To meet people’s needs and make their health systems as efficient as possible, governments need a coordinated approach to care.

Often the best health care a country can provide happens before and after a person actually sees a doctor. Preventive care, counseling, and even logistical support, such as a ride to a follow-up appointment or to a pharmacy to pick up a prescription, can have a huge effect on health outcomes. Yet such services are all too rare. In many countries, government efforts to ensure a healthy population are split in two: medical care (the treatment of disease and injuries) and social services (preventive care in support of vulnerable citizens and counseling for ongoing issues such as addiction). This is a fragmented and unsustainable approach that increases the cost of care and leads to poor outcomes. Instead, governments need to link excellent medical care with proactive, comprehensive social services.

The challenge is growing. Chronic lifestyle problems such as obesity, heart disease, and diabetes are becoming more prevalent, requiring ongoing, integrated care to address root causes, and they are stressing health systems around the world. Countries also face fiscal pressure to reduce health care spending, even as they must provide for larger and often older populations. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for prevention, education, and other measures that have a large impact on health but lie outside of traditional care settings.

Payers and providers have a role to play in integrating health care and social care, but governments bear the biggest responsibility. Some countries have already taken steps in this direction, and others can learn from their experience. It’s a smarter approach that leads to more efficient care, reduces the need for invasive and costly procedures, and—most important—fosters healthier populations.

Social-Service Interventions Lead to Better Health Outcomes

To understand what can go wrong when medical care and social services aren't linked, consider a hypothetical situation. A patient arrives in the emergency room complaining of shortness of breath and is diagnosed with hypertension. Her doctors prescribe medication and recommend some changes in diet, along with an exercise plan. The patient gets the prescription filled but does not consistently take her medication. Her income is low and she struggles with depression, making it tough for her to take steps to improve her condition. She misses one follow-up appointment, then another. Six months later, her blood pressure has dramatically worsened, and she winds up in the emergency room again, now requiring more comprehensive and expensive care and a hospital stay.

Social services are a strong determinant of good health outcomes because many health issues have underlying social causes. For that reason, social-care workers are ideally positioned to improve medical care. They can help identify vulnerable peoples’ needs early on, help them stay well longer, and reduce the likelihood that they will need health care services.

Yet in many countries, social care is underfunded and notoriously difficult to fully integrate into traditional health care systems . People often need support for a range of problems—from mobility challenges to mental health issues to learning disabilities to addiction—which require different types of support that can be hard to coordinate. Insufficient governance means that stakeholder roles and accountability are unclear. Patient eligibility rules can be opaque because of rigid categorization schemes. Most social-care networks lack enablers such as data and technology , which would help them make the case for a more direct role in supporting medical care.

Payers and providers have a role to play in integrating health care and social care, but governments bear the biggest responsibility.

Despite these challenges, governments and other stakeholders that integrate social services and traditional health care are getting results. In addition to improving people's health outcomes and quality of life, integrated health and social services give governments an opportunity to target services more effectively and thus spend more efficiently at a time when health and social-care budgets continue to balloon. One estimate found that England’s national health service could save more than $6 billion if all citizens 65 and older had free social care.

Five Key Steps to Integrated Care

There is no universally applicable way to integrate health care and social services. The right solution will vary by country and region. Still, from our research and client experience, we have identified five steps to establishing a basic framework that virtually all governments can apply and potentially adapt to meet their needs. (See Exhibit 1.)

Establish national policies and programs for integrated care. First, governments need to set national policies establishing an explicit link between social services and health outcomes. Our analysis indicates that systems with a high level of integration succeed because they are aligned on policy, which enables coordination, governance, capacity planning, funding, and data sharing. When designing solutions and programs, policymakers in these systems use a population-centric lens, considering the interdependencies among different domains—for example, education and drug dependency—rather than crafting isolated solutions for each one. This approach requires agility and multidisciplinary teams that can consider all facets of a specific health issue.

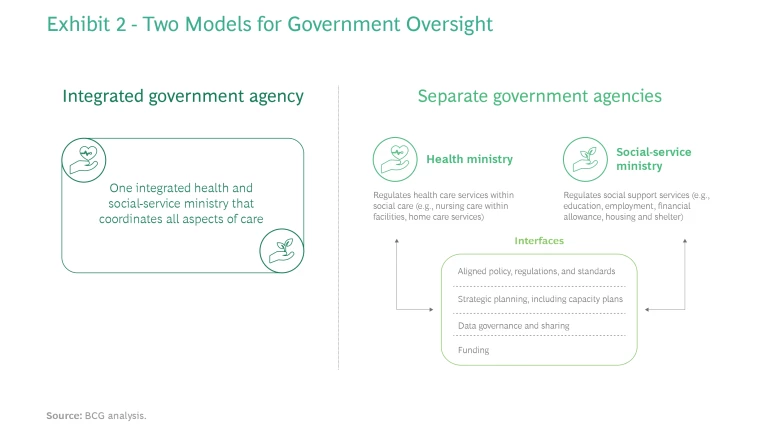

Approaches to integration vary by country. France, Sweden, and England have a single integrated health and social-care ministry, with distinct administrative departments. Other countries, such as Australia and the Netherlands, have separate health and social-service ministries. (See Exhibit 2.)

Additionally, health systems must rethink health sector governance and regulation , with the goal being to set clear objectives, generate robust policies and regulations, define stakeholder roles, and monitor system performance.

Understand the population’s overall health and social-care needs. Second, governments need to understand and prioritize their citizens’ most pressing health and social-service needs so they can deploy resources effectively. It’s essential to use a needs-based approach in order to identify the population segments that will benefit the most from targeted care. This approach considers populations holistically, assessing people's overall physical, mental, and emotional well-being. The needs-based approach is different from the traditional, medical-based approach used by some governments and providers, which establishes rigid categories but oversimplifies patient needs and potentially overlooks the needs of those whose conditions can't be neatly categorized.

For example, the medical-based view categorizes a person’s disability along a spectrum from least to most severe, looking solely at its physical impact, such as on mobility. The needs-based approach puts more weight on the impact that the disability has on the person’s daily life, which may include—in addition to mobility—the ability to attend school, work, and develop relationships. This more complex way of understanding health and social-care needs ensures that services are more targeted—and ultimately more effective.

Integrate health and social-care pathways at the operational level. In addition to integrating health and social care at the strategic level, governments need to establish the same level of integration at the operational level. In countries such as England, France, the Netherlands, and Sweden, a case manager (typically, a nurse or social worker) performs an initial assessment of a person’s eligibility to receive social care and then acts as the point of contact for coordinating all health and social services from different providers. Another approach is to structure health and social care though a single entity or provider that offers people one-stop access—and often a more seamless and intuitive experience.

By making it easier for vulnerable people to navigate the array of services they need, both approaches offer a range of benefits, including:

- Improved patient outcomes

- More cost-effective care owing to the targeted use of the right resources at the right time, which reduces avoidable hospital admissions

- Higher satisfaction for recipients, who spend less time and effort finding, navigating, and accessing services

To achieve this level of operational integration, social-care workers must be empowered and have a clear mandate within the ecosystem. Governments should devise programs to support volunteers and family members as caregivers. (See “The Formal and Informal Care Workforce.”) In addition, social-service networks should include not only formal medical providers but also private-sector and nonprofit entities, which may be able to offer specialized services to certain individuals. In Scotland, for example, nonprofits operate residential care centers and work closely with community authorities to coordinate social and health care. The broadest possible array of providers means more choice for users, which unleashes competition to potentially increase quality and reduce costs.

The Formal and Informal Care Workforce

Keep learning to improve quality. Systems that integrate health care and social services need to evaluate the quality of the outcomes they deliver on a continuing basis. One way to do this is to apply value-based health care principles.

In essence, value-based health care refers to the outcomes achieved by an individual or a population in the context of the expenditure required to deliver those outcomes. Measuring outcomes ensures awareness and transparency regarding performance and creates opportunities to identify best practices, share lessons learned, and drive a culture of process improvement centered on what matters most to patients. Health systems that do this gain confidence that their services are providing patient-centered outcomes in the most cost-effective way. Governments, too, should continually assess and improve their coordination with payers and providers. (See “How Payers and Providers Can Support the Shift to Integrated Care.”)

How Payers and Providers Can Support the Shift to Integrated Care

All providers—public, private, and nonprofit—need to transform their services to better integrate social care. For example, a major provider in the US had struggled to meet the needs of people with limited access to primary health care. That population segment experienced more complex health issues and worse outcomes because of the delay in getting medical assistance. But relatively straightforward interventions significantly improved these patients' health outcomes. The provider started offering transportation to medical appointments. It also provided community rooms for older people to offset isolation, more accessible pharmacies, and even behavioral health specialists to help monitor the health and quality of life of patients.

Similarly, payers need to incorporate social services within their coverage policies as a complement to health care. They are in the best position to incentivize the transformation system-wide while reducing the overall cost per individual.

Invest in key enablers. Finally, to create an efficient integrated health and social-care system, governments need to invest in critical enablers such as funding, education, and technology.

Securing adequate funding and resources is a well-known challenge for social care, leading to variations and gaps in coverage and eligibility. For example, the US has an income-tested system that provides social-care services to low-income groups, but the rest of the population must pay out-of-pocket to access similar services. At the other end of the spectrum, Sweden provides a much broader population segment with a wide range of coverage at minimal out-of-pocket costs—but per-capita public spending on health-related social care is much higher.

Some countries tackle social-care funding shortages in other ways. Australia has developed a tax-funded system, and England recently announced tax increases to plug the funding gap for social care. Ireland has a consolidated procurement process for health and social care to ensure budgetary control and financial sustainability.

Integrated health and social services give governments an opportunity to target services more effectively and thus spend more efficiently.

Social-care workers should undergo professional training and licensing, with regulatory oversight from government. The UK's Social Care Institute for Excellence provides training, consultancy, topic expertise, and research to empower and increase the capabilities of social-care teams. Social workers undergo periodic examinations to renew their licenses, and the system includes reporting protocols to ensure that care meets quality metrics, along with a mechanism for patients to register complaints of substandard care.

The last enabler, technology, is an important means of improving awareness of the quality of care being delivered and received. Telemedicine platforms increase access to care, and data from those platforms increases the visibility of outcomes. Health systems also need to put data into the hands of both patients and health and social-care professionals. This can provide patients with helpful information (such as when a prescription is ready for pickup or delivery) and alert caregivers to problems (such as a patient's failure to attend physical therapy due to a lack of transportation) that they can then address to improve care. Sweden’s national health and social-care service features a web platform that allows practitioners to see patient outcomes around the country. This data transparency has helped providers identify and adopt best practices, leading to higher-quality care in Sweden than in countries where the technology isn't yet in place.

With the emergence of social-care systems globally, the time is ripe for governments to consider integrating them with their health care systems. In doing so, they can ensure that resources are used most effectively and generate the biggest positive impact on the health of their citizens.