Despite its merits, net zero isn’t a perfect mechanism for addressing climate change. Here are 15 of its limitations—and our recommendations for fixing them.

“The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is now.” — Chinese Proverb

The growing number of companies making net-zero carbon commitments offers a ray of hope for progress on climate change. Currently about 33% of world’s largest companies and more than 50% of countries have pledged to reach net zero, with target dates varying mostly between 2030 and

More commitments will almost certainly follow. As one company moves, others in the industry feel pressure to follow—either to avoid being seen as a sustainability laggard, to fend off regulatory requirements that might be more stringent, or to build advantage in a shifting competitive landscape. A single company with the

courage to set ambitious targets

can ratchet up the efforts of an entire industry while seizing early advantage. As of October 2021, virtually all of the world’s airlines had pledged to reach net zero by 2050, having previously promised only a 50% net reduction in emissions in

Net zero has become the gold standard for government and corporate commitment on climate change. But is this increasing focus on net zero sufficient to address climate change? If not, what else do we need to think about and act upon?

What is Net Zero, Exactly?

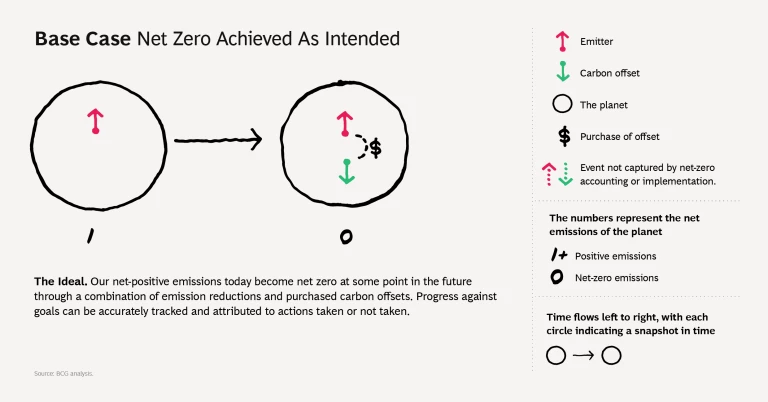

Net zero is an accounting mechanism that measures a company, country, or individual’s carbon footprint using an accepted standard.

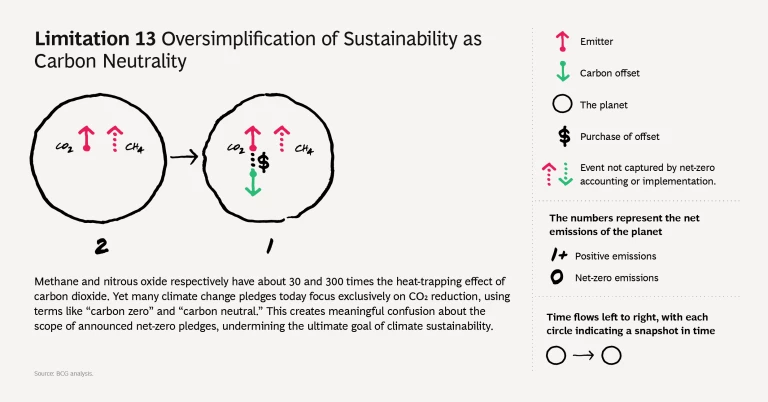

In the credits column are the metric tons of carbon dioxide and carbon dioxide equivalents (for other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide) that a company produces through the direct (Scope 1) and indirect activities (Scope 2) of the company as well as its supply chain (Scope 3).

In the debits column, emissions that cannot be immediately reduced by the company can be offset by paying someone else to take an equivalent amount of carbon out of the atmosphere. Such offsets can use both nature and manmade technologies to remove greenhouse gases, although the former predominate today. Common nature-based methods include sequestering carbon in plant matter by planting new forests, protecting existing ones, or restoring previously logged ones. Technological approaches include capturing greenhouse gases such as methane gas at landfills, nitrous oxide at chemical plants, and direct carbon capture from the air.

A company, country, or individual is said to be net zero when the debits equal the credits—meaning the entity is not contributing additive greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The idea is that if all countries, companies, and individuals become net zero, we end up at net zero for the planet.

The Impact of Net Zero

The net zero concept has some strong merits in facilitating effective collective action toward the goal of taming climate change. First and foremost, net zero provides a measure of transparency and comparability in accounting for carbon emissions. Little progress will be made overall without clear accounting and accountability for environmental impact.

Secondly, the scheme creates an easy way for companies and countries to make both long-term decarbonization commitments and create immediate impact. Companies can plan a realistic path for decarbonization while using offsets in the short term.

On its face, this should result in:

- Progress toward climate stability and a means to track it,

- A scalable mechanism for an increasing number of players to commit over time and peer pressure to encourage this,

- Reputational benefits for companies with consumers and procurement preference with B2B customers,

- Consumer engagement and contribution through support for brands with net-zero commitments,

- Reduction of risk for shareholders as the companies they have invested in adopt sustainable business models without abrupt disruption to short term returns, and

- Increased protection for nature, as most carbon offsets today are nature-based.

However, a closer inspection reveals that net zero also has some significant limitations which, if unaddressed, could easily misrepresent and undermine progress toward the ultimate goal of environmental sustainability.

Fifteen Important Limitations of Net Zero

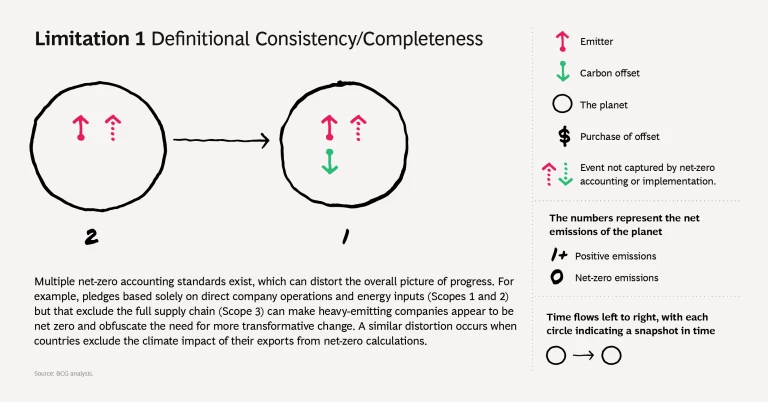

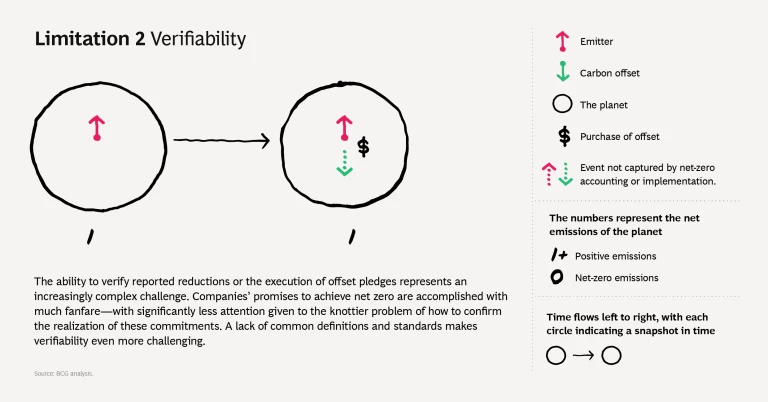

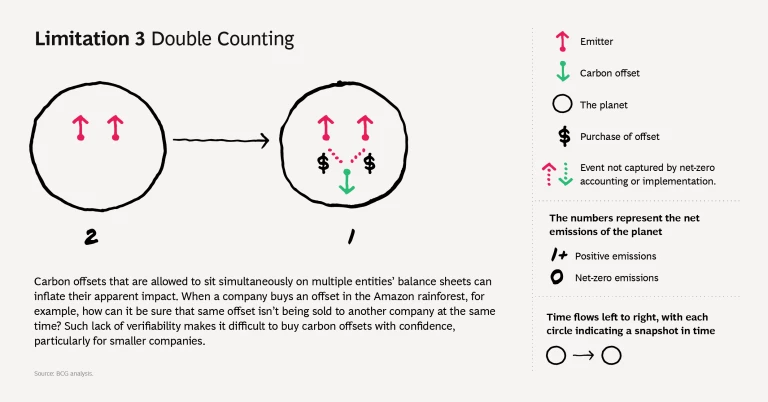

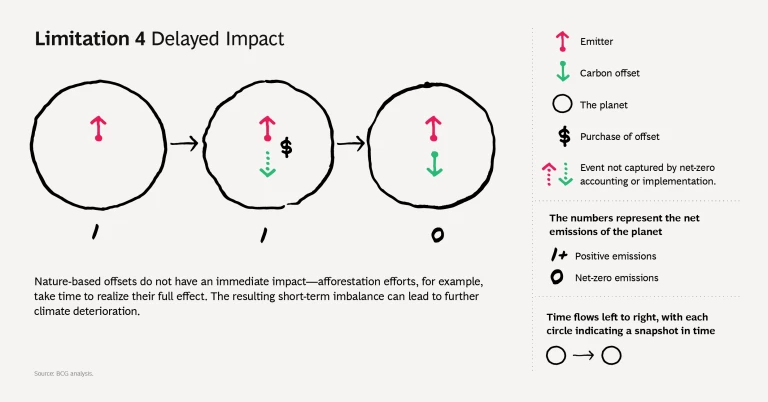

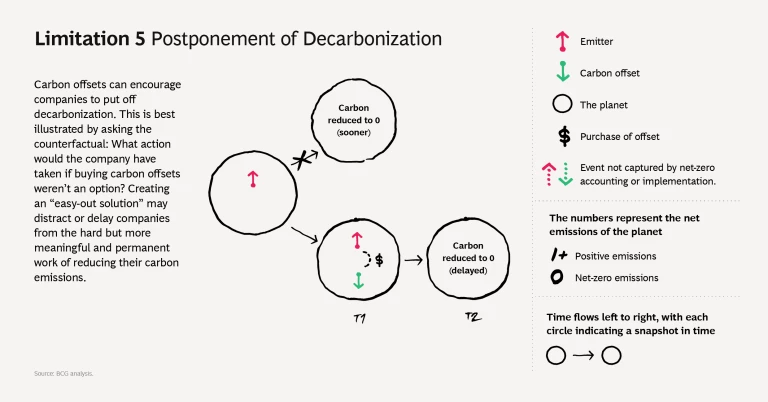

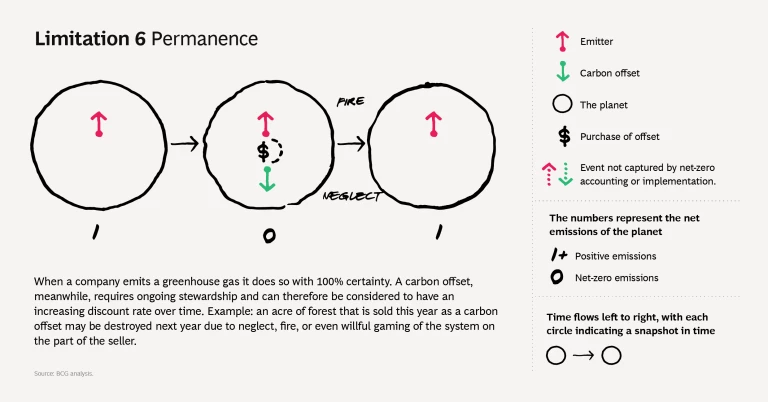

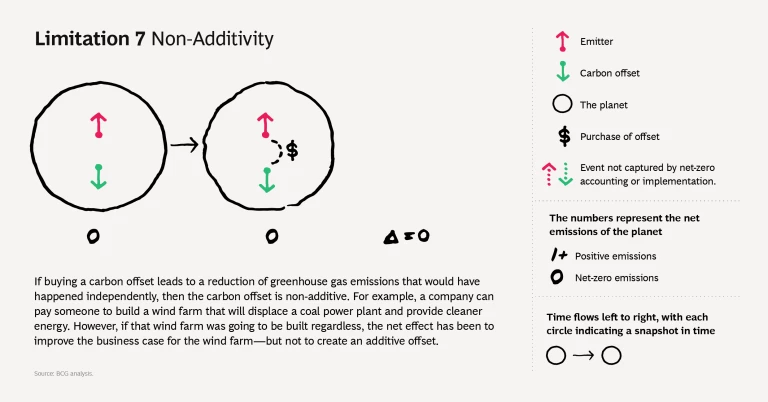

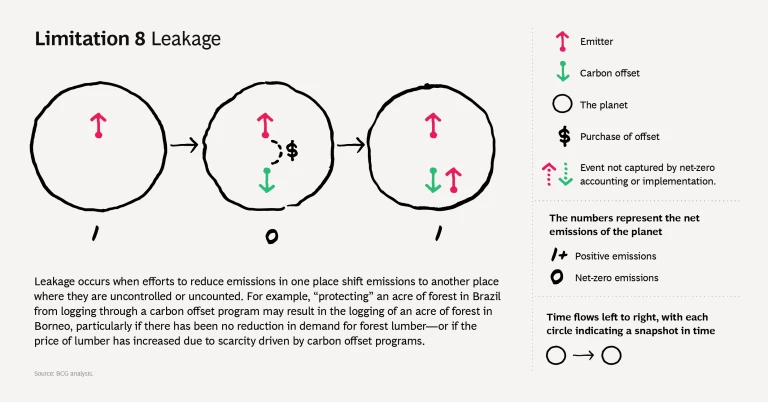

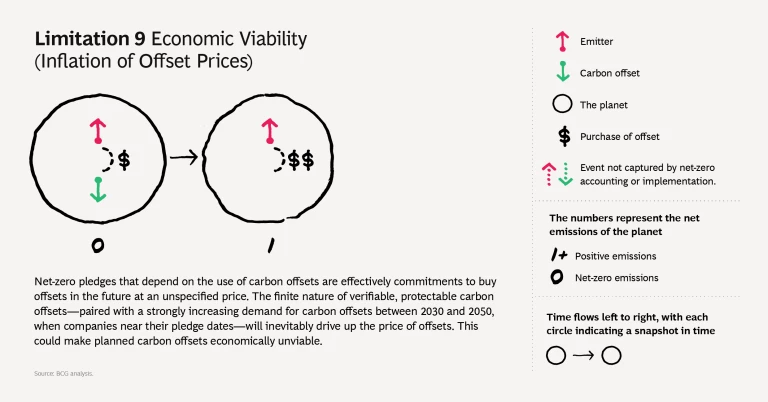

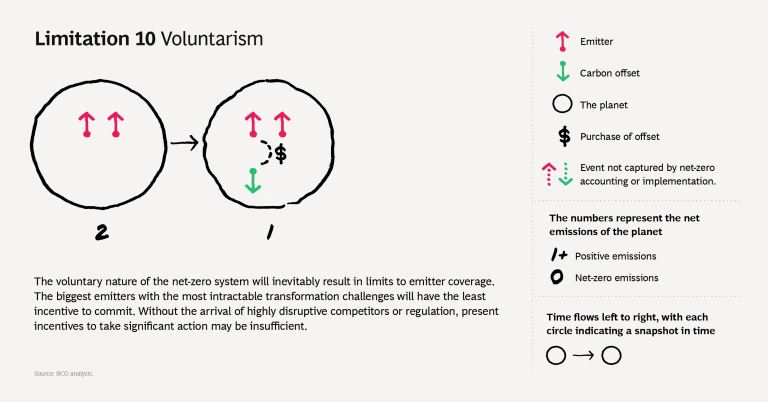

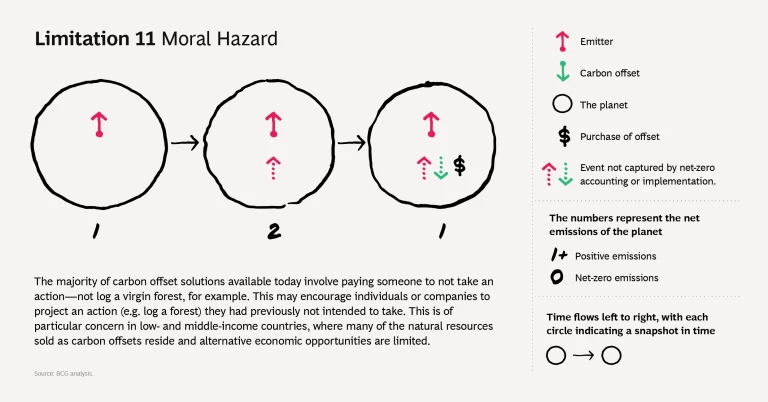

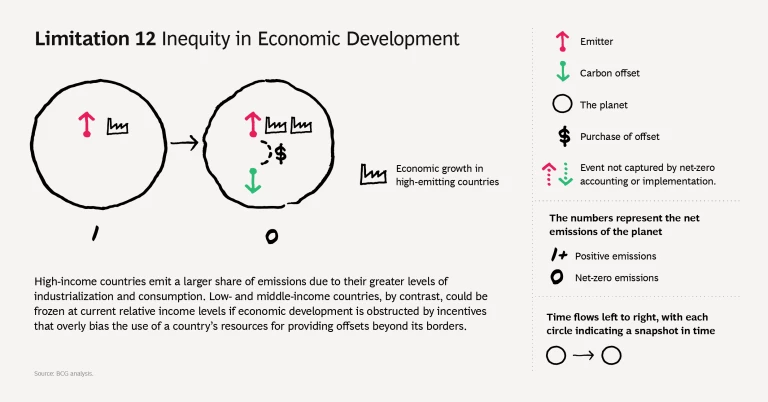

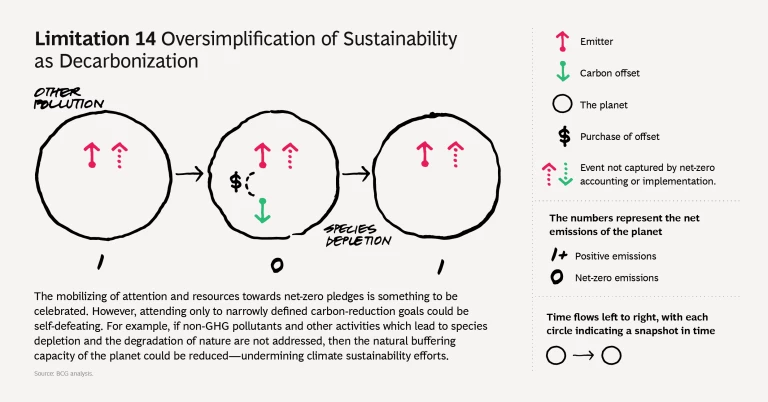

Notwithstanding the benefits mentioned, net zero has some significant gaps and limitations which need to be addressed to attain sufficient impact overall. We have captured these in a series of scenarios, all of which have examples in the present; each scenario captures a problem with definitions, implementation, or scope that can lead to emission reductions being postponed, exaggerated, or diminished. Taken together, these limitations could hinder decarbonization efforts, with net-zero pledges providing companies a false sense of accomplishment and allowing them to mistake activity for progress.

Elements of a Better Path Forward

Given these limitations, how do we best leverage the momentum created by net zero to evolve ever more robust solutions and pathways? We don’t pretend to have the complete answer, but some elements of a better path forward might include the following.

Enhancing Net Zero

Net zero provides a meaningful system of accounting and accountability and can be enhanced to remove some of these limitations. While definitions are continually being improved, sufficient attention also needs to be given to how they are applied in practice.

- Establish consistent definitions and standards. Net-zero emission targets must account for all GHG emissions of companies and countries, in all aspects of operations. While methane and nitrous oxide remain harder to address, their high impact necessitates that they are included. This should address the limitations of definitional consistency and completeness.

- Create mechanisms of verification. Audited inventories of carbon offset resources can be established to provide a means of verification, to eliminate double counting, to monitor permanence, and to help project the inevitable inflation in offset prices.

- Split out the reporting of—and accelerate—decarbonization. Carbon offsets cannot be allowed to substitute for or postpone addressing emissions, the root cause of climate change. Companies and countries should be required to report separately for emissions reductions and offsets. This should help address the problem of postponement.

- Accelerate commitments. Net-zero pledges in the distant future must be coupled with interim commitments. These are essential to increasing the sense of urgency, accelerating near-term action, and providing the ability to monitor progress and course-correct toward the ultimate target, which will help overcome the limitations of delayed impact and postponement of true reduction.

Moving Beyond Net Zero

In addition to enhancing net-zero mechanisms, we must pursue a more multidimensional view of

sustainability

and put in place the financial, operational, technological, behavioral, and cultural support to enable the transformative action necessary to achieve climate sustainability for the planet.

- Multidimensional view of sustainability: Consider sustainability beyond the single dimension of carbon emissions to include all relevant factors, including other GHG emissions, species diversity, air and water quality, and nature preservation. This multidimensionality can help to overcome the risks of oversimplification.

- Develop a behavioral strategy: While there is significant work underway to improve accounting, more work is required to understand the behavioral economics of decarbonization, so that the right nudges, sticks, and kicks can be used to direct human action in the desired direction and address the limitations of moral hazard and non-additivity. In particular, we need to harness the power of future regret to mobilize present action.

- Ensure sustainable economics for decarbonization and offsets. Plan for carbon economics to shift over time as demand for offsets and sustainable inputs create new scarcities and price inflation, to address the limitation of economic viability.

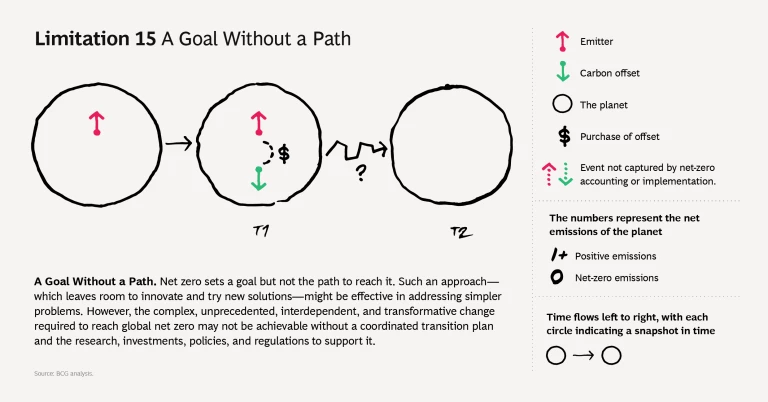

- Develop transition paths: Reaching net zero will necessarily require large-scale societal change. What are the major shifts economically, technologically, and societally that must be made? How do we act on and sequence these major shifts collectively, to provide the foundation for individual agents to meet their net-zero targets? This should address the limitation of goals without paths.

- Accelerate innovation: Decarbonization will require more, cheaper, and better solutions than we have today. We do not currently have the approaches to meet our commitments; as such, we must accelerate the rate of discovery, scaling, and deployment of technological and nature-based innovations through increased funding, private and public partnership, and international cooperation.

- Regulatory and fiscal policy: Regulatory and fiscal policy should be put in place to make corporate and societal transformation a viable path. Like a ball rolled down the street, the regulatory policy forms the curb—channeling the direction of the ball while the fiscal policy determines the decline of the street—providing the force to overcome friction and accelerating the path of the ball to its desired direction. Together, regulations and financial policy can help overcome the problems of volunteerism, leakage, and inequity of economic development to ensure that planetary net zero happens expeditiously, ubiquitously, and equitably.

Net zero has provided a positive foundation and engendered momentum critical for the fight against climate change. However, we must work together to enhance net zero by removing these 15 limitations—taking a more multidimensional view of, and approach to, sustainability. As more companies and countries make net-zero pledges, we must laud their commitments while continuing to ask for more.