The right design can generate substantial rewards, but intervention also poses big risks for policymakers.

The pandemic delivered a body blow to global trade. But COVID-19 is only the latest setback to the 50-year trend toward globalization in business and the economy. Even before the pandemic, growing trade restrictions, rising tariffs, and increased government intervention were battering the dominant economic narrative of the previous 25 years. Moreover, lingering political unrest in many places is paving the way for yet more interventionist industrial policies and protectionist trade policies around the globe.

Much of the resistance to further globalization should be expected to dissipate. The benefits of trade remain evident, and the vast networks of highly efficient global supply chains built over the last 50 years are unlikely to be completely undone. Still, such factors as political pressure from a squeezed middle class in developed economies, the convergence of national labor costs and productivity levels, and new automation technologies will make offshoring a less dominant phenomenon in the near and medium terms. Rising geopolitical rivalries will likely alter the flow of trade in several key sectors, offering new opportunities for countries with the right policy frameworks, real competitive advantages, and attractive business incentives to attract investments their way.

With business activity worth hundreds of billions—if not trillions—of dollars in flux, there are big rewards for governments that get the policy design and implementation right. There are also significant risks to be overcome, including the economic tradeoffs of various types of intervention and the risks of wasted resources and misdirected efforts.

Below, we analyze the rising interest in localization and offer some strategic considerations for how government ministries and agencies charged with executing localization initiatives can move ahead with confidence that their actions will lead to sustainable growth and remain in conformity with international trade rules.

The Revival of Active Industrial Development

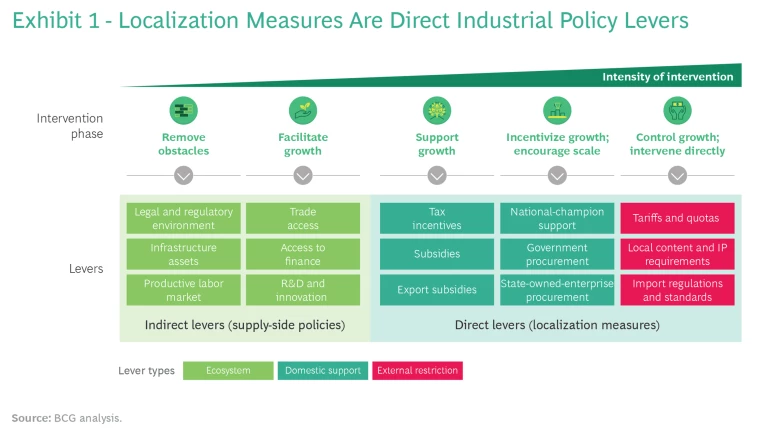

We define localization as a comprehensive set of direct-support industrial policies that include tax and government procurement incentives, targeted incentives such as subsidies, trade interventions, and local-product-content requirements for investment. (See Exhibit 1.) Combined with supply-side policies (such as business-friendly macroeconomic policies and minimal bureaucratic red tape), they form a comprehensive policy mix designed to attract investment and support the growth of local industries.

Typically, five factors drive active industrial policies. The first is a well-established economic rationale for government support of infant industries. Localization measures are not a recent invention; they have been widely used since the early days of industrial development. Nor are they incompatible with globalized rules-based trade. Rather, they serve (ideally) as short-term support enabling less-developed domestic sectors to counterbalance—and eventually overcome—the initial scale and know-how benefits of more established competitors worldwide.

The second factor is the increasing viability of localization resulting from the declining benefits of offshoring as labor costs and productivity converge across countries. Automation is offsetting much of the labor cost disadvantage of high-cost countries. For example, the rising use of automation in production facilities is expected to boost output per worker by up to 30% in the medium term. Manufacturing industries are expected to see a 35% increase in reshoring for each additional 100 robots installed per 10,000 workers.

Third, a globalizing world and splintered value chains inevitably bring an increasing risk of supply chain disruption. Such an interconnected, but more volatile, system requires the buildup of buffers in home markets, at least in strategic industries. The 2020 lockdowns in Hubei province, for example, home to one of the largest automotive production and supplier hubs in the world, contributed significantly to weeklong factory closures in Europe and Asia stemming from the unavailability of critical parts. In response to COVID-19, companies are adding redundancy to their global supply chains, but they are also shifting certain parts of the value chain to new locations in order to reduce geopolitical and natural-disaster risks. In addition, they are moving operations closer to end markets as a hedge against these and other exogenous shocks.

With business activity worth hundreds of billions—if not trillions—of dollars in flux, there are big rewards for governments that get industrial policy design and implementation right.

The fourth factor driving active industrial policies actually arises from the apparent success of these policies and their increasing application around the world. Intensifying public-sector competition can be observed in growing government efforts to nurture industrial “national champions,” either through direct ownership or orchestrated support policies. Among the world’s 2,000 largest companies, the percentage of assets controlled by state-owned enterprises has been on the rise for years in both advanced economies and (especially) in emerging markets . These enterprises’ share of revenues among the 2,000 largest companies soared from about 5% in the 2000–2002 period to about 29% in 2020. While state-owned enterprises tend to perform less well on average than other firms on strictly financial measures, their typically more patient investing approach allows them to focus on the longer term, and many now play on the global stage. Similarly, certain privately held firms in developing markets have been able to leverage a favorable local policy environment and market position into global leadership.

Finally, social discontent, partly stemming from subdued middle-income growth and economic dislocation in developed countries, is fostering nationalistic sentiments. Localization appeals to populist political elements. Offshoring typically hits lower-income groups in advanced economies first, and we have seen populist movements tap into social discontent by advocating for more localization measures.

For all these reasons, we expect pressure for more direct government intervention to continue in the foreseeable future. The question for governments remains: How can they effectively respond by applying the most competitive set of industrial-development policies?

Firms’ Perspective on Localization: No One-Size-Fits-All Policy

Companies have lots of reasons to move, expand—or stay put. Their need for support will vary by their motives for investment, which can include advancing into new markets, purchasing strategic assets, or seeking lower production costs. Successful localization policies are tailored to meet these varied requirements.

Reducing business risks is a common priority for all types of firms. In a recent World Bank report, almost 45% of companies cited its critical importance in their selection of a location. Broader supply-side policies remain the most relevant element in most successful mixes of investment-attracting schemes. Incentives and the general cost of doing business, on the other hand, are critically important to only about 20% of investors targeting efficiency gains through reshoring activities.

Global differences in production costs are indeed converging. That said, given most companies’ high sunk-capex costs and the massive, system-wide costs of rearranging a supporting ecosystem of suppliers and logistics networks, the economic benefits of reshoring are often marginal and temporary. Companies thus often require large incentives to move. Reshoring remains a costly and potentially a risky exercise.

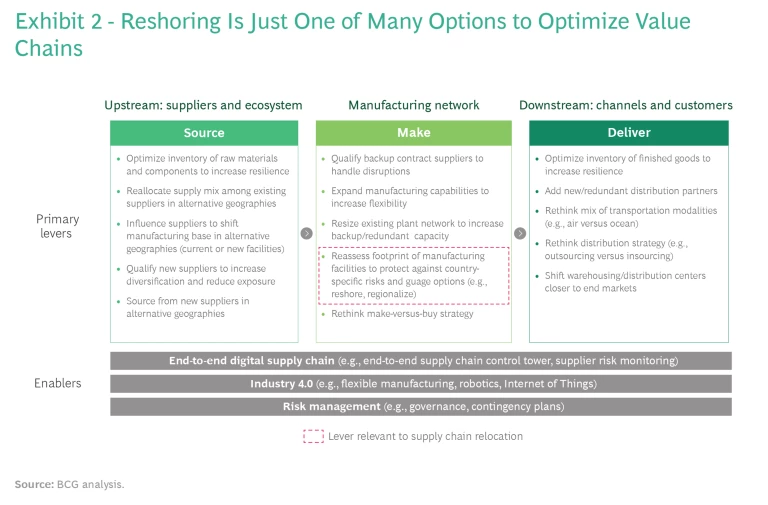

Companies have many alternative, often less expensive, options to reshoring. They can optimize sourcing, production, and delivery processes using a multitude of levers, from inventory optimization, supplier base reshuffling, and increased manufacturing productivity to optimized distribution strategies. (See Exhibit 2.) As governments craft their reshoring incentives, they need to understand companies’ opportunity costs in order to determine how best to attract new investment. For instance, trade policy alone will likely not suffice in convincing companies to relocate (and could have detrimental effects elsewhere in the economy).

Key Principles for Localization Policies

Regardless of the particular localization strategy a country pursues, active industrial policy will always require carefully calibrated government action. Getting localization right is not easy. In our work on more than 700 industrial-development programs worldwide, we have found that a well-orchestrated governmental approach, targeted at specific investor needs and clusters of geographically concentrated, interlinked value chain segments, is most effective. Though each country is different, we have identified eight common principles that can help all public-policy agencies with responsibility for industrial development focus their efforts and avoid the pitfalls of wasted resources.

Cluster-Focused. Formulate a strategy around developing local economic clusters rather than isolated industries, sectors, or companies. Significant know-how and capital synergies can be generated from dense networks of interconnected companies, institutions, and workforces. Indeed, the very strength of a given sector depends on the competitiveness of its supporting ecosystem. A cluster-based approach is also easier to implement in a WTO-consistent manner than one focused on specific firms or sectors.

Enduring. Invest in target clusters that possess sustainable competitive advantages on a global level. Take the example of Singapore, which used its natural trade center location to develop a series of regional logistics hubs. The government took the crucial initial step of investing in large infrastructure projects (such as the Jurong Port and Changi airport). The competitiveness of these assets helped unleash sustainable private-sector and export-led growth.

Incremental. Build up new clusters incrementally by focusing on adjacencies to established clusters and capabilities. Approach big bets on new sectors with care, especially if there are few linkages in know-how or expertise to the current local economy.

Integrated. Integrate clusters into already existing sophisticated regional and global value chains, rather than trying to localize entire value chains. Most industrial value chains are and will remain integrated internationally. Countries still do best when they A well-orchestrated governmental approach, targeted at specific investor needs and clusters of geographically concentrated, interlinked value chain segments, is most effective. focus on where the local economy can bring efficiency and value to this broader chain

A well-orchestrated governmental approach, targeted at specific investor needs and clusters of geographically concentrated, interlinked value chain segments, is most effective.

Customized. Leverage existing local assets and policy capabilities to support the particular needs of each cluster. The choice of direct-support localization measures should be carefully calibrated to leverage your strengths. China, for instance, utilized its immense market size, vast labor supply, and sophisticated centralized economic planning to develop long-term cluster localization efforts that have spanned decades and produced such national champions as Huawei, SAIC Motor, and JA Solar. Countries with smaller markets and less central planning need to adapt their localization approach to the levers best suited to their circumstances.

Policy-Led. Prioritize supply policy levers at each stage of intervention, regardless of cluster maturity. Enabling an ample supply of skills, capital, and infrastructure, as well as an easy-to-navigate regulatory environment, is the most cost-effective (and indeed necessary) way of removing obstacles to growth. Direct-support localization measures, such as subsidies, should be focused on early-stage development to help reach minimum viable competitive scale and capability.

Open to Competition. Ensure that supported clusters are exposed to domestic or international competition—or both. Excessive or overextended protection creates negative incentives, making clusters less efficient and innovative. There are few examples of highly protected domestic producers that are competitive in export markets. The successful Japanese and South Korean buildup of multiple national champions in a given sector, such as consumer electronics, combined with a clear export orientation provides a successful benchmark.

Aligned and Orchestrated. Align industrial policies to national goals and harmonize them across government ministries, academia, and private stakeholders to maximize synergies. Well-designed governance overcomes complexity by reducing conflicting goals and duplication costs.

Bringing It All Together: Four Successful Localization Strategies

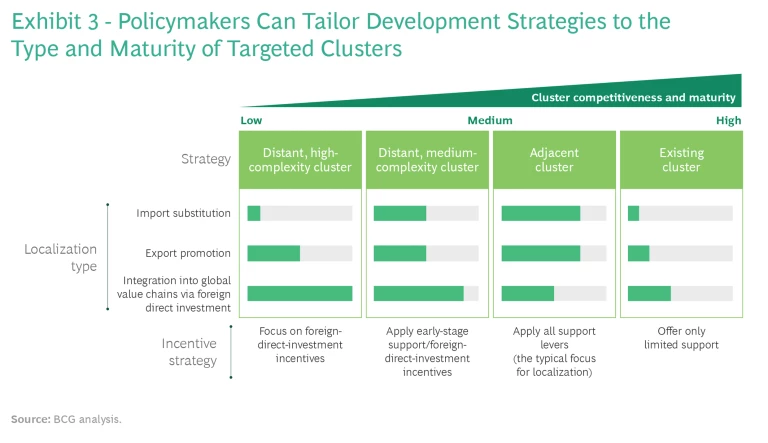

Bearing in mind the general principles outlined above, public policymakers should apply combinations of active industrial policies according to the type and maturity of the targeted clusters. (See Exhibit 3.)

In the early stages of cluster development, when competitiveness tends to be weak and scale in the local economy is lacking, more interventionist measures can be effective (so long as longer-term competitiveness fundamentals are in place). As clusters take hold and grow in strength, direct-support subsidies become less effective, and competitiveness is primarily ensured through a well-orchestrated supply-side policy landscape.

Existing Clusters. These ideally require little or no direct support. They are typically efficient as they are and should be supported mainly with supply-side policies (macroeconomic policies and policies that increase the ease of doing business) and export promotion programs. Support for R&D can help clusters expand on their value-added capabilities.

Adjacent Clusters. These clusters are not yet established in-country but require input factors similar to those of existing clusters. They are typically high-potential targets for direct-support localization measures. Countries can benefit from incrementally expanding the accumulated know-how, skills, and scale of existing firms into new business fields, which improves the new clusters’ likelihood of success. The full host of localization support levers are typically effective when targeted at investor needs and flanked by ecosystem-level enabling policies. Best practices include focusing on achieving export competitiveness early on. Singapore’s gradual, long-term-oriented industrial evolution from metal engineering to high-tech production methods and supporting services (such as finance) provides a good example of climbing up the value chain in adjacent clusters. Likewise, Mexico was able to leverage its automotive supply capabilities based on fabricated metal parts into its growing aerospace cluster.

Distant Medium-Complexity Clusters. These are clusters that are far from current areas of strength in the local economy and are more difficult to enter because of lack of scale and know-how. However, if production and service delivery are not overly complex, know-how can be built up or imported more easily. Assuming the availability of long-term competitiveness fundamentals, governments should apply a mix of direct-support localization measures (such as offtake agreements), with a particular emphasis on strong foreign-direct-investment support for integration into global value chains.

Distant High-Complexity Clusters. Targeting infant technology-intensive and high-value-added clusters is typically best achieved by integrating into global value chains via foreign direct investment. Direct-support localization measures around government procurement usually provide insufficient incentives for firms to relocate, given the wide array of supply-side preconditions and the sophistication required to compete in these clusters.

Active industrial-development policies are on the rise again, and we expect global competition in such policymaking to further intensify. That said, fundamental principles continue to apply. Governments should focus on sustainable, long-term competitive clusters adjacent to those in the current local economy. Public-policy managers should bear in mind the premium that investors put on stable, low-risk, competitive business environments and mix direct support with a strong emphasis on enabling the supply-side environment. Integrating into existing global value chains via foreign direct investment remains the most viable path to export-led growth and the establishment of new technology-intensive clusters in any country.