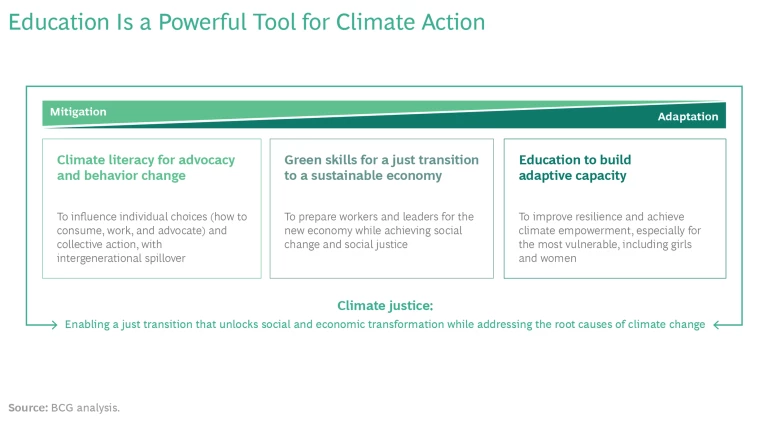

Education is a powerful means of spurring behavioral change and collective action, cultivating green skills, ensuring a just transition to a sustainable economy, and building communities' adaptive capacity.

More than 130 countries are aiming for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Technological innovations will be critical to reaching this goal, but achieving and sustaining net zero also require learning how to live on this planet as the climate rapidly changes—and education is a key enabler of this transition.

Education is a powerful means of developing the climate literacy that behavioral change and collective action require. It can also cultivate green skills and help ensure a “just transition” to a sustainable economy so that no group is left behind. Finally, education can build the adaptive capacity and resilience of communities. While there has been some momentum in each of these areas, more funding and greater scale and coordination of activities are needed.

We believe that education—often overlooked as a factor in reaching these goals—must become a more central theme in climate discussions and that the education sector needs to ratchet up its own ambitions to spur climate justice. (See the exhibit.) There is no time to waste.

Developing Climate Literacy

Behavioral change at the individual and household level—in choosing modes of travel, what to eat and drink, and how to heat and cool one's home, for instance—can contribute meaningfully to holding global warming to 1.5° C above preindustrial levels. And education can help spur those changes. By increasing students’ awareness and understanding of climate change and climate action , schools can empower young people to become agents of change in their local communities, instilling new norms and inspiring a sense of the possible. Early studies suggest that once young people become climate literate they help educate their families, which has a multiplier effect on their communities.

What’s Needed?

To accelerate climate literacy, educators, educational institutions, and governments must commit to implementing curricula that are action oriented (as opposed to merely being disseminators of information) and to training teachers accordingly. For example, the Green Schools Programme in India empowers teachers and students to deploy climate action projects in their local communities; elsewhere, Italy and New Zealand (and soon, Mexico) have committed to formally integrating climate literacy into national curricular requirements.

In parallel, schools must invest in greening their own infrastructure (from transportation to meals to energy use) so that they can lead by example while offering experiential learning opportunities for students. Organizations such as UndauntedK12, Let’s Go Zero, and the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education are working to encourage climate-friendly school infrastructure in the US and UK—and these are just a few examples.

Researchers should also rigorously evaluate the spillover effects that developing climate literacy has on the broader community in terms of advocacy and behavior change. More research is needed, but early studies suggest that school districts are near optimal size to scale climate action at the local level, making them a potent tool for broader community engagement and empowerment.

Cultivating Skills for a Just Transition

As economies transition from "brown" to "green," education can equip today's workers through reskilling and continuing education while laying the groundwork for those who will fill (and define) the jobs of tomorrow. This is critical, for without the skilled workers needed to scale innovations, the transition to a green economy could be delayed (the current shortage of qualified wind turbine technicians is an example).

The stakes are high. A just transition—which ensures that no group is left behind or left to shoulder an unfair burden—could deliver millions of new jobs in sustainable economies . Failure, on the other hand, could result in structural unemployment, undermining public support for climate action and fomenting social unrest. In fact, it is estimated that without reskilling, nearly 77 million jobs could be at risk globally—although that risk will vary significantly by industry and geography. Moreover, it’s important to remember that reskilling is critical not just to developing the skills needed for green jobs (such as in green energy) but also to ensuring that displaced workers acquire skills that will be useful elsewhere in a greener economy. Finally, this transition is an opportunity to ensure that those shut out of particular jobs because of gender bias or disability, for example, are included in the development of a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workforce.

What’s Needed?

To facilitate a just transition to a sustainable economy, education, government, and industry leaders must adopt an expansive view of green skills and climate literacy that includes both the technical and the leadership skills that the future demands. Leaders need to take a data-driven approach to understanding the skill requirements of a greener economy and align educational programs and training institutions accordingly. Partnerships among education, government, and industry need to focus on ensuring that everyone, especially those from historically marginalized groups, has the necessary skills and pathways to a good job.

Take, for example, the Greater Houston Partnership’s Energy Transition Initiative, which is proactively assessing the green-skills gap and working to ensure that the local education system is prepared to fill it. South Africa’s National Business Initiative has likewise worked to map sector-by-sector requirements (in the power, mining, petrochemical, and other industries) for a just transition, the impacts on jobs, and the reskilling programs required. Although the specifics of each industry and region’s transition will differ, stakeholders can and must learn from each other as they seek to tackle this challenge.

Building the Capacity to Adapt

To date, many investments to improve adaptability and resilience have focused on infrastructure. But given unpredictable climate patterns, these investments could lock countries into strategies for coping with climate change that prove insufficient.

We believe that greater investment in education, especially for girls and women, is a critical means of enhancing adaptive capacities over the long term. Women are often closest to many of the key levers for climate-related behavioral changes, such as in water usage, farming techniques, and cooking and heating habits. Investments in women’s and girls’ education offer the potential dual benefit of furthering climate action while increasing overall social equity. In fact, one study projects a 60% lower death toll from extreme weather events between 2040 and 2050 if 70% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa receive a secondary-school education.

Improvements in adaptive capacity are possible even when education does not explicitly address climate topics. Through increased literacy and economic opportunity, vulnerable populations are better equipped to respond to climate-related challenges, such as floods that force them to move or poor harvests that require them to find other work. Some organizations have begun to recognize this correlation, such as the Campaign for Female Education (Camfed) and the Green Climate Fund, which is funding Save the Children’s educational work.

What’s Needed?

To build a stronger case for educational investment, more research is needed to demonstrate the link between education and improved adaptability, resiliency, and economic opportunity. Increased evidence for and awareness of education's potential could strengthen countries’ National Adaptation Plans and unlock more flexible intersectional funding.

Education can have a transformative impact on climate action. It empowers students to reduce and respond to the adverse effects of climate change and to bring what they learn in the classroom to their communities. It gives workers the skills necessary to thrive in a green economy. It equips leaders to implement the next tier of climate innovations and to navigate a just transition. And it enables citizens to use their voice, consumer power, and political support to drive climate action. The time is now to unleash the power of education in promoting climate action and justice.

To learn more about the power of education in climate action and justice, see our full report, Education for Climate Action .