Having shaken off its COVID-19 malaise, shareholder activism has made a speedy recovery. The fourth quarter of 2020 already saw 50% more campaigns than the third. With 49 public campaigns launched during the first quarter of 2021, we are virtually back to pre-pandemic levels.

Activism’s resurgence reflects precrisis trends. Campaigns are more global. Institutional investors are increasingly part of the mix, and they have become more vocal in pushing their agendas. Unlike the “greenmail” campaigns of the past, today’s agendas are often colored by environmental, social, and governance concerns—a very different shade of green. They are also more successful, with activists winning twice the number of board seats in the past decade than in the one prior.

Activist campaigns are all too likely to destroy value, so it’s essential that companies preempt them.

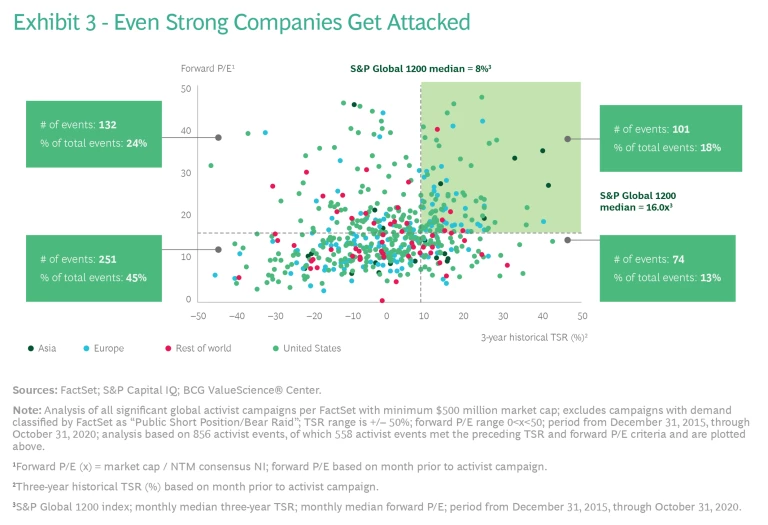

From our review of nearly 900 campaigns over the last 15 years, four critical facts emerge. First, shareholder activism is expanding rapidly, especially outside the US, where companies historically enjoyed more natural defenses. Second, all companies are vulnerable. Although most targets underperformed the market, nearly a fifth had strong shareholder returns and attractive forward multiples. Third, management can lose control of the narrative quickly, with the TSR trajectory typically determined in the first three months after the attack. Lastly, investors are looking closely at how companies performed during the pandemic, not just in terms of financial stewardship, but also at how the company treated its employees and customers during the crisis.

Many activists raise valid concerns, but campaign disruption more often than not destroys value. So it’s essential that companies preempt such actions by adopting a shareholder activist’s mindset and putting their strategic and operating plans to the test. Acting now will determine if the company is leaving value on the table—and boards and investors in the dark—with enough runway to do something about it.

Activism Is Growing Broader, Bolder, and More Successful

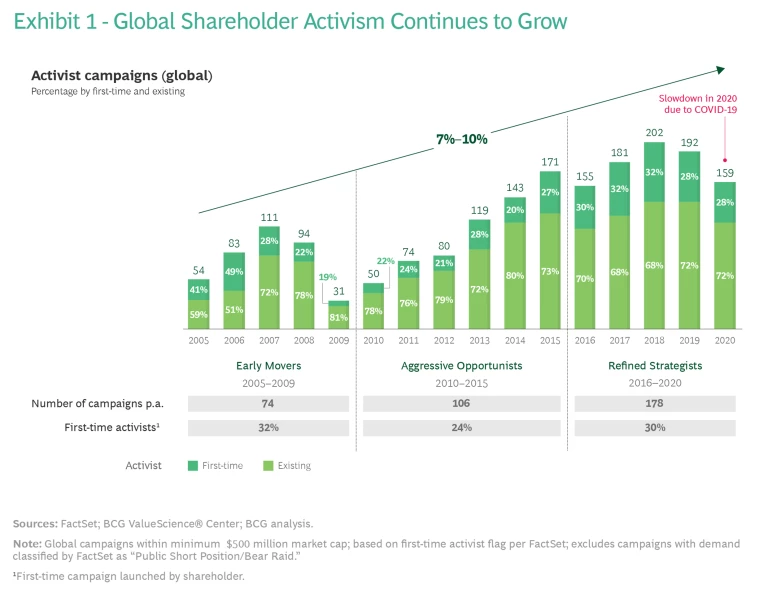

Campaigns are closing faster and handing activists more wins, wrapping up in five months instead of seven and delivering the victors more than 1,000 board seats since 2005. And the number of campaigns is growing steadily. From 2005 through 2009, a period that included the global financial crisis, activists mounted about 74 campaigns each year. A decade later, a period that included a global pandemic, that figure has more than doubled. (See Exhibit 1.) Should growth continue on its current path (a heady 7%–10% CAGR), we can expect to see around 200 campaigns a year, or roughly one attack every other day—a rate that should put companies on notice.

No longer a US phenomenon, activism has gone global, and in a big way. Four out of every ten campaigns over the past five years occurred outside the US, with the biggest surges in Europe and Asia. Activism in these regions increased by a CAGR of 43% and 44%, respectively, between 2016 and 2020. Companies in Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and other parts of the world have also witnessed increased investor saber-rattling, with campaigns growing by a CAGR of 24% over the same period. By contrast, activity in the US rose by only 3%. Many campaigns retain a local character—which means company defenses should also. In Asia, for example, shareholder activists are far more likely to be motivated by balance sheet opportunity than their counterparts in other regions.

Despite regional distinctions, however, we observe several cross-cutting themes. Where short-term financial engineering may have predominated in the past, investor agitators are increasingly pushing for changes that put companies on a stronger long-term footing. More than half of all campaigns globally in the years 2016 through 2020 (55%) were sparked by governance and strategic factors. ESG issues have galvanized particular investor attention, comprising nearly 20% of all activist interventions over the last five years, including climate, diversity, and related demands. The combined assets under management for ESG-driven campaigns now total more than $90 billion, up from $20 billion just five years ago, and these campaigns have become three times more successful over that time.

Activists May Win, but Most Companies Lose

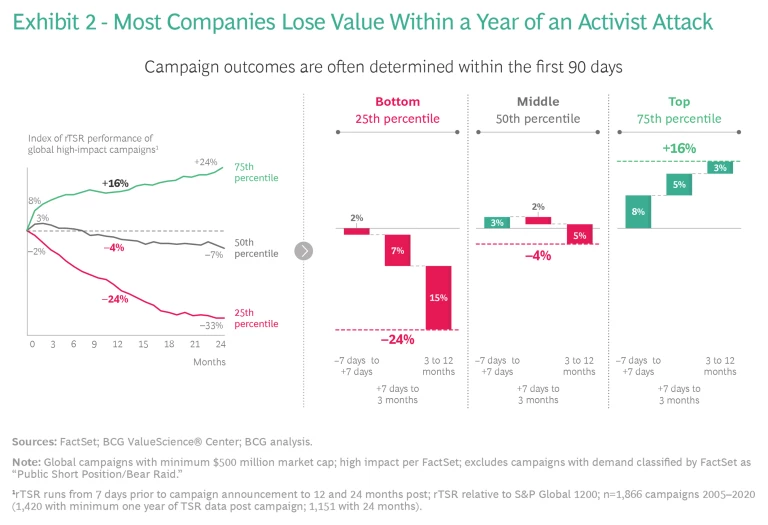

While some shareholder campaigns force bold changes that deliver positive near-term results, these are the minority. Most companies lose between 4% and 25% of TSR within a year of an activist attack. (See Exhibit 2.) Senior leaders are also more likely to lose their jobs; our data indicates that activism nearly doubles the risk of CEO turnover.

Soberingly, the TSR trajectory is typically determined within the first 90 days after a campaign is launched. And for all but the top quartile—the companies with the strongest TSR or price-earnings projections—it’s a downward spiral. Nor are the targets just the obvious laggards. In fact, the bottom quartile makes up only 45% of all attacks, proving that anyone can be attacked. (See Exhibit 3.)

Most companies are vulnerable not because they lack a plan, but because their plans lack rigor. They haven’t done the stress testing needed to surface critical value creation gaps and they’re not acting early enough. Many are also leaving their boards in the dark. Our survey data found that 80% of board directors want to engage directly with shareholders, but only 23% are given the opportunity. And more than two-thirds (69%) want management to provide an independent assessment of the company’s performance, but only 40% of directors say they receive this. By the time leaders reach for the necessary remediations, the 90-day clock has already begun ticking.

Our research and client experience show that deflecting an activist requires more than a “break the glass” plan. It requires looking at the business as an aggressive shareholder might. And that starts by asking some hard questions.

Where Are You Most at Risk?

When attacks happen, most leaders have the same first impulse—they dig in their heels, defend the soundness of their strategy, and seek to hold the activists at bay. But activists don’t just go away. They can dig in their heels, too. Many have invested significant capital and research resources into developing their investment theses and are increasingly creative in the ways they pursue companies.

Keying in on competitive variances and their severity is the best way for management to gauge an organization’s vulnerability.

To shore up their defenses, management should screen for blind spots on at least a quarterly basis. When we wrote “Do-It-Yourself Activism” in 2014, we talked about nine core financial metrics. But today’s diverse activist environment requires broader and more robust screening. Indicators likely to catch an activist’s eye can encompass everything from expense management and governance practices to a list of whatever activist “hammers” are currently in vogue. It’s not uncommon, for instance, for some activists to have a pet practice, such as outsourcing or boardroom diversity, and expressly search for undervalued companies that they feel fall short in these areas. They might also look for potential sale-leaseback transactions for physical real estate or leveraged share repurchases, and mount campaigns against targets that they feel have untapped opportunity in these areas.

Companies then need to run the full set of metrics they develop against a relevant set of peers (every company has some, even those with unique or complex structures) and take a hard look at how their performance stacks up. Keying in on competitive variances and their severity can be uncomfortable, but it’s the best way for management to gauge an organization’s vulnerability.

Are You Managing Your Portfolio for Full Value?

The worst question an activist can ask is the one you haven’t thought about. Management never wants to be in that position. At least once a year—and well ahead of the typical first-quarter spike in activism—leaders should submit their strategic and operational plans to a full examination and ask: Should we pick up the pace of investment in digital or fast-growth areas of the business and starve legacy models more aggressively? What would a private equity owner say about our cost structure if it acquired us? What additional efficiencies would they seek? And are we the best owner of our assets or could we create more value by selling some and refocusing on others?

Much like a war-gaming exercise, the idea is not to validate existing strategy, but to put it through the mill. Leaders should set up a “red team”—a group of individuals who can take an independent view of the company, look out over the next three to five years, and put all potential value creation levers on the table: Maybe aggressive omnichannel integration could lower acquisition costs by 20%? Or perhaps a core technology could generate three times the value if sold or used to kick-start a very different business?

The results of this exercise should give leaders the fact base to underwrite bold change with precision—and a clear rationale to explain why they are not pursuing other changes. Selling a division might raise cash, for example, but it might also raise raw material costs and reduce the company’s purchasing power. A common fact base allows leaders to put emotions aside and create a compelling investor story, helping management make informed decisions and effectively parry potential challengers’ gambits.

Which Moves Should You Make First?

Companies want a balanced portfolio, with wins that deliver over a mix of time horizons. In shaping that portfolio, leaders should weigh several factors. One is speed to impact. Activists typically like cost moves that have fast payback. Outsourcing, for instance, is a notionally straightforward way for businesses to lower costs, but the transition can take several months and a quarter or two beyond that for results to hit the bottom line. Similarly, growth opportunities with proven results, such as optimizing trade spend in retail or accelerating channel sales in software, are welcomed.

Another is balance sheet capacity. Activist investors will seek out lazy balance sheets so that they can demand a leveraged repurchase of shares or other return of capital to shareholders. Companies need to figure out how many degrees of freedom they have in order to get where they want to go and align their financial policy and capital allocation decisions accordingly.

Leaders also need to consider investor expectations. One manufacturer, for example, felt that it had to make big cuts to pay down debt. But shareholder analysis revealed the company’s target investor was more concerned about growth than leverage. Leaders still sought efficiencies, but instead of overhead cuts that would benefit EBITDA, they prioritized efforts that would boost gross margin, such as lowering direct labor through automation and supply chain improvements—actions more likely to appeal to their core investor base.

Do Investors and Boards Feel Included in Your Journey?

Candor is important, even when it prompts challenging discussions. Investors understand that conditions on the ground have shifted and guidance may have to change. But they want to be kept in the loop. Leaders must lay out their value creation plan in clear terms, be up front about existing headwinds, and show how they intend to capture long-term advantage. We routinely ask CEOs how many of their top 15 investors they’ve met with in the last six months. The answer is often surprisingly low.

Candor is important. Investors understand that conditions have shifted, but they want to be kept in the loop.

The same is true for board communications. It takes courage on the part of management to speak candidly about where they’re struggling. But boards don’t want to fly blind, and they’ll welcome the chance to serve as a strategic thought partner. Directors want to hear where things are going smoothly and where the company could be doing better. They want to know what shareholders think of the company’s performance and strategic direction. And they’re keen to hear management’s plans and timeline for addressing performance gaps. Opening up dialogue builds trust between management and stakeholders and also builds alignment on the value creation agenda, powerful means for heading off investor unrest.

Savvy activists are skilled at finding openings through which to drive their campaigns. The best leaders won’t give them any. Those willing to hold their strategy up to the light, probe additional value creation pathways, and proactively engage with their investors and boards will deny activists a platform. Moreover, they’ll create a business that is intrinsically more resilient and ultimately more rewarding to shareholders.