When interest rates rise, innovation budgets often fall. Yet preserving cash and fostering innovation are not mutually exclusive strategies. On the contrary, companies should embrace innovation even in challenging times. This principle held true during the Great Depression and in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, as innovative companies thrived and outperformed their peers in both the short and the long term.

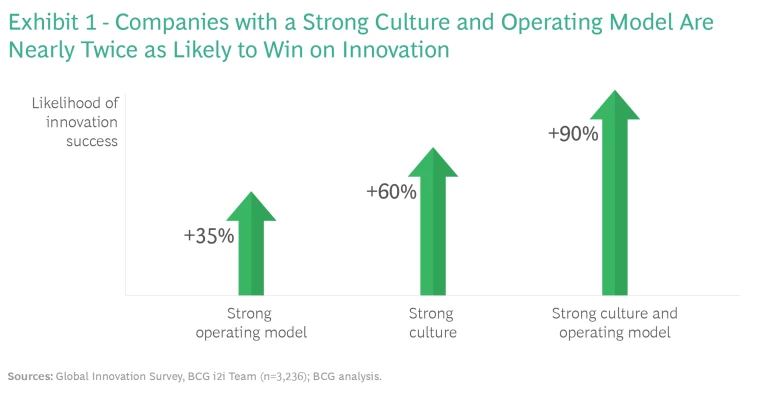

Encouragingly, 86% of corporate innovation heads agree. As our Most Innovative Companies 2023 report reveals, leading companies have either maintained or substantially increased their investment in innovation this year. To reap the full benefits, however, companies need to promote a culture of innovation. Our research and survey results consistently show that companies with an innovation culture—those that embrace risk, foster collaboration, and grant autonomy to their teams—are 60% more likely to be innovation leaders.

In this article, we present some practical guidelines for executives seeking to design a high-impact innovation culture. And we outline four areas of focus that offer a clear path for change, drawing on examples from leading innovators.

Culture, Innovation, and the Operating Model

First, what is culture? Essentially, it’s the way people interact in an organization and the way work gets done. Culture is organic; it is as much shaped by the present as it is influenced by the organization’s institutional memory and past behaviors.

An innovation culture is thus the collective behavior that shapes how new products and services get built and marketed to customers. To use an analogy, innovation culture is like software that runs on the “hardware” we generally associate with innovation: the strategies, governance, processes, organizational structures, metrics, and other aspects of the operating model.

All too often, we see a tendency to focus solely on the hardware of innovation. That’s only natural, as organization structure, processes, and metrics are part of the standard tools of management. They are the tangibles that leaders can readily see, analyze, and implement.

Alas, this focus comes at the expense of the software—and this fundamental misunderstanding can trip companies up. (See “Why Companies Get Stuck.”) Instead, hardware and software need to be seen as integral and foundational to innovation systems that drive real impact.

Why Companies Get Stuck

Other companies cling to the “not invented here” mindset, an insular view that sees innovation in terms of proprietary technology and eschews externally developed ideas or resources. They think innovation happens only in the laboratory—and as a result they make no attempt to adopt new ways of working (such as an open-innovation approach that fosters diversity of thought, idea generation, and experimentation). Still others conceive of innovation as an innately risky activity that requires “permission”—one that depends on extensive business-case development, formalized stage-gate processes, and heavy-handed stakeholder management.

Leaders who overengineer with endless stage gates are like helicopter parents who hover over their children without allowing them the unstructured, unsupervised play so essential to creativity and cognitive development. Their intentions are good, of course, but by focusing only on the “hardware” part of the picture, they end up creating a culture (a “software”) that does not foster the desired innovation outcomes. Both the software and the hardware are instrumental and must be in synch for the whole to work.

It’s the combination of a strong innovation culture and a lean operating model that makes a difference. As we’ve mentioned, companies with strong innovation cultures are 60% more likely to be innovators, while those with strong mechanisms in place (the hardware) are 35% more likely to be innovators. Those with both—we call them innovation culture leaders—are nearly twice as likely to be a world class innovator. (See Exhibit 1.)

Interestingly, innovation-culture leaders employ, on average, 10% fewer full-time people with formal innovation roles. What does this tell us? That culture does not have to be a costly endeavor—in fact, it can be a lever to run leaner, faster processes.

So how do you ingrain a culture of innovation? By changing the context in which people operate.

What Innovation-Culture Exemplars Focus On

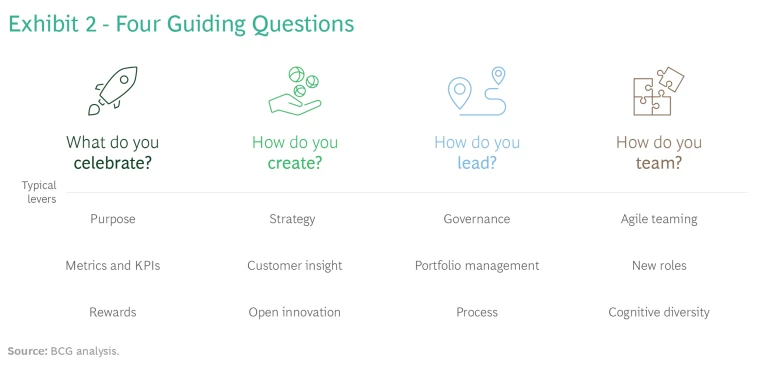

From our experience, we’ve identified four aspects of innovation culture on which companies often focus: what successes you celebrate, how you create, how you lead, and how you team. Importantly, these aspects either add—or destroy—value, depending on how your teams work together.

Each aspect, when framed as a question, can help you determine what route to pursue to bolster your company’s innovation culture. Zero in on one that offers the best opportunity for improvement and impact. (See Exhibit 2.)

Of course, culture change doesn’t take hold overnight. But we’ve seen companies effect change fairly quickly. Every company has a different starting point and selects different aspects of their innovation culture to focus on, depending on that starting point and their strategy.

Fundamentally, though—and it bears repeating—to change culture, a company must build it into the operating model from the beginning. Fortunately, many such tactics are easy to implement, and quick wins invariably have a snowball effect.

What do you celebrate? What R&D and innovation outcomes does your company reward? What actions put the innovation team on the company’s radar? What behaviors accelerate team members’ promotions?

One example of a company that strongly believes in creating an environment conducive to innovation—and that encourages creativity and idea development from everyone, not just its official R&D team members—is 3M. The Minneapolis-based company hit a milestone in 2014, when it was granted its 100,000th patent; it remains a serial innovator, averaging 3,000 new patents each year. Indeed, some of 3M’s greatest successes over the decades have come from experiments that didn’t pan out but were given new life (such as Post-Its, which were discovered in the search for strong adhesives).

The company has long understood that one of the biggest impediments to innovation is the lack of time and space for employees to think beyond their current tasks. Another is the lack of a central hub where employees can share knowledge and jointly develop ideas. Performance management systems that do not recognize initiative, knowledge sharing, and achievements are a third obstacle.

To innovate, employees need time and space to think beyond their current tasks.

Each of these impediments is relatively easy to address, however, and can yield quick results when redesigned in a way such that innovation-fostering behaviors are embedded into the company’s operating system.

The “15% rule,” which 3M has formalized, is one easy-to-implement policy. It gives employees the right to spend 15% of their time (also known as “magic time”) on side projects. (Post-Its, in fact, were invented on one employee’s 15% time.) At the company’s Tech Forum—an informal organization similar to a university society—people can join a team to collaborate on a side project. Mentoring, teaching, and time spent developing others all count in formal performance reviews; in fact, they are requirements not only for promotion and incentives, but for advancement to the “Carlton Society,” the company’s highest technical career level.

3M understood earlier than most companies that it had to create a “pull” for innovation throughout the organization. While 3M rewards technical breakthroughs, the company steers its innovation efforts in part based on product vitality. These innovation efforts are succeeding: while 3M is best known for products such as Scotch tape, Post-Its, and Thinsulate, one-third of its sales come from products invented within the past five years. Purposeful choices like this—to reward innovation that promises to have impact rather than innovation for its own sake—have made 3M a serial innovator.

How do you create? How do you get new ideas? Do you introspect or interact with people outside of your company? What role do customer insights play in idea development?

Consider Unilever. The Foods R&D center of the consumer products giant was, until not long ago, located on the outskirts of Rotterdam, far removed from external influences and sources of inspiration. The company staffed its innovation teams almost exclusively with internal experts, which created a bottleneck when specific expertise was not available. It also slowed down innovation because highly qualified team members would get caught up in more transactional research activities. Finally, Unilever’s in-house-only development process meant that new ideas were often latecomers to a trend.

To unlock an innovation culture with impact, the company decided to create an open innovation ecosystem. Step one was relocating the R&D group to an innovation hub on the campus of Wageningen University, Europe’s foremost center for food and agricultural sciences research. The new location made it easier for the team to access a research network and cultivate partnerships.

Companies that build innovation ecosystems can achieve better—and faster—results than companies that rely solely on in-house R&D.

Unilever augmented its in-house expertise with research contracts and joint initiatives with other local universities for more transactional work and new technologies such as high-throughput robotics and digital modeling capabilities. In this way, it expanded its access to talent while reducing its cost base. This model was replicated in the company’s home and personal care unit with the creation of the Materials Innovation Factory at the University of Liverpool—today one of the largest centers for high-throughput robotics in material science.

One quick win Unilever scored was instituting a new approach to intellectual property (IP) rights. The company gained arising IP rights for its core categories only, agreeing to cede the rights to a project partner if it didn’t use the result of the research within two years. This policy helped the team shift to an outward-looking culture while making partnering with the company even more attractive to external parties. Unilever also added digital skills to the job requirements for new hires, so that team members could work competently with the digital R&D model the company had adopted to speed collaboration and idea development.

How do you lead? Who makes what decisions on innovation? How broad are your project leaders’ decision rights? Do you as a company lead by authority, or is leadership an activity anyone can participate in?

Take EDP (Energias de Portugal), a global green utility headquartered in Lisbon. Initially, the company’s innovation model revolved around open innovation, an approach that relied predominantly on collaborations with startups through joint pilot projects and commercial contracts. This strategy produced the WindFloat project, a major success for EDP. The project developed an innovative technology that enables the company to explore wind potential at sea, at depths greater than 40 meters, without the need for towers.

To achieve a similar impact with even more projects—while better managing the significant risk inherent to any transformational innovation—EDP launched Innovation 2.0, a new approach to innovation that would also allow the company to replicate such success more systematically.

As part of Innovation 2.0, EDP unveiled the “Spiral” program, which had two objectives: spurring transformative ideas from those closest to the business needs and instilling a culture of innovation leadership among the company’s up-and-coming talent.

By empowering teams to pursue projects that have significant commercial potential, companies can de-risk the crucial early stages of innovation.

It took many months for EDP to strike the right balance between empowering the teams while providing them with direction. An initial flurry of more than six dozen ideas was whittled down to the most promising ten. EDP arrived at a streamlined approach to vetting ideas, centered around four pivotal questions: Is the problem to be solved for significant? Can solving it have commercial impact? Is the innovation feasible? And can EDP succeed with it?

To this end, leaders crafted open-ended prompts, such as “How might we reduce energy losses from complex interference processes (the ‘wake effect’) in a wind park”? And they encouraged teams to think “problem first, and then solution” instead of starting with technology. The top ideas are now being developed, guided by project mentors, and funded with ad hoc, stage-gate budgets before the innovation board unlocks more significant development budgets.

This approach has created a culture of innovation at EDP that seeks to de-risk big ideas as early as possible, showing that precision guidance, empowerment, and ownership can lead to more projects that promise transformative impact.

How do you team? Do you enable everyone in your company to participate meaningfully in innovation? Do you draw on the most diverse perspectives when you form teams, or not?

At the dawn of the 2010s, Rakuten, the Japanese e-commerce company, was “lost in translation,” literally losing days of work while translating documents between English and Japanese. Such slowdowns were putting the company at risk of losing its innovation edge. So one day, CEO and founder Mickey Mikitani instituted a bold new requirement: he declared that all company communications, from meetings and presentations to the canteen menus, would be in English. Mikitani gave employees two years to learn the language, offering free classes, e-learning tools, and one-on-one support. Employees who achieved the goal were eligible for promotion; those that did not risked demotion.

Innovation requires collaboration--which means removing the barriers to communication within a company.

Understandably, the transition was stressful for many employees. But the “one common language” requirement transformed the company’s innovation culture. Not only did it remove the language barrier that had impeded employee communication and prevented collaboration with global colleagues, but it allowed the company greater access to global talent.

At Rakuten’s corporate office today, there are employees who have migrated from Bulgaria, France, Indonesia, Germany, Iran, and elsewhere, and 80% of its new engineers hail from countries other than Japan—a total of 70 different nations in all. Thanks to this simple way of building a more collaborative work environment, Rakuten is now seen by many as an exemplar of the modern, digital, global Japan.

How to Rev Up Your Innovation Culture

These four examples offer inspiration to companies whose innovation culture needs a reset. But they represent merely a handful of ways in which culture leaders have fostered, pivoted, and sustained vibrant innovation cultures.

How can you build an innovation culture that will support your strategy? Start by looking at three things all culture leaders do well:

- They clearly articulate the specific behaviors that are most critical to their innovation success. Among them: striking a balance between freedom and accountability; encouraging risk taking; and fostering playfulness while adhering to company standards. Companies that take their innovation culture seriously are crystal-clear about how these behaviors are defined: “freedom,” for example, means seeking input, not consensus, while empowering decision making; “encouraging risk taking” means telling teams to dream big, learn from failure, and improve continuously. Companies that lead in innovation culture make sure to cultivate and reward those behaviors.

- They activate these behaviors through the actions of their leaders. An innovation culture is shaped from the top. Leaders articulate an innovation vision for their company and personally engage in key ecosystem outreach activities. They inspire innovation by providing the needed hardware to support the software: the incentives, platforms, and mechanisms for celebrating, cultivating, and rewarding new ideas; the accountability and ownership that teams need to operate unencumbered; and the freedom to collaborate with external partners. Put simply: leaders—from the C suite to the front line—“walk the talk.”

- Most importantly, they embed the core behaviors into their operating model. Innovation culture leaders know it takes more than setting up creative spaces with ping pong tables and espresso machines or laboratories segregated from the rest of the workforce and the company’s day-to-day currents. Culture runs deep: it’s embedded in a company’s incentive systems, policies, processes, and practices. These companies also foster a strong innovation culture in their very hiring practices, seeking new employees that have an innovation mindset as well as those with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and ways of thinking.

An Innovation Culture Barometer

Articulate

- How well have you identified the focused set of behaviors that your organization needs to spur innovation and support your strategy?

- How specifically and actionably have you articulated them?

- How well do they serve as a guide for what “great” looks like in employees’ and leaders’ daily work?

- How effectively are your company’s leaders role-modeling and supporting these innovation-fostering behaviors and activities?

- What could they be doing differently to become more effective role models? Are there any visible, symbolic moves that they could make immediately?

- What support might they need in order to get started, and to stay the course over the long haul?

- Which of your company’s operating model elements might currently be quashing important innovation-fostering behaviors?

- What are the two or three changes you could make to your operating model that would best “hardwire” these behaviors?

Not long ago, Harvard Business School professor Gary Pisano observed that innovation leaders “have a tolerance for failure—but an intolerance for incompetence.”

By focusing intently on these three areas—articulating, activating, and embedding the right behaviors—you’ll be able to establish the best possible conditions for creating, teaming, leading, and celebrating innovation. Doing so thoughtfully and consistently will spark the innovation culture your company needs. Indeed, you’ll be surprised by how quickly results accrue and sustain.