Charging different prices is often fairer than charging everyone the same price. Companies should take steps to educate customers and win their support for this approach.

For most people, a fair price is a price others pay for a good or service. At the same time, most people also consider giving a lower price to certain groups—such as seniors, students, or low-wage earners—to be fair. How can these two perceptions of a fair price coexist in the same society?

Welcome to the paradox of fair prices.

When the Bruce Henderson Institute (BHI) surveyed more than 13,000 people in eight countries, it learned that people have a healthy tolerance for what economists call price discrimination—selling the same product or service to different buyers at different prices—as long as companies can justify it. The challenge for business leaders who want to vary prices fairly is that individuals’ perceptions of what is fair are numerous, nuanced, and often contradictory. Whether individuals perceive a price to be fair will depend on the product or service category, their age, where they live, what they earn, their political beliefs, and who the customer is (themselves or someone else).

Business leaders know that price variation can be more economically advantageous than using a one-size-fits-all model; the former allows companies to serve more customer segments and earn higher margins. Yet few leaders have considered that price variation can be fairer than uniform pricing.

The Many Sides of Fair Prices

Classical economic theory suggests that customers would judge whether a price is fair from a perspective of self-interest. It seems obvious that rational buyers would be in favor of lower prices when they are the primary beneficiary. But BHI’s research shows that while seniors and students both feel that their receiving lower prices is fair, individuals in other groups feel it is less fair for themselves to benefit from lower prices. Rural residents and city dwellers, for example, consider giving discounts to seniors, students, and low-wage earners to be fairer than giving discounts on the basis of where someone lives, even if they themselves would benefit.

Charging fair prices, not maximum prices, optimizes profits over time.

Most people will also tolerate price discrimination that works against their self-interest. This holds true when they feel they have some control over the prices they pay, such as by choosing where to buy, when to buy, or whether to join a certain organization. Rob them of this perceived control, however, and they may vehemently resist higher prices. Coca-Cola once proposed the idea of varying prices at vending machines according to changes in the air temperature on hot days. It scrapped the plan after encountering widespread resistance. The temperature is a condition that customers can’t control.

Classical economic theory also dictates that a company should serve its own self-interest and, thus, should never leave money on the table. But BHI’s research reveals that leaving some amount of money on the table—by charging prices that customers perceive to be fair—is usually more in the company’s self-interest than claiming all the value in a transaction for itself. Charging fair prices, not maximum prices, optimizes profits over time.

Another side of the paradox is that discrimination—a negatively loaded word usually associated with harm—can be a force for good. The history of prices for air travel shows that price discrimination can be beneficial to customers, companies, and society. Adopting yield management enabled airlines to vary prices significantly from passenger to passenger on the basis of various reservation parameters, such as the timing of a booking. This form of price discrimination democratized air travel because it opened up greater access to consumer segments that previously couldn’t afford it or never viewed it as an option. Air travel’s growth would not have been possible on the same scale if airlines had consistently charged all passengers one uniform price to fly from point A to point B.

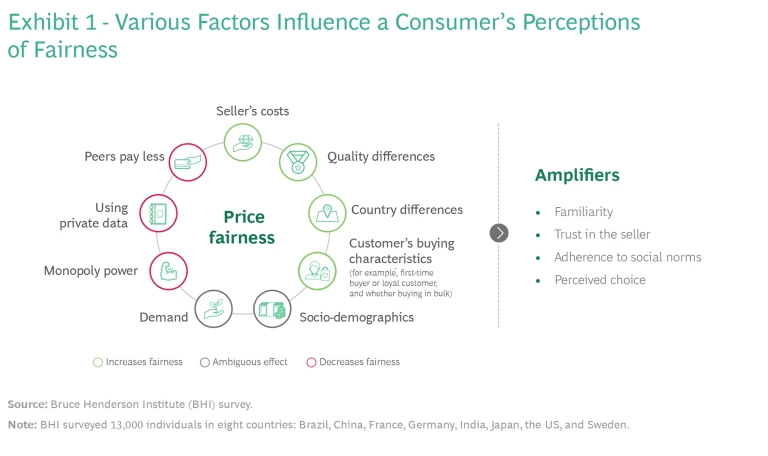

Adopting price variation is easier said than done, though, because various factors influence buyers’ perceptions of fairness. (See Exhibit 1.) For example, every society has its own ideas about what justifies price variation given its culture, norms, and history. These justifications are not always in sync with classical economic theories. Nonetheless, business leaders have a significant opportunity to embrace price variation by aligning their prices with established rules of fairness and communicating transparently and explicitly about why they are varying their prices.

The Many Nuances of Fair Prices

Let’s take a closer look at price discrimination that favors seniors, students, or low-wage earners—three groups that tend to face physical, social, or financial hardships.

Most societies—whether in the developed or developing world—consider it to be fair for seniors to pay lower prices. In the US, seniors can get discounts at several national chain restaurants starting at age 55, and even deeper discounts if they are a member of AARP, which one can join at the age of 50. Such age-based price discrimination often comes together with time-based discrimination. Several restaurant chains typically offer senior specials on Sundays or Wednesdays, while the chain Golden Corral varies prices for seniors by the time of day with its early-bird discounts.

But the senior discount is not an anything goes, blanket rule. On average, survey respondents from all countries consider it fair to offer seniors discounts for groceries, medications, and some forms of entertainment, such as movies, but only respondents in Sweden and the US broadly accept the idea of offering seniors a discount on most goods and services. The French and the Japanese are the most selective about the areas for senior discounts, perhaps because they have different traditions and more robust programs for supporting seniors.

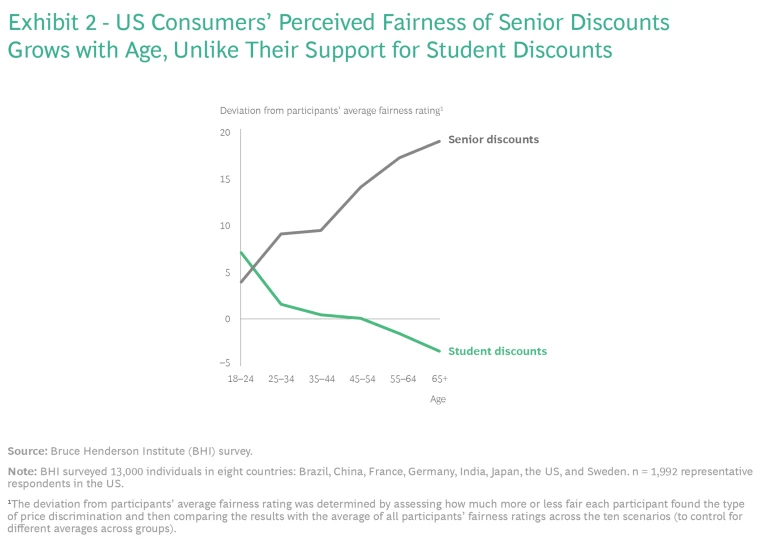

What do seniors think about their discounts? In the US, the older the seniors get, the fairer they feel their discounts are. (See Exhibit 2.) But they show much less enthusiasm for lower prices for students.

Such a contrast is important, because in some countries, students receive price breaks that are almost comparable to those given to seniors. The student identification card is the powerful key that unlocks steep discounts on a wide variety of goods and services, including computer hardware and software, train tickets, clothes, and furniture, as well as movie tickets and entertainment events. The presumption is that students also deserve a financial break because they are already bearing the expense of college tuition and room and board.

Most participants in our survey consider discounts offered to low-wage earners to be fair under certain conditions. One of many examples is the Affordable Connectivity Program, a new US government initiative that extends the Emergency Broadband Benefit (EBB) program and subsidizes high-speed internet access and basic computer hardware for low-income families. The EBB took effect in May 2021, and more than 11 million households had signed up by April 2022.

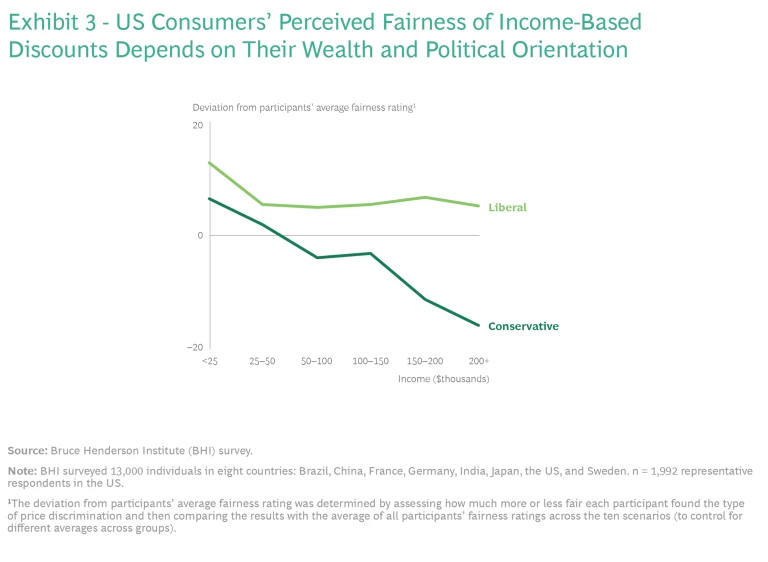

How fair are lower prices for internet access? That, of course, depends on whom you ask. BHI’s research shows that people in developed countries tend to consider offering lower prices for internet access to be reasonably fair when they benefit low-income families. But that picture becomes more nuanced when one looks at political beliefs and wealth. (See Exhibit 3.)

In the US, liberal-leaning respondents consider income-based discounts to be fair, regardless of their own income, while most conservatives find such discounts to be increasingly unfair as their income rises.

BHI’s research also underscores the point that perceptions of fair prices are on a spectrum. Practices can be fair, less fair, or unfair, with the caveat that the reaction of consumers is usually asymmetric. Making a fair price slightly fairer may bring little incremental benefit, while even slight missteps in terms of unfairness can draw a strong negative reaction from consumers.

Three Recommendations for Solving the Paradox

The insights from BHI’s survey offer business leaders an opportunity to step back and think about fair prices more consciously and deeply. We offer three recommendations.

Embrace price variation. Price discrimination is a strong and significant pricing lever that business leaders should use more confidently. They have a lot of latitude in most societies to vary prices in ways that the majority of people will perceive as fair.

This has several implications. First, a fair price is not synonymous with an equal price for all. That does not mean uniform prices are per se unfair. Uniform prices make practical sense, for example, for low-margin products when customers’ individual willingness to pay clusters around one value or lies within a narrow range. But as the perceptions of value widen—and, thus, the variance in willingness to pay increases—companies have a greater incentive to vary their prices. They can stop searching for the ideal uniform price and, instead, look for price variations that benefit both customers and the company.

Leaders have latitude in most societies to vary prices in ways that most people will perceive as fair.

In such an environment, implementing an advanced form of personalized pricing known as progressive pricing becomes desirable and feasible on a large scale. Rather than sticking to a single price for all customers, companies using progressive pricing charge higher prices to customers who place a higher value on a product or service and lower prices to those who place a lower value. The more accurate a company’s insights are into customers’ value perceptions, the better it can fine-tune prices at a personal level.

But the leeway to vary prices has limitations. The challenge for business leaders lies in respecting all the subtle, significant differences across countries, populations, and industries—usually tied to local customs and social norms—that allow multiple, often conflicting perceptions of fair prices to coexist.

Be accountable for the company’s justifications. Price variation works to the benefit of buyers and sellers when the buyers believe that the justification for the variation is valid. That means that price variation requires a communication strategy that makes the justifications positive, transparent, and explicit. These justifications can focus on aspects such as the differences in cost to serve or the various behaviors that buyers themselves can influence. Buyers also generally accept membership in a customer loyalty program or participation in a buyers club as reasons that justify why some people may receive lower prices.

Price variation works when the buyers believe that the justification for the variation is valid.

Using supply and demand imbalances to justify price discrimination is a more sensitive area for consumers. They generally accept supply and demand as a valid argument when price differences are relatively small—in the range of 20% to 25%. But when companies try to use the argument to justify extreme price differences (say, of 100% or more), it leads to accusations of price gouging, which not only angers customers but also makes them skeptical of the supply-and-demand argument.

Sometimes the justifications for price variations are implicit in a culture. BHI’s survey shows that in most countries, discounts for seniors need no explanation. The story of airline ticket prices, however, illustrates how consistent education over time is necessary to help customers understand the nature of price differences when established norms offer little or no clear guidance on what a fair price is. Repeated exposure to the reasons for the price differences—which include advance booking, loyalty program status, booking class, and departure time—means that many passengers can now figure out on their own, without emotion, why the person seated next to them may have paid 50% more or 50% less for their ticket to the same destination.

The vast increase in price transparency has also heightened the importance of having a strong and explicit justification for price differences. Historically, many companies have hidden price variation behind opaque practices that take advantage of consumers’ lack of awareness. Nowadays, consumers post about what they pay, and they can find and compare prices more easily than ever. A clear story that explains the reasons for price variations can turn transparency into an advantage.

Leave some money on the table. Business leaders seeking to charge fair prices should view leaving money on the table as an opportunity to seize rather than a mistake to avoid. No company should claim all the value it generates, because that would leave no value for customers. How much value it should share with customers depends on the strength and uniqueness of its value proposition, but it also varies by country, customer demographics, product characteristics, and whether the product is a big-ticket item or an inexpensive purchase.

A company with an unmatched value proposition has more leeway to vary prices and to claim a higher share of the value (more than 50% is possible), while a company with a me-too or a commodity product may claim significantly less than 50% of the value (and it can be as low as 5% to 10%).

What is a fair price? That has become a vitally important question in today’s era of transparency. Customers have the means and motivation to share and compare prices directly, and companies have the means and motivation to personalize their prices so they are in line with the measurable value they provide to individual customers.

While there are no standard answers to the question, business leaders can embrace market transparency, understand what drives the perceptions of fairness in their market, and ensure that they offer prices that customers will perceive as fair. With the right understanding and the right approach, companies can vary prices in ways that mutually benefit themselves and customers, and perhaps society as well.