Institutional investors were late to realize the alpha potential of clean tech and other environmental investments. They should avoid making the same mistake with social impact.

A decade ago, few institutional investors believed that their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) funds could generate meaningful alpha—at least not in comparison with other classes of funds. But that mindset has changed. According to BCG research, institutional investors increasingly recognize that impact investing is not simply a philanthropic vehicle, but one that can produce attractive returns. A major catalyst for that shift has been climate change.

With up to 20% of gross domestic product globally at risk from carbon emissions, the E in ESG has gone from an abstract notion to a concrete business challenge—with specific solutions that financiers can fund. In the past couple of years, commercial private equity firms have entered the green space at scale, with ten times as many funds launching in 2018 as in 2000. In addition, numerous boutique firms have sprouted up, focusing exclusively on clean tech, alternative energy, and climate change. This funding-fueled innovation has delivered impressive returns, with the first generation of clean energy and clean-tech superstars already rivaling Big Tech leaders in total shareholder returns.

Having seen the value of financing positive environmental change, investors should approach the S of ESG with similar resolve—but with much greater speed. Neither they nor society can afford to follow the same decade-long learning curve as in the past.

Social Investing Should Be the Next Impact Frontier

The need to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the workplace has taken on greater urgency. Although private-sector pledges to support marginalized communities gained momentum in the US in 2020 after the death of George Floyd and the racial reckoning that followed, women and communities of color continue to face obstacles worldwide in their efforts to acquire development investment, business financing, and employment.

COVID-19 has been an exacerbating factor. Globally, 64 million women left or lost their jobs in 2020 as a result of the pandemic, departures that collectively extracted roughly $800 billion in income from the economy. Additional hurdles confront people of color. In the US, for example, Hispanics and Blacks represent less than one-third of the female labor force, but they accounted for about 46% of job losses among women over the past two years. Racial disparities in health outcomes and health access persist among men and women of color, and the pandemic has made those inequalities more acute. Essential workers, whose jobs put them at higher risk of COVID-19 infection, are disproportionately people of color.

Concrete areas for developing solutions have emerged. They include greater access to childcare, more flexible workplace arrangements, improved skills training, and more effective on-ramping. Innovations that allow underrepresented groups to contribute their talent and participate in the labor force could inject trillions of dollars into the global economy by 2050. But these solutions require significant investment, and the level of financing today is nowhere near where it needs to be.

Although philanthropic and development finance institutions contribute upward of $150 billion globally in support of ESG initiatives, this figure falls far short of the roughly $3 trillion required to meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Corporation for Enterprise Development calculates that without changes to existing policies to improve capital access and opportunities for people of color in the US, it would take up to 228 years for Black families and 84 years for Latino families to accumulate the same level of wealth as white families. And the World Economic Forum estimates that without greater investment in gender equity, it will take more than 267 years to close the economic participation and opportunity gap between men and women globally.

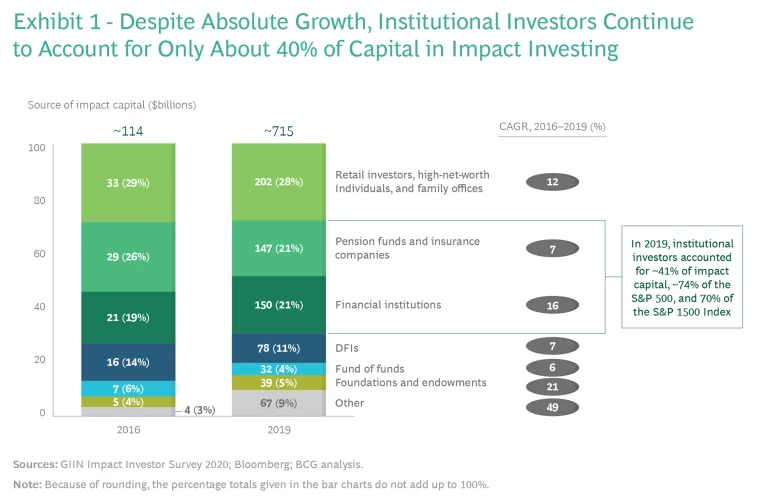

Only institutional investors have the capital resources to effect change at the scale needed. To date, however, their contributions represent a relatively small share of the total impact investing pool—funding that is intended to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. (See Exhibit 1.) And in interviews conducted with a global cadre of institutional investors, we found that many continue to rely more on shareholder activism and saber rattling in the boardroom and less on deploying their capital to force improvements in DEI.

Viewing Small Funds Through a Big-Fund Lens Leads to Diminishing Returns

One key reason for the relatively low level of institutional investor funding is that many pension funds, insurers, and sovereign wealth funds apply the same conventions about ticket size and track record to social impact funding as they do to their large-scale portfolio investments. But social impact is a very different space. Deal sizes are necessarily smaller, the data on outcomes is less mature, and accurately gauging the benefits of addressing factors such as financial inclusion, poverty alleviation, and affordable housing may require examining second- and third-order effects that can also financially benefit the invested companies. By attempting to conform small-fund dynamics to big-fund hurdles, institutional investors deny communities and themselves the impact and yields they might otherwise generate.

That’s a huge missed opportunity. Attracting more institutional capital could allow social impact funds to significantly extend their reach and increase economic inclusion. In return, pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds could gain access to high-quality investment opportunities in growth markets, enabled by the differentiated deal access and expertise that equity-focused impact fund managers can provide. BCG’s research has found a strong correlation between gender and racial equity and business performance, with leaders seeing higher rates of revenue growth, stronger innovation, and greater employee and customer satisfaction.

Three Ways Institutional Investors Can Make Social Impact a Win-Win

By focusing on three core steps, pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds can transform the scale and reach of their social impact while maintaining their fiduciary responsibilities:

- Cast aside preconceptions about investment returns. Most investors have at some point viewed impact investing as concessionary, and many still round down the potential value in their heads even when they are screening market-rate impact funds that are designed to achieve returns similar to those of commercial, non-impact investments. Impact managers can help overcome these tendencies by encouraging clients to examine the actual investment thesis. For example, clients may be pleasantly surprised to learn that the impact fund they are considering has an underlying focus on fintechs, edtech, or some other high-growth market. As one limited partner stressed, “We need to show clients how impact investing increases their returns as opposed to detracting from them.” The TPG Rise Fund, for example, invests in triple-bottom-line companies that offer high growth potential, financial viability, and measurable progress toward the UN’s SDGs, giving managers a clear basis to demonstrate value to clients.

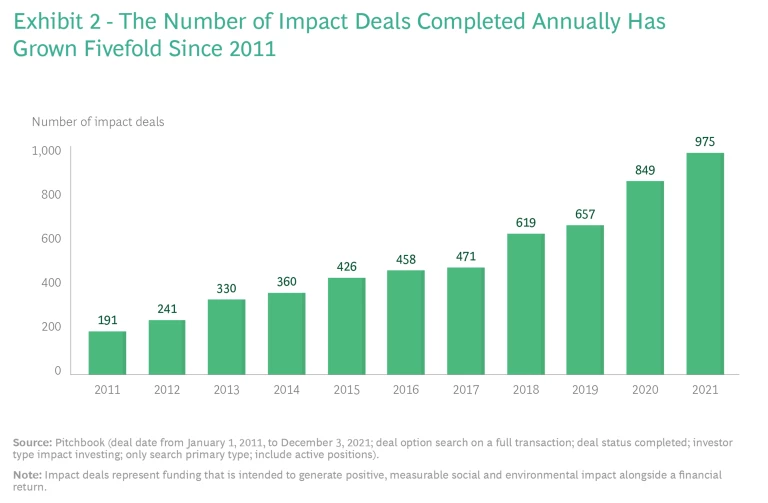

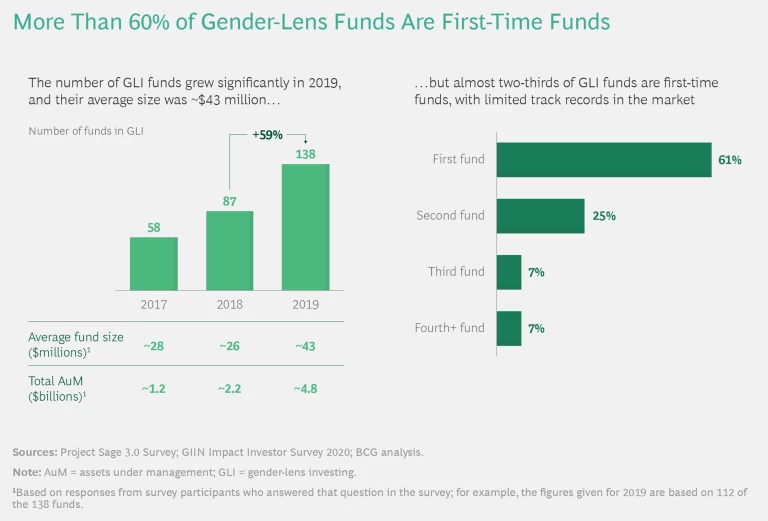

- Reevaluate investment criteria. Social impact funds have proliferated in recent years, with 36 new impact investors added to Pitchbook and close to 1,000 impact deals reported in 2021. (See Exhibit 2.) Because many impact leaders are first-time managers launching first-time funds, applying traditional track-record criteria doesn’t work. Instead, institutions should flex their approach. Examining the résumés and experience sets of fund founders and team members can be a useful proxy for track records. Institutional investors should reevaluate their ticket-size minimums, too. Many maintain a minimum ticket size of $10 million to $30 million—a threshold that precludes nearly all social impact investing, since the mean gender-lens investing fund hovers at around $40 million. (See “Even the Largest Gender-Lens Investors Don’t Fit Institutional Criteria.”)

Even the Largest Gender-Lens Investors Don’t Fit Institutional Criteria

WWB’s two funds have combined assets under management of roughly $125 million, making them among the largest players in the GLI space. But that size falls well below the average funding threshold for institutional investors, denying them access to the biggest pools of capital. Most gender-lens fund managers find themselves in the same bind as WWB. Although GLI has grown in recent years, with the total number of funds more than doubling between 2017 and 2019—from 58 to 138—most of these funds are small and less than one year old, which limits their ability to attract institutional investor capital. (See the exhibit.)

Increasing access to institutional funding can deliver big dividends. For example, one company that WWB’s funds invested in was Ujjivan, an Indian microfinance institution. By identifying gaps in the bank’s product offerings and customer service practices, WWB helped Ujjivan increase the number of women clients it served by 80% and drove major improvements in the institution’s gross and net income. The company’s subsequent initial public offering became the most oversubscribed in India’s history, by a factor of 40.

- Develop programs for emerging impact managers. Managing any fund is a time-intensive exercise. As one investor we spoke with noted, “It takes about the same amount of effort to conduct due diligence on a $10 million investment as it does on a $100 million investment.” To make investing in new fund categories more financially viable, some large institutional investors have established an “emerging fund manager platform,” engaging an external advisor to handle the administrative work. To date, most such platforms have focused on private equity and real estate niches. Extending their use to social impact funds could allow institutional investors to make smaller bets and provide a path for impact funds to establish track records and increase their scale over time.

The need for social impact investing has never been greater, and as the triple-bottom-line benefits from engaging in this space become clearer, institutional investors have the opportunity and the imperative to step up their funding and catalyze growth. Those that seize this opportunity have the chance to take the lead in a space likely to become the next frontier in generating alpha.