Do investors reward green dealmaking with higher returns in the shorter and longer terms? The answer is crucial to companies that are defining their M&A strategy for the coming years. Green dealmaking is gaining steam as a tool to support environmental transformations, but these deals often command a substantial premium.

A recent BCG study finds that green deals generally create more value than nongreen deals upon announcement and over the ensuing two years. At a more granular level, however, the industry, region, boldness of the deal, and characteristics of the parties are important variables. Although the findings paint a complex picture, the message is clear: companies that use the right approach to green dealmaking generate higher returns.

Performance Varies by Industry and Region

Our analyses focused on two metrics:

- Cumulative abnormal return (CAR) over the three days before and the three days after a deal announcement, to measure the short-term impact on share price

- Relative total shareholder return (rTSR) over 12- and 24-month periods, to assess longer-term value creation

(For additional details, see “ How We Track M&A Activity by Year ”)

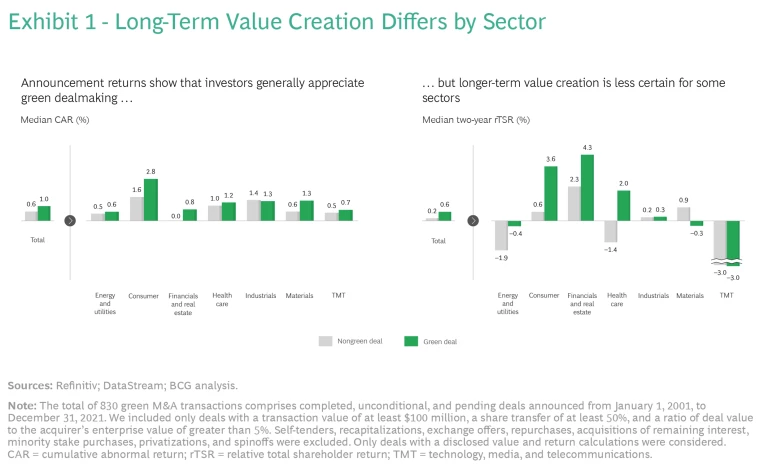

On an aggregate level, our analyses of both CAR and rTSR results found that green deals create value. The median CAR of environmental-related transactions (1.0%) is significantly higher than that of nongreen deals (0.6%). And over the longer term, the median two-year rTSR of green deals (0.6%) exceeds that of nongreen deals (0.2%). At the industry and regional levels, however, the situation is more varied. (See Exhibit 1.)

Some Industries Struggle to Create Long-Term Value

At the industry level, green deals create value at least as well as nongreen deals do. Announcement returns indicate that investors generally appreciate green dealmaking. However, longer-term value creation differs substantially across sectors.

Energy and Utilities. The energy and utilities sector warrants close attention, given that companies within it account for a significant portion of all green deals across industries. In this industry, green deals outperform nongreen deals over both time periods we analyzed. This likely reflects the fact that buyers acquire clean-energy companies (such as renewable fuel manufacturers and wind farm operators) or providers of efficient waste treatment or recycling services—businesses that have synergistic value for energy and utilities players, especially in light of the increasing urgency to employ greener business practices. Nevertheless, our findings carry some caveats. Although CAR is positive for green deals, it is below the median across all industries. Companies in this sector may be getting a smaller announcement bump because green deals are more common. More strikingly, the two-year rTSR for green deals is negative, albeit significantly less negative than for nongreen deals. Evidently, although investors generally favor companies in this sector that actively manage their portfolios through M&A, acquirers are, on average, failing to create value.

Consumer Goods and Retail. In the consumer goods and retail sector , green deals significantly outperform nongreen deals in both CAR and two-year rTSR. Investors recognize that consumers appreciate the outcomes of green deals, including expanded offerings of organic products and greater use of environmentally friendly packaging. Because these outcomes potentially boost companies’ corporate image and sales, green deals generate higher shareholder returns. High-performing deals include Amazon’s merger with Whole Foods, a natural and organic supermarket operator, and Pinnacle Foods’ acquisition of Garden Protein International, a producer and wholesaler of plant-based protein products.

Financials and Real Estate. A similar level of outperformance for green deals is evident in the financials and real estate sector . For example, investors responded favorably to Intercontinental Exchange’s acquisition of Climate Exchange, a leader in the development of traded-emissions markets. They also generally like moves by asset managers, such as investment funds and private equity firms, to invest in green targets. For banks and asset-management firms , in particular, green deals clearly outperform nongreen deals in two-year rTSR, an indication of investors’ awareness that these institutions’ clients favor adoption of greener practices. The picture is less clear for insurance companies and real estate firms.

Materials. The higher CAR for green deals in the materials industry likely reflects investors’ positive view of environmental transformations or deals that provide access to so-called “future materials” enabling transitions to greener energy. On the other hand, the two-year rTSR for green deals is negative and lower than for nongreen deals. The challenges of longer-term value creation are evident for green deals across most of the materials sector, including in metals and mining , construction materials, packaging, and paper and forest products. Still, we expect that the imperatives to decarbonize operations and acquire new types of materials will motivate additional green dealmaking in the sector.

Technology, Media, and Telecommunications (TMT). For

TMT companies

, both green and nongreen deals have positive CAR but negative two-year rTSR. This may be due to the relatively small sample size for green TMT deals. It may also indicate that investors regard green transformations as less relevant for digital companies that do not have a large CO2 footprint.

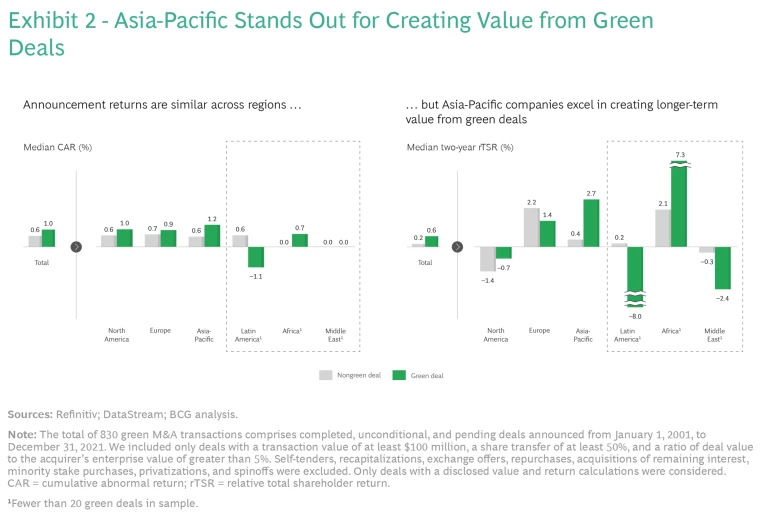

Asia-Pacific Companies Excel in Value Creation

Our regional analysis focused on acquirers from North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific. Analyzing the green deals of acquirers from Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East is difficult because data samples are so small (fewer than 20 deals with sufficient data in each region) that the results they yield are unreliable.

Our analysis of North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific found that investors react more positively to green deals than to nongreen deals upon announcement. (See Exhibit 2.)

Over the longer term, however, there is much greater variability:

- In Asia-Pacific, the two-year rTSR of green deals is significantly higher than that of nongreen deals.

- In Europe, green deals perform well, but nongreen deals have an edge, suggesting that European acquirers find it harder to create value from environmentally focused M&A.

- In North America, the average two-year rTSR across all deals is negative, pointing to significant challenges in value creation. Even so, green deals fare better than nongreen deals.

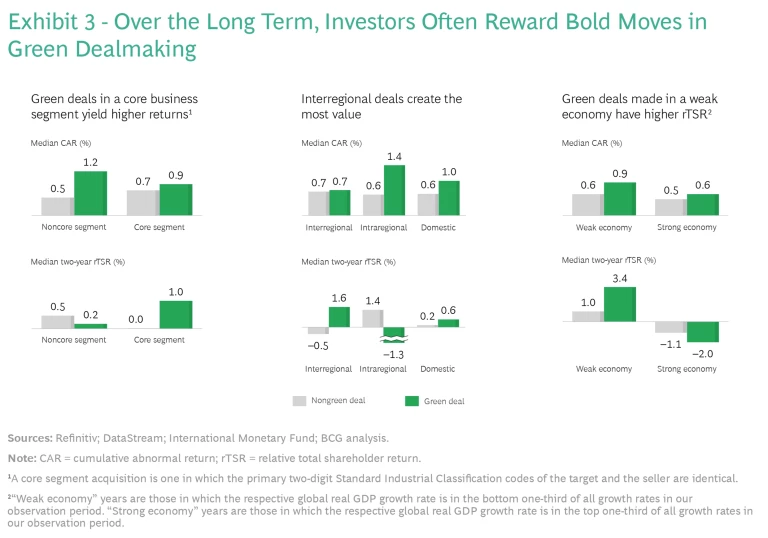

Bold Moves Often Create More Value

To delve further into the performance of green deals, we compared value creation in three contexts: core business versus noncore business, geographic reach, and economic conditions. (See Exhibit 3.)

Core Business Versus Noncore Business. Our analysis shows that acquisitions of core businesses—that is, target companies within an acquirer’s broader industry family—produced significantly higher two-year rTSR than acquisitions of noncore businesses. This is consistent with our previous finding that capital markets impose a “conglomerate discount” on diverse corporate portfolios . Over the short term, however, CAR is quite high for noncore green acquisitions. Capital markets seem to react favorably to the announcement of these deals, perhaps indicating that investors are initially impressed by bold moves to buy environmentally friendly assets outside the acquirer’s industry.

Geographic Reach. We examined domestic deals (both parties based in the same country), intraregional deals (for example, a US-based company acquiring a Canadian target), and interregional deals (for example, a French company acquiring a Japanese target). For all three types, green deals have higher CAR than nongreen deals.

Green deals in the domestic market, where acquirers are usually quite knowledgeable about local dynamics, have positive two-year rTSR, while intraregional deals have negative rTSR during this period. Surprisingly, interregional deals have the highest two-year rTSR, indicating that they are the most promising sources of longer-term value creation. This might be because boards and stakeholders more closely scrutinize such deals before execution. Collectively, these findings suggest that dealmakers should consider green targets not only in regions they know well but also in other regions. The additional scrutiny required when buying targets in unfamiliar regions may be rewarded with higher returns.

Economic Conditions. Regardless of economic conditions, investors initially reward companies for making green acquisitions. Two years after an acquisition, however, buyers’ rTSR is higher for green deals that were announced in a weak economy. Indeed, green deals announced in a strong economy have negative rTSR, suggesting that, during good times, acquirers may tend to overestimate a deal’s benefits or overpay for a target. In short, taking the risk of buying green assets in a weak economy seems to be a winning strategy, which is consistent with our broader research on dealmaking in downturns .

Both the Buyer and the Seller Matter

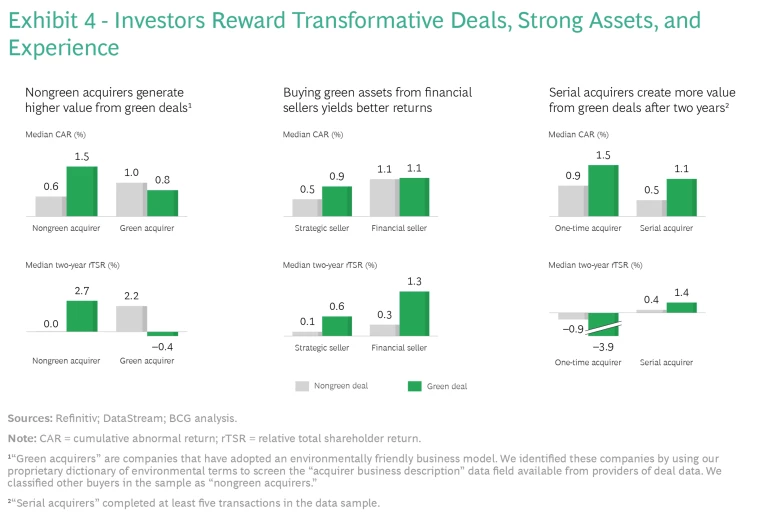

We also analyzed green deals from the perspectives of different types of buyers and sellers. (See Exhibit 4.)

Green and Nongreen Acquirers. Green acquirers are companies that have adopted an environmentally friendly business model. We identified these companies by using our proprietary dictionary of environmental terms to screen the “acquirer business description” data field that is available from providers of deal data. We categorized other buyers in the sample as nongreen acquirers. (See “ Defining ESG and Environmental M&A Transactions ” for a description of the dictionary.)

In environmentally focused transactions, nongreen acquirers realize higher CAR and two-year rTSR than green acquirers—an indication that investors reward nongreen acquirers for transforming toward a greener business model. For their part, green acquirers realize higher CAR and two-year rTSR when buying non-green targets. This might indicate that investors expect green acquirers to use their capabilities to transform nongreen targets into greener businesses—or at least anticipate that green acquirers will not be adversely affected by purchasing nongreen targets.

In the industrials and materials sectors, for example, the contrast is stark: nongreen buyers acquiring green targets realize positive one- and two-year rTSR, while green buyers have negative rTSR. We found a similar contrast in the energy and utilities industry—arguably the industry in which companies have the greatest need to acquire green assets. This suggests that value creation is highest when green deals have a transformative impact rather than merely reinforcing an existing green business model.

Financial-Investor Sellers. Buying green assets from financial investors generates more short- and longer-term value than buying them from a company—that is, a strategic seller. Capital markets recognize that financial investors usually sell businesses after they have improved their strategy and operations, among other aspects of performance. Strategic sellers, in contrast, are more likely to divest underperforming green assets while keeping those that are performing well.

Serial Acquirers. Strong returns from M&A are highly correlated with deal-making experience. Serial acquirers—those that completed more than five deals in our data sample—outperformed in two-year rSTR for both green and nongreen deals. One-time acquirers have higher CAR for all deals, but they underperform quite significantly in rTSR. Over the longer term, experience appears to make an even bigger difference in green dealmaking than in other deals: serial acquirers have a 5.3-percentage-point advantage in rTSR over one-time acquirers for green deals versus a 1.3-percentage-point advantage for nongreen deals. The message is clear: building expertise and a strong team of dealmakers is imperative, especially for green deals.

Across our analyses, investors recognize the value-creation potential of green deals. But while many dealmakers create value from green M&A in the short and long terms, others struggle to succeed. In green dealmaking—perhaps even more than in other transactions, success requires a well-defined M&A strategy that is integrated with the overall corporate strategy and informed by experience. In the next article in this series, we explore the winning moves for green M&A.

The authors are grateful to Ashish Baid of BCG’s Transaction Center and to Miriam Benedi Díaz, Sonja-Katrin Fuisz-Kehrbach, and Benedicte Montgomery of BCG’s Climate & Sustainability practice for their valuable insights and support in the preparation of this article.