Any hope of reaching

net-zero

global emissions rests on decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors such as power, industry, heating, and transportation. And two emerging solutions—low-carbon

These solutions come at a significant cost. We estimate that up to $13 trillion of private-sector investment in hydrogen and CCUS will be required to achieve the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) “net-zero emissions by 2050” scenario.

Thus far, however, banks have not provided the debt financing necessary for these two technologies to scale up. Why is that? To answer this question, we surveyed over 100 experts and interviewed more than 35 executives from commercial banks, development banks, private equity firms , asset managers, and energy companies.

While commercial banks are keen to finance hydrogen and CCUS projects, they are holding back because of the perceived risks involved.

We found that while commercial banks are keen to finance hydrogen and CCUS projects—both to support their clients and meet their own sustainability targets—they are holding back because of the perceived risks involved. And because most banks aren’t prepared to be more flexible with their project-finance risk criteria, many projects are simply not going ahead. Some 80% of announced low-carbon hydrogen projects worldwide are still in the planning stage, while only about 7% of CCUS projects have reached the final investment decision (FID) stage to date.

We believe this is a missed opportunity. The economics of hydrogen and CCUS projects will continue to improve as the underlying technologies mature and policy support increases. Over time, many more projects will come to match the risk profile banks are looking for and become “bankable.” In the meantime, banks that are willing to be flexible and seize the opportunities available today stand to benefit from a sizeable early-mover advantage.

Lending for Hydrogen and CCUS Projects Is Limited—for Now

According to IEA estimates, the world will need to produce 540 million tons of hydrogen and capture between 4 and 8 gigatons of CO2 each year to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This translates into a cumulative investment need of about $10 trillion in hydrogen projects and as much as $3 trillion in CCUS

Banks are factoring hydrogen and CCUS into their medium-term green lending plans. Our survey found that 75% to 80% of commercial banks expect the two technologies to make up over 10% of their energy-related portfolio by 2030. At present, however, most banks aren’t providing nonrecourse debt finance to hydrogen and CCUS projects.

Our research suggests that many commercial banks are waiting for these projects to meet the same standards and provide the same levels of risk as more developed green projects, such as solar photovoltaic (PV) parks and wind farms. Banks want the projects they finance to:

- Have long-term offtake agreements with good quality counterparties (offtake risk)

- Use mature technologies (technology risk)

- Operate under clear regulations and industry standards (policy risk)

- Be able to sell into established markets (merchant risk)

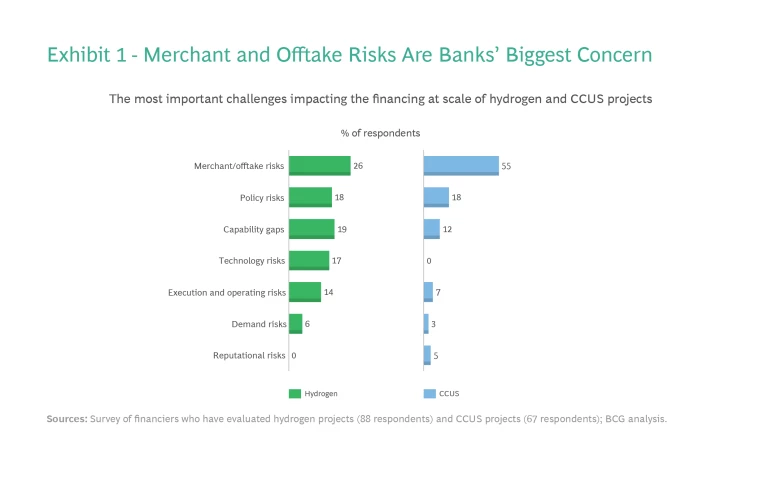

Hydrogen and CCUS project developers can’t currently provide the same degree of certainty in these areas. Our survey found that when it comes to hydrogen and CCUS projects specifically, banks were most concerned with offtake and merchant risks. (See Exhibit 1.)

A Unique Set of Challenges

Policy changes and technology advances have revolutionized the renewables sector over the last two decades, bringing greater cost efficiency and production capacity and making projects more bankable. We expect many of the same forces to transform hydrogen and CCUS projects in the coming years. But these emerging technologies face different challenges than renewables, and they will need to evolve in different ways.

For starters, renewable-energy project owners sell the power they generate into an existing electricity market. But because hydrogen and CCUS still lack an established marketplace—and because they involve molecules rather than electrons—offtake arrangements are less straightforward. For example, when it comes to using hydrogen to make green ammonia, production facilities for both hydrogen and ammonia typically need to be located next to each other due to transportation problems.

There is also a chicken-and-egg situation between users and suppliers of hydrogen. Potential users (steel producers, for example) point to cost considerations, such as the premium they must pay for hydrogen, and inadequate supply

Hydrogen and CCUS projects face different challenges than renewables, and they will need to evolve in different ways.

Other specific risk factors for hydrogen and CCUS include the absence of international agreements on what constitutes green hydrogen and on permanent CO2 storage, underdeveloped markets for trading hydrogen and carbon credits, a lack of clarity on liabilities and liability transfers relating to CO2 storage, and significant variations in CCUS regulations by region.

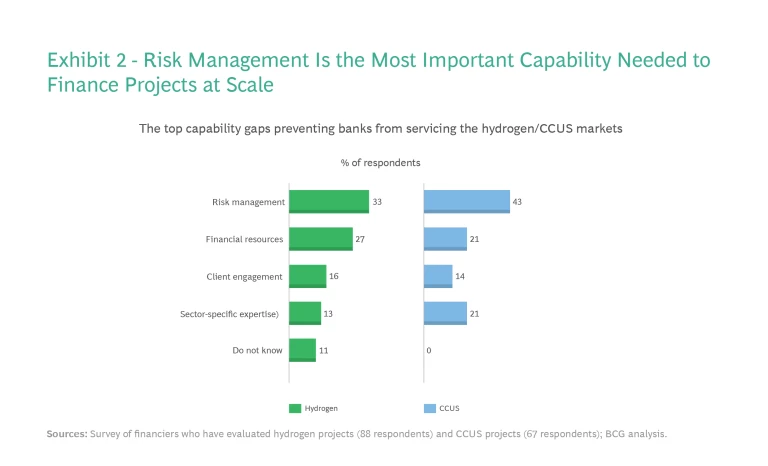

In the face of these challenges, banks need to have strong risk assessment and management capabilities in order to service emerging hydrogen and CCUS markets effectively. However, our research found that risk management was the leading capability gap preventing commercial banks from financing these markets at scale. (See Exhibit 2.)

Despite developing the necessary understanding and risk tools for renewables over the past two decades, banks lack the models and data for gauging the risks of hydrogen and CCUS projects. Banks that want to build an early competitive advantage in these markets should prioritize the development of these capabilities along with relevant technology and policy expertise.

Attractive Projects Will Become More Plentiful

Policy measures, such as the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the European Union’s REPowerEU plan (reinforced in February 2023 with the EU Green Deal Industrial Plan), are set to improve the economics of hydrogen and CCUS projects and make them more bankable.

The incentives and regulatory approaches involved differ. The US’s policy approach is based on tax incentives and less regulation, whereas the European approach is structured around regulated-asset-base models, contracts for difference, and carbon markets such as the Emissions Trading System. By removing elements of risk, both approaches are providing players with greater certainty through well-known and financeable business models. We expect these policy approaches to be replicated in other markets, creating new funding opportunities for banks.

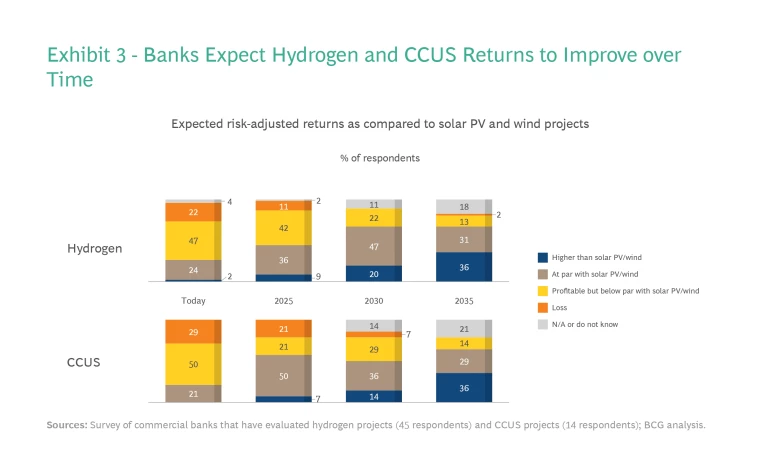

Banks expect that the number of commercially attractive projects, while few and far between today, will increase over time because of these policy trends. We found that 50% of banks anticipate risk-adjusted returns for CCUS projects will be equivalent or better than solar PV and wind returns by 2030, while 67% of banks expect the same will be true of hydrogen projects. (See Exhibit 3.) By getting in early, banks can select the best ones.

Equity providers are also likely to benefit from participating early, judging by the performance of the renewables sector. By analyzing returns from solar and onshore and offshore wind projects between 2010 and 2020, we found that unleveraged returns fell on average by between 6 and 9 percentage points over that period as more investors entered the market.

Banks that do move early could find it’s an opportune moment for other reasons. A majority of the banks we surveyed believe that the war in Ukraine, and the resulting concerns about energy security, will cause capital to be diverted from hydrogen and CCUS projects to traditional oil and gas projects for at least the next two years. This leaves the field open to banks with ambitions to build on hydrogen and CCUS financing opportunities created by green policies in the US and Europe.

Early Movers Can Secure a Leadership Position

Banks that want to lead in hydrogen and CCUS financing shouldn’t wait until technology and policy improvements bring greater maturity to these markets. They need to act now, adopt an innovative mindset, and invest in new capabilities and know-how.

Banks seeking to fund hydrogen and CCUS projects need to act as ecosystem enablers.

To be a successful early mover, banks seeking to fund hydrogen and CCUS projects need to act as ecosystem enablers, build relationships across the value chain, and bring together different stakeholders—from export credit agencies and development banks to insurers and developers. In doing so, early movers can shape the space together with these other key players. Once an early-mover bank builds partnerships in a specific area, the collaboration opportunities for followers are few.

Most banks have not explored different financing options that could be better suited to these emerging technologies. Consequently, most completed projects to date have been financed by their owners or by equity investors, including private equity firms and offtakers such as chemical and utility companies, rather than banks. However, we’ve found that successful early-mover banks are using alternative financing options, such as equity investments and (in the US) tax equity finance, and are exploring mezzanine finance.

These involve greater risk than traditional debt-based project finance. But by building knowledge from early deals, banks can capture opportunities, manage risk better, and offer better pricing. Furthermore, because this approach doesn’t necessarily require a big balance sheet, it could enable smaller regional banks to become significant players—especially in cases where regional banks have a good understanding of the local market and policy environment, a solid understanding of the technologies, and strong existing relationships with energy sponsors and developers.

Successful early movers also benefit from a virtuous circle: those banks that do it right will get the calls to finance the next deal.

Here are other steps that are key to being a successful early mover:

- Having the right attitude to risk and capital is essential. You don’t create a competitive advantage for free, and there is a strong chance that, as an early mover, you’ll make expensive mistakes. But, as equity providers in the renewables sector demonstrate, early movers will put themselves in a position to earn attractive returns.

- Developing in-house expertise and knowledge is critical for managing risk and originating deals. Knowing how to structure partnerships and attract the right partners is a key capability for becoming an ecosystem enabler. This is a new environment for banks, but one where they are well positioned to succeed.

- Banks can’t serve all aspects of these new markets. They need to create a framework so that they can select where to play effectively. Choosing projects that replace existing gray hydrogen (produced from fossil fuels) with green hydrogen, for example, and targeting more mature use cases, such as green ammonia production, are a less risky starting point. If done right, this framework will direct early-mover banks to areas where local market demand meets their organization’s DNA. At the same time, energy players should actively consider partnering with financial institutions in these areas.

- Finally, banks should protect the bonuses of employees working in emerging hydrogen and CCUS markets—where the potential for immediate returns might be limited—and adjust team KPI targets if those employees are to be properly motivated.

Barclays is one example of a bank that is adopting a more innovative approach to funding hydrogen and CCUS businesses. The bank’s Sustainable Impact Capital portfolio, which is run by its principal investment team, has invested equity in Protium, a UK developer of energy solutions using green hydrogen, and MOF Technologies, a northern Irish carbon-capture company.

A number of banks are also providing finance indirectly by supporting public-private investment initiatives for hydrogen and CCUS. For example, HSBC invested as an anchor partner in Breakthrough Energy Catalyst, which is investing in direct air capture, clean hydrogen, long-duration energy storage, and sustainable aviation fuel.

Subscribe to our Energy E-Alert.

The Role of Project Developers

Hydrogen and CCUS project developers can also take proactive steps to reduce risks, thus making it easier to secure bank financing. They can limit construction risks by insisting on a “full wrap” contract with their engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contractor, meaning the contractor assumes liability for all three elements. They can leverage grants and partner with development banks and export credit agencies to give their commercial lenders greater assurance. And they can develop long-term offtake contracts with reputable counterparties.

The developers of the Centrale Electrique de l’Ouest Guyanais, a green hydrogen power project in French Guiana, mitigated risks in these areas to get financiers on board. It has a 25-year power purchase agreement with France’s state-owned utility, EDF; it used an established contractor, Germany-based Siemens, for the EPC element of the project; and, by serving a small catchment area, further reduced project risks.

Similarly, the NEOM green hydrogen project, which is under construction in Saudi Arabia, has benefited from a 25-year offtake agreement with Air Products, the US chemicals and gases company. Air Products has a stake in the project and has assumed the commercial risks of transporting, storing, and finding end users for green ammonia (made from hydrogen produced by the NEOM plant) in order to become a market leader.

Hydrogen and CCUS technologies are essential decarbonization solutions for hard-to-abate sectors. And while most banks haven’t yet shown the risk tolerance to finance projects in these emerging areas, a golden opportunity exists for those prepared to be more flexible. Early movers can understand project risks better, enjoy higher returns, capture key relationships across the value chain—and gain share in two important and growing markets.

Banks that want to lead in this space cannot wait for the market to come to them with all potential problems solved. They must go to the market—actively helping to create, shape, and win future opportunities.