This article is the first in a series providing insight on why government leaders need to look beyond economic development and prioritize the overall well-being of citizens. The second article will explore how leaders can approach and tackle inequality , and the third will cover direct actions governments must take for the short- and long-term development of countries and their citizens.

One of the biggest lessons COVID-19 taught governments is that societal well-being makes countries more resilient. Nations that invest across a range of development dimensions—such as education, health, infrastructure, and governance—have been better able to cushion the socioeconomic fallout from the pandemic. Our analysis shows that countries with improved abilities to convert wealth into well-being as well as those with high overall well-being tended to mitigate drops in economic performance and limit the growth of unemployment rates during the first year of the pandemic. In contrast, countries with lower levels have fallen further behind, particularly in GDP growth and employment. This aligns with our previous research that shows countries better at converting wealth into well-being were able to recover more quickly from the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

Since 2012, BCG has ranked countries according to a proprietary economic development tool called the Sustainable Economic Development Assessment , or SEDA. (See “A Comprehensive Measure of Well-Being.”) A consistent finding from our research is that the more traditional metrics of economic development, which focus on GDP and other macroeconomic indicators, are not sufficient to gauge the true state of development in any society. Rather, countries need to take a more comprehensive and sustainable approach that incorporates and optimizes societal well-being. Viewed through this lens, SEDA analyses have shown that some lower-income countries are actually better off than high-income countries because they look beyond economic metrics and invest in well-being more broadly. COVID-19 brought in a new dimension—an opportunity to observe how such efforts make countries more resilient in a crisis.

A Comprehensive Measurement of Well-Being

- Economic metrics, including income levels, economic stability, and employment

- Investments in education, health, and infrastructure

- Sustainability in terms of governance equality, civil society, and environment

Even as countries continue fighting the pandemic, they need to think long-term and make investments today that will lead to faster and more sustainable progress during the coming recovery. Specifically, we believe that three overarching themes have the potential to generate positive change across multiple well-being dimensions: accelerating actions to slow climate change, investing in digitization, and strengthening social protection systems to ensure inclusive and equitable growth. Each of these themes should be a priority for governments.

The Pandemic’s Lasting Impact on Development

COVID-19 has left an unprecedented mark on global development. The United Nations Development Programme’s simulations of the pandemic’s real-time impact suggest that the Human Development Index fell in 2020, for the first time since measurements began in 1990. Similarly, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals are expected to be significantly disrupted and many of the historic gains over the past several decades could be reversed, at least temporarily.

At a country level, the pandemic revealed the way that all realms of society are interconnected. Evolving from a health crisis to an economic and education crisis, COVID-19 has led to rising social tensions, high unemployment, and failing health systems, even in high-income countries. In low-income and developing countries, inequality has increased across several realms.

- Income. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that income inequality for emerging-market and developing economies will rise to levels not seen since the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, essentially wiping out a decade of development in these regions.

- Health. Disparities in access to health services—due to factors such as income, race, gender, and resident status—have widened the gap in life expectancy, accentuating the vulnerability of disadvantaged groups within poorer countries.

- Education. According to UN data, close to 1.5 billion students have been affected by COVID-19-related school closures. Inadequate internet penetration has hampered lower-income countries’ ability to pivot to distance learning and likely exacerbated education inequality both within and between countries.

The pandemic has reinforced the need for governments to look beyond income growth and GDP and focus on the broader goal of overall well-being.

Well-Being Stabilized Countries During the Crisis

It’s too early to measure the full response of any country to COVID-19, but early indications suggest that countries with high SEDA scores—indicating higher levels of societal well-being—will suffer less of an impact. Indeed, well-being served as a form of stabilizer, enabling countries to absorb the shock and potentially positioning them to bounce back more quickly once the crisis ends. In our analysis, we looked at two leading economic indicators: economic growth and employment.

Well-being served as a form of stabilizer, enabling countries to absorb the shock of the pandemic and potentially positioning them to bounce back more quickly once the crisis ends.

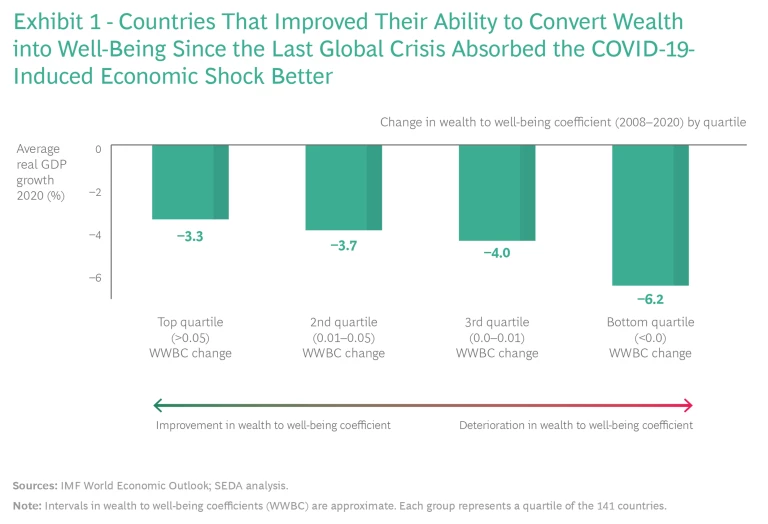

In terms of economic growth, countries which improved their ability to convert wealth into well-being since the global financial crisis, saw a smaller drop in their real GDP growth rate in 2020, while countries that have experienced a deterioration in their ability to convert wealth into well-being saw a correspondingly larger drop. (See Exhibit 1.) This reveals that investing in well-being enhances long term resilience and can further enhance a nation’s ability to withstand future crises. Notably, the countries that experienced the biggest drop in GDP also underperformed significantly in SEDA measurements of governance and civil society, suggesting that these are key dimensions in fighting the pandemic’s economic repercussions. Governance is critical because it boosts transparency and accountability, leading to greater public trust in government and increasing participation and engagement of citizens. Civil society matters because it helps countries deal with the unequal fallout from a crisis—for example, providing support and aid to those who are disproportionately affected.

The positive correlation between wealth, as reflected in per capita income levels, and SEDA scores should come as no surprise. After all, income affects well-being in many ways. At the same time, well-being is not simply a function of income. Many countries at similar income levels have significant disparities in well-being .

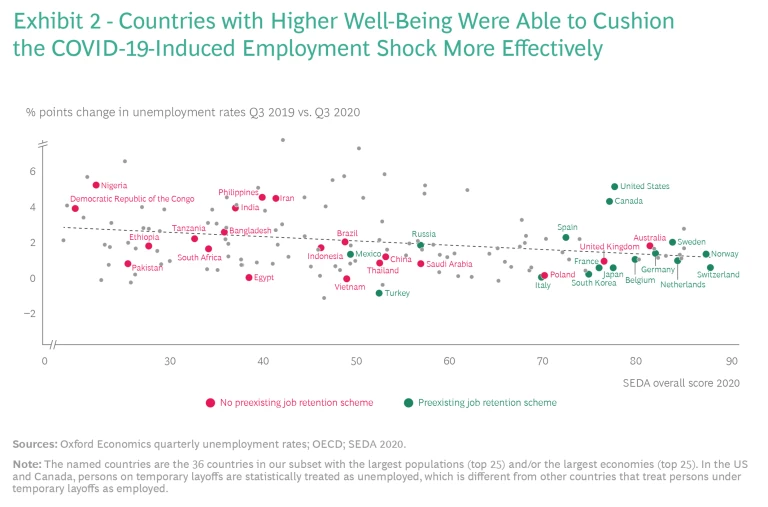

In terms of employment, we saw a similar effect. Countries that had high SEDA scores were better able to cushion the blow of COVID-19 and limit the growth of unemployment. (See Exhibit 2.) Many of these countries already had measures in place to increase the resilience of labor markets—such as unemployment safety nets and job retention schemes. Even in cases where the labor market policies needed to be adjusted, doing so was a faster process than creating them from scratch. A stubborn question remains as to whether retention schemes will lead to a stronger labor recovery once the pandemic ends; to some extent, that depends on whether they support jobs that have been temporarily at risk but are still viable in the long term.

Capitalizing on the Post-Pandemic Recovery

Even as countries continue to face immediate priorities in addressing the crisis, they must reset their ambitions for the future. In fact, severe shocks like COVID-19 present a real opportunity to spring forward and introduce broad reforms toward the goal of overall societal well-being. Regardless of their past performance, governments should seek to leverage the current hardships to reimagine and realign policy imperatives across the full range of SEDA dimensions. From our analysis, we believe that three themes can have a multiplier effect in increasing well-being and thus should be at the top of government agendas.

Accelerate Actions to Slow Climate Change.

The pandemic is estimated to have driven a 5% to 10% drop in CO2 emissions in 2020. That may seem promising as a temporary relief, but compared with the change in trajectory required to slow global warming, it is a mere blip. As the economic cycle resumes momentum, governments and societies have a unique opportunity to accelerate climate-related actions and build a green recovery . Previous recessions have led to an increased adoption of renewable energy sources and battery technologies. In fact, citizens expect governments to tackle climate change as part of COVID-19 recovery efforts. In a BCG survey of more than 3,200 corporate leaders, 77% of respondents say that companies receiving public aid or grants due to the pandemic should take on additional environmental responsibilities and commitments. A recent analysis by the International Energy Agency and the IMF found that a well-structured green recovery plan could lead to an increase in global GDP of 3.5% over the next three years and create 9 million jobs over the same period.

As the economic cycle resumes momentum, governments and societies have a unique opportunity to accelerate climate-related actions and build a green recovery.

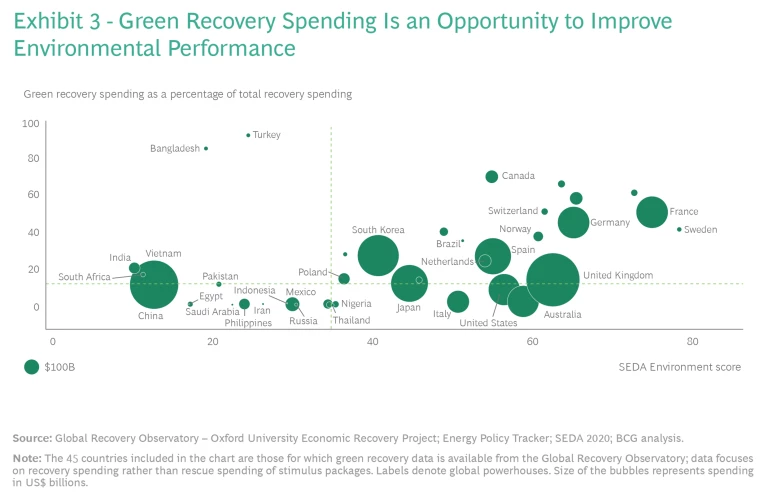

Indeed, some nations are intensifying their investments in environmental well-being. While countries that are already leading in SEDA environmental performance tend to be doubling down on a green recovery, other countries that are not environmental frontrunners have also passed recovery packages with a substantial share of investments targeted at environmental objectives. (See Exhibit 3.) This suggests that these countries see the crisis as an opportunity to accelerate their sustainability efforts.

For example, India’s green stimulus measures include investment in biogas and cleaner fuels, incentives for high-efficiency solar, and advanced battery production. South Korea’s “New Deal,” in addition to focusing on digitization, prioritizes initiatives that support a green transition, including investments in renewables and R&D funding for electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries. China’s green efforts entail substantial funding for EVs and related infrastructure, railway infrastructure development, and electricity transmission. In addition, China—the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases—recently pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 and the European Union has strengthened its commitments under the Paris Agreement by pledging to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030.

Despite these promising early signs, further action will be required. To stay on track to achieve the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, roughly 1% to 3% of global GDP will need to be allocated to climate-change initiatives . To build a green recovery and accelerate actions to slow climate change, governments should focus on four actions.

- Hardwire sustainability into stimulus spending. Focus investments on both decarbonizing existing sectors (for example, industrials and energy) and spurring growth in new green sectors such as green hydrogen. Include incentives and regulatory standards, such as sustainability targets and carbon disclosure requirements, in stimulus packages.

- Create green jobs and prepare for job transitions. Prioritize investments and programs based not on their absolute job creation potential but on the number of jobs created in the green sector. Manage an equitable transition of the workforce toward a zero-carbon economy. Actively invest in reskilling programs to train workers who are displaced.

- Partner with the private sector. To alleviate fiscal constraints, access private funding through structures such as public-private partnerships. Capitalize on the growth in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing and integrate ESG factors into investment processes.

- Coordinate across borders. Partner with other national and regional governments on climate initiatives to make faster progress. The UN’s COP26 climate conference, which has been rescheduled for November 2021, will be a key milestone in monitoring progress toward the Paris Agreement. With representatives from nearly 200 countries, it also provides an opportunity to step up global momentum in forwarding a green recovery from the pandemic.

Invest in Digitization as an Enabler and Amplifier of Well-Being.

Done right, digitization can help countries manage shocks in the short term and keep economies running. In the medium to long run, it can help developing and emerging economies leapfrog developed nations, accelerating human capital development, industry competitiveness, and access to global markets. Indeed, our previous analysis shows that digital infrastructure increases the ability to convert wealth into well-being at lower income levels; that is, its spillover impact on other well-being dimensions such as employment, education, and governance is particularly significant for developing countries.

The spillover impact of strong digital infrastructure on other well-being dimensions such as employment, education, and governance is particularly significant for developing countries.

Several countries have successfully integrated digital technologies into their crisis response; for example, by using mobile apps to trace transmission chains, register populations for vaccines, increase collaboration, and provide community support. Looking ahead, the pandemic has made clear that the future will be even more digital than previously imagined. Many of the behavioral shifts we are experiencing today, such as online grocery shopping and working from home , are expected to endure beyond the crisis.

Specifically, countries should focus on the following priorities.

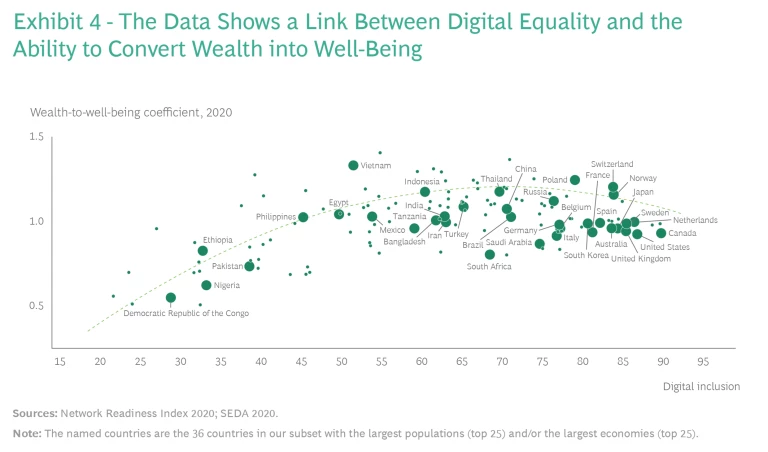

- Bridge the digital divide. As evidenced by those who have been disproportionately affected by school closures and the move to telework and telehealth, digital inequality tends to exacerbate existing social inequality. At the foundational level, countries need to ensure the provision of universal, reliable, and stable connection to the internet. Equally critical to safeguarding connectivity is bridging the access gap. COVID-19 has exposed the hardware divide, in which availability of devices (smartphones, PCs, laptops, tablets) and peripheral services (apps and subscriptions) dictates the extent to which people are able to leverage critical digital services such as e-learning. Furthermore, digital inclusion policies need to be multidimensional—promoting digital literacy, enhancing technological competence, and fostering the effective use of technologies to promote fruitful participation in the digital economy. As Exhibit 4 shows, there is a correlation between a country’s digital inclusion performance (as measured by the Network Readiness Index) and how well it converts wealth into well-being.

- Leverage digital to build more resilient cities. Curbing the spread of COVID-19 has tested the capabilities of urban environments. City resilience will continue to be the main buffer against inevitable shocks, particularly as the 70% the world’s population will live in metropolitan areas by 2050. Big data’s role in smart city platforms will be essential in responding to future disasters in real time.

- Digital government. Governments must continue to expand their digital capabilities with a citizen-centric mindset, as delivering simpler, more seamless, and faster government services becomes increasingly important. By harnessing both the human and technological elements of their organizations, governments can provide positive outcomes for citizens.

- Strike the right balance between data accessibility and privacy. COVID-19 has shown the enormous potential for governments to use and leverage citizen data. Yet this raises important ethical and legal questions. Governments need to safeguard information while instilling high ethical standards for its utilization. For instance, by creating data-sharing frameworks that put in place data use guardrails, governments can support accessibility and adoption without compromising privacy.

Establish Social Protection and Welfare Systems to Ensure Sustainable and Equitable Growth.

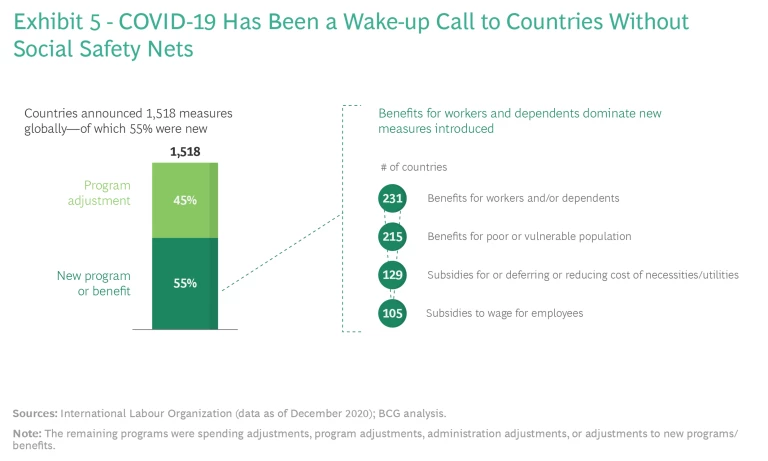

Social protection systems can dramatically mitigate the impact of crises like COVID-19, particularly for vulnerable populations who have been disproportionally impacted . Since the beginning of the pandemic, the number and scope of social protection initiatives has been unprecedented. Overall, as of December 2020, approximately $590 billion (or nearly 1% of worldwide GDP) had been pledged toward more than 1,500 specific measures in 209 countries. More than half of these were for new programs or benefits. (See Exhibit 5.) Many countries prioritized benefits for workers and their dependents along with benefits for poor or vulnerable populations.

Despite these efforts, however, many social protection schemes still fall short. According to research from the UN’s International Labour Organization, 55% of the global population has no form of social protection. About 40% of people have no access to health insurance or national health systems, and only 20% can count on unemployment benefits.

There is a clear need for future-proof welfare systems, which should not only act as a cushion during a crisis but also make countries more resilient and equip them to transition to more sustainable economic growth.

There is a clear need for future-proof welfare systems , which should not only act as an immediate cushion during a crisis but also make countries more resilient and equip them to transition to more sustainable economic growth. It is crucial, therefore, that governments treat the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to rethink their approach to social protection. Rather than a safety net for vulnerable populations, these programs should serve as a trampoline, empowering citizens to be more socially and economically adaptive. The right approach will reduce inequalities, strengthen human capital, and contribute to long-term productivity.

To that end, governments should focus on the following priorities in revamping social protection systems.

- Institutionalize successes. Identify which of the programs launched in response to COVID-19 functioned best and make them permanent. Cut or modify other programs as needed.

- Increase financial sustainability. Look beyond one-time stimulus spending packages to make programs—particularly basic protection measures—that will be viable over the long term.

- Collaborate across stakeholders. Design programs to draw on support from government, business, and citizens.

- Use digital delivery channels that are fast and cost-effective in interacting with participants and delivering benefits.

The pandemic has served as a forced experiment in testing countries’ resilience, and as our analysis shows, the results are clear. Societal well-being not only helps countries during good times; it also makes them more resilient during crises. The SEDA framework is a powerful tool for governments to assess and track their progress in this realm and identify specific policy interventions that will comprehensively improve the well-being of their populations. By focusing on the three overarching themes we identified—slowing climate change, fostering inclusive digitization, and enhancing social protection—countries can capitalize on multiplier effects and accelerate overall progress.