Debates around social and political issues are increasingly unavoidable, especially as social media platforms allow people to make their views public. This has increased both the pressure on business leaders to weigh in and the opportunity for them to do so.

However, the emotional intensity around politicized issues means speaking out, even in a measured manner, can provoke antagonistic responses. After a tragic school shooting in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, one major airline eliminated a discount for NRA members. Though the change affected only 13 people, it set off a significant backlash; state lawmakers threatened to eliminate $50 million in fuel tax exemptions. Not only did the backlash have negative effects for the company, it also threatened to undermine its well-intended societal impact agenda by inadvertently fueling additional antagonism.

Remaining silent increasingly comes with risks as well, especially as consumers believe businesses should have a voice in political and social issues.

In these heated times, CEOs have thus been left to wrestle with a vexing dilemma—“Should I take a stand on this issue, or should I just stay out of it?”—with seemingly no good answer. How did this arise, and what can CEOs do about it?

The predicament CEOs currently face is largely due to the phenomenon of social polarization, which is already impacting businesses and the societies in which they operate. Developing a nuanced intervention strategy will require a fuller understanding of the ways in which polarization arises and escalates, as well as its impacts and implications.

The Growing Social Divide

Social polarization can be defined in many ways, but a useful definition for understanding the phenomenon and its effects is “a lack of overlap of individuals’ beliefs or traits across different groups.” This can in many cases also lead to a lack of intergroup communication, shared perceptions, and positive sentiment.

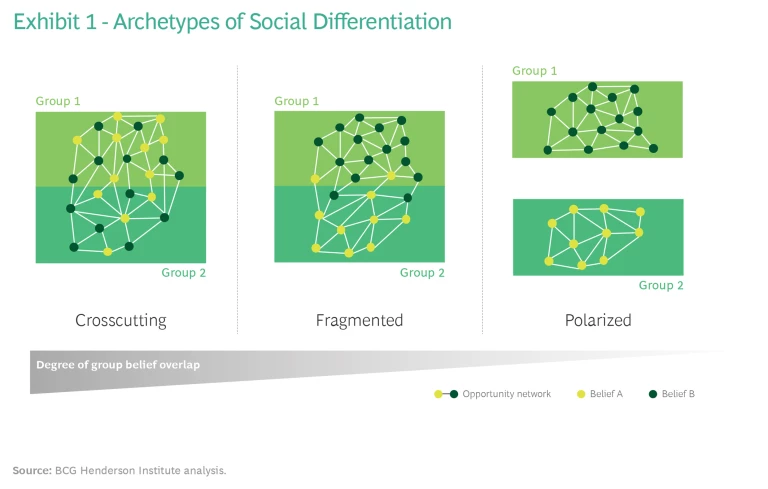

Polarization is at the extreme end of a spectrum of social differentiation. (See Exhibit 1.) Increased differentiation is not uniformly negative—clearly defined identities can create strong bonds within a group (sometimes called “bonding”). However, when it progresses to extreme levels, heterogeneity of beliefs within groups and interactions between groups (“bridging”) are reduced or eliminated, with damaging effects.

- In crosscutting societies, groups contain heterogenous belief systems, and group traits are broadly defined. Individuals are likely to be exposed to diverse perspectives within their groups, which increases the ability to innovate and accept new ideas. Additionally, because traits are shared across groups, individuals may have many beliefs or traits in common with members of other groups, increasing their ability to communicate, cooperate, and relate. Though differences of opinion can cause friction within groups, the traits that individuals share across groups can create common ground and enhance intergroup cooperation.

- In fragmented societies, groups have a narrower set of defining characteristics, and beliefs can be sorted into corresponding groups; however, individuals can hold diverse, group-spanning beliefs. These societies also contain diverse individual identities and perspectives—however, as group identity becomes defined by specific beliefs or traits, competition can arise between groups with different goals, leading to conflict over contentious or consequential issues. Despite this conflict, broad individual belief networks enable coordination between groups based on shared traits or interests, which facilitates collective action while preventing the collapse of society into permanent, antagonistic camps.

- In polarized societies, group beliefs are narrowly defined and rarely overlap. Clear group definitions can provide individuals with a sense of belonging, and basing identity on clearly defined in-group characteristics such as political views can increase engagement in civic life. However, bridging or cross-group interactions are severely limited in polarized societies, and group identity becomes defined by a few narrow traits. Individual activities may be limited by group membership, which can restrain social interactions and economic opportunities. Polarized societies may be characterized by acrimonious “us versus them” public debates, which can be exacerbated by a polarized media and ubiquitous “one-sideism” that leaves little room for common ground. Misinformation spreads easily because members of different groups do not directly interact, leading to increases in misperceptions and intergroup antagonism.

Evidence suggests that societies are shifting toward a more polarized state, particularly in the United States, and this shift manifests in multiple ways.

One manifestation of polarization is an increase in the distance between group positions. Dissention between major groups within the United States has been increasing over the past several years. For example, between 1994 and 2014, Democrats and Republicans’ median views on issues like the environment, corporate regulation, and immigration drifted apart significantly, especially among the most politically active.

A 2019 study found that, on average, Democrats and Republicans believe that 55% of the opposing party hold “extreme” views, but only about 30% actually do.

This may be due partly to an increase in intergroup misperceptions. A 2019 study found that, on average, Democrats and Republicans believe that 55% of the opposing party hold “extreme” views, but only about 30% actually do,

Finally, intergroup antagonism has intensified recently—notably, between 2014 and 2016, the share of Democrats and Republicans who view the other party as dangerous to the nation’s well-being rose by more than 10%.

This is not just a political phenomenon. The job market in most advanced economies has also become increasingly polarized: both high-skill and low-skill jobs have increased, while there has been a hollowing-out of mid-level employment. Between 1980 and 2010, the share of US middle-class jobs dropped by almost 10 percentage points (pp),

The Progression Toward Polarization

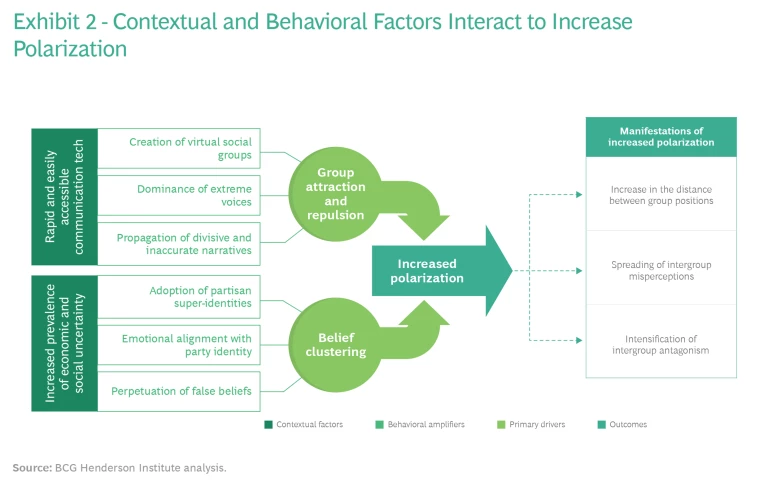

What’s behind the increase in polarization? Systems analysis suggests two ways in which societies move from crosscutting states to more dangerous polarized states—each of which has recently been accelerated by contextual factors.

To ensure their survival, early humans often needed to quickly identify others who could offer support by sharing resources or providing security.

Growing societies tend to naturally absorb newcomers and new perspectives and become diverse. If a diverse society is crosscutting, individuals will tend to interact more freely with members of other groups. However, because attraction and repulsion cause people to move closer to others who are similar to them, a crosscutting society can easily become fragmented if groups become too homogenous. Despite this change, important group-spanning beliefs and connections can be maintained, and new ones can be created.

Recent advances in communication technology have amplified these effects and accelerated the transition from fragmented societies to polarized ones. Technology enables access to new perspectives without geographical proximity, such as shared neighborhoods. This lack of basic commonality may hinder social interactions or empathy and may amplify intergroup bias, especially once people begin to engage only with opinions that reinforce their current beliefs—often without recognizing that the information they consume may be biased or inaccurate.

Technology creates a new attention economy that prioritizes sensationalism over objectivity.

Additionally, technology creates a new attention economy that effectively prioritizes sensationalism over objectivity.

A small number of extreme voices can dominate public discourse and group image by taking advantage of this attention economy, prompting opponents to further differentiate themselves in response.

Though the consequences are significant, these factors alone will not trigger the progression toward a fully polarized state if traits and beliefs are still crosscutting, in which case opportunities for bridging and social contact still exist. Polarization requires the additional narrowing of group norms and the correlation of previously independent beliefs, which contributes to the collapse of group belief network dimensionality by reducing the set of acceptable beliefs within each group.

When beliefs are independent and uncorrelated, groups can include many different traits, which enables the emergence of broad, overlapping belief networks. Individuals can share beliefs or traits across groups—while maintaining one or more group identities—and the potential for cross-group interaction increases. In this state, a society can remain fragmented.

However, when beliefs become highly correlated or “stacked”—such as during times of conflict or resource scarcity—they begin to align more closely with group identities. Group belief networks become more homogenous and cluster tightly around narrow sets of highly correlated beliefs, which hinders overlap across groups. As this occurs, society is more likely to progress toward a polarized state.

Today, we also see the progression toward a more polarized society being fueled by increased economic and social insecurity, including income inequality.

As identities align under group labels, people react more emotionally to views that threaten their group, and they increasingly mistrust those not in their group, hindering impartial discourse. Partisan “super-identities,” for example, are common in two-party political systems and occur when support for political parties (or individual candidates or leaders) subsumes other aspects of social identity. In groups defined by these identities, beliefs that do not align with one’s political affiliation are considered unacceptable, and political opponents become enemies, leaving little room for moderate, shared, or apolitical positions.

As group overlap declines further, individuals may have easy access only to the information and opportunities that other group members can provide, which can disadvantage members with lower economic standing and lead to clustering of economic outcomes. Furthermore, as negative misperceptions spread, the friction between groups can cause some individuals to be actively excluded from certain opportunities—such as employment—on the basis of their group identity.

With few shared spaces or activities (both online and offline), group interactions further devolve. Negative misinformation spreads easily, increasing perceived intergroup differences and antagonism, while also driving growth of real differences and antagonism. As differences between groups—both real and perceived—increase, the forces of attraction and repulsion become even stronger, which in turn prompts further group sorting and clustering. As this progression continues, society becomes increasingly polarized.

This progression can have severe consequences for how a society operates. In crosscutting or fragmented societies, groups can respectfully engage and disagree on a broad range of issues despite their group labels. Once polarized, however, the rise in antagonism and mistrust can lead to a persistent breakdown of civic norms, and groups may become unable to respectfully engage and disagree—even long after the conditions that caused the polarization have been resolved. Debate and disagreement may descend into unproductive group conflict, prompting large majorities in polarized societies to disengage: 86% of Americans say they feel exhausted by division in politics,

Once polarized, groups may become unable to engage and disagree respectfully, even long after the conditions that caused the polarization have been resolved.

The Problem for Businesses

Polarization has the potential to alter individual behaviors outside of politics as well, and major changes to the everyday choices of companies’ customers, employees, or other key stakeholders can have significant consequences.

To a certain degree, polarization can increase in-group affinity and engagement for businesses that are able to harness its effects. Companies and brands that engage in partisan behavior can benefit from a first-mover advantage and differentiate themselves from their competitors to capture additional market share. For example, Patagonia stands out from peers by proactively taking steps to be environmentally conscious and leading the industry in a more sustainable direction.

When social differentiation fully descends into polarization, however, the potential negative impact on companies can be severe. The consequences for businesses often align with the manifestations of a polarized society: increases in the distance between group positions, increases in intergroup misperceptions, and intensification of intergroup antagonism.

- Increases in the distance between group positions can harm businesses through decreased loyalty from consumers with different opinions, restricted market size, restricted access to top talent with different political affiliations, or inefficiencies and frictions from employee protests or walkouts. For example, in 2018, employees of a major tech player pressured the company to drop its bid for a project with the Department of Defense by threatening not to work on it because the views of the DoD were seen as antithetical to many employees’ personal beliefs.

- Increases in intergroup misperceptions can harm businesses through time spent crafting public statements to counter misinformation, decreased access to capital during or after major scandals, friction costs from internal conflict, market unpredictability, or cost of additional security measures to protect employees from physical harm. For instance, after the 2020 US election, a manufacturer of voting systems faced serious threats against its employees, some of whom had to be moved to secure locations.

- Intensification of intergroup antagonism can harm businesses through restricted access to certain customer segments based on group affiliation; limited availability of external partnerships; increased employee attrition; increased cost of additional recruiting activities; inefficiencies from internal conflict, leadership changes, market unpredictability, or risk; opportunity restrictions; or reduced sales from boycotts. For example, a major food chain was targeted by protests and boycotts for nearly a decade because of its donations to organizations that had allegedly taken anti-LGBTQ stances.

17 17 Heil. “ Chick-fil-A drops donations that angered LGBTQ groups, and conservative leaders cry betrayal,” The Washington Post, November 2019.

Because polarization is driven by psychological and structural forces, we cannot simply reverse its progress. However, that does not mean that its consequences cannot be managed proactively. As polarization, accelerated by social media, moves from the ballot box to the family dinner table to the boardroom, doing nothing may no longer be an option. And taking a stance on one side of a debate, however well-intentioned, may be too crude. Instead, CEOs need more effective and nuanced ways to respond.

Taking Action—Not Just Taking a Stand

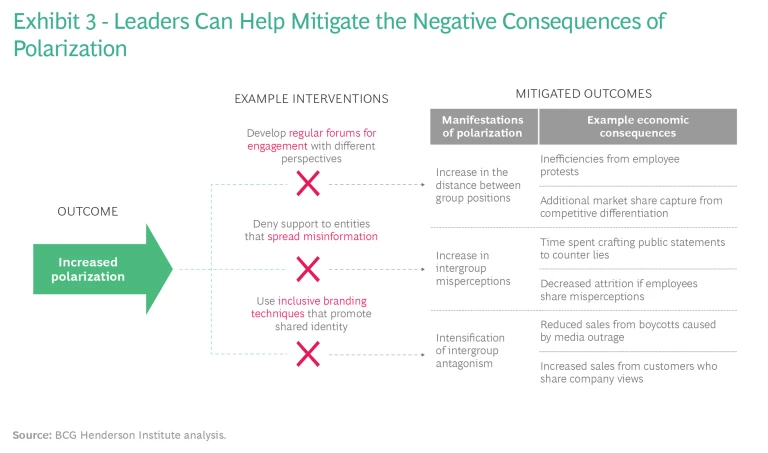

Currently, many CEOs respond to social issues by asking themselves, “Should I take a stand, or should I stay silent?” At a recent leadership conference, CEOs themselves ironically appeared to be polarized on the issue—some said that it is not their job and that their boards would not tolerate taking a stance, while others said that their employees and their own moral convictions left them no choice. Although either option may be useful in certain circumstances, each can backfire as well. Rather than choosing between these binary options, CEOs can instead take a deeper, more systemic view of the problem and identify ways to address polarization structurally and reduce its negative consequences for businesses and societies:

- Reduce the distance between group positions. As groups become more narrowly defined and cross-group interactions decrease, groups are more likely to adopt opposing views than to compromise—because of the lack of overlapping perspectives. CEOs can introduce individuals to novel and diverse perspectives that will help broaden their thinking. For example, this can be done by developing regular forums for cross-group engagement, such as a speaker series for employees or moderated discussions on social media. Additionally, CEOs can develop diverse employee teams and actively encourage cross-group collaboration. The workplace has an important role to play in fostering cross-group collaboration across society.

- Reduce intergroup misperceptions. The lack of cross-group interactions and the development of extreme views promote the spread of misinformation about other groups’ members. CEOs should not fall into the trap of “both-sides-ism”, but they can provide balanced, evidenced information and contribute to building trust in facts. For example, CEOs can deny verbal and financial support to groups or individuals that spread misinformation or conspiracy theories, or they can promote the use of fact-based research and data-based analytics to inform business decisions and public communications.

- Reduce intergroup antagonism. Decreasing interactions and widespread misinformation can contribute to the development of negative sentiment toward members of other groups. CEOs can help to create a shared sense of community and purpose that spans the boundaries of traditional group identities. For example, CEOs can use inclusive branding techniques that promote an apolitical shared identity, or they can identify and eliminate the company’s use of language, euphemisms, or social processes that inadvertently target certain groups and drive further division. In one such instance, Unilever recently announced it would stop using the word “normal” in its product packaging to prevent some consumers from feeling excluded.

18 18 Denham. “ Unilever set to strip ‘normal’ from all beauty products and advertising,” The Washington Post, March 2021. Additionally, CEOs can highlight inclusiveness as a key company value, to emphasize the importance of cooperating with dissimilar others, and develop internal and external forums to address intergroup antagonisms. Once a brand develops a reputation for openness, honesty, and inclusivity, customers will be more likely to trust it, and a trustworthy brand will be better equipped to withstand the potential dangers of increasing polarization.

Polarization is not going to go away anytime soon. By helping to structurally reduce and mitigate the negative consequences of polarization, CEOs reduce the level of harm that polarization can inflict within their broader societies and within their companies. (See Exhibit 3.) As members of different groups engage more sincerely, they may discover that they have more in common, encouraging attraction and reducing repulsion. Increasing cross-group interactions will decrease the spread of divisive narratives and, consequently, intergroup antagonism. A decrease in antagonism will enable individuals to embrace diverse, overlapping group identities without fear of social backlash, preventing further clustering and radicalization of group identities.

Polarization is a complex issue that can create severe ramifications for businesses. However, with a better understanding of the mechanisms behind polarization, CEOs will be better able to both recognize the changes occurring in their societies and understand their options going forward—options that go beyond the simple choice of taking a stand or not.