority hospital services. CPIC moved a step forward to partner with leading capital and health care providers to build internet-connected hospitals, offering integrated online to offline medical solutions to customers. It has also participated in health care investment funds to seek opportunities in medical services, MedTech, medical devices, and health management sectors to diversify its capabilities. ( See the sidebar “Additional Areas of Transformation”).

Additional Areas of Transformation

- Auto insurance: Pursue new growth drivers and improve renewal rates. Facing challenges such as falling new car sales and continued reforms across the automobile sector, CPIC started to improve its customer operation capabilities to shift toward quality growth. In recent years, the company has successfully grown through new digital channels, technology enablement, and lean claim handling operations.

- Agricultural insurance: Pursue innovative products and technologies to improve market position. CPIC has played an active role in serving China’s strategic agriculture and rural insurance needs. The company has formed an industry-leading system of risk protection products, along with a digital operations and management system for agricultural insurance (such as the “e-nongxian” digital tool), through innovative products and technologies, significantly improving its basic management capabilities and agricultural insurance specialization. The company is also working in cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences to explore new ways to grow the agricultural insurance business sustainably. It ranked third in China’s agricultural insurance market in 2019, with more than 10% of total market share, a rise of almost 3% since 2017.

- The emergence of the “product + service” model of enhanced customer management capabilities. High-end “CPIC Home” retirement communities are gaining traction, with locations in Chengdu, Dali, Hang- zhou, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Xiamen. As of 2019, the company has issued nearly 8,000 move-in notification letters to qualifying customers, thereby enhancing its operations of high-end customers. “CPIC Blue Passport,” a program at the core of CPIC’s health service network, has nearly eight million customers and covers more than 2,800 health care providers in China, almost 50% of which are Class IIIA hospitals. The program is gradually expanding to high-end health care services, including health counseling, advanced payment for hospital treatment, fast track for critical illnesses, online diagnosis, specialist health checkups, premium claim handling, and genetic screening.

- “Responsibility, intelligence, and warmth”—building a “CPIC Service” brand. CPIC is committed to customer-centric transformation. As China's insurance market opens up, CPIC has prioritized quality service to deliver performance above its peers, address cross-sector competition, and manage quality growth. It is actively building its service brand and improving the quality. The company set four major targets: “enhance the overall service level; improve the speed and efficiency of smart service; deliver first-class customer experiences; and steadily increase service value.” It has launched initiatives in service and product innovation, technology application, ecosystem building, customer experience management, and brand communications in an effort to build a brand of “responsibility, intelligence, and warmth”. CPIC’s Property & Casualty and Life Insurance businesses have received the highest AA ratings by regulators for three consecutive years. The “CPIC Service” brand has been recognized by regulators, the market, and customers, and the company's competitiveness has continued to rise.

In its second transformation, CPIC carried over some lessons learned from Transformation 1.0, such as the importance of creating a cohesive infrastructure to facilitate the rollout of new transformation projects. The company has addressed this by establishing so-called “clusters of projects” with high synergies and correlations that are directly managed by the group or subsidiary leadership.

The senior leaders set project KPIs for each cluster and are responsible for the outcome. Frontline workers are motivated to help the transformation succeed because, with the strategic direction coming directly from the top, they know the results will be valued.

Moreover, CPIC’s leaders understand that the second transformation will achieve the greatest success if each of the company’s 100,000 employees feel that they can play a role in it, sharing both the responsibility and the rewards. Therefore, CPIC has mobilized employees across the company and shared information about Transformation 2.0 on internal platforms. Success in the transformation has been linked to performance reviews to motivate employees. The results so far have been remarkable. The changes created through transformation have helped to reshape employ- ees’ values. It is becoming a shared mission among all employees to address customer needs through continued product, service, and risk management innovations, as well as optimization of the customer experience.

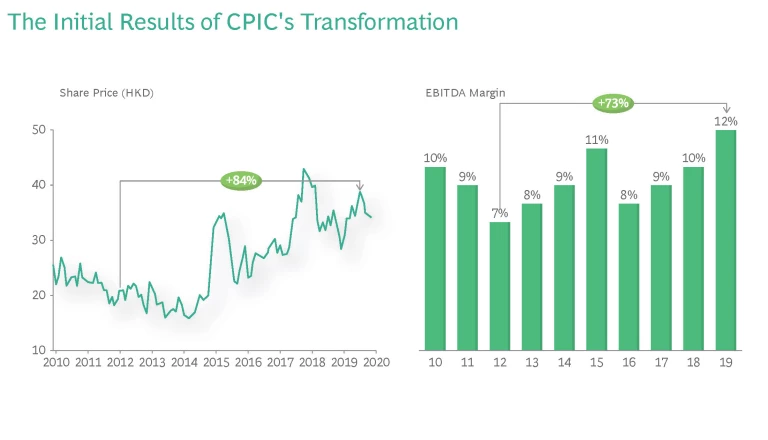

The initial results of the transformation indicate that CPIC is continuing on the right track. In 2018, CPIC Group revenues rose to $53 billion—more than double what they were in 2011. Insurance revenue also grew 14.3% and profit increased 22.9%, while CPIC's EBITDA margin improved by 2% compared to 2017.

In 2019, Insurance Business magazine rated CPIC number six among the world’s most valuable insurance brands. CPIC’s customer-centricity, cross-selling, and wider ecosystem have generated a revenue boost, while the bottom-line organizational changes have improved efficiency and profitability.

Geely Rebuilding Through Bold Innovation

Geely is now the third largest car manufacturer in China and the 17th best-selling brand globally. Its success has been the result of an eight-year transformation journey; once known strictly as a manufacturer of low-end compact cars for the Chinese market, Geely has reinvented itself as a technology-driven global player.

When Geely first started in 1986, it was a family business that made refrigerator components. However, Li Shufu, Geely's founder and CEO, has always run the business with a forward-looking vision, and he realized early on that the automotive industry was going to play a fundamental role in the growth of China’s manufacturing sector.

In the 1990s, Geely transitioned into making motorcycles, then affordable automobiles. In 2005, Geely became China’s first private sector automaker to be listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Yet in 2007, Geely’s domestic market share dropped to 2.9%, down from 3.4% during the two previous years. The reason seemed clear: with China’s rapid growth, many consumers were demanding higher quality automobiles.

Automobile sales in China had risen about 24% annually over the decade but accompanying the growth of consumer purchasing power was a more demanding customer market. Car buyers were gravitating toward higher quality models, whereas the general perception of Geely was that its cars were of a lesser quality and possibly unsafe, with limited ability to innovate.

As Geely’s management saw it, the company would have to transform its product lineup and image. While Geely had no more than 0.4% global market share as of 2005, driven by sales made in China, the company’s managers determined that it was time to build an international presence. Moreover, they were determined to create a reputation for making the world’s safest, most environmental-friendly and energy-efficient cars.

The Strategy for Transformation Consisted of Four Main Pillars:

- Branding Strategy. The first and most impactful pillar was a branding strategy aimed at growing organically from within. To change the company’s "cheap and low-quality" image, Geely’s management made a bold decision to halt production of three of its best-selling low-end models—Haoqing, Meiri, and Youliou—and replace them with more sophisticated models—the Geely KingKong family sedan, the Free Cruiser economy sedan, and the Vision mid-end sedan. Once the new models were on the market, Geely temporarily spun them off into three separate brands, each functioning as a separate business unit. The idea was to distance these new upscale models from the “mother brand,” the old Geely name, until consumers became more accustomed to a new kind of made-in-China car.

To build its reputation as a technology-driven automaker, Geely presented 23 high-tech vehicle prototypes at the 2008 Auto China car show, including the GT Concept model, which showcased Chairman Li Shufu’s ambition to make Geely the Rolls Royce of China.

By 2014, Geely’s new models were becoming better known. The multibrand strategy had been successful in elevating the company’s image, but the strategy itself required supporting separate facilities that could operate more efficiently under one roof, so it was time to reunite the sub-brands under a "One Geely" brand. This way, Geely was able to centralize its R&D and marketing activities, optimize its distribution channels, facilitate a coordinated growth strategy across all markets, achieve better economies of scale, and keep attention focused on the mother brand.

- Strategic M&As and Partnerships. The second of the pillars was a form of inorganic growth; an aggressive pursuit of highly strategic M&As and partnerships that would provide a shortcut to an international presence. The most high-profile of these deals was Geely’s 2010 acquisition of the Swedish multinational Volvo—an automaker long-renowned for safety and exceptional engineering and craftsmanship. With the acquisition, Geely became China’s first global automotive group, inheriting all of Volvo’s patents, product platforms, production facilities, and engineers, as well as more than 2,000 sales offices in 100 countries. Catching the public by surprise, Geely adopted a hands-off management style by retaining Volvo’s engineering and technology talent and management style and giving the company free rein to develop new products. After ten years of independent operations, Geely announced preliminary plans to merge with Volvo with the goal of sharing resources and knowledge, strengthening the group’s market position.

Another notable acquisition was London Taxis. Geely had already bought 20% stake in the British taxi maker in 2006, when it began producing vehicles at its factory in Shanghai, but it acquired the parent company in 2013, gaining all of London Taxi’s plants, property and equipment, intellectual property rights, trademarks, and brand value. An acquisition of Drivetrain Systems International allowed Geely to become a major supplier of automatic gearboxes in China; whereas previously Chinese-made gearboxes had been considered unsafe, Geely was now at the forefront of an upgrade. Through partnerships with global parts manufacturers, such as Johnson Controls, Geely was further able to form a sustainable global supply chain network.

- Mindset Shift. The third transformation pillar was a new approach to business management, with an emphasis on benchmarking and problem-solving to foster constant self-improvement across nearly every function, from R&D to back-end logistics. Over many years, Geely has benchmarked its performance against that of the top companies to identify gaps, root causes, and solutions.

For example, Geely's 2021 “GGQ353” project was a cornerstone for the company as it embarked on the third phase of its improvement and transformation. The target of the project was to measure quality by component type. Geely set the baseline for each business module, along with the respective approaches to performance improvement.

Geely has continued to update its benchmarks so that it evaluates its systems against the highest global industry standards for each business area.

The ultimate goal is to transform from simply meeting industry standards to being a company that sets standards of excellence.

- Innovative Corporate Culture. The fourth and most fundamental pillar in Geely's transformation was fostering an open and innovative culture that has helped Geely’s management improve operational efficiency and contributed to the company’s organic, long-term growth.

The organization itself aims to foster a culture of open-mindedness. Geely has a less hierarchical structure than most Chinese companies. In its offices and production facilities, it remains a family-owned business with a family-like atmosphere, encouraging all staff members— frontline staff, engineers, and top managers alike—to contribute ideas that might lead to product innovation

or improvements in operations, products, and production processes.

Recognizing that human talents are the most valuable asset in an innovative company, Geely management began developing a corporate culture based around the idea that “everyone is an innovator”. In 2008, Geely donated 12.5 million RMB to establish its Future Talent Fund and Li Shufu Education Fund, both of which pro- vide training programs to all levels of staff, with an eye toward meeting the company's needs, keeping up with market dynamics, and staying abreast of technological advancements. Beijing Geely University, founded in 2000, offers comprehensive courses in car manufacturing, engineering, design, and even training models to demonstrate the features of new launches at car shows. A research and development center in the UK focuses on developing lightweight and electric vehicle technologies.

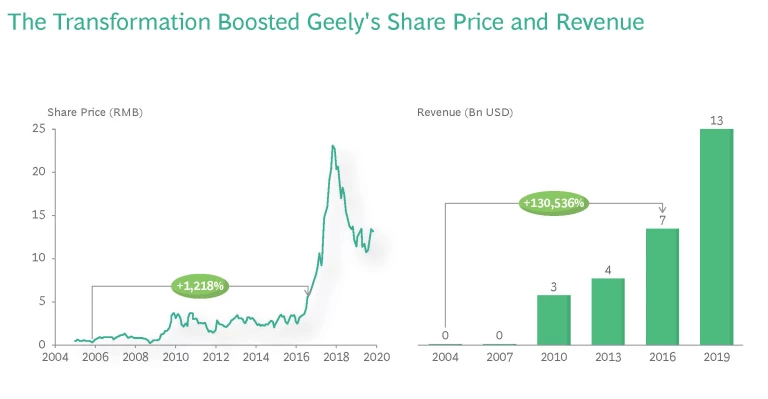

The transformation boosted Geely’s sales by 17% a year on average between 2007 and 2016, significantly outpacing global automotive industry sales, which grew at a CAGR of 3.5% during that same period. As of the end of 2018, Geely’s domestic market share rose to 6.3% and its global market share to 1.1%, with revenues of $15 billion.

Founder and Chairman Li Shufu once said in a public speech, “Technological innovation is key to corporate development; the two are inseparable.” From its determination to turn its brand image around, to going global and continuously nurturing talents, Geely has demonstrated its spirit of proactive entrepreneurship by never settling in its comfort zone. Geely is now well-positioned for continued growth as it embarks on an ambitious plan to establish itself as a leader in such advanced transportation technologies as connected cars, long-distance electric vehicles, and hypersonic trains.

Acer Becoming a Technology Leader

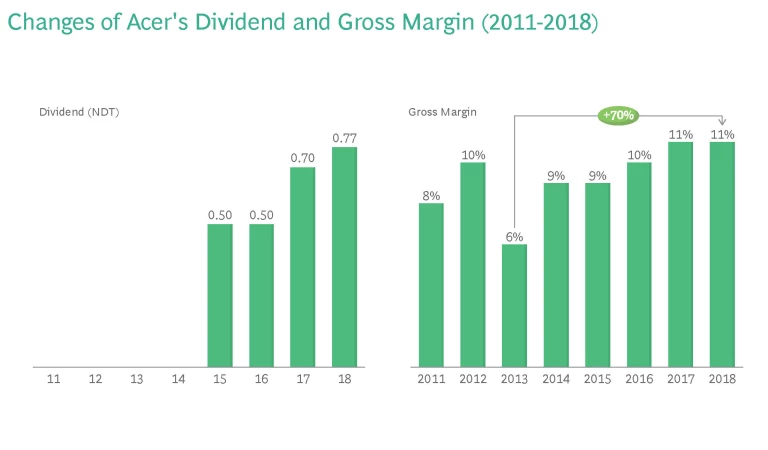

Acer was one of the world’s best-selling personal computer makers throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s. In 2011, however, Acer posted losses of $200 million. Personal computers were losing ground to smart phones and tablets. Acer took a particularly big hit as a company that sold its products based largely on low prices; as a result, it had never developed the brand equity that its closest competitors had.

Losses mounted over three consecutive years, reaching $600 million in 2013, which was two-thirds of the company’s market cap.

In late 2013, founder and then-Chairman Stan Shih, recognizing that the company needed to make some dramatic changes to adapt to the technology disruptions in the industry, invited Jason Chen to join as the new CEO. Chen, who had previously overseen sales and marketing at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and held various sales and marketing roles at Intel, took the helm in 2014 with the goal of repositioning Acer as a technology leader. The transformation took place through a three-part frame- work:

1. Fund the Journey. Acer’s immediate goal was to shift its focus onto high-margin products and services. As Chen saw it, giving up revenue from high-volume sales was an acceptable tradeoff if it meant greater profits.

The company identified two stable markets to target: business laptops, and high-performance laptops and desktops for gaming. Chen saw that there was plenty of room for product innovation in these areas, as well as other areas in the future. The key to building a successful culture of innovation, however, was to operate on the “guard band” theory that sets a stop/loss timeframe for all new business, so that an idea has time to succeed or fail but the risk of failure is contained. With that principle in mind, Acer cut its money-losing mobile business, in spite of the trend toward mobile devices, and concentrated on rebuilding the core PC business.

“The guard band theory came from my semiconductor background,” says Chen. “When investing in new business, we need to set a ‘guard band’ to stop loss as well as set milestones to track our process.”

2. Win in the Medium-Term. To establish a right to win in these new areas, Acer had to overcome the challenge of being a late entrant to the gaming and business PC markets. The company set out to find differentiating factors that could provide a competitive edge, harnessing customer insights and feedback from focus groups to identify Acer’s most unique capabilities.

One of these capabilities was its 300-plus patents on cooling fans, which can boost PC performance and therefore are an attraction to customers in the gaming market who need top-performance products. The customer engagement also helped Acer identify niche markets they could serve. For example, in 2019 the company created the ConceptD line of high-performance PCs for the 15% of gaming laptop customers who are not gamers but designers.

By 2018, Acer had become a global market leader in gaming laptops. The strategy for winning, however, was to keep looking for what might be next. “When the market is changing rapidly, we need to keep looking for opportunities,” observed Chen.

Now that the global PC market has stagnated, Acer is actively looking to diversify its product portfolio by investing in new businesses such as wearable devices, smart city solutions, and the Internet of Things. It is gradually changing its reliance on PCs; in 2013, the core PC business accounted for 83% of Acer’s revenue, but by 2019 it accounted for only 70% of total revenues.

3. Organize for Sustainable Performance. Chen also recognized that he would have to reorganize the company itself. The goal of the reorganization was to build a foundation that would carry Acer through the transformation journey and set it up for sustainable performance over the long-term.

With a range of new products beginning to show a profit, the company has developed an operating model that calls for new businesses to function as separate units from the core. Successful new product divisions are spun off as subsidiaries, with the expectation that a separate management team will be fully responsible for each subsidiary. Since 2014, Acer has spun off three subsidiaries that are now listed separately on the Taipei stock exchange.

It was important, too, to reorganize in ways that would generate a more forward-thinking corporate culture. Chen believes that the company needs a vision that revolves around opportunities for creating value instead of being occupied with solving problems. He wanted everyone in the company to be enthusiastic about value creation. Three organizational levers help fuel this goal for long-term performance:

- Change the Mindset. At the time Chen came in, employee morale had declined alongside the company’s financial downturn. To build a more optimistic outlook, he started a “good news hotline” for employees to report all positive developments in their departments, with a weekly “good news newsletter” to spread the word.

- Optimize the Organizational Structure and Management Mechanisms. Acer set up a new three-level management structure aimed at continuous transformation. A ten-member steering committee of top managers designs the foundations for future plans and strategies. Then, a 40-member executive senior management committee fine-tunes the ideas, challenging assumptions and identifying blind spots. From there, a larger committee of about 100 managers implements the new plans.

- Incubate Innovative Talents and Ideas. Early on in the transformation process, Acer began seeking feedback from the youth market, the main customers for many of its innovations, partly by incubating young talent. To keep pace with this market, every year Chen brings in a new young personal assistant, who then has the chance to move on to another position within the company. A 20-people agile team called the “A Corner” focuses on innovation based on what appeals to the youth culture, while a separate internship program is designed to capture the voices and ideas of Generation Z.

The new capabilities that Acer has developed have made the company a global market leader in gaming laptops. For the last two years the stock has, on average, traded at nearly double its $10 low point, and profits have been in positive territory since 2017.

The company’s sustainable transformation strategy is designed to ensure the company keeps ahead of technology trends going forward. Chen continues to seek niche opportunities, with an eye toward challenging the leading position in high-end computers and developing a product ecosystem that will establish Acer as an innovative lifestyle brand.

Semir Keeping Ahead of Fast Fashion Trends

Zhejiang Semir Garment Co., one of China’s top apparel retail companies, developed a transformation strategy that has brought it to the forefront of China’s growing consumer market. In an industry that must stay on top of changing fashion trends and consumer habits, Semir has created a corporate culture that encourages everyone in the organization to keep generating new ideas.

Qiu Guanghe, Chairman of the company, founded Semir in 1996 as a family business that sold casual apparel aimed at 16-year-olds to 30-year-olds. Part of the strategic planning was to build additional apparel lines and, in 2002, the company established the Balabala brand, which makes clothing for children. Semir was on a strong growth trajectory, and it was listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange in 2011.

By the next year, however, the company was facing an external challenge that clearly required rethinking its brand strategy: extreme competition from the rapid penetration of multinational fast fashion brands such as Zara, H&M, and Uniqlo into China. With disposable income rising in China, consumers were embracing the influx of prestigious fashion brands that gave them good quality for their money. For Semir, the crowded market presented a

need to differentiate its brand, as well as an opportunity to transform in a way that would help assure strong margins and continuous innovation.

As a result, Semir executed its transformation through four main levers to drive growth and operational excellence:

- A Strategic Focus on Children’s Apparel. With the Balabala brand, Semir already had strong capabilities in the children’s apparel market, which was also growing alongside China’s consumer market. The company made the decision to expand its children’s apparel business, with its retail outlets for children’s wear growing from 3,308 in 2012 to 5,293 in 2018. The expansion proved to be foresightful. Not only were parents looking for good value and safety in children’s clothing, but also, China’s repeal of the one-child policy in 2016 brought new assurance that this market would grow.

According to Euromonitor, the children’s apparel market in China is expected to top 272 billion RMB in 2020 and grow annually by 10% for three years thereafter. Balabala is now the market leader in China, with 5.9% of market share as of 2018, and within the Semir Group it contributes 56% of the total revenue.

- Build a Stronger E-Commerce Presence. Semir was a latecomer to e-commerce, launching its platform in 2012, but it quickly became an industry leader in e-com- merce revenue. While at first the e-platform was used primarily to clear inventory from stores, Semir began developing content for the platform including celebrity endorsements of its brands, encouraging employees to share ideas, and using big-data analysis to keep improving the customer experience both online and offline. In 2014, it launched its first exclusive online products.

The e-commerce platform has brought new efficiencies when it comes to collecting and analyzing customer data and developing targeted promotions and sales. Brick-and-mortar stores are still an important attraction to Semir’s customers, however, so its online-to-offline (O2O) model is designed to make the web presence an enhancement to offline shopping. The offline component focuses on the shopping experience, while the online platform creates the synergy of integrated services—a customer can examine merchandise in the store but order a greater quantity or variety online, or make a purchase online and collect the products at a store, for example—as well as a way of keeping inventory available and clearing older or seasonal products through special sales.

The results have been impressive. E-commerce revenue is now the source of 30% of all group sales income. Semir’s Balabala has been the top-selling children’s apparel brand every year from 2015 to 2019 on China’s November 11 Single's Day, when much of the population, whether single or married, celebrates by shopping online.

While Semir focused on new growth engines and go- to-market strategy to drive business results, they also evaluated and improved their internal, operational capabilities to further excel in the crowded market.

- Optimize the Supply Chain. Semir’s management also recognized that in order to keep building on the company’s existing capabilities, they needed to improve their supply chain systems to speed up production and work closely with the best quality suppliers. They consolidated their key suppliers down to a few hundred, the majority of which are renowned clothing manufacturers that supply to large retail companies.

Semir began to place orders eight times a year instead of four as they had previously done. That made it possible to provide customers with greater variety and turnaround. At the same time, the company was able to build closer partnerships with its new core of suppliers and take advantage of the economies of scale—and therefore the optimized profit margins—they could get through bulk purchasing and greater frequency.

- Develop a Corporate Culture and Infrastructure That Foster Continuous Innovation. During Semir’s transformation process it became clear that the fashion market required constant innovation, not just in products but also in the delivery and the business model.

Semir has always been a company that invests heavily in R&D to keep improving its product designs and its technological and innovation capabilities, but in its transformation it instituted a corporate culture with a highly efficient decision-making process and a formal program to encourage new ideas to sustain growth.

In 2015, the Chinese government itself introduced a campaign for "mass, public entrepreneurship and innovation" as an engine for growth, and Semir used a similar model to initiate its "Startup Partnership System." The program includes an in-house competition for new business plans, in which employees can pitch their ideas to colleagues who meet a set of qualifications to become crowdfunders of the startups. The company provides incubation facilities, while employees who invest are able to reap the benefits of successful new lines of business.

Semir has established six such partnership projects with more than 100 employees as shareholders. One of the best-known businesses to come out of the partnership initiative has been MarColor, which makes baby products and clothing. As of 2017, MarColor had attracted 15.5 million RMB in crowdfunding capital and operated 306 stores.

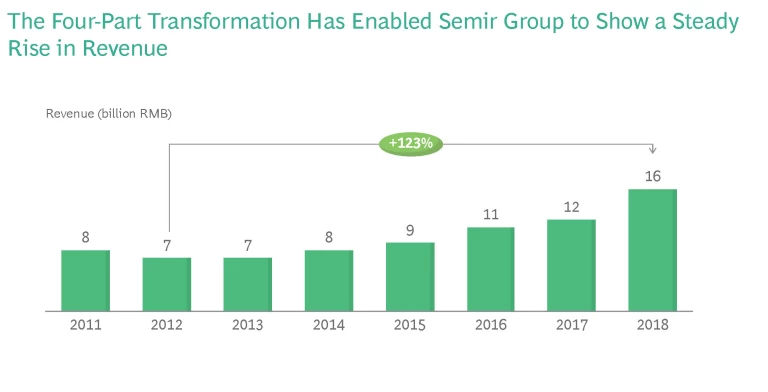

The four-part transformation has enabled Semir Group to show a steady rise in revenue, growing from 7 billion RMB in 2013 to 16 billion RMB in 2018. With a focus on building brands that are part of China’s evolving consumer lifestyles, Semir continues to develop efficiencies and innovations that help it along this ambitious path.

Imperatives Driving Transformation in the ‘20s

While every business transformation is unique, we see five powerful imperatives driving transformation across companies in the 2020s.

1. Digital Disruption. Digital disruption will be a key driver for transformation across industries and geographies. Technology and data are creating unparalleled opportunities to deliver value to clients, but companies have to be visionary about the transformational possibilities if they are to keep ahead of competitors that might, any day, come up with an innovation that disrupts the way an entire industry does business. Capabilities such as artificial intelligence and machine learning—along with low-cost data sensors, computing power, storage, mobile connectivity, and robotics—point to radical changes in customer relationships and business processes in the next few years. In the 2020s, forward thinking companies across almost every conceivable industry will become bionic companies, enhancing their human capabilities with those of digitized machines. Building and managing bionic companies will require a new way of working.

2. Volatile Market Landscape. Most leaders in Greater China today face a future in which parts of their business will lag behind as the markets change, while other parts hold massive potential. Retailers, banks, automotive companies, steel producers, and telecom companies are just some of the many examples. The competitive environment today is far more unpredictable than it was a decade ago. Manufacturing economics and cost structures are changing, and geopolitical crises can erupt with little warning. With expectations of a global slowdown ahead, even the fastest-growing companies have to prepare for a decline in revenue growth. Companies in nearly every sector will need to undergo transformation strategies that require them to trim expenses and manage for excellence and maximum cash flow, while at the same time aggressively pursuing new growth avenues.

3. Opportunistic M&A. “The time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets,” said Baron Rothschild after the Battle of Waterloo. M&A has become a larger part of many companies’ strategy. Overall activity fell in the last two downturns, however, which indicates that if there is another downturn, there will likely be cheaper buying opportunities for the select companies that have the will to pursue M&A deals and have maintained strong enough cash positions to afford them.

The caveat is that the set of available targets they face will include more poor-performing companies in need of a turnaround, rather than thriving companies that can give the buyer an immediate boost. Our research of nearly 3,000 turnaround M&A deals reveals several important empirical lessons for choosing these deals and making them work. The most successful turnaround deals involved companies in the same sector and with similar cultures, ambitious synergy targets, and a turnaround program that was initiated rapidly after the deal closed.

4. A New CEO. Leadership transitions increasingly happen when companies are near a crisis point, and as a result, new CEOs frequently face immediate pressure to make changes. Stakeholders expect a change regime when a new CEO steps in, whether he or she has been promoted internally or hired from outside. The message for incoming leaders is clear: you need to take action immediately.

New CEOs often have a window of time—typically between 60 days and 100 days—after unwinding themselves from most of the responsibilities of their former job and before assuming those of the new position. This period offers a critical opportunity for leaders to define the organization’s collective transformation ambition.

Those CEOs who stand out from the pack quickly define a bold transformation ambition—ideally before they take the reins—and then move forward to energize the organization, prepare the program, and drive the transformation. Through quick and decisive actions early on, when they have time, the board, and investors are on their side, new CEOs can seize the opportunity to lead a transformation and put their company on the right track to success.

5. Preemptive attitude, which is the most effective mindset to transform. “Preemptive transformation”— the art and science of remaking the organization in anticipation of market forces, rather than in reaction to them—is the most effective way to transform.

Outperformers tend to anticipate the impact of a slowdown or disruption and make the first moves. BCG’s analysis of hundreds of transformations found that preemptive change generates significantly higher long-term value than reactive change. Because preemptive transformations take less time, cost less, and increase leadership stability more, companies that undertake them outperform their peers both in the aggregate and across most industries. The effects of preemptive actions are continuous, and the earlier a transformation is initiated, the better the outcomes are likely to be.

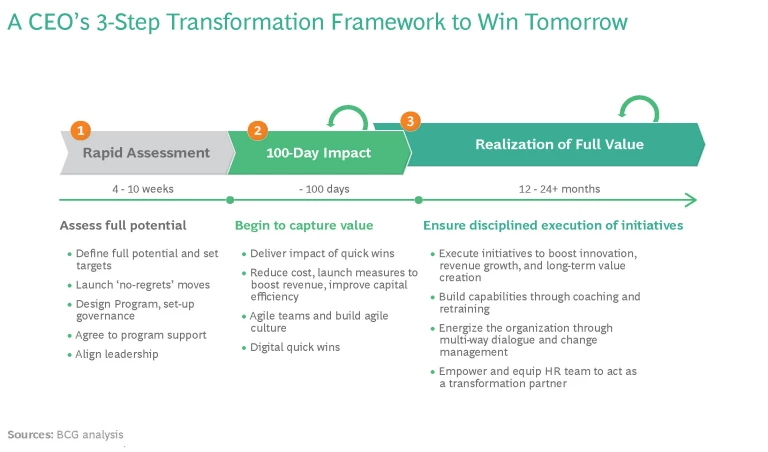

BCG’s Transformation Framework

BCG has helped leaders of companies and other organizations execute hundreds of transformations that have led to significant operational and financial improvement. Based on our experience across industries and regions worldwide, we have developed a proven framework as outlined in Exhibit above.

We have organized the overall transformation process into three distinct phases: Rapid Assessment, 100-Day Impact, and Realization of Full Value.

The initial stage, Rapid Assessment, is aimed at generating a clear picture of the company’s financial situation and identifying the most immediate priorities. Senior leaders take stock of what can be accomplished, and how to fund the journey. At this stage, they should set targets and acquire the tools needed for a successful new operating model. Short-term no-regret initiatives, designed to provide flexibility in uncertain scenarios, are appropriate at this stage and set the tone for what is to follow. At the same time, this is when leaders must let all stakeholders know about the purpose of the transformation and put a long-term formal program in place.

Somewhere between two months and three months into the transformation, prepare to assess the 100-Day Impact. At this point, there should be some improvement in earnings and a positive market response—key indicators that the company has begun to capture value. This is the time to plan longer-term moves for growth, build an agile culture, implement digital initiatives that will allow for quick wins, and strengthen your performance management. In addition, this is when you get down to business with cost reductions and organizational efficiency.

After one year to two years, and into the future, you should be able to gauge your success in the Realization of Full Value phase. This is when you ensure continued, disciplined execution of initiatives throughout the organization, building a culture of sustainable high performance and cost excellence. By then, there should be an operating model in place that has changed the cost base and can make speedy changes as new initiatives and new technologies create more efficiencies. With this model, you can continue to reallocate capital to the company’s growth engines.

The authors would like to thank the following BCG experts of their contribution to this report: Alex Xie, Fang Ruan, Joseph Sun, JT Hsu, Michelle Hu, and Selina Mo. The authors are also grateful to Jan Alexander, Hwa Shiuan, Khushal Puri, Li Gu, Liang Yu, Hui Zhan, Zhuo Chai, and Yoyo Chan for their contributions to the writing, editing, design, production, and marketing of this report.