Some organizations are champions for social change, while others try to maintain a lower profile. All of them need a dedicated corporate-activism capability.

Most CEOs understand that their employees, customers, and other stakeholders increasingly expect them to take stands, or even direct action, on major societal issues. But with new issues presenting themselves with ever-increasing speed and complexity—and with a political backlash to corporate activism mounting—even leaders with the best intentions can’t afford to make ad hoc decisions based on limited data or intuition alone. The age of corporate activism demands a clearly defined and structured corporate capability .

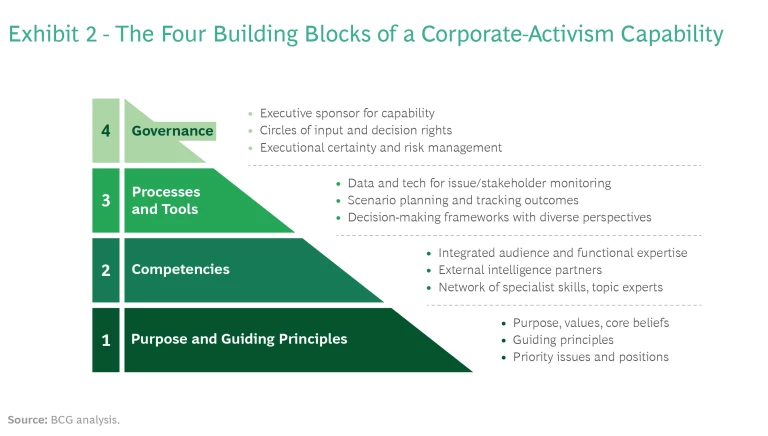

This is true whether you are a CEO energized by the opportunity to broaden your impact on society or one who is proceeding with caution and some reluctance—or if you’re somewhere in between. A corporate-activism capability should include four key elements:

- A clearly articulated purpose and a well-reasoned set of guiding principles

- The ability to draw on the right competencies, including in the areas of strategy, HR , public affairs and communications, customer insights , operations , and risk management

- Tools and processes for establishing positions on key topics, monitoring and analyzing issues and stakeholder sentiment, and evaluating options for the degree of engagement

- Rigorous but nimble governance, including clarity on who manages the work of tracking and assessing critical issues, who makes which decisions, and how delivery on commitments will be ensured and tracked

Building a corporate-activism capability is not about creating an entirely new department, nor is it about creating an additional layer of bureaucracy or pushing for decision making by committee. While its exact shape will depend on the company’s size, global footprint, engagement approach, and other factors, the capability should have a clear leader—typically an existing member of the company’s executive leadership—and a small, focused central team to drive the day-to-day work. That team will draw upon other leaders and groups across the organization, using streamlined processes and tools for rapid decision making.

Of course, none of this will serve as a substitute for the judgment of the CEO, the board, or whomever else might be making the critical decisions. Corporate activism can’t be reduced to an algorithmic approach, after all. But whether they are trying to be champions for change or to maintain a lower profile, leaders will be empowered by a corporate-activism capability—one that supports them in making decisions that align with the organization’s purpose and increase stakeholder trust.

Why You Need a Capability

In the not-so-distant past, a relatively limited number of companies engaged directly on societal issues. These days, however, just about every large company is expected to do so. At the same time, the set of societal issues that companies must face has rapidly expanded, spanning from climate change to abortion to the war in Ukraine. And additional issues are likely to land on the agenda soon. (See Exhibit 1.)

With all of this comes a significant increase in complexity. For one thing, different issues likely require different approaches. A company may simultaneously want to catalyze societal changes related to issue A, be a champion for issue B, and participate in issue C without much fanfare, all while remaining a bystander on yet another issue. As a result, each decision requires its own consideration of how the issue aligns with the company’s purpose, business interests, and stakeholder expectations, and the degree to which the company is likely to achieve its desired outcome while mitigating downside risks. (See “The Factors Driving Engagement.”)

The Factors Driving Engagement

First, how does the issue align with the company’s purpose, business interests, and stakeholder expectations? Among the factors to consider:

- Alignment with Purpose and Mission. Does the issue directly relate to the crux of why we exist and what we’re trying to accomplish?

- Alignment with Core Business Interests. Does the issue directly or indirectly impact a key lever of our business—such as profit and loss, talent, brand, supply chain, innovation, location, or stability?

- Alignment with Stakeholder Expectations. Are our stakeholders impacted? Do they trust and/or expect us to engage? How? Where are expectations misaligned?

- Ability to Impact or Influence the Issue. Does engaging align with our core competencies? Do we have reason to believe that we could contribute to achieving our desired outcome?

- Risk of Blowback or Negative Impact. What are the second- and third-order implications of engaging? Are we comfortable with the backlash we might receive from stakeholders and the media, including in other regions? What is the potential for negative impact, whether reputational, legal, political, or cultural?

- Creation of Commitment and Precedent. Can we realistically fulfill our commitments over the short and long term? Are we comfortable with the implications of setting a precedent by engaging?

In addition, as the number of issues grows, stakeholder and risk management become thornier and carry greater risk, even for those companies that are most comfortable with engaging. The current political environment in the US is perhaps the most obvious example. Governors and attorneys general in some states are pushing back aggressively on firms that embrace ESG investing, dubbing the approach “woke capitalism.” This debate around business’s role in society has only intensified in the runup to the midterm elections.

Even without those tricky political cross currents, the risk-management challenge grows more daunting as the set of potential issues expands. A stakeholder group that applauds an action in one area may, as a result, have higher expectations of action in another area. And a stakeholder group that is angry about action in one area may be more sensitive to positions or stands in another area, compounding the risk of blowback. Ultimately, missteps erode trust in the company, leading to strained customer relationships, increased regulatory scrutiny, employee recruitment and retention challenges, and even reduced market valuation. And CEOs who mismanage these issues put their own jobs at risk.

A corporate-activism capability isn't just about managing risk—it's about seizing opportunities.

That’s why a corporate-activism capability is so essential. It will allow companies to not only manage the risks that come with engagement but also seize the opportunity it presents. A capability will also enable companies to build better alignment around decisions—and that, in turn, will enhance their ability to mobilize people to deliver the desired outcome. In addition, companies may be able to identify and act on issues that they otherwise may have overlooked or focused on too late.

Ultimately, the capability can be a differentiator—giving the company an advantage relative to peers that have not brought sufficient discipline and rigor to their approach for engaging.

Developing a Corporate-Activism Capability

Most businesses have undergone new capability-development efforts before. Whether standing up a new corporate development team, creating centers of excellence in advanced analytics, or fostering innovation across multiple business units, new capabilities institutionalize a business’s ability to perform a critical function in a strategic and reliable way. Still, for a blossoming capability to mature and potentially become a competitive advantage, its development needs to be intentionally nurtured from the highest echelons of the company through deliberate design, planning, and investment.

That’s just as true for a corporate-activism capability. It should be designed to deliver a range of desired outcomes, including:

- Timely intelligence and assessment of key societal issues and stakeholder sentiment

- Prepared, yet evolving, internal positions on the issues

- Thorough and consistently applied criteria for corporate-activism decisions

- Clear decisions on the posture (in other words, the degree of engagement) the company wants to adopt on each issue

- The ability to rapidly secure internal alignment for corporate-activism decisions

- Clear and timely communications on positions and actions

- Rigorous risk management and mitigation of negative repercussions; equally rigorous monitoring of the company’s delivery on its commitments

There are four core building blocks of such a capability. (See Exhibit 2.)

Purpose and Guiding Principles. The foundation of a strong corporate-activism capability is purpose: a clear articulation of why the company exists, the role it plays in the world, and the way its authentic and distinctive strengths uniquely position it to play that role. That purpose should be embedded in the organization’s culture, strategy, branding, and actions; it also should ultimately translate into a set of commitments (explicit or implicit) to each of the company’s key stakeholder groups. If the purpose is both authentic and expansive, it will help the company identify and prioritize the key issues on which it will more proactively engage.

To make purpose an effective part of a corporate-activism capability, companies should also develop guiding principles that dictate how the company does or does not engage on issues. Principles should reflect an organization’s ethos and culture as well as its specific context with regards to geography, industry, and market position; such principles might be ethical in nature (“We do not lend support to dictator-led governments”) or process oriented (“We choose to engage in collaboration with others in our industry”).

Competencies. Effective corporate-activism decisions must draw from a range of expertise, skill sets, and perspectives—including strategy, HR, public affairs and communications, customer insights, operations, and risk management. Such decisions must also be based on input from those with deep expertise on the societal issues themselves—input that should be shared with decision makers, including the board, to build their understanding and awareness.

The relevant expertise and skill sets will differ somewhat by company and may shift depending on the issue at hand. In most cases, this expertise should be drawn from or developed inside the organization. However, sometimes competencies will need to be sourced externally, through targeted hiring, procurement (of experts or data, for example), or external partners.

Processes and Tools. Effective, streamlined processes are critical given the complexity of the issues that must be monitored and prioritized, the challenge of integrating the appropriate expertise, and the speed with which decisions need to be made. Processes need to be in place for a number of activities, including the tracking of hot-button issues and stakeholder sentiment; horizon scanning; scenario planning; discussions of whether—and how—to engage that include diverse perspectives and take such feedback into account when making a final decision; and the capturing of lessons learned based on outcomes from prior decisions.

The right tools, meanwhile, can support the teams and processes, ensuring rigor and consistency. Digital tools can be used to monitor and summarize possible future developments related to various issues and the intensity of stakeholder sentiment. Analog tools, including frameworks, templates, and scorecards, can be used to ensure decision criteria are applied consistently.

Processes and tools also need to account for the varying time constraints involved. For some decisions—identifying the issues on which the company will want to engage most aggressively, for example—it may be possible to deliberate over the course of months. But for others—such as responding to the January 6th US Capitol riot, for instance—company leaders may need to make a decision in a matter of hours.

Governance. Finally, a corporate-activism capability needs to clarify roles and responsibilities, particularly around when and how decisions are made and how to ensure that risks are managed appropriately. This governance structure should cover a variety of factors, including:

- Which executive is responsible for managing the work, and what kind of team is needed to support that executive

- How various perspectives are integrated and synthesized into recommendations

- Who ultimately reviews those recommendations and makes a final decision

- How governance changes in the event of more time-sensitive decisions

- How various kinds of risk are managed and mitigated

- How progress is monitored, with course corrections as needed

- How the feasibility of meeting commitments is assessed, and how the elements are put in place to deliver on those commitments

For example, a cross-functional team within the company may be tasked with monitoring developments, synthesizing findings, and preparing briefings on emerging issues. An executive team may review the briefings and make a recommendation to the group or individual with decision-making power. While the CEO might be the ultimate decision maker for more time-sensitive issues, a board subcommittee may conduct regular reviews and make recommendations to the board for decisions regarding corporate-activism priorities, actions, risk mitigation, and learnings.

The Role of Intuition and Instinct. The insights and rigor enabled by a well-developed capability for managing societal issues are both powerful and necessary. Ultimately, however, these decisions will still almost always require a judgment call, drawing on the intuition, instinct, and moral compass of leaders.

This is no different from other critical leadership decisions involving strategy or mergers and acquisitions. But as in those other domains, corporate-activism decisions will be sounder if companies have the right foundational capability in place.

Thriving in a New Era

The expectation that companies will engage on societal issues—with the accompanying polarized scrutiny of company actions—will not abate in the foreseeable future. Nor will the risks, including those in the political arena. At the same time, the mix of issues likely to come to the forefront in the coming months and years is no less daunting. Corporate activism represents a seismic shift in what’s required from businesses and their leaders. And that has significant implications not only for CEOs, boards, and other leaders who are still building the muscle to master this new environment, but also for business leaders who have long viewed activism on societal issues as part of their mandate.

Now is the time for companies to be proactive and develop an organizational capability for corporate activism. Intuition and instinct, while essential, are not sufficient for managing the opportunities and risks related to engaging on the topics that challenge society today. A strong organizational capability will enable companies and leaders to get ahead of looming events and react with consistency, ultimately increasing the trust of their stakeholders.

The authors thank Ulrike Schwarz-Runer, Amy Rule, and Nicole Dillner for their assistance in the development of this publication.