Our survey shows that leaders have an opportunity to solve the industry's labor challenges by accommodating changing worker priorities.

The US hotel industry continues to be affected by the aftershocks of COVID-19. During the pandemic, far more hotel workers than employees in any other industry were laid off or had their working time reduced. When the conditions for travel and tourism improved, most guests returned—but many employees have chosen not to.

The resulting hotel labor shortage means that employers must pay a premium for workers. But that’s not the only consequence. To counter rising hotel industry labor costs, many companies are cutting back elsewhere, reducing concierge and shuttle services, food and beverage offerings, and the myriad other benefits that guests used to take for granted. This, in turn, erodes the guest and employee experience. The combination of higher costs and lower revenues can put a severe squeeze on hotel profits.

What will it take in a post-pandemic world to change this state of affairs and enable the US hotel industry to attract new employees, retain current ones, and win back former staff? To answer this question, BCG, New York University’s Jonathan M. Tisch Center of Hospitality, and the American Hotel and Lodging Association earlier this year consulted industry leaders to identify the root causes of the current labor challenges and suggest solutions. We then surveyed 1,200 current, former, and prospective hotel industry employees, and employees of adjacent industries such as restaurant and retail, to test the leaders’ ideas on how the industry can better attract and retain workers.

The survey aimed to offer hotel industry leaders new insights by asking broad questions (such as about job priorities and respondents’ reasons for choosing to work in the industry) and seeking respondents’ reactions to specific ideas that participants in the earlier consultation had suggested. We divided our survey sample into four cohorts so that we could test targeted options. (See “Our Survey Methodology.”) We found that the hotel industry has an opportunity to solve its labor challenges by improving its flexibility, creating more varied entry routes for new workers, and developing clearer pathways to career advancement. Here are some of our main findings in more detail.

Our Survey Methodology

We also asked respondents to indicate the extent of their interest in a set of actions related to each of the top four factors they identified as most important when considering a job in the industry. Specifically, we asked them to select their level of agreement with a series of actions or statements about the hotel industry on a five-point scale (ranging from “strongly agree” or “definitely” to “strongly disagree” or “definitely not”).

The survey sample consisted of 1,197 respondents, composed of 266 current hotel employees, 271 former hotel workers, 75 potential hotel industry entrants between the ages of 18 and 24, and 585 current employees in adjacent industries. We conducted the survey from April 18 to April 25, 2022.

Transparent Compensation Pathways Are Especially Popular

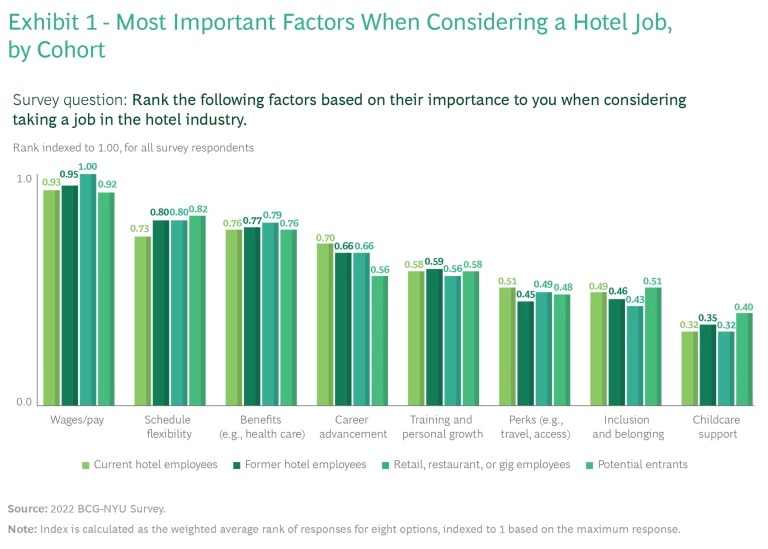

When we asked survey respondents to rank the factors that were most important to them when considering a job in the US hotel industry, financial compensation unsurprisingly came first across all of the cohorts we surveyed. (See Exhibit 1.) Nevertheless, our survey indicated that respondents weren’t exclusively concerned with higher pay.

We presented respondents who ranked “wages and pay” as a top four factor for considering a job in the hotel industry with six options that the industry might take to improve its handling of remuneration. Of these, transparent pathways to pay raises and bonuses was especially popular, with a net 90% of respondents in favor, making it one of the most positively rated options across the entire survey.

A net 88% of respondents approved of continuous benchmarking to ensure that remuneration in the hotel industry was equal to or above that for comparable jobs in similar industries. And a net 86% supported actions that ensured that remuneration was sufficient for employees to depend for their living on a single job rather than having to work multiple jobs.

All Cohorts Highly Value Schedule Flexibility

Our survey respondents identified schedule flexibility as the next-most important consideration after remuneration (out of eight possible factors listed) for a job in the industry. For several years, hotel companies have promoted practices that enhance flexibility, increase employee mobility, and ensure that properties have sufficient staff to deal with issues such as fluctuations in seasonal demand.

However, practices such as “nomadic” flexibility—which allows staff to work for several months at one location and then rotate to another—and scheduling that gives employees the option of working noncontiguous shifts within the same day received only slightly better than neutral ratings from survey respondents who ranked schedule flexibility as a top-four factor in gauging the desirability of a job in the hotel industry. In contrast, both the ability to decide which days and what time of the day to work and the ability to determine how many hours to work each week received net positive support of around 90%.

Our findings suggest that the industry must change how it recruits and manages employees if it is to accommodate their priorities. For example, instead of just recruiting for a cashier or front desk associate, employers could also specify that they want to hire for specific days of the week or times of the day. To facilitate these changes, technology that makes it easier to swap shifts, redeploy workers, and ensure appropriate skills coverage across a hotel property—easing the burden on managers—will be essential.

Finally, flexibility was about twice as important as childcare support to current employees and potential entrants. Although childcare was more important to young people still making career choices than to any other cohort, the desire for flexibility extends far beyond caregivers.

Inclusion and Belonging Actions Could Boost Retention

An important theme of our discussions with industry leaders centered on how the industry must act to improve racial, ethnic, and gender diversity and foster a greater sense of inclusion and belonging if it is to attract and retain staff. This reflects ongoing industry conversations about prioritizing efforts to recruit a diverse workforce and foster a working environment that helps individuals from all backgrounds to succeed.

Significantly, respondents rated the factor “inclusion and belonging” as less important than we had expected. But even though this factor didn’t rank among the top factors across all cohorts, it was still meaningful. In addition, inclusion and belonging were more important to potential entrants and current hotel employees (over 30% of whom ranked it among their top four factors) than to former employees, suggesting that industry action in these areas could help employers to retain staff.

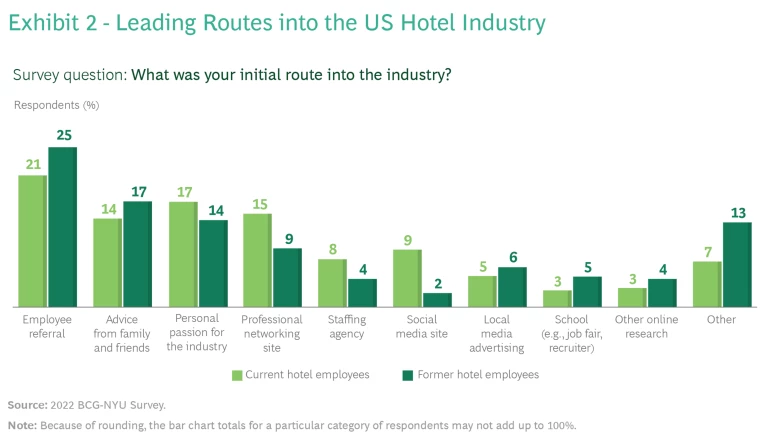

Another way to get a handle on the true importance of inclusion and belonging in the hotel industry is to look at how current and former hotel employees gained entrance to it. (See Exhibit 2.) Our survey found that the leading route into the industry was through employee referral. Creating a diverse and inclusive workforce will enable a more diverse set of potential employees to join by using their networks and connections, thereby strengthening the industry over time.

At the same time, far fewer current and former hotel employees in our survey said their pathway into the industry started at school than we had expected. This suggests schools could create greater awareness of the benefits of hotel work among their students. But this would require the hotel industry to engage more proactively with school leaders, career guidance counselors, and career services officers.

Different Cohorts Have Different Key Concerns

To better understand perceptions of the industry and to gauge the degree of concerted action needed to attract potential entrants, retain existing staff, and persuade former employees to rejoin, we looked at four different cohorts: current hotel employees between the ages of 18 and 55, former hotel employees from 18 to 55, current employees of adjacent industries (including retail and restaurants) from 18 to 55, and young adults from 18 to 24 years old who were considering a career in the hotel industry.

Current Industry Employees

Growing the US hotel industry’s labor force starts with retaining those who already work in the industry. Fortunately, current employees are more positive about the industry than any other cohort. They believe more strongly that employees are valued; they have a stronger sense of belonging; and they are more likely to feel that employment in the industry is accessible, provides valuable skills development, and offers good opportunities to build a successful career. Indeed, most current employees cited career advancement opportunities as their main reason for continuing to work in the industry. (See Exhibit 3.)

Despite this, our survey showed that the industry has work to do to become an employer of choice and to create effective, transparent career pathways. A large majority of current employees who indicated that career advancement was a top four factor for a job in the hotel industry endorsed two options in this regard: a fast-track pathway to promotion to manager level within two to three years of entry to the industry (with a net 85% in favor); and the potential to receive promotion to general manager or to work in a corporate-level position within three to four years of promotion to manager (with a net 81% in favor).

Respondents also strongly favored greater availability of coaching, career path guidance, resources, and training to help them achieve their goals. Employer-provided training in skills needed for career advancement within the industry and rapid onboarding training for new roles each received 90% net approval. Employers can start to tackle these areas by creating mentorship programs and publicizing success stories that highlight the different career paths employees have taken within the industry.

Former Industry Employees

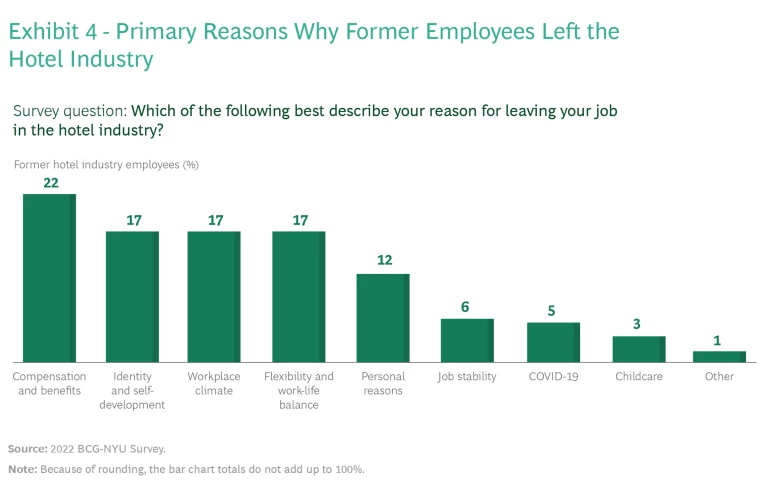

To create effective strategies to win back employees who have left the industry, leaders must answer two questions: why did they leave, and where did they go? In our survey, 22% of former employees identified compensation and benefits as their primary reasons for quitting the hotel industry. The survey sample included respondents who had left the industry across a range of previous years: 35% had left within the past two years (one-third of them by furlough and two-thirds by choice); 25% had left between two and five years ago; and 40% had left more than five years ago. After compensation and benefits, the next three most frequent reasons given for their departure—identity and self-development, workplace climate, and flexibility and work-life balance—all tied at 17%. (See Exhibit 4.)

Employee destinations after departing the hotel industry are revealing. Some 25% of former hotel workers took jobs in other hospitality areas, including the food, gambling, and leisure cruise sectors; and 14% left to work in retail and related customer-facing roles. But another 14% moved into health care, childcare, or care for the elderly. This suggests that the lines between hospitality and caregiving are blurring as the desire to deliver distinctive, customer-oriented service becomes a point of competitive differentiation for companies in both sectors. If our hypothesis is correct, this emerging trend will exacerbate the demand pull on hotel industry talent from competing employers.

Some 35% of former hotel industry employees considered their new job to be part of the gig economy. This is in line with research that we conducted in 2021. Former employees in this category weren’t limited to individuals who worked for conventional gig economy employers such as rideshare companies. They also included individuals who worked in retail, food, health care, or transportation but self-identified as gig workers because they had more flexible schedules and working arrangements. The lesson: the hotel industry must take steps to avoid falling behind competing industries that can attract talent because they offer the option of a self-directed schedule.

These findings point the way to solutions for winning back workers. According to 29% of respondents, increased pay and compensation would persuade them to return to a job in the hotel industry, making it the biggest lever available to employers. However, the hotel industry faces significant structural challenges in addressing wage imbalances with other industries. For example, hotel employees receive lower average hourly earnings than retail workers, and they work fewer hours per week. Fortunately, in the absence of higher pay, employers can use other levers to retain staff. According to our survey, clearer career advancement pathways would convince 21% of former industry employees to rejoin, and greater scheduling flexibility would be decisive for 17%.

Potential Industry Entrants

We surveyed a specific cohort of younger individuals (from 18 to 24) who were at the beginning of their careers and might join the hotel industry. They were not currently employed in the hotel industry, and had reached an education level below a bachelor’s degree. Industry employers must seize the opportunity to attract such potential entrants—through compelling messaging, targeted outreach programs, and appealing job characteristics—or risk losing them to competing industries.

Like our other groups, potential entrants listed remuneration as their leading reason for considering accepting a job in the hotel industry. However, they viewed it as less important than other cohorts did, ranking it ahead of other factors by a smaller margin. Consequently, employers are unlikely to attract these prospective employees simply by offering higher wages. Instead, they must address other priorities, including flexibility, inclusion and belonging, and training.

We found that career advancement opportunities were far less important for potential entrants than for other cohorts, and especially for older workers. Instead, the cohort cared more than any other group about schedule flexibility. This was unexpected, as we had anticipated that older workers with childcare or family care responsibilities would value flexibility most highly. In fact, 18- to 24-year-old potential entrants rated having a flexible schedule as the second-most important consideration for a job in the hotel industry, after wages, by a large margin over the third-most important consideration.

Another factor—inclusion and belonging—was also more important to this cohort than to others. To attract these younger potential entrants, the industry must become more aware of, and responsive to, broader societal efforts to improve inclusion and belonging. In general, individuals in this cohort also advocated strongly for employer-provided training in skills that can help them perform their job well and are transferrable.

Although the perks that the hotel industry can provide did not rank among the strongest indicators that a potential entrant would be likely to take a job in the hotel industry, they were still important to this cohort. Such perks include free or discounted accommodation, tickets to events and attractions, and discounts on products such as bed linen and kitchenware. These give industry employers opportunities to increase new entrants’ compensation packages, without offering extra cash, in ways that companies in other sectors cannot easily match.

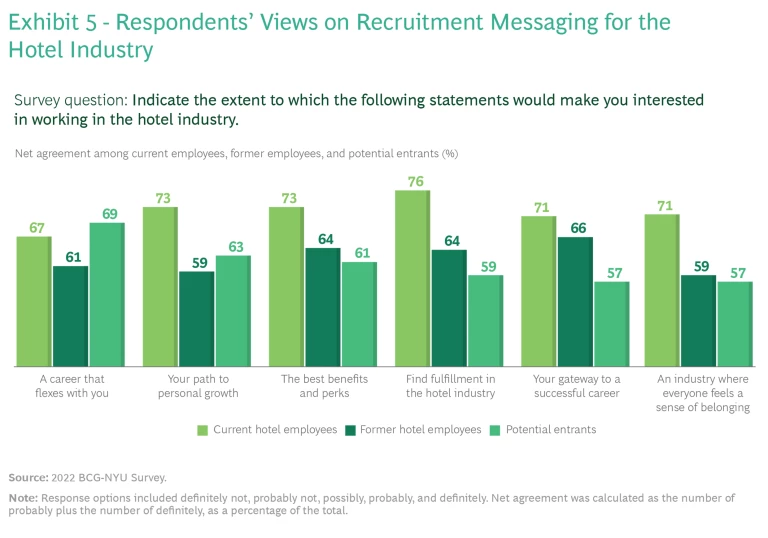

We also tested a range of possible messages about the hotel industry to understand which were most likely to persuade potential entrants in this age group to work in the industry. (See Exhibit 5.)

We found that the most popular messaging emphasized career flexibility and the ability to work when you want and how much you want. The next-most-popular messaging highlighted the opportunities the industry offers for personal growth and on-the-job learning. The industry can build such targeted messages into outreach programs and recruitment campaigns aimed at attracting this important contingent of potential employees.

Our findings suggest that the US hotel industry can become a far more attractive employer by taking action in certain well-defined areas. Some of these measures, such as greater flexibility, are likely to resonate across a wide range of individuals, from current employees to potential industry entrants. Others will have a more targeted appeal. Consequently, hotel companies should think carefully about which actions will work best for specific employee groups. And although individual employers could unilaterally adopt some measures, others—such as the introduction of new technologies, outreach programs, and transformative marketing initiatives—will require cooperation across many organizations . By taking these steps today, the industry can build the diverse, committed, and high-quality workforce that it will need to flourish in the future.

The authors thank Rosanna Maietta of the American Hotel and Lodging Association for her contribution to this report. They also thank Dynata, the world’s largest first-party data and insights platform, for its support in developing and fielding their online survey.