F&L companies can ensure access to key materials and components without raising costs or reducing responsiveness.

Fashion and luxury (F&L) supply chains have never had it so hard. The pandemic, extreme weather events, and geopolitical uncertainty—combined with growing demand for sustainability—have constrained supply, increased costs, and made responsiveness much tougher to achieve. Unless F&L companies dramatically transform where and how they source products, these supply chain management challenges are likely to grow worldwide.

Yet adapting the sourcing footprint is not an easy task. The options are limited, the time needed to make changes in the sourcing network is lengthy, and after decades of using the same suppliers, organizations are generally inexperienced and ineffective at implementing new strategies.

To make a real difference, it’s critical that fashion companies take a bold and more holistic approach that may seem counter to traditional logic. Three moves are key. Organizations need to simplify their products and the overall portfolio, modernize their production system, and geographically diversify their sources of supply.

Frustrating Times for Fashion Supply Chains

Although few supply chains have escaped the events of the past two years unscathed, the supply chains of F&L companies have been especially hard hit because of their inherently long product lead times and geographic concentration of suppliers.

According to BCG research, the product lead time of average companies is 37 to 45 weeks. While many players have announced efforts to shorten lead times over the past ten years, progress so far has been relatively modest.

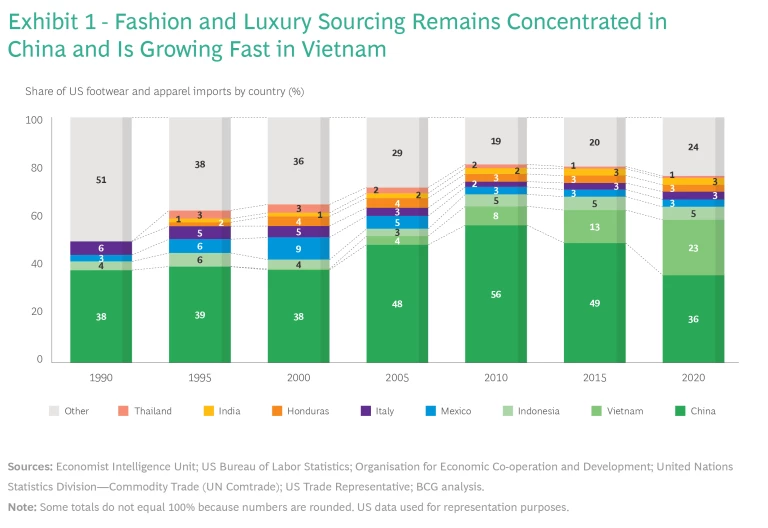

And the geographic concentration of suppliers has only exacerbated this challenge. Ten years ago, more than half of F&L sourcing took place in China owing to the low cost of manufacturing there. (See Exhibit 1, which uses US data for representation purposes.) As costs in China rose, many companies diversified their sourcing network, partnering with suppliers in Vietnam, Indonesia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Even so, over 50% of total volume today comes from just two countries: China and Vietnam.

Three Strategies for Success

It’s fair to assume that F&L supply chains will remain constrained, costly, and inflexible long after COVID-19 and current geopolitical tensions are resolved. Three levers will be critical for improving performance.

SIMPLIFY PRODUCTS AND THE OVERALL PORTFOLIO

Reducing the complexity associated with the product assortment, both the number of products and the number of components required for each, will be essential for lowering supply chain costs and risk. That’s because product complexity translates directly into manufacturing complexity—the number of processes, systems, and so on. And greater manufacturing complexity constrains productivity and, by extension, diversification given that the per-item investment needed for moving smaller volumes is higher. A few key strategies can help:

- Segment and rationalize the collection. Companies should design a different process creation pipeline for each type of product, depending on its segment (fashion, seasonal, or core). The collection should be assembled to optimize profitability and units of needs, homogenous groups of products that meet a specific consumer requirement. This approach reduces the collection to the SKUs that bring the most traffic, profitability, or both. Doing this in a systematic and data-driven way will help keep the portfolio in a healthy place—and avoid the need for periodic cleanups that most companies face today.

- Predefine components. To reduce product variance and ensure production feasibility, it’s important to develop a short list of preapproved fabrics, colors, and master patterns. That’s because limiting the component options helps minimize risks associated with quality and compliance. Best-in-class players that have enough scale leverage standardized materials from a database of all fabrics and trims that proactively provides recommendations.

- Design for value. Companies should break down each product into functions, assessing the value of each function in the eyes of the customer and in terms of its complexity. This approach helps in identifying the components that add the most value for the customer and deprioritizing components whose complexity is greater than their value-add.

While none of these strategies is new, they have assumed a greater level of urgency as supply continuity, resilience, and sustainability become critical necessities.

MODERNIZE THE PRODUCTION SYSTEM

F&L companies have let their partners determine the setup of facilities without providing much guidance. Consequently, most facilities produce many kinds of products, ranging in volume and innovativeness. A highly assorted product mix makes it easier for partners to keep their facilities fully loaded, but it lowers overall productivity because facilities can’t focus on any one segment. Additionally, there is little standardization between facilities, so it’s difficult to launch new ones rapidly in new locations—a vital prerequisite for greater productivity and diversification. To remedy these issues, companies should:

- Segment facilities. First, F&L companies should define the types and quantities of facilities that are needed (high volume, low volume, and flexible). The next step is to segment the facilities in the network (including a company’s own plants) and clarify the role each should play according to the product portfolio and capabilities required for optimizing the overall impact.

- Specialize the operating system. Companies then need to develop a facility operating model for each segment, with Industry 4.0 technologies driving performance improvements. We recommend using a line-centric model, which is based on the production line and its team. All operating best practices and latest technologies should be brought to bear to maximize the effectiveness of the line, using digitization partners when necessary. At the same time, the team must be provided with the skills and authority needed for improving performance over time. Once the lead line is established, the model can be applied to other lines in the same facility and eventually to other facilities. Because the operating system is well defined and documented, the scaling process should go quickly.

- Collaborate across the ecosystem. To improve resilience and performance, companies need to make an important shift—from communicating with partners to collaborating across the entire partner ecosystem. Next-gen leaders are actually going inside their suppliers’ plants to help drive innovation and joint value creation. Players with more advanced digital capabilities can enjoy near real-time connectivity with their partners, leveraging high-quality data to jointly solve problems that impact the supply chains of one or multiple partners. They could, for example, work together to manage a disruption at a common supplier or implement or optimize a new technology. They could even benchmark performance against one another, a common practice in other industries such as automotive.

Companies that implement the line operating system well should see their entire network of facilities operate in a consistent and highly capable way.

DIVERSIFY INTO NEW LOCATIONS

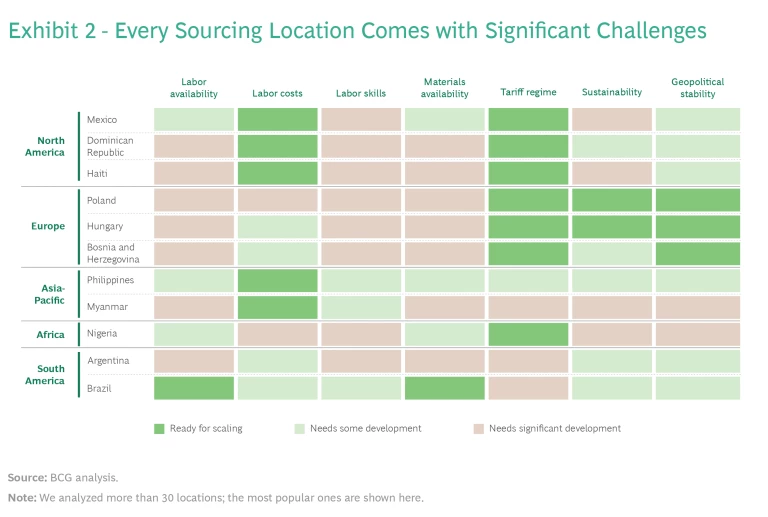

With the savings generated by facility modernization, companies can diversify their sourcing networks geographically, which is a much more challenging task than it used to be. In the past, this effort required balancing costs and production capacity while maintaining a certain level of quality. Today, many more criteria must be factored into the equation, including access to raw materials, low tariffs, the ability to meet sustainability targets, and respect for human rights.

Our analysis of more than 30 popular locations found that none, in fact, meets all these different criteria. (See Exhibit 2.)

Many companies try to address these challenges with near-sourcing. Historically, this was a way to manage demand for product categories where the demand was more volatile and harder to predict. Putting production nearby reduced lead times, lost demand, and inventory costs. It was also a way to decrease the use of long-haul transportation that can raise a product’s carbon footprint.

To make the best diversification decisions, five levers are key:

- Build a data and analytics foundation. To evaluate sourcing options, companies need to develop a comprehensive framework for evaluating supplier attractiveness and modeling future scenarios. An analytical review will provide an understanding of the breakdown of cost components needed for modeling costs from different sources. Analytics are also invaluable for assessing the various dimensions of risk, such as geopolitical turmoil, natural disasters, partner failures, and reputation. A mathematical approach considering impact and probability can reveal the expected cost of each.

- Create a country- and category-level strategy. With these insights in hand, companies can design a plan for managing and scaling each geographic area and category. The sourcing evolution plan should include the target mix of locations as well as near- and long-term objectives. Nearshoring, new locations, and other footprint details should be included. Companies should begin by creating scenarios that make it possible to evaluate different countries by category. Using this information, they can then develop a high-level business case and overall case for change along with a high-level implementation plan. Detailed country development plans should follow, with a discussion of the implications for the partner ecosystem.

- Develop stronger and different partnerships. At the same time, F&L companies should support their big bets by starting to build strategic partnerships—with suppliers, government agencies, and other industry players—and developing cross-industry ecosystems. For each country category, companies should select their strategic partners on the basis of their capabilities and local relevance. (See the sidebar below.) A partnership model that is mutually beneficial is critical with strategic partners, particularly in new countries.

- Make sustainability a top priority. In the future, diversification decisions will increasingly need to factor in sustainability considerations, especially when it comes to the sourcing of raw materials. Companies will need to use traceability as well, to ensure that their value chain complies with sustainability regulations.

- Elevate investments. Companies also need to boost their investments to build scale and catalyze ecosystems. Such investments will help secure and expand the capabilities crucial for supporting future productivity requirements, from access to raw materials to sustainability. Countries with high potential may need to be developed in several dimensions. There are at least three solutions worth exploring: building country development plans with local governments, partnering with competitors to reach the volume of production that is cost competitive, and developing an ecosystem alone, from the bottom up.

A Global Apparel Company Reshapes Its Sourcing Strategy

To cut costs and ensure a reliable supply during this challenging time, the company created long-term strategic partnerships with a small number of raw-material providers and contract manufacturers. The vendors agreed to a one-time rebate to prove their commitment to the apparel company. If the apparel company met long-term process simplification objectives and volume commitments, the rebate would remain in place.

The pandemic had also made it all too clear that dependence on one region can be dangerous in times of global crisis. More than 50% of vendors had their operations in China, which presented some risk. The apparel company decided to investigate moving its sourcing efforts to suppliers based in Eastern Europe, which was closer to many customers. Although expenses there were higher, the company believed it could create an even stronger “made in Europe” customer value proposition, delivering the highest-quality products while keeping costs under control.

Working with its strategic suppliers, the company undertook detailed scenario modeling to understand the total cost implications of shifting the majority of sources for its key categories. This analysis included the costs of materials, contract manufacturing, freight, and duty. Although contract manufacturing and material costs were higher in Europe, freight and duty were considerably lower.

There were good reasons to make the move. The company already sourced some of the components from Europe, so the shift would mean that manufacturers and material suppliers were closer to one another. Most important, Eastern European locations enabled greater agility and speed, given that samples could be shipped faster, suppliers visited more easily, and so on.

The company then did an in-depth assessment of Eastern European countries along seven dimensions, including quality, cost, agility, and sustainability. After understanding the various tradeoffs, the company identified the country that would be most suitable for sourcing. Today, the company and its existing partners are investing in that nation as a country of origin.

Getting Started

None of this is easy: organizational inertia, the unsuitability of existing partners for new locations, and the lack of viable new partners all pose challenges. Consequently, building capabilities in new locations requires considerable and consistent investment. Large-scale transitions can take five to ten years to complete—and that’s when only a few countries are involved. Companies that try to source in too many new countries at once won’t see results for even longer.

To mitigate these challenges, we recommend that companies:

- Estimate the size of the prize. It’s critical to consider both the value to be captured and the potential cost of inaction.

- Assemble the right team. The group that drives this initiative should be cross-functional, with specialists in traditional sourcing, sustainability, and operational excellence, among other areas. In addition, the team needs the right skills, including analytics, risk quantification and management, partner development, advanced manufacturing, and Industry 4.0. And it must have an innovative mindset that challenges old ways of thinking.

- Set ambitious goals. Given the inherent organizational inertia, it’s important to establish bold targets—that’s the only way the team can muster the momentum needed to drive substantive change.

Companies that underreact to the challenges could see further deterioration in their contribution margins and risk profile. But overreacting carries its own set of caveats. Relocating to too many relatively expensive countries can damage the company’s competitive cost position and excessively raise capital expenditures.

For example, companies should resist the temptation to move their sourcing entirely out of China. Although labor costs in the country are rising, China has distinct structural advantages, so it will likely continue to be the manufacturing innovation leader. The F&L sector there has deep experience and receives abundant external funding. Moreover, many Chinese conglomerates own their own plants abroad.

At the same time, it’s important to keep in mind that diversification to low-cost countries is not a panacea. Companies need to use technology innovation to get more from their existing partners.

The future of fashion sourcing will look very different than it does today. It will be less complex, increasingly capable, and more geographically diversified. The players that make the effort to forge that future now will be the ones that win tomorrow.