The US federal government has made significant investments in IT across its agencies to catch up to technology adoption rates in the commercial sector. And while government IT is growing quickly in capability, it is also growing in cost. The Department of Defense (DoD) alone budgets over $45 billion annually to IT, and in 2022 President Biden called for an 11% boost in IT budgets for federal civilian agencies. Additionally, the number of technologies and products that the DoD is allowed to purchase has increased significantly, complicating the decision calculus and increasing the need to ensure optimized and intentional spend.

Federal agencies have made numerous efforts to deploy their IT funds more efficiently, from cost transparency and government-wide category management to agency-specific cost reduction efforts. Yet, substantive cost curtailment and spending improvements have been rare.

From our case experience, we have identified the leading issues behind this failure of US government agencies to generate IT cost improvement, especially when compared with commercial peers, across three key categories: budgeting and funding processes, savings program execution, and government constraints. And we offer five key strategies that can close the gap to commercial best practices and improve cost outcomes.

Budgeting and Funding Processes

Shadow IT. Whereas commercial organizations tend to focus on expenditures, government agencies focus on program budgets, with IT just one of many embedded components. This approach typically gives little visibility into “shadow IT”—IT spending that is hidden in adjacent budgets or vendor contracts. As a result, while the amount of money spent by each program is clear, the percentage allocated to IT is not, and senior government officials are thus unable to budget enterprise-wide IT spending effectively. In fact, when cost transparency is introduced, we often find that IT expenditures are up to 30% higher than anticipated due to this hidden spending.

Lack of Oversight. In commercial entities, the CIO or CFO typically controls most IT spending or at least has a high awareness of it. Business units cannot make major IT purchases without proper authorization, and shadow IT is one of the first targets of commercial cost-reduction efforts.

While the government has introduced a number of cost-transparency measures, there is still a significant lack of CIO oversight.

In contrast, while the government has introduced a number of cost-transparency measures, such as business management practices that align costs to IT services, there is still a significant lack of CIO oversight. With hundreds or thousands of budget holders in any given government agency and multiple contracting mechanisms, such as government-wide acquisition contracts and multi-agency contracts, many budget holders can make major IT purchases using these agreements with just the approval of a contracting officer, without CIO approval or awareness.

Budget Incentives and Risks. Companies focus on metrics such as overall ROI, payback period, and weighted average cost of capital when making business decisions. It is incredibly challenging for government leaders to do the same due to the higher risks associated with budget shortfalls. For example, the DoD might budget a large amount of money to be spent in year one with the aim of saving money in years two to five, but if the effort fails to deliver, there are much greater potential adverse effects from the budget shortfall in years two to five than would be the case in a commercial business.

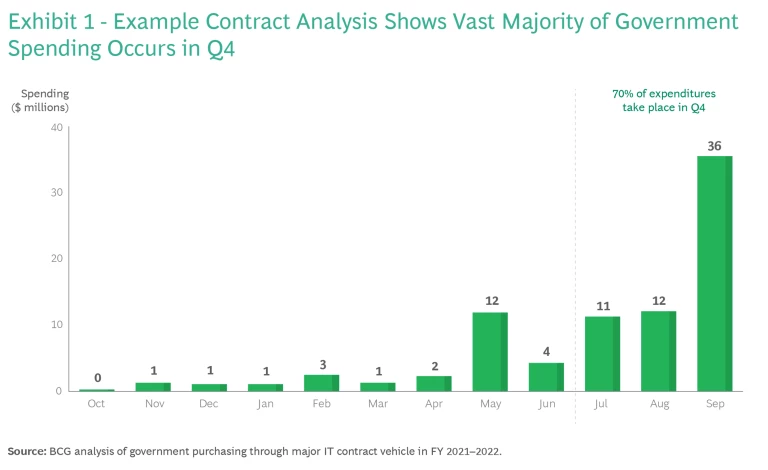

Additionally, agencies have much greater incentives to spend the annual amount budgeted to them, as those that do not do so not risk having it reduced in the following years. While commercial leaders also “spend to budget” to some extent, they do so to a much smaller degree because they are ultimately more motivated to maximize profits each year. As might be imagined, spending to budget leads to suboptimal purchasing behavior, including large spikes in spending on commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) IT in the final two months of the fiscal year. (See Exhibit 1.)

Savings Program Execution

Lack of Consumption Data. The analysis of consumption data is one of a corporate CIO’s most powerful tools, but government agencies struggle to obtain such data. Many government CIOs don’t know how many laptops or other pieces of hardware they purchased in the prior year, how many licenses of a given type are deployed on their networks, or the extent to which deployed licenses are regularly used. Without this baseline data, they cannot identify areas of underutilization where they might reduce costs. And it is extremely difficult to cut back on new purchases and license renewals without knowing whether it will adversely affect an agency’s mission.

Overreliance on Negotiations. Commercial CIOs are typically more successful in achieving savings through a mix of discounts and demand management than via negotiations alone. In contrast, many government cost-containment efforts focus primarily on vendor negotiations, often due to a regulatory split between the government’s procurement organizations and the organizations that generate the IT requirements.

This is true even though agencies may not be able to negotiate with strength, given the lack of insight into their own consumption. If an agency does not know how many licenses it actually needs, for example, it has little room to maneuver by purchasing fewer licenses or shifting a portion of the user base to a less expensive license.

In addition, agencies typically lack insight into their IT providers’ business models that they could use to their advantage. Commercial vendors deeply research the opportunities and the organizations they are selling to, given that they are financially rewarded for winning work and maximizing profitability. But government contracting officers are given incentives for complying with regulations and establishing contracts in a timely manner. They also tend to deal with numerous commercial bidders, making it more challenging to understand the nuances of each firm. This removes the potential for savings that might be gained through conducting the negotiations with high-quality information about their counterparts. Instead, they must focus on getting a deal done on schedule while satisfying mission requirements and staying in budget.

Finally, a common vendor tactic is to move slowly enough to ensure that negotiations conclude as closely as possible to the end of a contract, knowing that the government has a low risk appetite, that there can’t be any gap in service, and that contracting offices are primarily evaluated on timeline performance.

Government Constraints

A third key issue that limits agencies’ ability to control IT spending is the government’s unusual way of working vis-à-vis commercial entities; in particular, cumbersome contracting regulations and extensive customization requirements.

Unique Contracting Regulations and Ecosystems. For vendors, working with the government is significantly more complex and inefficient than working with commercial partners. For example, unlike typical commercial contracts, government contracts usually include indemnity clauses that could theoretically cost vendors billions of dollars—a significant contracting hurdle.

To protect themselves, IT hardware and software producers typically use value-added resellers to sell or distribute their products to the government, paying them a fee that is often passed on through higher pricing. Other complications include reporting requirements and decision protests (that is, the right of vendors to protest a defective bid or a contract awarded to another player). And government buyers sometimes request multiple agreements per agency, with significantly longer timelines (and protest concerns) for establishing agreements. These inefficiencies have a significant cost for vendors, which can also be passed on through higher pricing.

Customization Costs. Government organizations are known for purchasing COTS IT solutions and then customizing them heavily during deployment, often because of perceived distinct requirements or because using COTS solutions would require business-process changes that the government does not want to undertake. Unfortunately, customization increases timelines and costs during deployment and, over the long term, creates an even larger problem as subsequent customizations boost complexity (and reduce functionality), leading to higher maintenance costs.

Strategies for IT Cost Control

Some government challenges—such as the need to work within government contracting rules—are immutable. In other cases, the costs, and risks, of transforming a heavily customized system are simply too high. Nonetheless, agency CIOs can address many of their challenges through sustained, determined efforts if they first lay the proper groundwork. Our experience highlights five key strategies.

Agency CIOs can address many of their unique restrictions and challenges if they first lay the proper groundwork.

Note that CIOs should not expect to use all the initiatives offered here. Rather, they should prioritize them and ensure up front that they have the leadership agreement required to follow through and deliver change.

Take a portfolio approach. If agency CIOs are to justify investments to reduce IT costs, given the inherent risks, they need to create highly detailed forecasts that go well beyond ROI. These should include, at a minimum:

- Estimates of where the impact will be realized (for example, in the CIO’s budget or in its shadow IT spending)

- Whether the impact will be the avoidance of a previously projected spending increase or the achievement of a net decrease in spending

- The years in which the investment will be required and those in which the savings will be realized

Detailed forecasts will help the CIO take a portfolio approach to the agency’s cost-savings initiatives—looking at its IT investments as a whole—and manage timing and risk in budget cycles. For example, cost reductions should start with quick wins to realize immediate impact and begin funding the journey. As cost-reduction efforts increase, agencies should balance higher-impact, longer-term, and more difficult initiatives with ongoing initiatives to maintain momentum and ensure a positive cash flow.

Note that the right contracting strategy is also important to funding the investment journey. With a “fees-at-risk” contracting structure, for example, the government can establish a contract with a minimal upfront fixed fee that ties the majority of the vendor’s fees to savings targets. This structure perfectly aligns the government’s incentives and those of its vendor support team; in addition, if savings targets are not achieved, the government’s investment costs are greatly reduced.

Target the most entrenched contracts. Most agencies have at least one large contract with an entrenched provider delivering a mission-critical good or service. Given its unique offer or expertise and its deep understanding of the government organization, the vendor appears to have all the power in negotiations. Not surprisingly, the government tends to avoid renegotiating these contracts, and the vendor is able to increase its margins over time. This is a fairly common predicament for any organization, but especially for the government.

While renegotiating these incumbent contracts may appear challenging, it is worth remembering that they are often the vendor’s most profitable contracts. Government agencies can level the negotiation playing field by developing their own information advantage—establishing an analytic baseline understanding of the vendor and the contract and executing a rigorous negotiation plan. Depending on the contract type, some government agencies have achieved savings of 15% to 20% in this way.

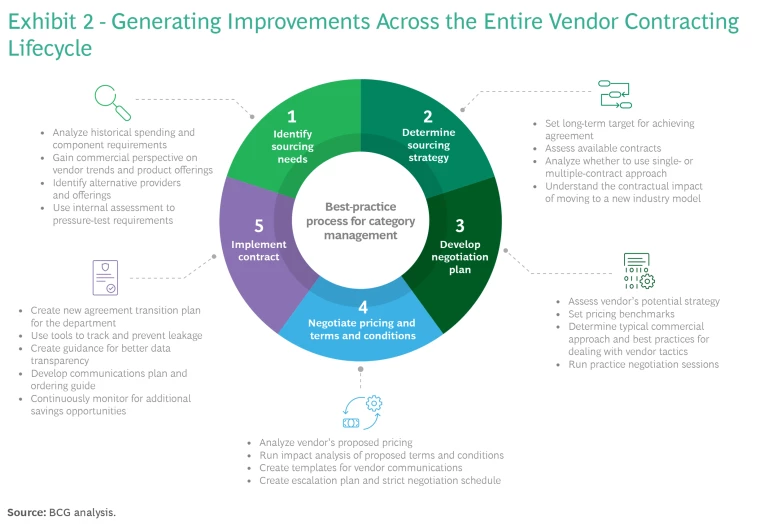

Attack the entire category management process. The savings above can be further driven home by improving the rest of the category management process. (See Exhibit 2.) As mentioned earlier, negotiations are only one tool at a leader’s disposal. For example, while identifying IT needs, leaders can challenge internal demand and push back against the assumption that historic levels are reflective of true requirements.

In addition, when determining their ultimate sourcing strategy, leaders should resist the status quo and assess whether alternative options, such as different contract mechanisms and bundling or unbundling requirements, can create savings.

Leaders should resist the status quo and assess whether alternative options can create savings.

Finally, when implementing a contract after negotiations, leaders should ensure that they continue to look for opportunities to save throughout the entire contracting process, including tracking and preventing leakage off the improved agreements that have been established.

Address underlying issues. Just as high-performance applications require proper computing infrastructure, high-performance cost reduction efforts require the right organizational infrastructure. Contracting policies should be improved, for example, to ensure that they do not create additional complexity for vendors. Key utilization data should be accurately measured and easily available during procurement decisions; for example, through internal knowledge management systems that ensure that IT and procurement organizations have access to the same consumption data. And vendor profiles should be clearly understood, including their business models, margins, strategic aims, and sales team compensation plans and incentives.

For example, when negotiating with cloud IaaS providers, which are more concerned about peak loads than total loads, government IT buyers can win overall discounts by locking in non-peak computing rates. Similarly, a government buyer that understands its vendor’s sales compensation structure might be able to achieve discounts by timing purchases to align with a vendor’s bonus accelerator schedule.

Once a more optimal organizational infrastructure is in place, CIOs can create savings more effectively. With improved contract management, for example, they can encourage the use of standard terms and conditions that reflect best practices and regularly assess contract performance to ensure that vendors are meeting expected service levels. They can deploy accurate utilization data to reduce quantities or service levels without harming the mission. And they can use their knowledge of vendor incentives to improve the negotiation process.

Have a plan to recoup and reinvest savings. Government CIOs need to understand their current IT costs and where cost reductions will occur so that they can track program progress and ensure that the expected reductions are delivered. The current cost baseline should therefore accurately reflect all spending controlled by the CIO and include estimated shadow IT spending to the extent possible. Without a clear baseline and tracking, the CIO will not be able to hold the agency accountable to its cost-reduction strategy.

Agencies also need to understand and control where funding will go once cost reductions are achieved; that is, the budgets that will benefit from the effort. CIOs should therefore proactively define their strategy for recouping IT cost reductions and track the results. Otherwise, cost-reduction efforts may unintentionally flow funds to lower-priority or unnecessary projects in a different area of the organization, negating the cost reduction and boosting inefficiencies elsewhere.

Manage the Changes

All these efforts to lay the groundwork for savings will be for nought if agency CIOs are unable to push through on the toughest decisions, gain the support of internal stakeholders, and follow through to keep the momentum going. Below are two examples of actions that government leaders have taken to ensure that their efforts create meaningful and lasting change.

Accept the need for tough decisions. When commercial organizations cut costs, they know that reorganization and outsourcing (i.e., headcount reduction) are always options, even if they are not to be undertaken lightly. Government CIOs need to have a similar level of intensity if they are to lock in deep, significant savings. They must be willing to accept the pain that comes from telling people “no” and pushing back on requirements. And they must be prepared to take the following steps where appropriate:

- Stop programs or cease investments.

- Force IT standardization (for example, of devices and software).

- Limit features to those necessary.

- Negotiate hard with suppliers.

- Eliminate unneeded contract jobs.

- Reorganize long-held roles and responsibilities.

- Centralize funding.

The opposition will be tough, as those affected will say the current investments are critical, their missions are unique, they need more functionality, and they won’t budge on pricing, among other arguments. Each of these responses should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and not taken as automatically exempting a program from cost containment.

Frame the benefits to motivate internal stakeholders. Cutting costs can be a difficult pill to swallow in an organization not motivated by optimizing its profit and loss statement. To achieve buy-in, CIOs should present their efforts in a mission-centric way, such as by saying that they are using the funds to reinvest in agency priorities. If members of the leadership are asking their internal stakeholders to sacrifice, they must communicate the longer-term benefits clearly.

Once the changes are made, agencies must refrain from falling back into habitual practices. We recommend that CIOs keep four questions top of mind:

- How can we institutionalize new cost-saving practices and processes?

- What written policies and procedures should we update to support long-term savings?

- How can we track and show the impact our efforts have had?

- Who else should buy into the changes to ensure that they last?

With these answers in hand, agencies can work toward enduring cost management success.