Activism is back with a twist. Increasingly, the attackers come from within—longstanding investors impatient for better returns. Management needs a new playbook.

Shareholder activism is returning to prepandemic levels, but with a twist. Professional activists like Elliott or Starboard are not driving the resurgence. Instead, a new generation—largely comprising traditional investors—is leading the charge. They have often held their positions for a while, are impatient for better returns, and are increasingly comfortable pushing for change.

These “activists within” may be right, they may be wrong, but ignore them at your peril. Attacks led by these less experienced, occasional activists have a much worse value creation track record than those led by professional activists.

With activism risk now coming from all directions, management’s best defense is to be prepared. Business leaders need to understand and address the issues that could be at the heart of a potential attack; they need to treat investors like customers, engaging them proactively and constructively; and they need to develop a clear playbook for risk reduction and shareholder activism response .

The Shifting Activism Landscape

Activism grew rapidly following the Great Recession, reaching a peak in the five years prior to the pandemic. From 2015 to 2019, activist campaigns averaged 179 per year—almost double the average for the preceding half decade. After a slowdown during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, activism bounced back in 2021 with a total of 180 campaigns. Through November 2022, activists have initiated approximately 145 public campaigns with about 160 projected for the full year.

But these numbers don’t tell the full story. First, they underestimate the level of activity. Activists increasingly operate under the radar, approaching companies privately with their demands. We estimate that in 2022 only about a quarter of activists made a public statement versus about half a decade prior.

Second, these numbers mask the rise of the new generation of activists. Nonprofessional activists—defined as entities that have conducted two or fewer campaigns since 2000—now lead the majority of campaigns. In 2012, they accounted for approximately a quarter of attacks; by 2021, the percentage had exceeded 50%, and in 2022 it stands at nearly 60%. (See Exhibit 1.)

And third, despite their poor value creation record, activists have become more successful at achieving their campaign objectives, such as gaining board seats. The average annual number of board seats won by activists, now about 120, has nearly doubled over the last decade.

We see two factors sustaining or even accelerating the growth of activism going forward. First, the increasing concentration of share ownership by large institutions means an activist has a smaller number of entities to convince. According to the US Federal Reserve, between 1963 and 2011 the share of equities owned by individual investors declined from 84% to 40% in the United States—and this trend was mirrored in other nations. In the United Kingdom, for example, the share of equity ownership by individuals declined from 50% to 11% between 1963 and 2012.

And second, in the United States, the SEC’s new universal proxy rules could be a game-changer for activists. These rules require that all shareholders receive a single proxy ballot—paid for by the corporation—that includes all board candidates and proposals, whether proposed by management or activists. This significantly decreases campaign cost and complexity for activists and enables shareholders to vote “a la carte.”

Understanding the Activists Within

Given that campaigns are now likely easier and cheaper to run, it is not surprising that new players have entered the activism game. And traditional investors have been leading the way. Since 2015, 70% of nonprofessional activist campaigns were led by a traditional institutional investor—a hedge fund, investment advisor, a mutual fund complex, a public pension fund, or another financial institution .

Historically, frustrated investors had only two options: hold their position and hope or sell it and take a loss. Increasingly, they are seeing activism as an attractive alternative. Unfortunately, they may be their own worst enemy. As a class, these nonprofessional activist investors destroy more value than those with more experience.

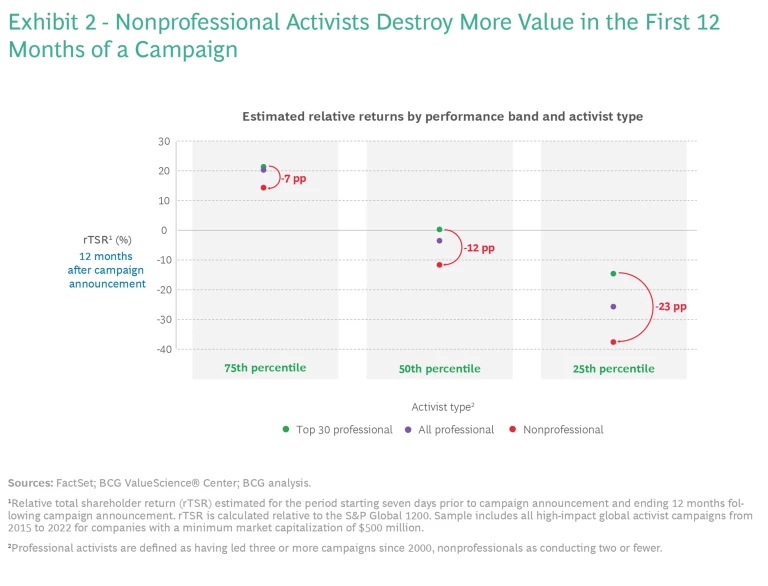

We compared the performance of campaigns led by nonprofessionals with those led by professionals. Twelve months following the campaign announcement, the median campaign led by a nonprofessional delivered a relative total shareholder return (TSR)—that is, the target’s TSR relative to that of the market as a whole—12 percentage points lower than that of the median campaign led by one of the top 30 activist firms. The performance deficit is narrower (about 7 percentage points) for the campaigns at the 75th percentile, and wider (about 23 percentage points) when we move down to the 25th percentile. (See Exhibit 2.)

This performance differential could be because nonprofessionals, compared with experienced activists, target companies with market values 40% smaller. Or it could be a learning effect—it may just take more than a couple of campaigns to get good at activism. And we see from Exhibit 2 that the performance of “professional” activists (defined as an entity that has led three or more campaigns since 2000) falls between that of the top 30 and the nonprofessionals. Or perhaps generalist institutional investors are unable to attract the same level of talent as more focused and experienced activist firms.

An Ounce of Prevention

At the heart of any activist attack is an investor problem.

If a company has unhappy investors, its management and board are in a weaker position if a traditional activist comes to call. And investor discontent is the key motivator for most nonprofessional activists. So, the best way to inoculate against activist attacks from professionals and nonprofessionals alike is to convince investors management offers the best path to value creation.

To build immunity to—and in the worst case, minimize the impact of—an attack, we recommend that management focus in three areas: adopting an activist mindset; engaging investors in constructive dialogue; and developing a clear playbook for activism response.

Adopting an activist mindset. Take a dispassionate look at your organization and its performance. What vulnerabilities do you see that could become the thesis of an activist attack? A periodic strategic and operating review that pressure tests the business is essential. The goal is to understand where you are underperforming peers or your potential—and what you are going to do about it.

Is your strategy and value creation story convincing—and what plans do you have to address critical uncertainties? Any investor will want your stock to be fully valued today or on the right path to being fully valued soon. If you can give them a clear strategic plan they can trust, but verify, they’re much less likely to make demands themselves. Leading activists and value investors tend to keep in close touch. Thus, if a critical mass of investors supports management’s plans, professional activists will likely see less opportunity to drive change.

Are your governance structures effective? Board seats are a key activist demand because of the leverage they offer. Investors are unlikely to push for board changes if they trust that your board has the inclination, stature, and capabilities to fulfill its oversight role. And investors can quickly tell which directors are truly engaged in shaping the organization’s success. Are there opportunities to proactively reshape your board by filling in missing expertise, easing out directors who might be seen as too close to management, and increasing board diversity?

And finally, how are you positioned vis-à-vis the most common activist themes around margin and return gaps, cost structure, and ESG?

Engaging investors in constructive dialogue. Getting value investors to understand and buy into your strategy requires real dialogue. And a recurring theme from our investor interviews is that management and boards fall short in their ability to probe, listen to, and credibly respond to investor concerns.

But before reaching out, understand who your most important passive, active, and individual investors are. Focus not only on your largest investors, but also on influential investors with smaller stakes. Are they buying, holding, or selling? What returns, realized or unrealized, have they seen? How have they voted their shares in the past? What, if any, concerns have they raised in the past? Have any engaged in another company’s activist saga?

Invest time in being able to express your strategy succinctly: how you will be both a great company and a great stock. What position does your company want to occupy in the future and why? Does it have a right to win in that space? What investment (and disinvestment) is required? How, and over what time period, will you create peer-beating value for investors? To what degree are you trading off short-term results for medium-term value? What are the key milestones along the journey that confirm your key strategic assumptions and demonstrate progress toward the vision? What key uncertainties do you face? And given those uncertainties, for what future competitive environment scenarios are you ready?

Once prepared, start engaging. Whether investors come to you, or you visit them as part of a roadshow, make sure you are meeting with the one or two most important decision makers. Presenting to a room with a dozen people at a large fund complex might be a necessary part of the process, but also make an effort to create a dialogue with individual fund managers who often make their own investment decisions. There should be no disclosure issues if you have already discussed your strategy publicly.

Lay out your value creation strategy, being clear that you understand the weak spots and key uncertainties and have a plan to address them. Be clear about which strategic variables management can control and which are driven by the macro environment. It is essential for CEOs to be realists to earn credibility with investors. Then probe. What are their concerns? Where possible, try to address them with a fact-based argument that supports your strategy. Where not, follow up.

Developing a playbook for activist response. Despite best efforts, there is always a chance that an activist will knock on your door. So, it is important to have a “break glass in case of emergency” plan ready for a thoughtful and coordinated response. Which advisors will you retain to support your defense and how will you organize internally? Knowing the first saves precious time, and knowing the second saves precious executive attention, ensuring that some leaders remain focused on driving the business and freeing others to turn their attention to the activist. Any plan should include clarity on how best to engage the board, including providing board members with critical data and answers to likely questions. We also recommend going through a war-gaming style “dry run” of the initial response to an attack.

At the end of the day, the best way to avoid an “activist within” attack is to address frustrations and misperceptions before they come to a boil. In our experience, most disagreements are at the root about timeframes and tradeoffs: How much are investors willing to sacrifice current returns for potentially superior future ones?

Activism preparedness—this process of self-examination and investor dialogue—should become an ongoing aspect of your investor relations efforts. Doing it well may require upgrading your investor relations to be more than a reactive public relations function. Some of the best investor relations teams are led by former investors or analysts who can help management articulate strategies that better resonate with investors.

In all cases, the time spent preparing will build your immunity to an activist attack. And if attacked, this exercise will increase the odds that you will either prevail or be prepared to make a rapid settlement on better terms that will lead to better value outcomes for all shareholders.