The auto industry is in a period of significant upheaval. Increased risk and shocks in the supply chain are complicating the industry’s efforts to introduce major technological changes to vehicle design. The initial blow was dealt by the COVID-19 pandemic, which was followed by the semiconductor shortage. These interrelated crises have caused unprecedented disruptions to auto industry supply chains, exposing the industry’s vulnerabilities and lack of risk visibility. The result: approximately 12% of global automotive output vanished from 2020 to 2022.

Even as the auto industry works to recover, risks relating to

semiconductor demand–supply imbalances

persist. Chip content per vehicle is anticipated to grow by approximately 7% annually. Although additional semiconductor production capacity is expected to come online, certain types of nonlogic chips (namely, analog and

Given the impact of recent supply chain woes and uncertainty surrounding when the volatility will subside, auto industry executives are increasingly seeking new methods to anticipate risks across the supplier spectrum and secure critical parts, commodities, and materials. The renewed urgency is buoyed, in part, by the accelerating shift to electric vehicles, which is adding many new suppliers and component types.

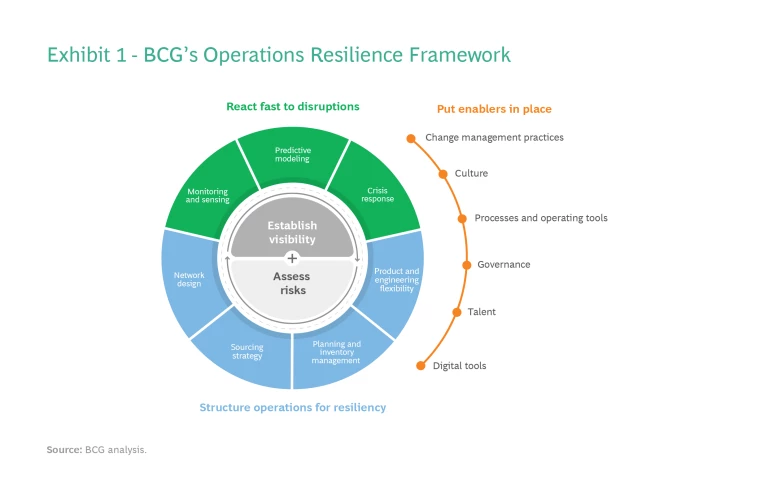

To facilitate these efforts, BCG has developed a framework that companies can use to proactively identify and avoid risks whenever possible and to absorb and mitigate risks if they occur. This approach encompasses a company’s operating model, including metrics, planning and sourcing processes, risk modeling, contingency planning, information flows, and supply chain collaboration.

BCG’s Resiliency Survey

Resilience is critical to weathering business challenges. Complete BCG’s Resiliency Survey to learn how your organization compares with peers across 10 capability dimensions.

Longstanding Practices Impede Effective Responses

In working with auto OEMs and suppliers, we have observed several supply chain shortcomings that have made it difficult to navigate disruptions. Supply chain systems and management practices have long favored optimizing operations by making supply chains as lean as possible, while simultaneously pressuring suppliers to reduce costs and inventory. Current just-in-time approaches leave little buffer to absorb disruptions.

Compounding the issue, companies lack adequate supply chain visibility. Supply chains have become so complex that automakers are frequently unable to identify suppliers beyond tier one. As a result, automakers do not know these suppliers’ manufacturing locations, lead times, and production and shipment track records—or even the parts or materials they supply.

During the semiconductor shortage, lean supply chains and the knowledge gap stymied response efforts and the ability to manage stable production schedules. Auto companies spent significant time early in the crisis simply trying to gain visibility into the layers of their supply chains. A BCG analysis using a web scraper to search for keywords (such as “semiconductor,” “shortage,” and “scarcity”) in local languages found that alerts and news about chip shortages began to surface in the second quarter of 2020. However, automakers did not begin to implement strategic responses for another six to nine months.

Some auto OEMs were better prepared than others and, although they were affected by the chip shortage, they clearly outperformed. For example, BMW and Tesla fared better because they had developed strategies to mitigate potential disruptions. They also went beyond their tier-one suppliers to establish relationships and volume commitments directly with chip manufacturers. When the crisis came, the better-prepared OEMs experienced lost unit volumes of less than 10%. Those that were slow to react suffered volume losses of 15% to 25%.

Subscribe to our Business Resilience E-Alert

A Framework for Resilience

To address these challenges, auto companies must build resilience—the ability to quickly identify and assess risks, respond quickly, and absorb the impacts of disruptions across the supply chain. BCG’s operations resilience framework covers the wide variety of capabilities required. (See Exhibit 1.) The two main aspects of the framework are reacting fast to disruptions and structuring operations for resilience.

React Fast to Disruptions

Responding quickly to a crisis requires proactively identifying risks to avoid them when possible, as well as having focused practices and team members to deploy when disruptions do occur.

Monitoring and Sensing.

Gathering risk information from both internal sources (such as procurement, logistics, and manufacturing) and external feeds provides intelligence that companies can analyze to create risk thresholds and sensing algorithms. In supporting companies, we have found several lenses for visualizing risks to be particularly helpful. These include supplier risk mapping, commodity and parts risk mapping, and a multi-tier supplier network view. Companies can apply these views to assess specific risk parameters. This could include, for instance, identifying suppliers facing location-related risks arising from an outbreak of disease or susceptibility to extreme weather events. It could also provide a window into the likelihood of supply bottlenecks caused by a single upstream supplier’s inability to source a specific material.

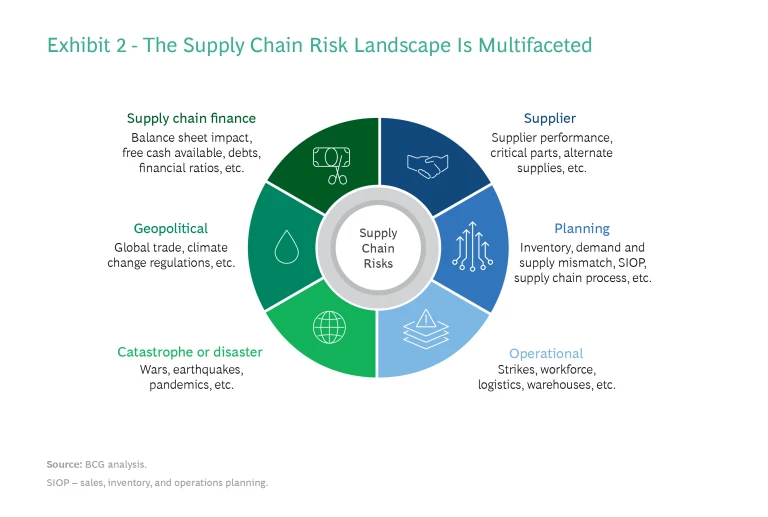

Access to data covering a wide range of risk categories is essential for risk monitoring and sensing. We have observed a significant increase in the scope of monitoring. For example, one OEM shared an overview of more than 30 risk categories, from geopolitical tension to the insolvency of individual suppliers. Exhibit 2 shows a selection of the leading risk categories.

Companies can glean information from structured data through the continuous monitoring of risk indicators from a variety of sources, such as trends in global cargo movement and commodity demand and supply. They can also gather it from unstructured data via web crawlers that look for keywords such as “shortage” and “shutdown.” A critical part of this intelligence gathering involves developing a comprehensive map of suppliers across all tiers and their interconnections.

Vendors of supply chain risk management platforms also provide curated information on worldwide risk events. Partnering with these vendors can help to accelerate risk monitoring and supplier mapping. This ongoing monitoring process requires collaborating with partners across the value chain, fostering trust, and investing in a set of data and visualization capabilities.

Predictive Modeling.

Dynamic models, such as digital twins , can assess a range of possible risk outcomes and play an important role in helping decision-makers develop their perspective on potential supply disruptions, the business impact, and how different actions can mitigate them. Understanding the implications of risks on overall business objectives is critical. Best practice is to identify the risks from the perspective of both the lost supply volumes and financial costs—and use this information to prioritize where to focus. In some cases, we have observed a scattershot approach in which companies dilute their attention across a multitude of risks with varying degrees of severity and time horizons, limiting the impact of the overall mitigation effort.

Crisis Response.

When significant risks do materialize, it is important to have a coordinated cross-functional response that enables rapid decision-making. This would generally involve purchasing, planning, manufacturing, logistics, sales, marketing, and finance. At the center should be a team that manages risk mitigation by coordinating and prioritizing activities, driving decision-making, and facilitating communications. End-to-end transparency across the value chain on incoming supply, operations schedules, logistics performance, and customer needs is critical to ensure an effective response. Additionally, the team managing risk mitigation should have frequent engagement with top executives to clear roadblocks and identify where executive-to-executive engagement is needed.

Structure Operations for Resiliency

The other half of our framework identifies levers to improve resilience within the supply chain, enabling companies to absorb and mitigate higher degrees of risk.

Network Design.

Companies should design and pressure test a supply chain against a range of disruption scenarios. By establishing risk visibility and comprehensively mapping the supply chain network in-depth—including customers, suppliers across tiers, and products—a company can proactively assess different types of disruptions and scenarios. It can identify where weaknesses and structural risks exist in the network, the severity of any potential impacts, and cost implications under each scenario. This enables the development of mitigation strategies and consideration of network options, such as reducing the concentration of manufacturing/supply base in higher risk regions and making future footprint and sourcing decisions using a “risk premium” for these locations. Applying a risk premium enables a more holistic assessment of the trade-offs between resilience and cost.

Sourcing Strategy.

Closely linked to network design, companies’ supplier selection process should include a method to evaluate sources of supply risk—such as supplier-related problems (financial, operational), tariffs, or transport route issues (port backlogs)—and the impact on resilience. In addition to identifying potential disruption scenarios, companies require greater transparency into the broader supply chain. As previously noted, detailed mapping of key products, components, and commodities across supply tiers is critical. With this in hand, companies can more holistically evaluate cost-versus-risk trade-offs, define risk tolerance, and develop aligned sourcing strategies .

Companies’ supplier selection process should include a method to evaluate sources of supply risk and the potential impact on resilience.

For example, one strategy could include investing in redundant capacity and establishing a faster process to ramp up alternative material sources, while monitoring risks and defining triggers to activate an appropriate risk response.

Planning and Inventory Management.

Building resilience requires having a sales, inventory, and operations planning (SIOP) process upgraded for risk management. For example, this includes risk sensing and scenario planning, executive engagement on risk trade-offs, increased transparency and communication with suppliers, and faster cross-functional decision-making.

Inventory planning is critical to protect against unexpected shocks and disruptions. Companies need to develop adaptive inventory targets with triggers that adjust inventory levels based on risk tolerance. When risks are heightened, the company builds buffers at appropriate stages in the supply chain to strengthen resilience. This is a dramatic contrast to the slow-moving adjustments and target setting in many of today’s supply chains.

Product and Engineering Flexibility.

Thoughtful product design that considers potential supply risks is important to avoid manufacturing disruptions. Engineering and product development teams need to incorporate risk scenarios into their design assessments. Possible strategies include increased use of common components and establishing a process to make rapid engineering changes and substitutions when disruptions and supply constraints arise.

During the semiconductor shortage, many OEMs had limited flexibility to shift to alternative suppliers or use substitutes for highly customized chips. This dramatically constrained their response options. OEMs were forced to prioritize which vehicles to produce and also reduce features—such as heads-up display—or build and hold semi-finished vehicles pending arrival of the missing components.

BCG’s Resiliency Survey: Auto Companies Report Lagging Performance

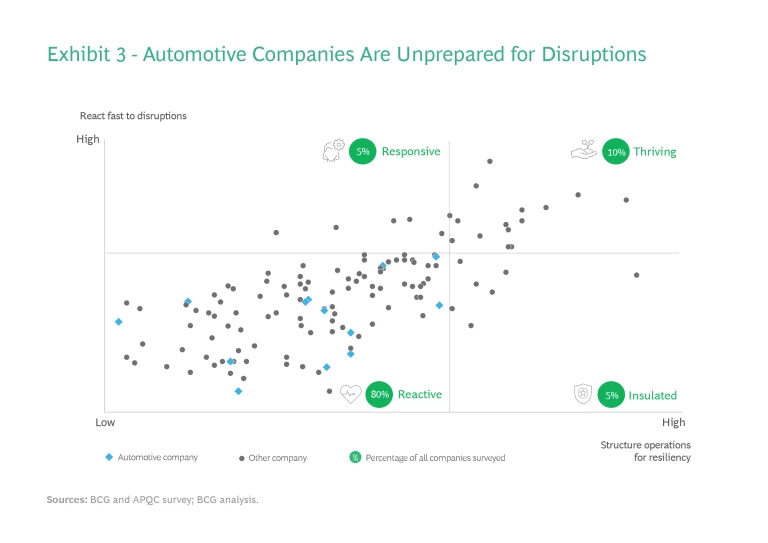

In the summer of 2022, BCG and APQC fielded a global survey of 150 companies across various industries to assess their capabilities relating to the elements of the resilience framework. Based on their self-reported responses, we gave each company a score and placed it on a resiliency matrix divided into four quadrants: thriving, responsive, reactive, and insulated. (See Exhibit 3.)

Across all industries, only 10% of respondents are thriving companies that excel in all dimensions of the framework. Among the thrivers, there were several from the electronics, industrial, pharmaceutical, and consumer sectors. Notably, 80% of respondents, regardless of industry, are reactive: they are unprepared to quickly address disruptions that may occur, and their operations are not structured for long-term resilience.

Automotive respondents, both OEMs and suppliers, are all in the reactive category. These companies self-reported low maturity with respect to their capabilities to react fast and the fitness of their operations to absorb disruptions.

A substantial number of auto companies fall short of employing best practices for monitoring supply chain risks. Most thriving companies use advanced analytics (including AI) to continually monitor and evaluate risks in their network. However, only 15% of auto companies surveyed have these capabilities.

Among auto respondents, 35% report having low risk visibility and ad-hoc manual communication with customers and suppliers. The same percentage report using manual or static tools to collect data from vendors regularly. Only 30% have two-way communication with suppliers through a digital or real-time application and interface.

In addition, 70% of auto companies reported lacking an adequate playbook for responding to disruptions or a crisis response team that can be activated quickly. Thriving companies, on the other hand, have a strong and dynamic playbook, with embedded risk and resilience capabilities to address complex disruption scenarios.

Auto companies also report lacking robust sourcing strategies that embed resiliency. The majority of auto companies surveyed primarily select suppliers based on cost. In addition, these companies report an inadequate multi-sourcing strategy. Only 30% identify critical sub-categories and deploy multi-sourcing strategies and rapid recovery plans based on risk.

Many auto companies lack robust supply and demand planning processes. While thriving companies use advanced analytics to build predictive demand forecasts and set inventory targets, auto companies struggle with low forecast accuracy and lack a robust process for setting inventory targets. Even auto companies that report having more robust planning processes noted they could do more to break down silos and increase cross-functional collaboration and executive engagement.

Finally, auto companies need to strengthen their design and engineering capabilities to promote flexibility and agility. A majority reported that they use custom components for most new products and lack modular designs that allow for more flexibility of component usage. Although most auto companies report having a standard engineering and design change process, many are unable to expedite and approve design changes quickly enough when a supply crisis arises.

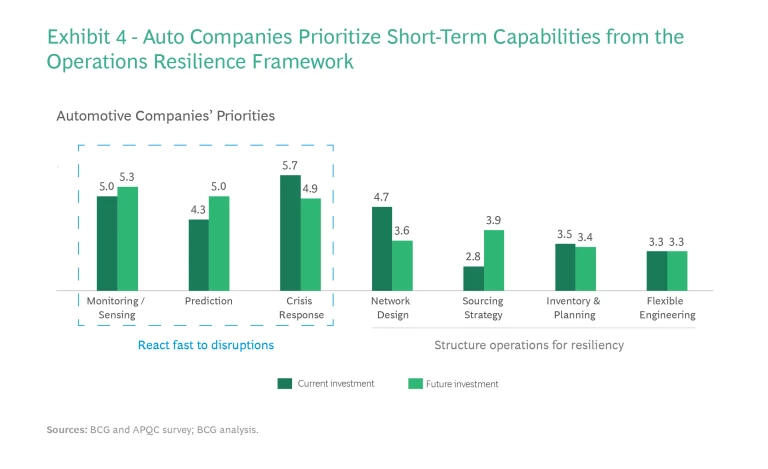

Auto Companies Are Prioritizing Investments in Crisis Response

The survey also asked respondents how they are prioritizing near-term versus long-term issues. Auto companies reported focusing on improving near-term crisis response—the “react fast” half of our framework—while giving much less attention to longer-term resilience. (See Exhibit 4.) This emphasis is understandable considering that companies are still stinging from their lack of preparedness for the supply chain crisis of the past few years. However, increasing effort on long-term structural changes can help insulate companies against future disruptions, lowering the cost and impact of the next crisis.

A Roadmap for Resilience

Achieving a resilient supply chain is a journey, and like many other sectors, the automotive industry is just getting started. (See Exhibit 5.) To stabilize supply chains in the near term, auto OEMs and suppliers must first establish end-to-end visibility and incorporate robust risk-monitoring capabilities that utilize both internal and external data feeds. By implementing these capabilities along with risk KPIs and dashboards, companies can detect potential disruptions and react faster to risks.

Next, companies can reduce risks in the medium term by enhancing existing SIOP processes with scenario and trade-off analyses that are linked to risk monitoring across the supply chain. By regularly mapping the products and suppliers in accordance with their risk profile, companies can pinpoint where to dynamically add inventory buffers to strengthen resilience.

To create a structurally resilient future, companies should focus on sourcing strategies to de-risk critical materials and improve transparency and communication with customers and suppliers. Pressure testing the network and bill-of-material design for resilience based on risk scenarios is also important. Furthermore, companies should build flexibility into engineering processes and product design to allow for the use of alternative materials and substitutions and to develop accelerated design change processes to better respond to future disruptions.

Rewiring the Organization for Risk

Auto companies must prepare their organizations for risk identification and response by fully integrating resilience capabilities into their operating models. At its core, this requires strengthening business processes and managing organizational change to ensure that anticipating and responding to supply chain risk is integrated into core metrics and processes. Managing this risk should be an integral part of operational functions such as supply chain planning, procurement, and logistics.

A crucial first step is improving transparency across the supply chain and establishing mechanisms to trigger internal and external communications about potential problems. For example, executive performance metrics should include transparency to revenue at risk, which helps to provide a basis for prioritizing activities and investment. Developing the data foundations for transparency should not be postponed until the next crisis event, but instead pursued as an ongoing capability enhancement.

Finally, a cultural shift that prioritizes risk management may be necessary. For example, incentives can be adapted to reward proactive risk identification and early responses that protect the business. Additionally, recruitment and upskilling efforts should emphasize obtaining or building capabilities for scenario planning, advanced risk analytics, and data engineering. Advanced digital tools, such as AI-powered platforms, can enhance human capabilities and unlock new value sources, allowing organizations to better handle volatility.

The last several years dramatically exposed weaknesses in supply chains across many industries. Auto companies recognize that a sustained commitment to supply chain risk management is critical. To act on this commitment, they must move with urgency to prepare for future supply challenges. Ultimately, supply chain resilience could make the difference between success and failure in an increasingly competitive and radically changing environment.