Traditional projects offer varying returns, depending on an investor’s willingness to embrace risk. But all eyes are on digital.

Massive infrastructure funding recently approved by the United States, China, and the EU, as well as ongoing improvements in low- and middle-income countries, are placing a renewed emphasis on infrastructure investments. Indeed, fund raising for public and private infrastructure investments—which include everything from power generation and renewable energy facilities to schools, hospitals, digital networks, water resources, and transportation projects—is hitting fresh highs: in 2022, global assets under management of private infrastructure investors are forecast to reach a record $950 billion.

While infrastructure investment opportunities are rife, returns from these projects vary. Some investment strategies are well suited for big gains in today’s environment; others are designed for smaller, albeit consistent, returns. Given the many possible investment strategies and the growing popularity of infrastructure investments as a whole, BCG and EDHECinfra, a provider of indexes and analytics for infrastructure investors, have partnered on “ Infrastructure Strategy 2022 ,” the first in a series of annual reports intended to categorize the universe of investors by their priorities and focus as well as by their risk-adjusted performance.

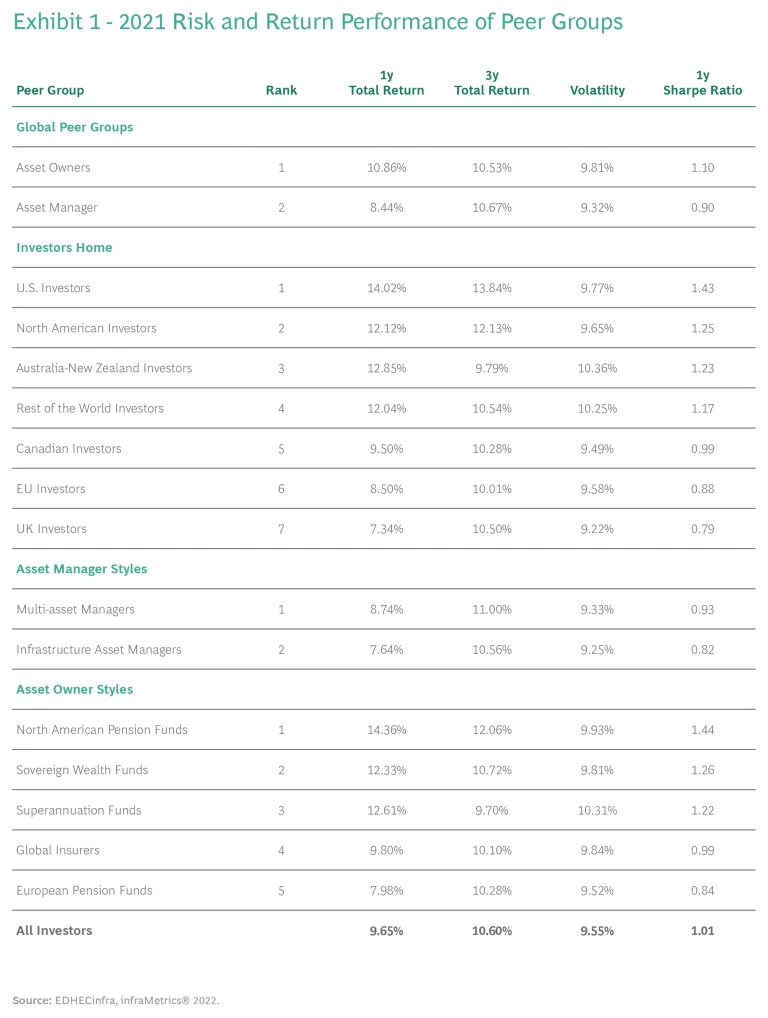

The centerpiece of this report is the division of infrastructure investors into 16 peer groups that can be further broken down into four categories: global peer groups (which include asset owners, such as pension funds, endowments, and sovereign funds, and asset managers, such as private equity funds); home regions; asset manager styles; and asset owner styles. (See Exhibit 1.)

How We Chose Peer Groups

We created the 16 peer groups by examining the portfolio allocations of 359 infrastructure equity holders—and ranked the groups by their risk-adjusted returns or their Sharpe

Through this lens, some noteworthy assessments about infrastructure investors and their strategies and tactics can be readily discerned. Chiefly, peer groups differ widely in investment exposure, risk tolerance, and portfolio focus. For instance, asset owners outperform asset managers in large part because they are less risk averse, with about 60% of their investments in merchant or regulated businesses (riskier because new rules, rating systems, and market conditions can impact their financial performance) and higher allocations in the riskier energy and water resources and transport sectors.

Peer groups differ widely in investment exposure, risk tolerance, and portfolio focus.

And among asset owner strategies, North American pension funds earned the top ranking by having a performance-focused portfolio, allocating more of their investments to merchant assets. The Australia-New Zealand and “rest of the world” peer groups (the latter being chiefly investors from Asia and the Middle East) also performed well because of exposures to riskier segments, although their mix includes significant exposure to transportation investments and less exposure to conventional energy supply and generation.

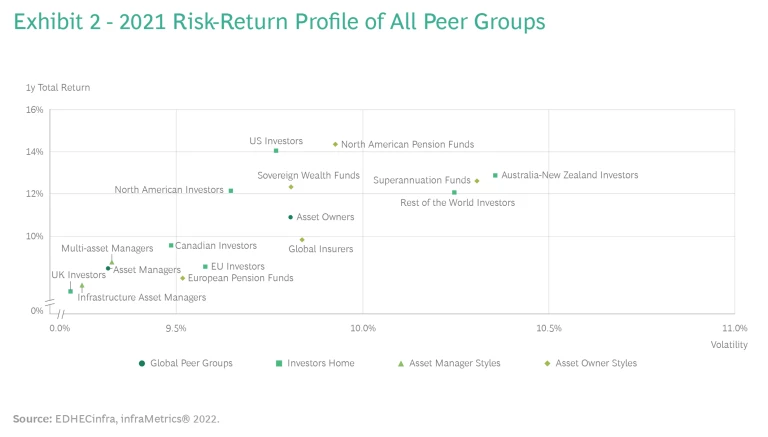

US investors have enjoyed some of the highest returns in large part because of their preference for merchant business models , such as power plants and transport companies. Contracted business models, in which the infrastructure providers have long-term agreements with the public sector or private companies to deliver specific services, are favored by European investors and did not perform as well. Importantly, while investors generally achieved higher returns by embracing risk (see Exhibit 2), different levels of volatility sometimes produced dissimilar realized returns. This is because the pace at which individual peer groups gained exposure to riskier segments of the infrastructure asset universe varied. For instance, superannuation funds took more risk but achieved lower average returns than North American pension funds.

Peering Into the Future

More than a window into the status quo, the survey also uncovered sharp shifts in infrastructure investment strategies that are likely to take hold in the relatively short term (meaning the next three to five years). For instance, the survey found that investor sentiment about the urgency of value creation is in flux. Although non-infrastructure equity investors typically view value creation as an imperative—in large part because stocks may be held for relatively short durations and need to increase in value quickly to generate gains—many infrastructure investors (though not all) historically have made value gains less of a priority. The thinking was that value on big infrastructure projects, such as major roads, would grow over longer periods, during which time cash flow would often provide a financial cushion.

Among the survey respondents, however, more than half of asset managers—across the risk-taking continuum—have already changed their minds about this and now view value creation as important. In addition, most of the minority that doesn’t see it that way still concedes that value creation will be important within the next five years. This change of heart is driven by the perception that infrastructure investments are already becoming more volatile, as evidenced by the recent steep increase in asset prices—a trend that will be exacerbated by inflation and secular shifts, such as the energy transition and digitalization. Consequently, basing an infrastructure investment strategy on hoped-for long-term returns, rather than consistent operational value creation, is not viable anymore—something that asset managers as well as direct investors, such as pension funds and their ilk, are keenly aware of now.

Basing an investment strategy on long-term returns rather than consistent value creation is no longer viable.

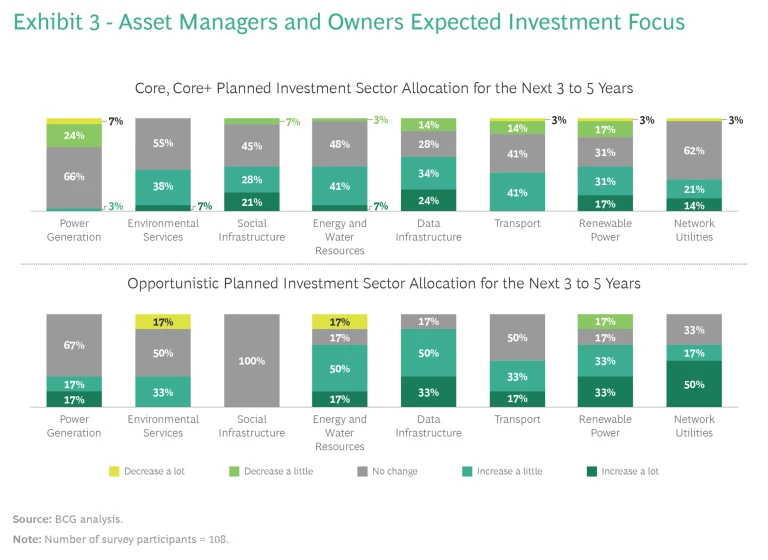

Digital infrastructure is not yet enjoying an essential position in investment strategies, but that too is about to change. Survey respondents said that their investment focus in the next three to five years will shift to digital and communications projects—which include everything from cell towers to software developed to manage operations in (for instance) construction or utilities—and move away from older investment sectors such as conventional energy and transport. (See Exhibit 3.)

In our view, the growing attractiveness of data projects will shine a spotlight on one category of investments in particular: fiber optics. The increasing desire for higher speeds and reliable internet connectivity will lead inevitably to a huge expansion of fiber optic installations around the world. Ultimately, fiber will replace legacy infrastructure (primarily copper) completely, especially as 5G rolls out.

Demand for fiber optic projects is spreading rapidly across the globe. In large and diverse untapped markets, such as Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Brazil, and parts of Asia, new digital networks that will rely on fiber optics are being developed. And in higher-income countries, fiber penetration remains uneven, with notable discrepancies among urban, semirural, and rural areas.

Eyeing this demand and the billions of dollars in government subsidies targeted at fiber installations around the world, fiber network companies—both designers and builders—are jumping wholeheartedly into the market, and they motivate investors to move funds also into public-private ventures involving fiber optics.

Strong Returns in Fiber Optics

A wide range of companies will play outsized roles in fiber rollouts, offering significant opportunities for infrastructure investment managers and investors. In our view, the dominant ventures that will lead fiber optic efforts can be broken down into four categories:

- Legacy telcos.

- Pure fiber companies (fibercos), which are newly created businesses established to bring fiber connectivity into unpenetrated areas, particularly rural regions, often as a joint venture between telcos and private investment funds.

- Network companies (netcos) carved out of legacy telcos, established to accelerate fiber rollout.

- Public-private partnerships, which are a good option for rural areas, with governments subsidizing these efforts in order to expand broadband into remote regions.

The strength and potential of the fiber optic market can be easily seen in the financial performance of companies involved in this sector as well as in their valuations as takeover candidates. In 2020, top businesses in this sector had enterprise value-to-EBITDA ratios (a well-regarded metric for assessing full market value) of well over 15, with a few as high as 27. In contrast, EV/EBITDA of classical telcos ranged from 6 to 9 with cable companies at the high end, integrated telcos in the middle, and mobile-only players at the lower end.

Keys to Successful Fiber Investments

With these valuations, new fiber optics projects could be a profitable opportunity for infrastructure investors who understand the fundamentals that drive the best returns. In our view, three levers drive return on investment (ROI):

- Optimized Fiber Network Utilization. To ensure that a new fiber project has the widest customer base possible, companies need to extend their retail and wholesale capabilities as far as is feasible. The goal should be to become the first and sole fiber optic provider in a region, selling access to other companies and discouraging competitors from taking on the huge capital expense of building their own network when, at best, they will be an also-ran.

- Low CAPEX Due to Operational Efficiencies. Capital expenditures on a fiber project can be reduced in the design and build stages by using the latest technologies, including AI-based automated programs, to plan the construction process and monitor each stage—with the goal of keeping the project on schedule and avoiding rework to fix mistakes or make up for deviations from the original plan. And since labor accounts for 80% of the costs in any CAPEX project, controlling worker costs is essential to deliver high ROIs.

- High Average Revenue Per Customer. The best pricing strategy to increase revenue per customer could be called “more for more.” That is, fiber companies must sell their copper replacements as an advantaged approach—more costly than copper but providing customers with more bandwidth, greater reliability, and customized service bundles.

The Infrastructure Strategy 2022 report was prepared to provide a new way of looking at the investment styles of infrastructure investors and to highlight the types of investments that are favored today—and those that will be preferred tomorrow. Faced with increasingly creative and technologically advanced projects, funding from the private sector and private investors will also expand in size, scope, and imagination.